There are compelling grounds for fearing that Russia’s restoration work on the world-renowned Khan’s Palace in Bakhchysarai could forever destroy this vital monument of Crimean Tatar cultural heritage. While Russia denies the accusations, photos smuggled off the site are alarming, as are the construction company’s and architectural firm’s lack of experience in restoration work.

There are compelling grounds for fearing that Russia’s restoration work on the world-renowned Khan’s Palace in Bakhchysarai could forever destroy this vital monument of Crimean Tatar cultural heritage. While Russia denies the accusations, photos smuggled off the site are alarming, as are the construction company’s and architectural firm’s lack of experience in restoration work.

The Khan’s Palace in Bakhchysarai was placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage Tentative List in 2003, but the follow-up work for establishing its international status remains unfinished. According to Edem Dudakov, the former head of the Crimean Committee on Inter-Ethnic Relations and Deported Peoples, if the work now underway continues, the complex which includes the palace itself, a hall for receiving visitors, two mosques, a harem, and other buildings, will lose any chance of gaining UNESCO recognition in the future.

The wanton destruction of the site should be considered a major attack by an occupying force on a monument of considerable historical and cultural importance for Crimean Tatars and Ukraine. The complex was built as the main residence for the monarchs of the Crimean Khanate—the state of the Crimean Tatar people—and was the political, religious, and cultural center of the Crimean Tatar community until the collapse of the Khanate in 1783.

Restoration work on any building of historical significance needs to be carried out by specialists who attempt to use the same materials and technology of the period as possible. Instead, the work has been passed to a construction firm called Kiramet, working for the Moscow-based Atta Group Architectural and Planning Holding, as the general contractor. We can only speculate on the motives behind the selection of these companies, but relevant experience was certainly not a factor. The design has been kept secret, and there is no information as to whether a mandatory expert assessment was carried out. What is clear is that the workers are in a big hurry.

