Call it lunar politics.

This week Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, signed an agreement with the Chinese National Space Administration to create an International Scientific Lunar Station “with open access to all interested nations and international partners.” It was the most dramatic sign yet that Moscow sees its space future with China and not the United States, further underscoring its growing strategic alignment with Beijing.

That follows a quarter-century of US-Russian space cooperation, launched by those who dreamed of a post-Cold War reconciliation between Moscow and Washington. The high point was the building and operating of the International Space Station.

This week’s agreement also marked an apparent rebuke of NASA’s invitation for Russia to join the Artemis project, named for Apollo’s twin sister, which aims to put the first woman and next man on the moon by 2024. With international partners, Artemis would also explore the lunar surface more thoroughly than ever before, employing advanced technologies.

“They see their program not as international, but similar to NATO,” sneered Dmitry Rogozin, the director general of Roscosmos, last year. Rogozin did a lot of sneering previously in Brussels as the former Russian ambassador to NATO. “We are not interested in participating in such a project.”

Get the Inflection Points newsletter

Subscribe to Frederick Kempe’s weekly Inflection Points column, which focuses on the global challenges facing the United States and how to best address them.

Assessing Putin’s capabilities and vulnerabilities

Rather than dwell on what all this means for the future of space, it is perhaps more important for the Biden administration to reflect on how this latest news should be factored into its emerging approach to Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

US President Joe Biden has no illusions about Putin, showing that he will engage when he concludes it is in the United States’ interest and he will sanction when necessary. His first foreign-policy win was a deal with Putin to extend the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which marked a departure from former President Donald Trump’s approach to arms control.

That said, Biden also imposed new sanctions on Russia, in concert with the European Union, after the poisoning and imprisoning of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. It remains to be seen how the Biden administration will act on existing or implement new US sanctions against the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, the most active issue currently dividing the EU and even German politics.

Whatever course Biden chooses, he would be wise not to compound the mistakes of previous administrations due to misperceptions about Russia’s decline or too singular a focus on Beijing.

“Putin does not wield the same power that his Soviet predecessors did in the 1970s or that Chinese President Xi Jinping does today,” writes Michael McFaul, US ambassador to Russia under former President Barack Obama, in Foreign Affairs. “But neither is Russia the weak and dilapidated state that it was in the 1990s. It has reemerged, despite negative demographic trends and the rollback of market reforms, as one of the world’s most powerful countries—with significantly more military, cyber, economic, and ideological might than most Americans appreciate.”

McFaul notes that Russia has modernized its nuclear weapons, while the United States has not, and it has significantly upgraded its conventional military. Russia has the eleventh-largest economy in the world, with a per-capita gross domestic product larger than that of China.

“Putin has also made major investments in space weapons, intelligence, and cyber-capabilities, about which the United States learned the hard way,” writes McFaul, referring to the major cyberattack that was revealed earlier this year after Russia penetrated multiple parts of the US government and thousands of other organizations.

At the same time, Putin is showing less restraint in how aggressively he counters domestic opponents, defies Western powers, and appears willing to take risks to achieve a dual motive: restoring Russia’s standing and influence and reducing that of the United States.

Henry Foy, the Financial Times’ Moscow bureau chief, this weekend lays out a compelling narrative on today’s Russia under the headline, “Vladimir Putin’s brutal third act.”

Writes Foy: “After 20 years in which Putin’s rule was propped up first by economic prosperity and then by pugnacious patriotism his government has now pivoted to repression as the central tool of retaining power.”

The world has seen that graphically in the poisoning of Navalny, and then in his arrest when he returned to Russia after recovering in a German hospital. Foy also reports on a “blizzard of laws” passed late last year that crack down on existing and would-be opponents. The latest move came Saturday as Russian authorities detained 200 local politicians, including some of the highest-profile opposition figures, at a Moscow protest.

Some see Putin’s increasingly ruthless dousing of dissent and widespread arrests, amid the size and breadth of protests in support of Navalny, as a sign of Putin’s growing vulnerability.

Yet others see his actions since the seizure of Crimea in 2014, right up until the apparent latest cyberattacks, as evidence of his increased capabilities. They warn of more brazen actions ahead.

Both views are right—Putin is more vulnerable and capable simultaneously. His oppression at home and assertiveness abroad are two sides of the same man.

US misperceptions about Russia’s decline hold strategy back

So, what to do about it?

The Atlantic Council, the organization where I serve as president and CEO, had an unusual public dust-up of feuding staff voices this week over what is the right course for dealing with Putin’s Russia.

The arguments focused on how prominent a role human-rights concerns should play in framing US policy toward Moscow.

Wherever one comes down on that issue, what is hard to dispute is that Russia’s growing strategic bond with China, underscored by this week’s moonshot agreement, is just one piece among a growing mountain of evidence that the Western approach to Moscow over the past twenty years has failed to produce the desired results.

What is urgently needed is a Biden administration review of Russia strategy that starts by recognizing that misperceptions about Russia’s decline have clouded the need for a more strategic approach.

It should be one that combines more attractive elements of engagement with more sophisticated forms of containment alongside partners. It will require patience and partners.

What is required is strategic context for the patchwork of actions and policies regarding Russia: new or existing economic sanctions regimes against Russia, a potential response to the latest cyberattacks, more effective ways of countering disinformation, and a more creative response to growing Chinese-Russian strategic cooperation.

Overreaction is never good policy but underestimation of Russia is, for the moment, the far greater danger.

The long-term goal should be what those at NASA hoped for twenty-five years ago—US-Russian reconciliation and cooperation. Then put that in the context of a Europe whole and free and at peace where Russia finds its rightful place, the dream articulated by former US President George H.W. Bush just months before the Berlin Wall fell.

Whatever Putin may want, it’s hard to believe that Russians wouldn’t prefer this outcome even to a Sino-Russian moon landing.

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

THE WEEK’S TOP READS

#1 The brutal third act of Vladimir Putin

Henry Foy / FINANCIAL TIMES

This week’s must-read comes from the FT’s Henry Foy on “Vladimir Putin’s brutal third act”—the cover story from the publication’s weekend Life & Arts section.

He tracks how Russia’s leader first cast himself as the bringer of prosperity, then as the anti-West patriot. But as protests grow, he is morphing into the role of brutal strongman.

“After 20 years in which Putin’s rule was propped up first by economic prosperity and then by pugnacious patriotism, his government has now pivoted to repression as the central tool of retaining power,” he writes.

We are left hoping this is the final act. Read More →

#2 Back to Basics on Russia Policy

Eugene Rumer and Andrew S. Weiss / CARNEGIE ENDOWMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE

Eugene Rumer and Andrew Weiss deliver a comprehensive transatlantic approach for Russia via the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. This one should be the basis for common cause as of great historic consequence as the aim of “Europe Whole and Free” during the Cold War.

The authors, acknowledging that the West’s policy towards Russia has for years missed the mark, argue that the United States and Europe need to go “back to basics” by reconciling their different visions for Russia and finding compromise on a coordinated strategy in areas such as sanctions, bolstering deterrence, and Ukraine. Read More →

#3 How Biden’s Experience Could Make or Break His Middle East Policy

Ahmed Charai / NATIONAL INTEREST

Writing in the National Interest, Atlantic Council Board Director Ahmed Charai discusses the major flashpoints Biden and his cadre of experienced foreign-policy experts will have to face over the next four years in the Middle East: how to rein in Iran and its proxies, how to end the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, and how best to manage complex relations with Saudi Arabia.

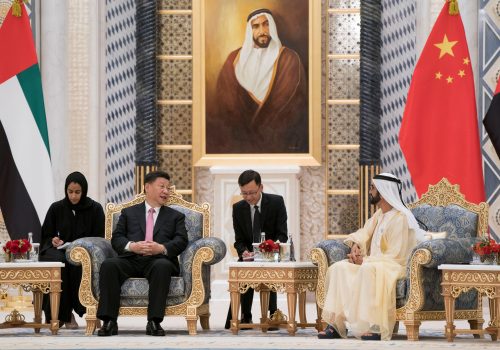

A good place to start would be for the Biden administration to build on the promise of the Abraham Accords, normalization agreements with Israel that now include the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan.

“The world has changed dramatically in the past four years, perhaps more so than in the past thirty,” he writes. “The biggest challenge of Biden’s foreign policy team: Can they adapt solutions from their prior experience without being trapped by it?” Read More →

#4 A viral tsunami: How the underestimated coronavirus took over the world

Joel Achenbach, Ariana Eunjung Cha, and Frances Stead Sellers / THE WASHINGTON POST

It has now been a very long year since the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a global pandemic.

To explain how coronavirus took over the world, Joel Achenbach, Ariana Eunjung Cha, and Frances Stead Sellers in The Washington Post call on health experts from around the globe to recount stories of government failure, complacency, and the unpredictability of COVID-19.

They write that “postmortems, when they are written, will note that experts had been warning of a viral pandemic for many years. This was not a ‘black swan’ event, not a ‘perfect storm.’ A viral pandemic is an obvious vulnerability in this age of economic globalization, when nearly 8 billion people and their parasitic viruses are highly networked and mobile.” Read More →

#5 Why We Care About the Royal Family Feud

Peggy Noonan / THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

I did not think I could stand to read another word about Oprah Winfrey’s conversation with Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. Then Peggy Noonan weighed in, and who could resist?

She doesn’t hold punches as she speaks to the “performative” side of Markle, a professional actress who, as Markle herself explained, like “the Little Mermaid,” lost and then regained her voice. Writes Noonan, “Both Meghan and Harry speak a kind of woke-corporate communications language that is smooth and calming but also slippery and opaque. You can never quite get your hands around the thought as you grab for meaning.”

But here is the deeper significance Noonan found in the interview: “It was history, a full-bore assault on an institution, the British monarchy, that has endured more than 1,000 years.”

Read this one—unless you can resist it! Read More →

Atlantic Council top reads

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a meeting with government members via a video link in Moscow, Russia March 10, 2021. Sputnik/Alexei Druzhinin/Kremlin via REUTERS