Watch and learn more about the event

Event transcript

FREDERICK KEMPE: Hello, I’m Fred Kempe, president and CEO of the Atlantic Council, and welcome to our viewers from around the globe. We are delighted today to have Hillary Rodham Clinton, former secretary of state of the United States, for all of our global viewers.

Secretary Clinton’s been responsible for many breakthroughs, many first in her life. She was the first woman to be the presidential candidate of a major US political party. She is one of only three women who have served as secretary of state. She was the first lady. She’s been a US senator. And so we’re delighted that she’s also going to have another first with us: She is going to be the first speaker in our brand-new series Elections 2020: America’s Role in the World, Powered by Samsung.

This is also at the same time part of the Atlantic Council Front Page Series. This is our premier live ideas platform for global leaders. We’ve had heads of state and government of Colombia, of Afghanistan, of Venezuela… and Singapore. We’ve had the head of NATO, the secretary general of NATO, and the executive director of the IMF. So we’re delighted to add former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Between now and November, we will feature the most prominent voices shaping the international dialogue to explore questions regarding US leadership and interests in the world, alongside our friends and allies. And that’s, of course, always the focus of the Atlantic Council.

Secretary Clinton knows that this is a time of geographic distance, but at the Atlantic Council we don’t believe so much in social distance. We have a huge audience across multiple digital platforms, and you can all comment about this event by using Atlantic Council Front Page hashtag #ACFrontPage.

So with that I want to turn to Secretary Clinton. Secretary Clinton, thanks so much for being with us to launch this important series. We’ve got—

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Thank you very much, Fred.

FREDERICK KEMPE: It’s wonderful to see you even though it’s against a screen and you’re somewhat distant from us here.

This is an historic moment and an unusual year. It’s the worst pandemic in a century, the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, the most significant racial upheavals in 50 years. And some are saying this may be the most important presidential election of our lifetimes.

I wonder if you can speak first to that. You know a lot about history. You’ve been a presidential candidate yourself. What are the stakes this year?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well, I agree with that assessment, Fred, that this is the most consequential presidential election in a very long time, and for all the reasons that you just pointed out, in addition to the challenges that we face, both domestically and internationally, in trying to chart a better, stronger approach toward the future, which I believe is at stake in this upcoming election.

Just very quickly, we’ve seen a real failure of leadership here at home and abroad by the current administration. We’ve seen real disregard for institutions such as NATO, but also institutions here at home; an undermining of the rule of law at home and the rules-based global order abroad. We’ve seen a failure to respond effectively to the pandemic. And, of course, there are many other challenges that have been either ignored or made worse in the last three and a half years.

So this is a moment of reckoning not only for the United States, but, as you rightly point out, the international community also has a lot at risk in the outcome of this next presidential election here.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So, moment of reckoning. If you look at the challenges for the next president of the United States, they’re going to be enormous. And always setting priorities is one of the hardest things to do in leadership. If you’re looking at the challenges you’ve outlined and the problems we’re facing internally domestically, and in the world, where do you set the priorities? If you’re setting priorities one through three, one through five, what are they?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well, it’s interesting, because I’ve had this conversation with the vice president, the vice president’s campaign, now increasingly with those in the transition effort that is underway. Because this is not an ordinary time, there will have to be a concerted effort to move on several fronts at once.

It reminds me a little bit of when then-President-elect Obama asked me to be secretary of state. And he said, look, our economy is in a terrible great recession, which, of course, it was back in 2008 and ’09. I have to deal with the economic crisis, but we also have problems around the world. We have neglected our leadership and our alliances in the prior eight years.

Well, I think you just have to quadruple that to understand what President-elect Biden might be facing. And so I think there has to be a full-court press, as we say, both on the economy at home, dealing with the aftermath of the pandemic, because I don’t think it will be over by the next inauguration; making sure that we have a strong response to people’s losing jobs, as well as health care, because in our country, as you know, health care is often attached to employment, something that we are trying to change.

