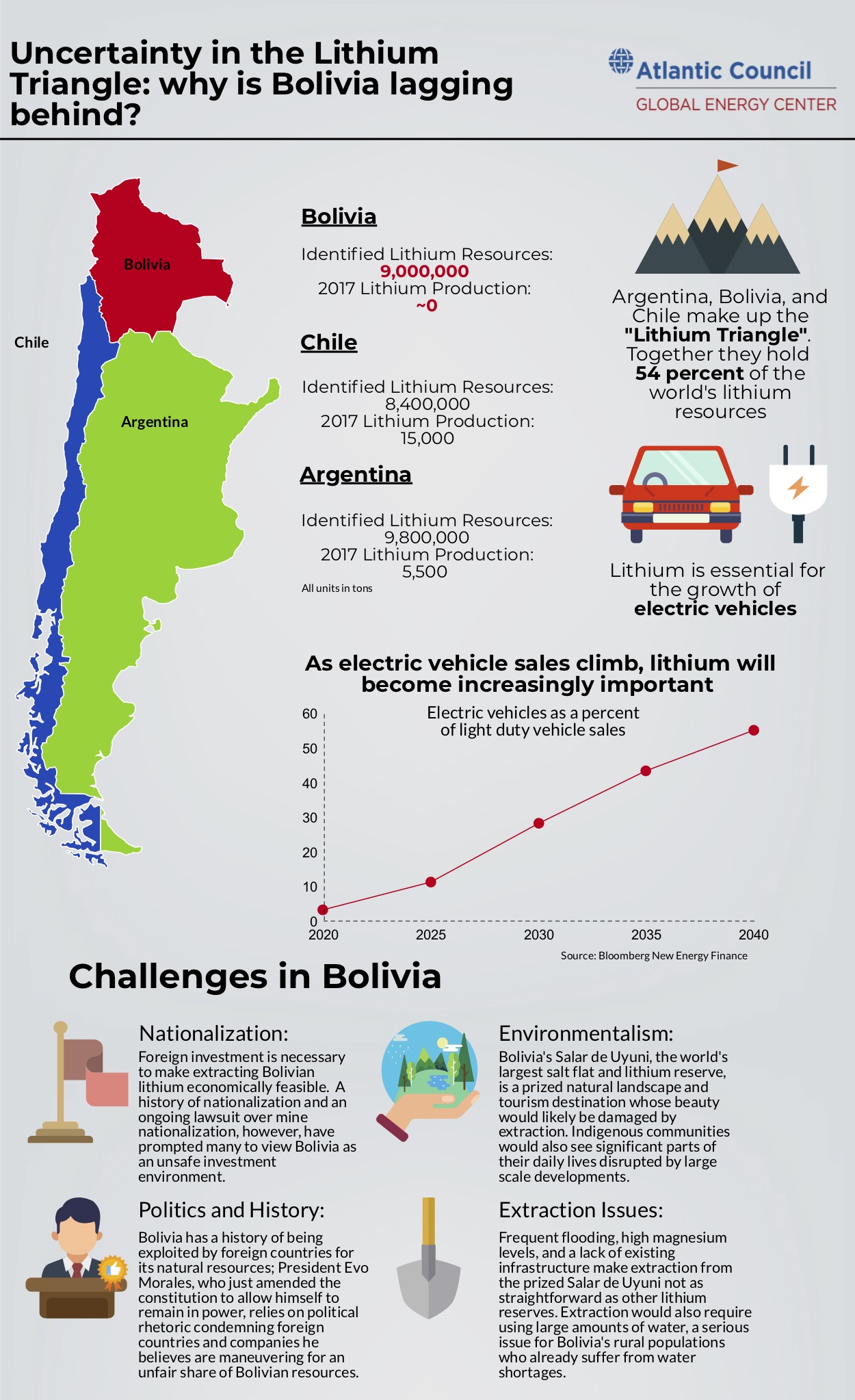

Electric vehicles (EVs) will play a central role in any potential global transition away from hydrocarbons and towards a more sustainable energy future. Projections of EV growth are widely bullish: by 2040, Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects 55 percent of new car sales and 33 percent of the global fleet will be EVs, while BP expects 30 percent of car kilometers to be covered by EVs. EV projections have been growing substantially in recent years, thanks in part to decreasing battery costs.

However, the materials needed for advanced EV batteries have come under close watch because of their rarity and geographic concentration. Lithium is one such material. In the wake of these bullish EV projections, automakers are scrambling to ensure adequate supplies of lithium, which is both limited and concentrated. In 2017, lithium production was confined to a small number of countries, with Argentina, Australia, and Chile accounting for over 85 percent of global production. Those same three countries also hold over 75 percent of the world’s proven lithium reserves.

