Civil war, debt, and Ethiopia’s road to recovery

table of contents

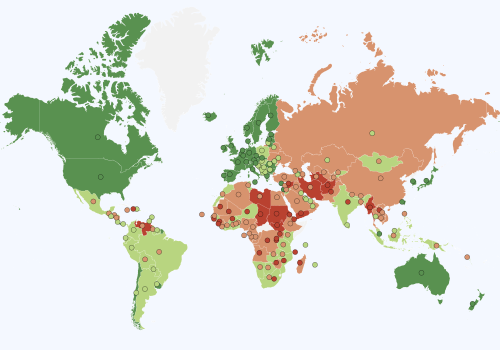

Evolution of freedom

Since 2000, Ethiopia has achieved remarkable economic growth, driven by public investment in infrastructure and industrial expansion, positioning itself as one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies. Coupled with extensive construction projects, the service and agricultural sectors also made modest contributions. However, since 2020, the country has faced significant setbacks, including internal conflicts that disrupted production and trade, alongside the global COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated supply chain disruptions and weakened demand for exports. These challenges were further compounded by rising inflation, which strained household incomes and increased the cost of living, and a severe shortage of international reserves, making it difficult to stabilize its currency. The recent decision to float the Ethiopian birr has added to the volatility, causing currency fluctuations that have increased uncertainty in trade and investment flows. These converging shocks have placed immense pressure on Ethiopia’s economic stability, underscoring the need for carefully managed reforms and international support to restore macroeconomic balance.

The Freedom Index portrays a realistic picture of the politico-economic development of Ethiopia in the past three decades. The rapid improvement on the economic subindex around the turn of the century illustrates the country’s sustained strong economic growth in that period. More recently, this subindex reflects the euphoric momentum that came with a new administration in 2018, promising additional economic liberalization in trade and investment. I think the rise observed in the property rights component starting in the early 2000s is also a product of an effort to better protect foreign investment.

Unfortunately, these improvements were not very long-lived, with scores on the investment freedom component dropping first, followed by declines in the trade and property rights components a few years later. 2020 appears to be a clear inflection point, with the expansion of internal conflicts in the country—starting with war in Tigray—that have been devastating for the economic climate. Along with the war, the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and supply chain disruption exacerbated the economic development challenges. Some of the industrial zones in areas of conflict are now difficult to access, and the lack of stability makes it harder to retain and attract foreign investors. A dramatic example of the effects of these protracted conflicts since November 2020 is the fact that Ethiopia lost its beneficiary status under the African Growth and Opportunity Act in 2022. This dented the country’s ability to propel its economic development via export growth.

The women’s economic freedom component shows an optimistic view of the situation for women in Ethiopia. In terms of legislation, especially at a federal level, it is true that the economic rights of women have come closer to that of males since 1995. Raising the legal marriage age to eighteen since 2000 has helped reduce child marriage rates, ensuring that young people have more time to complete their education and achieve better economic outcomes. The strict enforcement of the legal marriage age legislation is essential to tackle child marriage problems in some regions, such as Amhara, where the incidence of child marriage was persistently high in the past. Enforcement across all regions in the country contributes to improved health, educational attainment, labor market outcomes, and well-being for young women by allowing them to marry at a more mature age, thereby decreasing the risks and complications associated with early pregnancies. So, the improvement in the legal framework for women, particularly around economic issues, is probably what is being captured in this component, and it is also true that we now see a larger share of women in top government positions, including ministerial posts.

Nonetheless, the implementation of gender equality more generally and at all levels of society is probably a much harder task. There is still significant cultural resistance in some regions and ethnic groups; for example, some impose informal limits on the assets that women can inherit. My own research on the topic shows that the school-to-work transition remains very challenging for many women, especially when they turn eighteen and the pressure to marry is intense, particularly in rural and remote areas.