And then abroad we’re going to have to quickly move to try to regain leadership and rebuild our alliances and make clear to our competitors and adversaries that, you know, the vacuum is no more, that the United States is going to resume a position of global leadership and bring people together around common threats, whether it be climate change or the global pandemic.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So as I said earlier, you were the third woman—after Madeleine Albright, Condoleezza Rice—to be secretary of state, the 67th secretary of state. Foreign policy usually doesn’t play as big of a role in presidential elections. And I wonder what role you think it will play this year—whether it will be any different because of the situation we’re in.

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well I think it should and I hope it will. We have some very serious challenges internationally. And I think the press and the public should be demanding answers from the incumbent, Donald Trump, and the challenger, Joe Biden. And I have a lot of confidence in Joe Biden’s experience on the international scene. I worked with him in the Senate for eight years. I worked with him in the Obama Cabinet for four.

So just take a quick look at what we face. We face this global pandemic. We’re going to eventually—I hope after only it’s proven safe and effective—have a vaccine or more than one vaccine. Then we’re going to have to figure out how, working together in a cooperative way, the world can distribute and deliver that vaccine globally so that we really do tame the virus.

We’re going to have to deal with the continuing interference in our election by Putin and the Kremlin. This is an ongoing threat to our own democracy, but also to other democracies, and it needs to be addressed firmly and finally rather than allowing it to fester, because we know from recent intelligence reports that the Russians are once again trying to favor and help elect Donald Trump.

We need to have a stable, consistent policy toward China, the most consequential of our global relationships. I don’t blame the Chinese for filling the vacuum left by the incoherent and inconsistent policies of the Trump administration, but we can’t permit China to dominate the Pacific region and beyond and try to substitute its own power and influence for a rules-based global order.

And there are many other issues, whether it be climate change or the renewed effort by Iran to get a nuclear weapon or the unchecked efforts by North Korea and so much else that we’re going to have to pay attention to.

So I hope that the incoming Biden-Harris administration will be prepared to move on a number of fronts, domestic and international, simultaneously, because the work is rather overwhelming that needs to be done.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you, Secretary Clinton. Because you’ve mentioned the Biden-Harris ticket, let’s deal with a couple of issues that have been in the news in the last few days that are quite a bit of importance.

As you said, Vice President Biden has named Senator Kamala Harris as his running mate. Vice-presidential choices are sometimes written off as not being all that important. Some people are saying it should be and will be more important this time for two reasons—many more as well—that she is a woman of color and Vice President Biden, if there were a second term, he were running for a second term, would be 81 years old. How important is this vice-presidential pick, do you think?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well, I think it’s important and it is significant. Having gone through this myself, I mean, you want to pick someone you believe can become president, if necessary; someone that you feel would be a good colleague that you can work with and can give increasing responsibility to, and someone, obviously, who can help you win. And the vice president concluded that Senator Harris checks all those boxes.

I think that her incredible energy, her experience, her story, life story, will be very compelling in this election. And having both campaigned with her and for her, I have seen first-hand how thoughtful and focused she can be.

So I think it’s an important and significant choice. I think that the country would be in very good hands with a Biden-Harris administration. And now, you know, we have 80-plus days to try to make sure that we have a free and fair election without foreign interference so that the maximum number of eligible Americans are able to vote, and their votes be counted, so that we are confident in the outcome of the election in November.

FREDERICK KEMPE: History has shown that an international event, like COVID-19—you really have to go back to the Spanish flu to think of something that consequential—can have huge geopolitical implications. You’ve talked a bit about how we should respond to it. But in a geopolitical sense where do you see the opportunity that could be seized, but also what’s the danger? Could this accelerate history in a way that many have said, which would actually accelerate the relative decline of the United States?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well, I think that’s really up to the United States. And that’s why this election is incredibly important in every way I can imagine. You’re right, Fred, about the history of pandemics—whether it be, you know, the Black Plague in the Middle Ages or the so-called Spanish flu 100 years ago. We’ve seen the failure of governments to deal with the pandemic. And that is a wake-up call for everyone to understand that we need to both take a hard look at public-health processes and institutions within countries, but also internationally.

I thought it was a grave error for Donald Trump to attack the World Health Organization, and to act as though he could pull the United States out of it, something that is more complicated than he lets on. We should be buttressing the World Health Organization. We should be buttressing Gavi, the vaccine institution that has been set up internationally. We should be having intense diplomatic conversations with health experts, logistics experts, and others about how we are going to finally get to a safe and effective vaccine, or perhaps even more than one, and then manage the distribution of it so that we try to bring the world together around defeating the pandemic, not permit the vaccine nationalism that is taking place right now.

