When thousands of Ukrainian citizens and most journalists fled to safety, Stanislav Aseev, an aspiring young journalist from the Donbas decided to stay put. Surrounded by frequent shelling, rupturing grenades, flying rockets, worn by the psychological stress of death, destruction, and high unemployment, and bombarded by propaganda that shattered friendships and families, he put his life on the line to tell this story.

When thousands of Ukrainian citizens and most journalists fled to safety, Stanislav Aseev, an aspiring young journalist from the Donbas decided to stay put. Surrounded by frequent shelling, rupturing grenades, flying rockets, worn by the psychological stress of death, destruction, and high unemployment, and bombarded by propaganda that shattered friendships and families, he put his life on the line to tell this story.

Aseev paid a high price. In June 2017, the separatists arrested him on trumped-up charges of espionage, tortured him, and refused to include him in the last big prisoner swap.

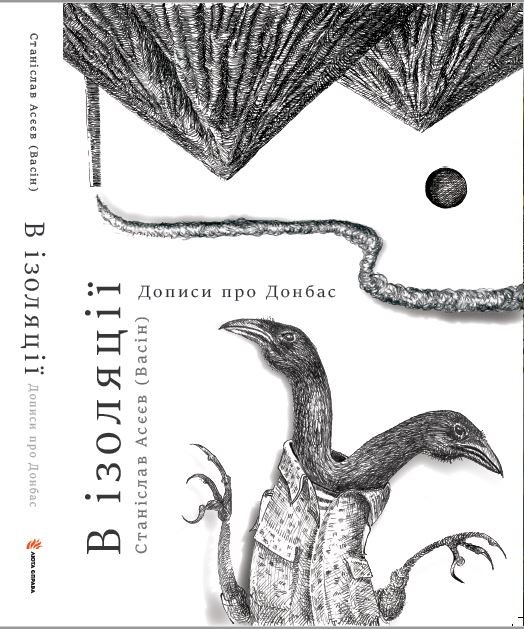

To mark a year of his imprisonment and remind the world of the danger of reporting where freedom of speech doesn’t exist, Radio Svoboda published In Isolation, a collection of his articles that cover events between 2014 and 2017. The title is a play on words: it refers to the condition of occupied Ukraine and to the former factory now used as a harsh prison where Aseev is being held.

The book is a vivid description of the occupation: from the lively downtown of Donetsk to the dark alleys of Luhansk to other depressing and neglected towns resembling one big military base.

Book illustration by Serhiy Zaharov, artist and former captive of “Isolation” prison in Donetsk where Stanislav Aseev is now being held.

In Aseev’s account, the majority in the Donbas, whose popular support made the republics possible, is working class with a deeply rooted Soviet mentality. These people yearn for a strong hand, fear change, ignore democratic values, and tolerate injustice. They’re convinced that they don’t decide anything and prefer to delegate responsibility to a higher official whom they view as sacred rather than a public servant. The fatigue from working long hours at low wages has made them indifferent and cynical to everything, and the war has erased sensitivity to human grief. Although they are disillusioned with the unrealized nirvana of Novorossiya (new Russia), this doesn’t imply a love for Ukraine.

The current war is with the Soviet past, and “the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) is only a mirror of that past,” Aseev argues. This past is associated with personal memories that are hard to let go. For instance, Lenin is perceived not as a tyrant, but a memory of “a 28-kopeyka ice-cream and a warm family May parade in 1979.”

Aseev shows how this mentality makes them vulnerable to Kremlin propaganda. The myths about crucified children, the fear of Ukrainian Nazis, and worry over the dismantlement of a Lenin statue is foremost in their mind and prevents any rational argument.

He contends that Ukraine cannot win hearts and minds by force when nostalgia for the Soviet past reigns and few people support the Ukrainian government. And the longer the war lasts, the more difficult it will be to reintegrate the Donbas where the old generation cherishes portraits of Stalin and Putin, and the new generation is nurtured to hate and fight everything Ukrainian.

These chaotic separatist moods led to the loss of identity. He says that the majority aren’t sure whether they’re “republicans,” Russians or new Russians, but they know that they don’t want to be Ukrainians.

But a minority, Aseev among them, with pro-Ukrainian views, are forced to live in the shadows. They’re considered enemies in the DPR but forgotten in Ukraine. On his trips out of the war zone, he notices that Ukrainians regard the Donbas as a ghost region. Clearly it’s not; hundreds of thousands of Donbas residents crisscross the demarcation line to collect pension and buy products in Ukraine every month.

Though he despises the separatists, he pulls no punches in calling out the government for surrendering Crimea without a fight; abandoning administration buildings in Donetsk and Luhansk to avoid panic; shifting the blame for domestic problems on the foreign enemy; repeating that there is no alternative to the Minsk Agreement; and not clarifying the legal status for Ukrainians in the occupied territories.

He believes that when the virus of the “Russian World” burns out, reintegration will be possible through a dialogue initiated by people like him who stayed through the war, because the majority will never listen to outsiders.

He concludes that Ukraine can be saved through forgiveness by both sides. “Why not forget what’s western and what’s from Donetsk and start living anew…in a country whole and united?”

Aseev has unique credentials to analyze the war and finely sketch the psychology of the Donbas. Now in a rotting prison, he’s embarked on a hunger strike to protest ill-treatment. Many international organizations have called for his immediate release, but all efforts so far have been unsuccessful. More Western pressure is needed.

Vera Zimmerman, a UkraineAlert contributor, is an independent research analyst and translator. Here Zimmerman reviews Stanislav Aseev’s In Isolation: Notes on Donbas. Kyiv: Radio Svoboda, Luta Sprava: 2018, pp. 210, free, in Russian and Ukrainian.

Image: A worker sits in a vehicle at a coke plant in the town of Avdiivka near Donetsk, eastern Ukraine, June 23, 2015. REUTERS/Gleb Garanich