When it comes to lithium resources, however, the picture is very different.

While reserves are proven and economically recoverable quantities of a given material, resources represent the total amount of that material that exists. Although Bolivia currently produces a negligible amount of lithium, the country holds over 25 percent of the world’s lithium resources. Thus, while it may not have yet have production, it has a high potential to be crucial for EV growth and a broader shift away from hydrocarbons.

For Bolivia, lithium’s potential is no small issue. With the lowest GDP per capita in South America, many there hope that lithium might provide desperately needed economic stimulus for the country. Some have even speculated that its resource potential, if realized, could help Bolivia become the “Saudi Arabia of Lithium.”

This prosperity, however, is not guaranteed. One of the most important constraints weighing on Bolivia’s planning process is historical experience. Bolivia once held South America’s second largest natural gas reserves, but they were exploited by foreign companies and governments to the detriment of the Bolivian population, especially Bolivia’s large indigenous population (over 40 percent of the total population). Evo Morales, Bolivia’s current president, is the first indigenous president in the country’s history, frequently espousing anti-American sentiment to rally support for his far left populist platform.

While lithium production does have great upside, there are several obstacles impeding production of Bolivia’s plentiful resources. Because its lithium resources are not as easily accessible as those in neighboring Chile and Argentina, Bolivia will need foreign investment. The primary source of Bolivian lithium is Salar de Uyuni, a vast salt flat which is a key tourism destination and source of pride for the local population. Estimates of the flat’s lithium resources vary, with some estimates putting it at more than one quarter of the world’s lithium deposits. Extraction from the Salar de Uyuni, however, is inhibited by frequent rains and high magnesium levels, meaning that foreign companies with capital and advanced technology will be needed to devise a solution.

Significant production would also mean detracting from the pristine state of the salt flats and disruptions for the surrounding area’s population. Extraction would likely require a large amount of water, a notably precious resource given Bolivia’s existing water supply problems—in 2000, there was even a brief “Water War” in Bolivia. Politically, Morales fashions himself a champion of Bolivia’s rural and indigenous populations, exacerbating water supply problems while tarnishing a source of national pride and cooperating with foreign companies could be greeted with skepticism—or even hostility—by Morales’ base.

Furthermore, while Bolivia may need foreign investment, that does not mean Morales is eager to strike deals. A wariness based on historical experience is likely behind Morales’ skepticism and fear that Bolivia’s lithium could be preyed upon by foreign companies, denying the Bolivian people the chance to benefit from the profits. To prevent exploitation, Morales envisions Bolivia as a location not only for lithium extraction, but also for battery and vehicle manufacturing. If successful, entire production chains would be developed in Bolivia, facilitating more widespread economic development. However, some of the foreign companies and expertise Bolivia needs to effectively extract its lithium do not share this vision.

The largest inhibitor of foreign investment is Bolivia’s reputation as an unsafe investment climate. After assuming office in 2006, Morales nationalized Bolivia’s hydrocarbon industry, stripping ownership from foreign companies and delivering on a campaign promise to address Bolivia’s severe inequality. Glencore, a Swiss mining company which had a number of mines in Bolivia, took legal action in 2016 against Morales’ government after some of its mines were seized.

Against this backdrop, many investors are cautious of whether substantial investment would be safe once production began despite Morales’ declared willingness to start the process of foreign investment for lithium production. In addition to qualms about Morales’ ideology, there is his grip on power: Morales has defied a failed public referendum to allow him to amend the constitutional term limit, declaring his candidacy for next year’s election despite already reaching the constitutionally decreed term limit. Morales previously launched a legal battle in 2013 to allow him to run for a third term by arguing that his first term, which began in 2006, did not count as a full term because Bolivia adopted a new constitution in 2009.

Despite the issues, some firms are taking the risk and embracing the opportunity to invest in Bolivian lithium. This April, Bolivia reached a major deal with German company ACI Systems to manufacture and market lithium batteries in Bolivia. ACI Systems will invest $1.3 billion in the project, and the Bolivian government will retain a majority share. Bolivia also signed a preferential trade agreement with India just weeks ago, pledging to make its lithium available to India, which has high ambitions for its domestic EV fleet.

This is likely only the beginning of a much longer story about Bolivia, lithium, and energy shifts. As EV supply chains assume a more important role in the global economy, lithium may become a prevalent geopolitical issue. China already has significant domestic production and has purchased a large share in Chile’s largest lithium company, consolidating some control over lithium supply. It is plausible that even as the world begins to move away from oil and gas as dominant geopolitical issues, materials of newfound importance, including lithium, could grow to be similarly contentious. If so, countries like Bolivia may experience previously unexpected political and economic booms, serving the crucial role of satisfying the world’s demand for environmentally friendly technologies.

Herbert Crowther is an intern at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.