So there’s a lot of really important work that needs to be done. And the United States has to be in the middle of it. It cannot sit on the sidelines being indifferent or even contemptuous of international efforts and expect that we’re going to benefit ourselves, as well as lead the world. Because a final point is, you know, we saw a virus jump from Wuhan, China to the United States, and Europe, and now literally the entire globe. And to think that we can, you know, shut ourselves off and pretend as though we can deal with it on our own is both scientifically and politically, and strategically I would say, false.

So I would wish that rather than the behavior we’re currently seeing from the Trump administration, we would see a more thoughtful, smart, engaged, cooperative effort. Because that’s what it’s going to take. It took that to eliminate smallpox. We’ve been working for decades to eliminate measles and polio. It has to be a global effort. And the United States must assume a leadership role, both politically and financially.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So something a little bit more like 2008-2009 in response to the global financial crisis, where the G20 was created. There was a lot of US leadership in cooperation with others. At that point the UK-US relationship was pretty crucial, but so were many others. Is that a parallel one can point to, but do it around public health rather than global finance? Although this could also be a global financial crisis.

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Yeah I was going to say, Fred, I think that we’re also going to have lingering financial ramifications from the pandemic. We’re obviously seeing very slow economic activity, some of the worst in the last fifty years in parts of Europe. And we know what the impact has been here in the United States. And we don’t have good data from the rest of the world, but obviously it’s had a global impact.

So yes, I think that there very well could be a role for the G20, working in conjunction with the UN, with the WHO, with Gavi, with others that are major players in the public-health arena, to try to learn from the mistakes that were made. Yes, I think it’s fair to say China was not as forthcoming as it needed to be, as transparent and open in the beginning. We also had an unfortunate lack of preparation or even understanding in several countries, including our own. The guidebook, the blueprint for dealing with global pandemics that the Obama administration had left for the Trump administration was disregarded.

So let us hope that individual nations will learn lessons. But let us also hope that collectively we can put together a more robust and quick international response, and get every nation to buy into it, so that you don’t have the role of any nation in the midst of a potential pandemic be to, you know, shut down and exclude investigation from international experts. We need to be more open and transparent because I fear, Fred, that, you know, this is not the last of the viruses that the world will face. In fact, I think that there’s a lot of very thoughtful analysis pointing toward this being perhaps the beginning of a continuing public-health threat that we should be better prepared for internationally. And we need to do that as quickly as possible.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Thank you, Secretary Clinton. China’s come up several times in this conversation. It seems to be the kind of peer competitor of the sort that we’ve never experienced before across so many realms—whether it’s technology, or economy, or military, et cetera, et cetera. The Trump administration has been quite outspoken, has made this a huge priority, particularly in the last weeks. They point to the past, saying that the US has ignored China for too long, and now we need to stand up. For the next president of the United States, it seems like we have an attitude, but we don’t have the strategy. What could that strategy contain?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Yeah. Well I think that, you know, we’ve gone through a number of phases with China, ever since, you know, the Nixon opening to China. And for a number of decades, it was certainly in America’s interest and the world’s interest, I would argue, to support China’s economic rise, to work to include China in the international order, in all kinds of institutional ways. But I think any relationship has to be constantly reevaluated. And as we’ve seen with Xi Jinping, a lot of the aggressive nature of China’s ambitions now are very clear militarily, and strategically, economically, internationally.

And so you require a clear and consistent approach to China, which we have not seen under the Trump administration. There have been a series of economic actions taken, not particularly effective from what I have seen, and a lot of name-calling. But in the meantime, China has extended its road-and-belt program and increased its influence, not only across Asia but into Africa, into the South Pacific, even into Europe, and certainly Latin America. China is not only building infrastructure nationally, but through a competitive infrastructure bank that it has set up.