The political subindex clearly captures the excitement of the country when the current administration came to power. However, the regressive nature of the new government—responding both to internal and external factors—became immediately clear, in terms of civil liberties and political rights. In recent years, the country has been going through civil conflicts, a cost-of-living crisis, high levels of indebtedness, and tight monetary policy. These, combined with global factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine-Russia war, have been detrimental for Ethiopia and the welfare of its population. If the current trajectory continues, the near future is worrisome.

The unexpectedly high score on the election component may stem from a limited interpretation of this variable. While elections do take place, the system does not yet fully embody a completely democratic political structure with guaranteed political and civil liberties and a robust system of checks and balances on the executive. Ethiopia has no history of a meaningful political opposition. The legislative constraints on the government are very low, which explains, in part, the developments of the past thirty years.

The low level of the legal subindex components accurately shows the poor state of the rule of law in Ethiopia—a common problem in many African countries. I am somewhat surprised by the relatively good and rising performance of informality, which is probably due to the obvious difficulties in measuring the size of the informal economy and the share of the informal sector in employment. My own research, using the harmonized World Bank Enterprise Surveys, shows a persistently high level of informality in the enterprise sector. Another potential problem with this component is that informality is not a binary phenomenon, but a continuum, as firms navigate the formal and informal sectors simultaneously, making the actual share of the informal economy—and the number of individuals engaged in it—even harder to measure.

The sharp drop in security starting from 2020 is explained by the proliferation of internal conflicts and fighting between the federal government and various groups in regions such as Tigray, Amhara, and Oromia. The Pretoria Agreement of November 2022 may have slightly improved the situation by stopping the war in Tigray, but the ongoing conflicts in Amhara, Oromia, and elsewhere could jeopardize those security improvements, and the overall future stability of the country.

Evolution of prosperity

The significant rise in the Prosperity Index since 1995 is noteworthy, but it is important to consider the very low initial levels in areas like income, education, and health. While the country remains one of the least prosperous globally and has yet to reach the average level for Sub-Saharan Africa, the substantial progress, especially since 2000, is undeniable.

The rise in income starting around the turn of the century is substantial. When initial conditions are at a very low level of economic development, any form of growth and stability favors the reallocation of resources to more productive uses and rapidly shows up in gross domestic product (GDP) measures. Sectors like construction and infrastructure clearly benefit from a more stable macroeconomic framework, boosting income growth. For the first two decades of the twenty-first century, growth was propelled mainly by strong public investment. However, the most important question is whether the increase in GDP has been adequately and fairly distributed. The inequality component for Ethiopia, based on the Gini coefficient, is in line with other aggregate measures of inequality. Nonetheless, when you focus on the lower end of the income distribution, the bottom 20 percent, the situation is not so optimistic, and is probably worsening, pointing to the lack of inclusion and progressive redistribution. There are also important disparities across Ethiopia’s regions that are usually not well captured by data, as these are mainly collected in the larger cities.

The extraordinary increase in Ethiopia’s health component can be attributed to the extensive work of grassroots service providers, expanding healthcare and coverage in line with policies since 2000 (e.g., the use of health extension workers). Broadly speaking, the country focused on improving primary and preventive healthcare, which produced a sharp drop in child mortality and adult morbidity over the past three decades, though maternal mortality remains a significant problem. The small dip on this component since 2019 is not only due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which was not so severe in health terms as in Europe, but also to the deaths related to armed conflicts.

In any case, while Ethiopia has been meeting the Millennium Development Goals and is even ahead of schedule for indicators such as child mortality, there is a long way to go if the country is to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Despite progress in terms of GDP growth, Ethiopia still faces complex economic challenges including the prevalence of poverty, inequality, malnutrition, and destitution.

Regarding education, the graph clearly captures the significant improvement in schooling rates, which have increased in all levels of the educational system, for both males and females. However, quality has been an issue, and our graduates are not as well prepared as these data suggest. As an example, think of the investments carried out by the Chinese government in the last two decades. The Chinese investors came to Ethiopia because labor is relatively cheap, but they have realized that the skills and human capital of many of the workers they hired are very poor, to the extent that they have even needed to send them to Beijing to train. To make headway in education, the country needs to “invest in learning” and development of cognitive and other skills for better employability of graduates. This necessitates a paradigm shift away from the usual culture of “spending on schooling” which simply focuses on completing a given schooling cycle, with little attention paid to acquiring employable skills and other practical outcomes for learners.

The very low level of the minorities component reflects a recurrent problem of the Ethiopian institutional environment: the close alignment of political power and access to services and opportunities. That is, economic growth has failed to be inclusive of all societal groups. The current administration must reverse this tendency so that the proceeds of economic growth reach the wider population. Children, youth, women, the disabled, and the elderly should not be neglected, and the economic management should give utmost priority to have a social protection angle in the ongoing reforms and policy measures.

The path forward

The current and future challenges for Ethiopia are enormous. First and foremost, the various armed conflicts around the country are the biggest impediment to movement of labor, traded goods, and execution of productive activities. If peace and security are not restored in all regions of the country, there will be further deterioration of the socioeconomic situation nationwide. Agricultural and industrial production, and other employment-generating economic activities such as trade and investment, continue to suffer.

It will be difficult to attract domestic and foreign investors, who are critical to revive the ailing economy in a situation of insecurity and uncertainty. Economic growth will not be able to maintain the pace of the first two decades of the twenty-first century. The debt problem in the country dented the confidence of investors and the country’s credit rating and/or worthiness suffer consequently. Macroeconomic management will be a major challenge in the context of very limited international reserves, devalued currency, and high levels of debt repayments with high cost of capital. The relatively easy access Ethiopia has enjoyed to international capital markets and bilateral lending from countries like China can suddenly become a problem. China, with its aid (e.g., lending for road and other infrastructure projects), might offer benefits in the present but at a very high cost in the future. But the debt problem Ethiopia faces is not only the making of China; it has been a problem for several years and borrowing from other sources such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank contribute to current debt levels.

Another big challenge that Ethiopia faces is the alarming demographic trend. Even if there has not been a census in the country since 2007, some global estimates put the population at around 120 million and growing. This demographic situation poses a major challenge for attaining food security and creating enough jobs for the growing young and educated population. Each year, two to three million young Ethiopians enter the labor force, and it is clear that the labor market cannot absorb such a huge number of workers. Any hope of transforming the economy—or even of gaining a meaningful grip on it—is an elusive dream in a country where there are high levels of unemployment, poverty, inequality, destitution, internal conflicts, food insecurity, and an ever-growing and underskilled youth population.

Addressing the challenges facing Ethiopia requires more than just external assistance; it demands the implementation of robust public policies that focus on aiding the poor, youth, and women, all within a framework that fosters inclusive economic growth. While Ethiopia’s strategic importance to global powers, including the United States, might influence the flow of foreign aid from organizations like the International Monetary Fund, the impact of such aid (in the form of grants and/or loans) will depend heavily on the conditions attached to it and how Ethiopia uses the aid for growth enhancing, productive, and poverty-reducing activities. If strict fiscal consolidation is enforced, it could exacerbate inequality and worsen conditions for the most vulnerable populations, potentially leading to increased poverty and destitution. My concern for Ethiopia is profound, and I hope that an end to conflicts will soon allow the country to return to the better economic path it was on before 2020.

Abbi Kedir is the director of research at the African Economic Research Consortium based in Nairobi, Kenya. Kedir was an associate professor in international business at the University of Sheffield, UK, from 2016 to 2023. Kedir has authored more than fifty journal articles and is an editorial board member of the Journal of Development Studies, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, Economies, and Frontiers in Environmental Science.

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the data

About the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: Ethiopian girls carry their national flags during a rally by the ruling party in the Oromia region, May 16, 2010. TREUTERS/Barry Malone

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media