On May 13, 2020, the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security hosted a strategy consortium with a small group of experts and officials to discuss the evolution of the Russia-China relationship and how the United States and its allies should navigate it. This paper summarizes many of the points made during this meeting.

Background: The Nature and Trajectory of the Russia-China Relationship

In recent years, Russia and China have become increasingly aligned strategically, even though they have not formed a formal alliance. Russian and Chinese leaders share an authoritarian ideological orientation and perceive American power and democratic values as a threat. They are working together more closely to disrupt the US-led, rules-based global system, undermine American influence, and discredit the American political, economic, and social system. Their cooperation is especially strong in the military, cyber, diplomatic, and economic domains:

- Military: Since 2016, Russia and China have conducted joint military exercises in Asia and Europe. They are also cooperating on arms production and satellite systems.

- Cyber and Technology: The Chinese company Huawei is currently developing Russia’s 5G data system. More broadly, China and Russia are coordinating on improving cyber capabilities.

- Diplomacy: Russia and China consistently align with one another in international fora (voting together at the United Nations, China refusing as a UN Security Council member to condemn Russia’s bombing campaign in Syria, etc.).

- Economy: Russia and China are cooperating on energy deals, including a $55 billion gas pipeline from Siberia to China. In 2019, their bilateral trade exceeded $100 billion. Today, China is Russia’s largest trading partner and Russia is China’s largest oil supplier.

Although Russia and China are increasingly strategically aligned, it is unlikely that they will form a deep and trusting security alliance. There are real, enduring sources of friction in the relationship. The Russians claim, for example, that their new, nuclear-capable intermediate-range missiles are intended in part to deter China. Economic cooperation between Russia and China in the Arctic has grown, but the issue of Arctic governance remains an area of significant tension given Moscow’s Arctic security interests. In February 2015, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu expressed agitation over how non-Arctic states (China) “obstinately strive for the Arctic.” China is not likely to accept the idea of playing a tangential role in Arctic decision-making.

Moreover, while Russia and China are bound by authoritarian ideology and negative views of the United States and of Western values, they lack deeply rooted cultural or other ties. The relationship is currently top-down, heavily driven by the countries’ respective leaders. A change of leadership in either country could alter the direction and/or intensity of the partnership.

Finally, autocracies have historically tended to be unreliable partners. Russia’s history over the past century, for example, shows that it often engaged in military conflict with formal “allies.” It fought Nazi Germany during World War II, invaded Warsaw Pact members Hungary and Czechoslovakia, engaged in the Sino-Soviet border conflict of 1969, and invaded then-Commonwealth of Independent States members Georgia and Ukraine.

Implications for US National Security

The United States and its allies should be wary of a hostile strategic alignment of autocratic great-power rivals. The United States and its allies should take the following steps:

Recommendations:

- Do not assume that Russia can be turned against China. Some argue that the United States should seek to turn Russia against China, but this will be difficult if not impossible to execute in practice. There are shared interests pushing these regimes together, and neither wants hostile relations with the other. The concessions required to get Russian President Vladimir Putin to consider switching sides would be too great, and we could not trust Putin’s word even if he gave it to us.

- Manage Russia, prioritize China. Unfortunately, this means that the United States and its allies will need to contend with Russia and China at the same time. Since China is the greater long-term challenge, the United States should seek to manage Russia as part of a broader strategy that prioritizes China. The United States should also be prepared to talk to Russia about the challenges presented by China to both countries.

- Leverage alliances. The United States should strengthen its relationships with allies and partners to deal with the challenge from China and Russia. Working with allies is critical because the United States and its formal treaty allies still retain a preponderance of power (59 percent of global gross domestic product or GDP) over a combined Chinese and Russian threat (19 percent of global GDP).

- Recognize that Russia and China have differences. While turning Russia against China may not be feasible, the United States and its allies should spotlight issues where Moscow and Beijing have differences. China, for example, has not formally endorsed Russia’s annexation of territory in Georgia, and Russia has not given its full backing to China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. Central Asia is a potential area of tension as both countries are trying to reestablish their influence there. Russia is concerned about China’s growing nuclear arsenal and intermediate-range missiles. The United States and its allies could try to bring these issues to the fore and force Russia and China to confront areas of disagreement.

- Don’t assume that Russia is wholly comfortable with China. The United States may be able to play to Russia’s national pride and anxieties about its geography to drive a wedge between Moscow and Beijing. Russia prides itself on being a great power, and it may be reluctant to play the junior partner to its rising neighbor. These fears could be exacerbated if China continues to overplay its hand in international affairs. In addition, Russia worries about geographic vulnerabilities and has fought a border conflict with China in the past. Although Russia currently perceives the United States as a greater threat than China, China remains the closer power geographically. Highlighting Russia’s junior-partner status and its geographic vulnerabilities may contribute to Russian fears of, and resentment toward, China.

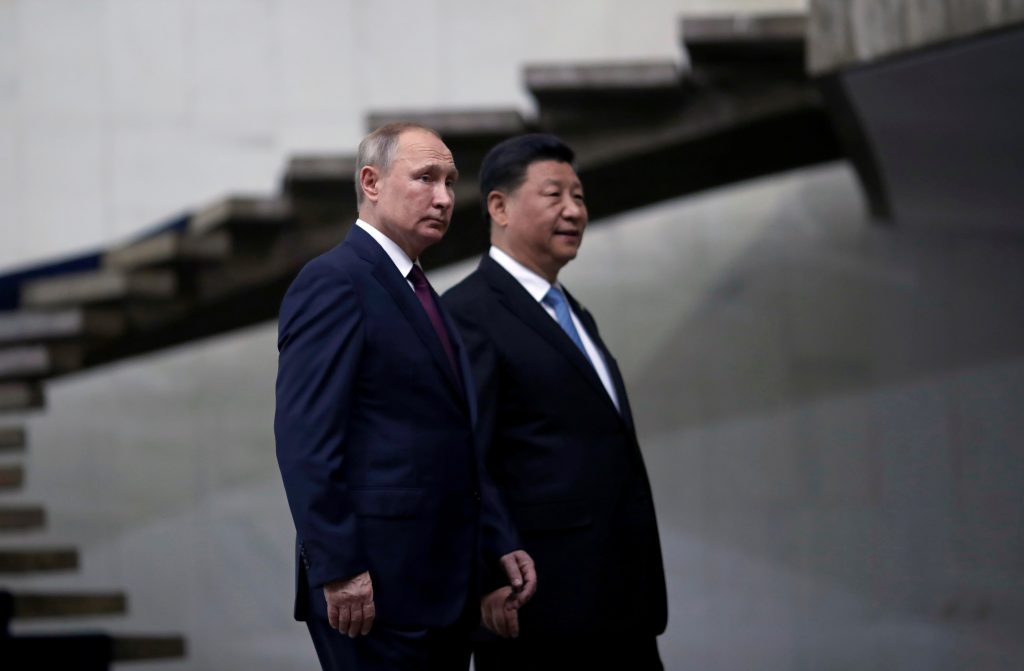

Image: Russia's President Vladimir Putin and China's Xi Jinping walk down the stairs as they arrive for the BRICS summit in Brasilia, Brazil November 14, 2019. REUTERS/Ueslei Marcelino