So you see with China, they’re playing the long game. And as I say, you can’t blame a country for acting in its own self-interest. We can question ourselves for not being more effective in how we deal with China’s new, more aggressive, ambitious approach. So I think it’s important to stress that the United States is an Asian power, a Pacific power. I had those conversations even when I was secretary of state with my Chinese counterparts—that we will and intend to protect the South China Sea from colonization by Chinese military interests, that we stand with our friend and allies in Asia, East Asia, South Asia, in their efforts to protect their territorial integrity, that we should get back into the business of competing for hearts, minds, and infrastructure in different parts of the world because it does make a difference.

We did a tremendous job under President George W. Bush in fighting the AIDS epidemic in Africa, and spent many billions of dollars saving lives and providing treatment while China was building soccer stadiums and parliament buildings. But we were competing, and we had a really strong case to make that we were standing up for, you know, the human rights and the health care and the freedom of people in Africa. And basically, with Trump as president we are absent. We are absent symbolically and we are absent substantively.

So I think there’s a lot we can do to rebuild our presence. We also should not shy away from continuing to speak out about human rights in China—about the Uighurs, about the crackdown in Hong Kong. I think there’s a real audience within China and around the world for the United States regaining its voice when it comes to human rights. So there’s a real opportunity here, Fred, that I think that a Biden-Harris administration would quickly seize to try to get our relationship with China back on a steadier, more predictable course, and reassert America’s standing and leadership in Asia and beyond.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Secretary Clinton, where does Europe stand in this? Let me take you back to 2013. The Atlantic Council gave you its highest honor, the Distinguished Leadership Award. You were introduced by the Republican Henry Kissinger, just to underscore our bipartisan/nonpartisan credentials, and you spoke about the centrality of the Atlantic relationship in energy, in trade, and regarding Russia. But now China is front and center. You said America’s future is bound up in the future of Europe. Does that remain the case now, or are we just being nostalgic looking back at the transatlantic relationship? Or what role do you think it has in this very uncertain future we’re going in?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: No, I don’t think it’s nostalgia at all. I think it’s realpolitik, to use a term associated with Kissinger. (Laughs.)

I think one of the great advantages the United States historically has had, which unfortunately we have squandered in the last three and a half years, is our network of alliances. And there is none that has been more consequential and long-lasting than the Atlantic alliance.

And I believe strongly that democracy is under attack around the world. Governance has not lived up to what people living in democracies have every right to expect. We have a lot of work to do within the Atlantic alliance to rebuild the democratic pillars of our nations and our interrelationships. I still believe there is an incredibly important role for NATO. The aggressiveness of Russia, as we’ve seen it in Georgia, Ukraine, the kind of activity we’re seeing currently in [Belarus], and the kind of threats that Russia has posed to democracies from, you know, the Baltics to the Balkans, there is a great deal of work to do between Europe, the United States, and Canada in once again strengthening our democratic alliance and taking a hard look at where we have fallen short. Trying to support—as, you know, the EU has tried to do—the democratization within countries, which as we’ve seen in Hungary and Turkey and elsewhere, even, you know, NATO members, has been a bit disappointing to say the least.

So, yes, the transatlantic alliance should remain at the core of American foreign-policy vision and objectives. And I would hope that one of the first things internationally that a new administration does is to reaffirm the centrality of that Atlantic alliance.

FREDERICK KEMPE: We’re getting a number of questions in from Twitter. Many of them circle around the whole issue of civil society, your “It Takes a Village,” and particularly with Black Lives Matter. A question I would ask is the connection between that domestic health and international policy. Dean Acheson, one of our Atlantic Council founders, one of your predecessors as secretary of state, actually, wrote a letter into the amicus brief for Brown versus Board of Education in the early 1950s and he said that racial discrimination, “jeopardizes the effective maintenance of our moral leadership” among “the free and democratic nations of the world.” How do you view what’s happening right now in the country and civil society? And how does that interact with our international route?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well, I think that this is a moment of great moral reckoning over structural racism in our country. And I’m hopeful that real change will occur. The young people leading the Black Lives Matter movement, other young people who are engaged in peaceful protests, are certainly crying out for changes in many institutions and attitudes toward race and ethnicity and religion and gender in America. And it is a very serious internal threat to our way of life and to our unity. But as Dean Acheson said all those years ago, it also impacts America’s image and leadership abroad.

You know, during the 2016 campaign, Fred, one of the Russian tactics that we learned about afterward was to sow racial discord, to create phony events, to have a heavy online presence that really stoked racial animosity and fear. The Russians have been at that a very long time, as a recent excellent book by David Shimer called “Rigged” lays out. The Russians, under the Soviet Union and now the Russian Federation under Putin, have always tried to highlight racial strife and inequities in the United States as a way of undermining our aspirations for democracy, our values about moving toward a more perfect union. They’ve taken any opportunity they could to try to paint a much darker picture of the United States.

So I think both—and first probably most importantly—we’ve got to do better internally ourselves. There have been some important legislative changes in some states and cities, and there’s a good piece of legislation called the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act that actually passed on a bipartisan basis in the House of Representatives to try to deal first and foremost with injustice in policing and in the law-enforcement community and in the criminal-justice institutions, but we’ve got to go further than that. We have to be honest about the biases that often influence how we treat each other, view each other, whether or not we’re willing to make room in more ways in society for more people to have a real shot at their own opportunity and better future for themselves.

And so I hope that this moment is not lost. I hope that the kind of campaign Trump is now running, which is a very divisive one, is repudiated in our election, and that we can try to, you know, heal the country by actually taking specific steps to remedy the lingering and deeply and profoundly sad injustices that we still live with.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So not to let the moment get lost, heal the country for sure, but at the same time understand that there are foreign actors who will try to exploit our divisions. And so I think that’s a really good way to look at it.

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Right.

FREDERICK KEMPE: Another question that’s been coming in is about—questions coming in about the Middle East. Also in the news, the UAE and Israel are normalizing relations. Israel has agreed not to annex the West Bank in return for that. That would look like a victory for the Trump administration and perhaps for the Middle East. You’ve dealt a lot with the Middle East in your lifetime. How do you view this apparent breakthrough? And in general, what role would the Middle East play in another presidency? Is it more withdrawal from the region because it’s just not as important to us as it once was, or is it some other approach?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well, with the Middle East I think we should be grateful to see any progress, no matter when or how it proceeds. And this potential breakthrough is promising. We have to see that it actually takes place, and that Israel backs off of its intention to annex the West Bank. And I hope that the normalization of relations with an Arab Gulf power like the UAE will bring some stability to the situation in the Middle East. There are still so many problems that I do not see how the United States can walk away. We’ve got not only the continuing challenges of Israel’s and the Palestinian, you know, dilemma of trying to figure out how best to live together with a secure Israel, with an autonomous Palestinian entity, a state. We’ve got the tragic situation in Gaza, which has, you know, great implications for continuing conflict.

We have the collapse of Lebanon. The tragedy of the explosion in Beirut is just beyond words. What happened there and the loss of not only, oh, so much housing and business, half of the health-care facilities, the hospitals, were wiped out. The port was, you know, destroyed. You know, I feel such a sense of despair for the people of Lebanon who have been so poorly governed over the last years, and have been, you know, a pawn of Syria and its allies, and the Saudis and [their] allies. And I hope that the world, as President Macron called out, will assist Lebanon. But Lebanon has to be governed better. And, you know, the sectarian governance that put, you know, interests of groups far, far ahead of the whole has had disastrous consequences.

Look, we still have challenges in Egypt, and Libya, in Iraq, Syria obviously. And we have a changing situation in Iran. When we were talking about China earlier, one of the more interesting and potentially challenging developments is that Iran and China are entering into a military and economic agreement. And I put that directly at the door of the Trump administration—that pulled the United States out of the Iran agreement that I began the negotiations for as secretary of state, and my successor John Kerry was able to bring to a very important conclusion, to put a lid on the Iranian nuclear-weapons program.

And so by pulling out—you know, if there were problems, and of course any agreement has, the Trump administration could have sought to negotiate changes that they wished for. But instead, they pulled out, giving a green light to Iran to pursue its nuclear-weapons agenda. China is now cooperating with Iran. China was one of the countries I had to persuade to vote for international sanctions at the UN Security Council, to set the table for the negotiations. And of course, we know that if Iran pursues nuclear weapons, the Gulf states will likewise. And I cannot imagine a more dangerous situation than a nuclear-arms race in the Persian Gulf.