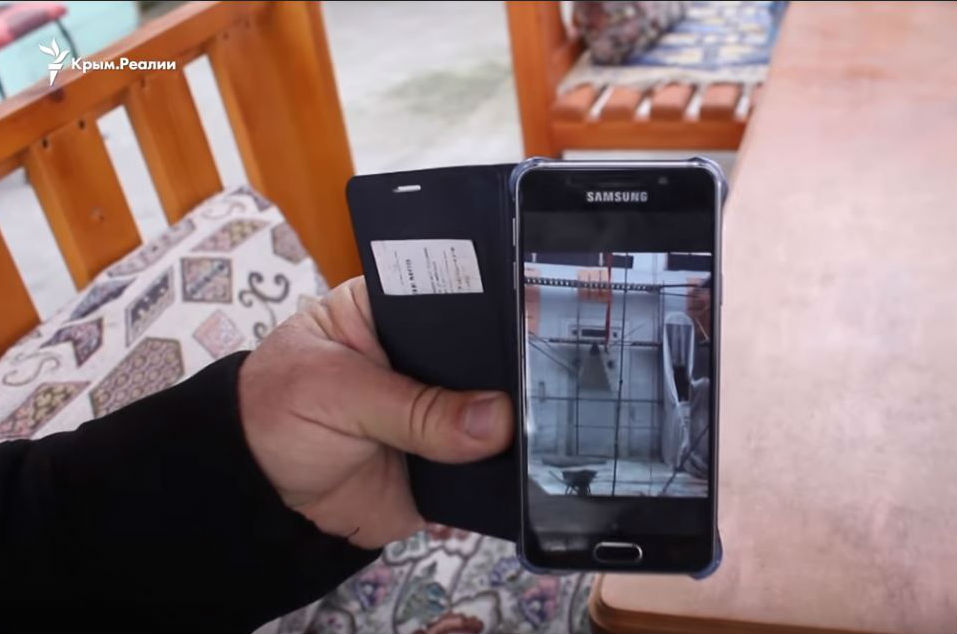

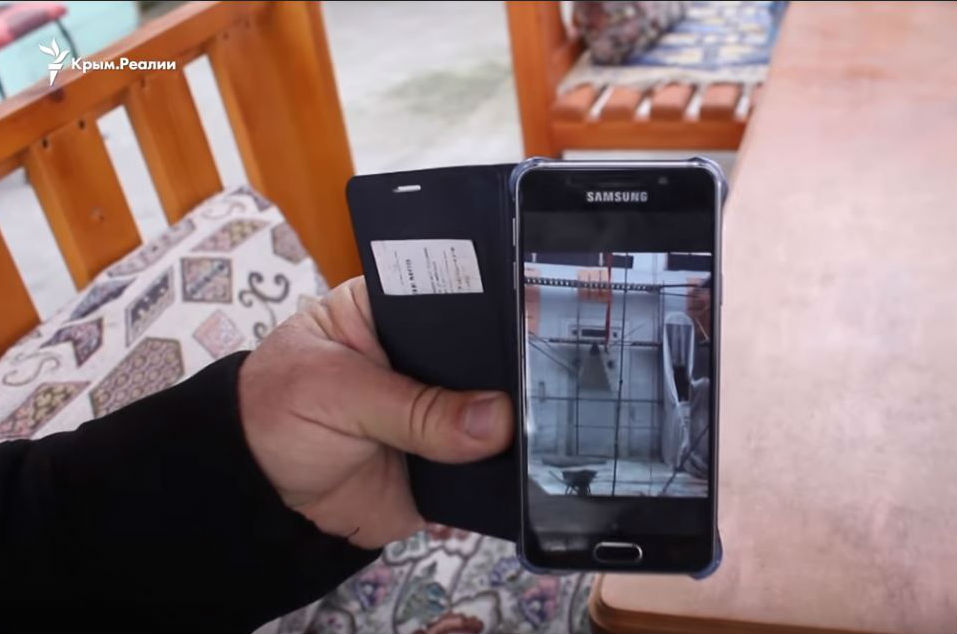

Although the complex has been closed to the public, people have managed to get through and take photos. Even without seeing the design, some parts of the renovation are clear. For example, the original tiles are to be removed and replaced with old-style Spanish tiles. Experts condemn this as deliberate destruction of the palace’s authentic nature. Each missing tile, they insist, should be made by hand, using the original technology.

RFE/RL’s news website Krym Realii has spoken with Elmira Ablyalimova, the former head of the Bakhchysarai Historical, Cultural, and Archaeological Museum-Reserve, who is appalled by what she sees in photographs of the construction site. She notes, for example, how parts of the sixteenth-century walls under the roof of a mosque have been broken off while stones from the period are left lying around as if they’re rubbish. She calls what is taking place a crime.

A heavy metallic shell is reportedly being built around the main body of the palace, with plans to cover it with a canopy roof. Experts warn that the ground may not withstand the weight of this construction and could sink. They also point out that workers have not put up any proper protection for gravestones and the calligraphy painted on some walls. Most incredibly, three hundred-year-old beams appear to have been cut down and the wooden fortification simply covered in concrete. This is clearly not a restoration, but the foundation of new construction.

Ukraine should raise the current status of the monument from one of local significance to one of national importance, so as to draw greater attention to this act of shocking vandalism, Dudakov believes. The problem, however, is that Ukraine’s voice will simply be ignored, unless the international community gets involved. Intervention is urgently needed, since each day brings new, irreparable damage.

Well-known Crimean Tatar rights lawyer Emil Kurbedinov announced that his team of lawyers were planning a legal battle to protect the Khan’s Palace from an “unjustified attack on the historical heritage of the Crimean Tatars.” He did not wish to reveal all the measures they are planning, but said they would first seek official answers from the Russian Federation before turning to international bodies, including UNESCO. The lawyers will seek to ascertain where the dismantled materials are being taken, and who initiated and agreed to the dismantling.

Kurbedinov noted the obvious hypocrisy if one compared this situation with the excuses given for expelling the Mejlis, the representative assembly of the Crimean Tatars, from the building they had always occupied in Simferopol. Initially, several rather vague pretexts were given in 2014 for ordering the Mejlis to vacate the building within twenty-four hours; however, the occupying Russian regime used the fact that air conditioners had been installed and some cosmetic repairs carried out to claim that the Mejlis violated standards for a historical monument. Now work that is anything but cosmetic is being carried out by the Russian occupiers with no regard to historical preservation.

Halya Coynash is a member of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, which originally published this article. The story has been edited for clarity and published with permission.

Image: The Khan’s Palace in Bakhchysarai, Crimea, has been closed and is being renovated. The plans have not been released. A photo shows the renovation work, which Crimean Tatar groups and experts condemn. Credit: Courtesy screenshot Krym Realii/Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty