On February 9, 2020—only days before Valentine’s Day—twenty-five-year-old Ingrid Escamilla was murdered by her partner in Mexico. Photos of her body were splattered on newspapers across the country. Days later, seven-year-old Fatima Aldriguett Antón was tortured and killed, further sparking outrage. Thousands of protestors took to the streets in response to these killings—outside Mexico’s presidential palace, protestors called for concrete government action against the country’s femicide epidemic. They spoke out by throwing red paint onto the building and spray-painting the names of femicide victims on its walls.

Sadly, Ingrid and Fatima’s deaths are just a symptom of an all-too-common occurrence—every day in Mexico, ten women are killed on the basis of gender. Fewer than five percent of those murders are ever solved and the justice system rarely presses charges.

Calls for action are growing louder; the protests are calling attention to the Mexican government’s failure to release any plan to prevent femicides, as well as to the media’s coverage of the issue, which they say gives too much space to the abuser’s testimony and not enough respect to the victim’s life and body.

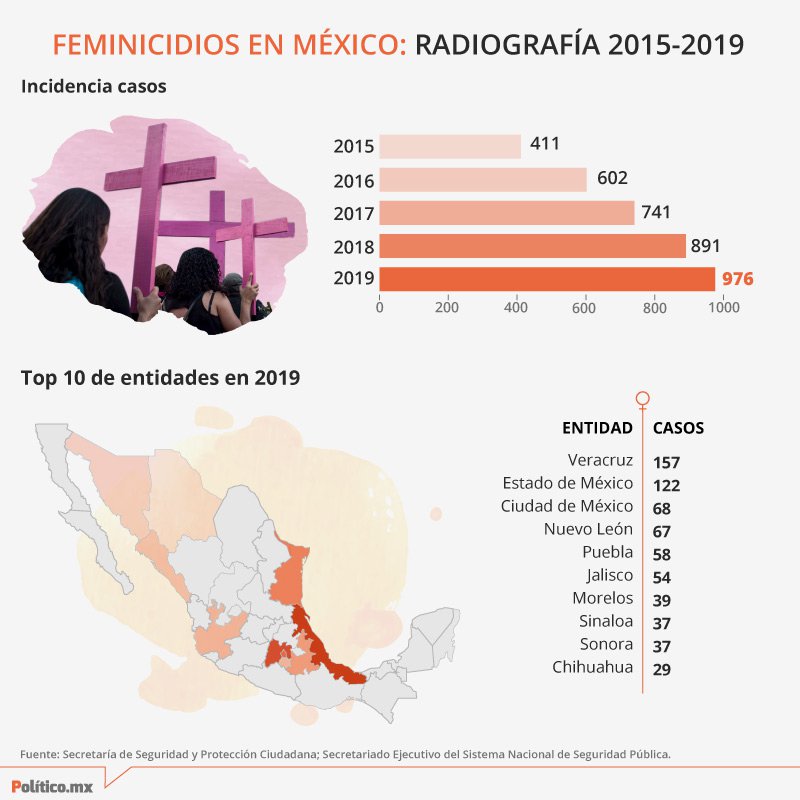

Mexico has legally distinguished femicide from homicide since 2012, applying a gender-based lens when looking at homicides of women. Seventeen other countries in Latin America have made similar distinctions for femicides, charges that often carry harsher punishments. However, this February, the Mexican government debated eliminating that distinction from their penal code, despite the attorney general reporting a 137 percent increase in femicides in the country over the last five years—four times more than other homicides. Facing backlash for comments blaming femicide on corruption and past economic policies, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador eventually conceded that he did not agree with the proposed changes to the penal code concerning femicide, and those changes have not been implemented.

But, femicides are not just common in Mexico—they are prevalent throughout the region. Global data is difficult to gather due to differences in reporting standards and data segregation practices, and published findings vary. However, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) aggregated data from 2018 of women killed by a partner or family member and found that African women are murdered at a rate of 3.1 per 100,000, with the Americas in second place at a rate of 1.6 per 100,000 women. The 2016 publication “A Gendered Analysis of Violent Deaths” reported that fourteen of the twenty-five countries with the highest femicide rates are Latin American. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL) announced in November 2019 that they are working on a registration system for femicides that will account for all of Latin America and the Caribbean, so future data can be standardized.

Although specific rates vary widely, El Salvador (between 6.1 to 13.9 femicides per 100,000 women) and Honduras (between 5.1 and 32.7 femicides per 100,000 women) are consistently within the top five countries worldwide in terms of femicide rates. In areas of war or other conflicts, like in the Northern Triangle countries, it is more difficult to determine how many murders of women are gender-based, thus femicides, or casualties of conflict and thus homicides. Brazil sees the most femicides annually (over 1,200 in 2018, making its rate 1.1 per 100,000 women), but is sometimes excluded from data analyses because their system of registration and data storage for femicides is among the worst in the world. Colombia has seen an increase over the past two years in femicides, now experiencing an average of one femicide every two days. Argentina had the third-highest number of femicides in 2018 (255), a rate of 1.1 per 100,000 women.

Chile experiences lower rates of femicide than other countries—forty-five femicides in 2019 and another 107 reported attempts—but their protests against gender-based violence in last year made headlines for the chant “rapist in your path” (violador en tu camino). The song pinpoints the government—specifically the justice system—as complicit in the ongoing violence because of their lack of action against perpetrators and against the epidemic as a whole. This is a common sentiment, as demonstrated by the widespread use of the chant in Latin America and even Europe.

In Peruvian media, it has become impossible to avoid the topic of femicides. Cases occur every day, averaging more than 100 per year. Reports of attempted femicides are on the rise, likely affected not only by the actual frequency of the crime, but also by the increasing willingness of women and their families to report these events. The Peruvian government is working to incentivize women to report by providing them with a government-backed system of support. The media also work to make women feel safer by reporting not only on the crime, but also on the sentences that perpetrators are given—which can be up to thirty years.

With the 2016 creation of the national plan against gender-based violence, the Peruvian government publicly acknowledged the epidemic and placed it as a government priority for years to come. Several agencies with specialized task forces now work toward femicide reduction and prosecuting the abusers, including emergency centers for women, a hotline for victims of violence against women, and the Specialized Police Squad for Prevention Against Domestic Violence.

Simultaneously, the Peruvian government is implementing long-term policies to break the cycle of violence for children who fall victim to domestic violence. Programs include a special unit that protects the rights of children orphaned by the murder of their mother, or for survivors that were disabled by the act of violence against them. The latest addition to this set of policies is a cash transfer to victims’ children, where the child’s caregiver receives 600 Peruvian Sol every two months ($177, or one-third of a monthly minimum wage). The Peruvian programs against femicide are new, so it is too early to determine their effectiveness. However, these programs appear rather comprehensive and other countries could benefit from following some of these initiatives.

To address and reduce femicides across Latin America, countries should consider the following recommendations:

Acknowledging the problem

The first step to action is official acknowledgement of the problem. Some countries have established Ministries of Women. Chile’s legislature declared December 19 as the National Day Against Femicide. The United Nations established a Spotlight Initiative in 2017 that raises awareness of violence against women and runs violence prevention programs in Latin America and Africa. Further increasing visibility of the femicide epidemic can help break down stigma against reporting acts of gender-based violence.

Establishing a clear legal framework for addressing cases of femicide

In addition to visibility, establishing a clear legal framework for reporting and prosecuting femicide is important to combatting the femicide epidemic. Legally distinguishing femicide from homicide allows for investigations to be conducted with a gender-based lens and for perpetrators of femicide to face distinct punishments. In Panama, the minimum prison sentence increases to twenty-five years for femicide, five more than for aggravated homicide. Honduras punishes femicide with thirty to forty years in prison, while aggravated homicide carries a sentence of twenty to thirty years. Mexico’s federal punishment for femicide is forty to sixty years and a fine, though their congress is voting to increase it to sixty-five—meanwhile perpetrators of aggravated homicide face thirty to sixty years, although a judge did sentence a murderer to life in prison in 2018.

Although it is increasingly common for countries around the world to distinguish gender-based violence from other crimes, few countries outside of Latin America—and none in Europe—use the word femicide in any legal capacity. In this, Latin America is leading the way, as seventeen Latin American countries currently have laws defining femicide and articulating specific sentences. Some, such as Mexico, however, require the crime to involve sexual abuse or for the perpetrator to be related to the victim in order for the crime to qualify as femicide. Only in January did Chile begin to include murders by boyfriends, in addition to husbands, in statistical reporting about femicide.

Placing restrictions on the definition also restricts the potential response. Defining femicide as the killing of a woman or girl on the basis of her gender encompasses all applicable acts of violence, while still segregating these crimes from homicides so that they may be more effectively prevented.

Establishing specialized offices or task forces for the prosecution of femicide cases

Establishing specific prosecution offices or other task forces that specialize in femicide—in the same way countries establish drug-related task forces or corruption organizations—is another important step that law enforcement can take. This will not only help with prosecution and prevention of femicide cases, but also sends a public message that the legal system takes these cases seriously. Recommending harsher sentences for perpetrators of femicide is only effective if those perpetrators can be caught and charged.

Working with media to shed light on perpetrators

Media dissemination of killers’ sentences will send the same message. Ensuring that there are resources available to women who report—and that they can access them—can also give victims the push to report abuse before it escalates to femicide.

Education as a long-term sustainable solution

For long-term reduction in femicides, education around gender-equality efforts is crucial. More education systems are beginning to include gender studies in their curricula, which educate boys and girls from a young age about the concept of equal rights. Though some of these programs face backlash, acknowledgement of gender-based violence, and education around the topic, will be an effective step toward eliminating the femicide epidemic in the region.

Isabel Kennon and Grace Valdevitt are interns at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Image: Women raise their hands as they protest against gender violence and femicide in Puebla, Mexico, February 22, 2020. REUTERS/Imelda Medina