So there is an enormous amount at stake in the Middle East. And no responsible administration could ever walk away from that.

FREDERICK KEMPE: I’m so glad you drilled down a little deeper on Iran. And I think a lot of our viewers and Americans haven’t paid as much attention to the Chinese-Iranian recent agreement, which really does seem to be a change, does seem to be different. Do you go right back to JCPOA if you’re a newly elected President Biden? How do you manage that? Is there a lot of low-hanging fruit you can just pick up? Or has the world moved on where you need a totally different strategy? And maybe first on Iran.

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well, you know, that’s a question to be answered, Fred, because I think it would be in the United States’ interest to rejoin the Iran agreement, just as it would be to rejoin the climate agreement. We are now the only nation not in the Paris climate accord. But with respect to Iran, I think it’s important for the United States to try to not only rejoin the agreement, but to try to put that lid back on the Iranian nuclear-weapons program, and keep it firmly on, while trying to continue preventing a nuclear-arms race with the Saudis, or the Emiratis, or the Egyptians, or whoever else thinks that if Iran has a nuclear-weapon program they should have one too. And I think the best way to do that is to rejoin the agreement.

Now, at this point I don’t know whether Iran would be receptive to that. I think they may have moved on. And remember, there was always a conflict between the political and clerical leadership in Iran, and obviously the military leadership, as to whether or not to, you know, put that lid on the nuclear-weapons program under the agreement. So again, I don’t think we would know unless we resumed intensive diplomacy. But I don’t think it’s in Iran’s interests to have continuing sanctions against it. Even with, you know, Chinese support it’s not economically enough if the rest of the world, you know, does renew pressure on Iran.

So it would have to be explored. There—I can only tell you, it was very important to try to get the world behind sanctions, because remember in the George W. Bush administration for eight years—and I was there as a senator—we voted to sanction Iran on every way we could. But that was just the United States alone. And when President Obama went into office, when I became secretary of state, we saw it as essential to try to bring the world together. Not just unilateral sanctions by the United States, but the entire world. And it was difficult, because, you know, a lot of countries had very big energy deals with Iran. But we did it. We got everybody on the same page. We got the UN Security Council.

So this is doable, even though, yes, time has moved on and different relationships have developed. But you can’t tell how far you can go unless you take that first step. And I would certainly urge a new administration to tackle that as among its many important challenges right off the bat.

FREDERICK KEMPE: So, Secretary Clinton, last question, and I’ll double-barrel this one, which is the way of cheating the last question. (Laughter.) And this is such a rich conversation. You know from our previous conversations that I love the question: What keeps you up at night? You’ve outlined a world that looks pretty volatile, looks pretty dangerous. Want to get a feeling in general, in your lifetime, is this a uniquely fraught, dangerous moment? And if so, what concerns you the most? But the double barrel, in all the things we’re looking at—Iran, China, you know, North Korea, Venezuela—what worries you the most? And I think the double barrel to this is, you cared so much about soft power in your life. You were the secretary of state. What’s the status of our soft power in the world, and what role does it play in this dangerous landscape?

HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON: Well, you’re right, that is a double-barreled question. You know, I worry a lot about the spread of nuclear weapons, other dangerous weapons like, you know, biological or chemical weapons, of course. But I remain singularly focused on the spread of nuclear weapons. I would like to see a renewal of negotiation with Russia. The New START treaty that, you know, my dear friend and a great patron of the Atlantic Council, Ellen Tauscher, negotiated while she was at the State Department, is set to expire. I would like to see it renewed.

I would like to see there be ongoing dialogue with the Russians over their nuclear-weapons program, which appears to have moved into tactical nukes, and other kinds of experimental weaponry. I would like to see enormous pressure put on China to join arms-control discussions. I think that the Obama administration, in our first term we tried to set a plate for nuclear strategic summitry. We had several meetings, bringing together the countries with known nuclear weapons programs and those that had an interest in trying to control the spread of nuclear weapons.

I think that has to be renewed and deepened, because, you know, I fear not only the rogue nation like North Korea, but the accident, the takeover of a nuclear program in a country by extremists of whatever stripe they might be, or criminal elements who are in the marketplace on a regular basis trying to buy or sell nuclear material that could at least go into a dirty bomb. So that would be my number-one concern, you know, with biological and chemical weaponry also needing to be paid attention to.

I think we also have to, as I said earlier, strengthen our international public-health response to potential pandemics. We’ve got to take seriously the security implications of climate change. That was something I started focusing on when I served on the Armed Services Committee in the Senate. We’re going to see mass migrations. We’re going to see increasing conflict over water and land because of climate change. We’re ill prepared for that. The temperature in Baghdad has broken all records. I just can’t really underscore strongly enough how climate change is a security challenge that has to be addressed.

So those are the areas that I would pay immediate attention to. And as to soft power, Fred, you know, I think we have squandered our soft power. I don’t think that the United States has the influence that we should have in global debates or in how we’re viewed, particularly by young people around the world. I think we have to rebuild our soft power. I like the phrase “smart power” because I think it combines the elements of the hard power that is necessary in defense with the soft power that is often viewed as part of development and diplomacy.

But we’ve got to smarten up our global presence and once again try to influence people and events through the power of our example, and—as opposed to the example of our power. That is an old cliché, but it’s really an important one to keep in mind. You know, we have to set the standard for a rules-based global order, and it is very much in America’s interest but also in the world’s that we assume that leadership position again.

FREDERICK KEMPE: What a terrific close to this opening event of Elections 2020: America’s Role in the World—that we have to be the power of our example rather than the example of our power and set the example for the rules-based order that, after all, we, with our allies and friends, created in the first place. So, Secretary Clinton, thank you so much for this enormously rich conversation.

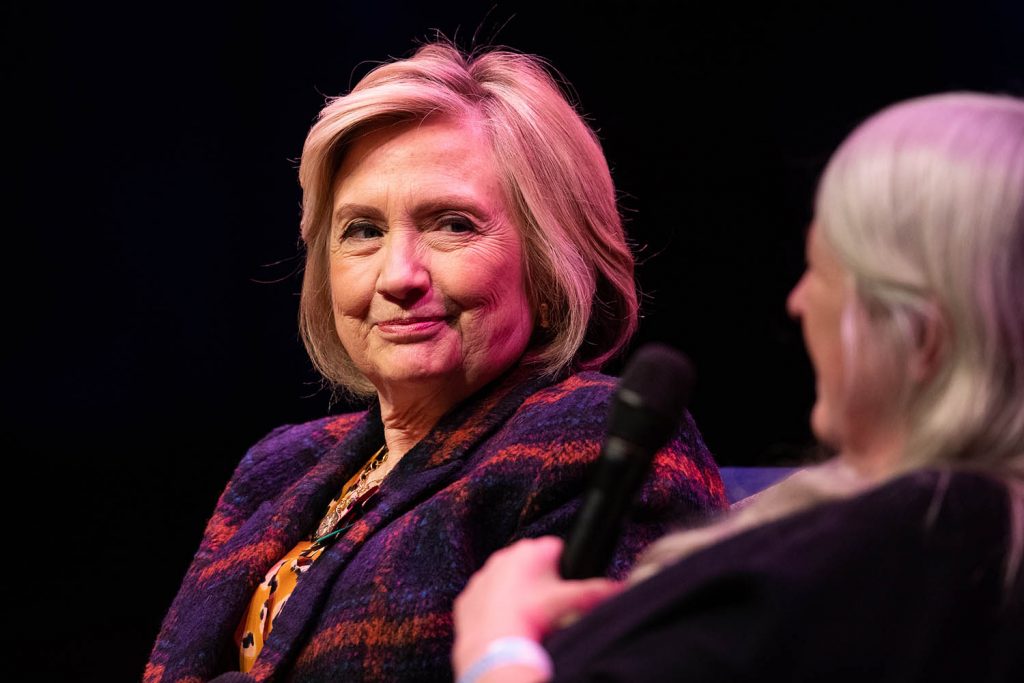

Image: Hillary Clinton (left) talking to Mary Beard at the Southbank Centre in London at the launch of Gutsy Women: Favourite Stories of Courage and Resilience a book by Chelsea Clinton and Hillary Clinton about women who have inspired them. PA Photo. Picture date: Sunday November 10, 2019. Photo credit: Aaron Chown/PA Wire via Reuters