Dean Acheson knew a White House policy vacuum when he saw it, the absence of any Kennedy administration Berlin policy, and he was determined to fill it with the rapier brilliance that had already made him an historic figure.

His paper, the first major Kennedy administration reflection on Berlin, landed on Secretary of State Dean Rusk’s desk the day before British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan arrived in Washington. Characteristically, President Truman’s secretary of state had timed its delivery for maximum impact, laying down a hard line on Berlin at the front end of a parade of Allied visitors.

Whether a half century ago or today in 2011, those who have access to the president and enjoy his confidence, those who have strong views and a gift for communicating them, can have outsized influence at historic inflection points. That is particularly true in the early days of an administration when one is trying to steer a young, relatively inexperienced president.

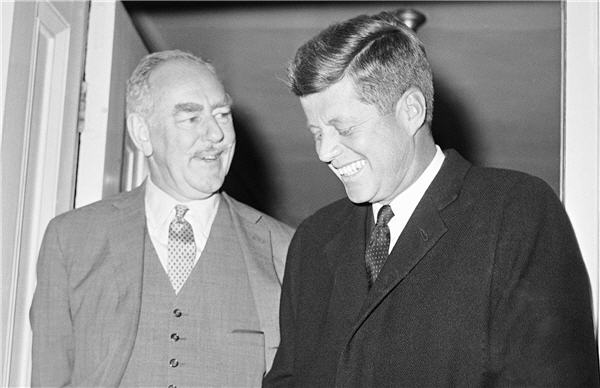

Kennedy’s recruit of Acheson as a special adviser was pleasant confirmation for him, at age sixty-eight, that his capabilities remained both relevant and required. As impeccably dressed as he was informed, he liked to tell friends that he lacked the self-doubt that so afflicted his opponents. With his bowler hat, steel-blue eyes, and upturned mustache, he would have been noticeable enough. However, he stood out all the more due to his long-legged, slender, six-foot frame.

Quick-witted and intolerant of fools, Acheson had brought to his new Berlin study the determination to outmaneuver and outmatch the Soviets that had so distinguished his career. His central argument was that Kennedy had to show a willingness to fight for Berlin if he wished to avoid Soviet domination of Europe and, after that, Asia and Africa. Wielding words like weapons, Acheson wrote that if the U.S. “accepted a communist takeover of Berlin – under whatever face-saving and delaying device – the power status in Europe would be starkly revealed and Germany, and probably France, Italy and Benelux would make the indicated adjustments.”

Not aware of Acheson’s influence, Prime Minister Macmillan was taken aback when Kennedy nodded toward Acheson during their meeting in the Oval Office on April 5, and asked him to explain why he believed a confrontation over Berlin with the Soviets was likelier than reaching an acceptable compromise solution.

With Kennedy quietly listening, Acheson listed what he called his “semi-premises:”

There was no satisfactory solution to the Berlin problem aside from resolution more broadly of Germany’s division. And it did not seem such a solution was anywhere near.

It was likely the Soviets would force the Berlin issue with the calendar year.

There was no negotiable solution Acheson could imagine that could put the West in a more favorable position regarding Berlin than it had at the moment.

Acheson’s suggestion was that the West had to hold tight to the status quo and mobilize massively and conventionally, since no one would be ready to fight a nuclear war over Berlin.

The British, however, had come to Washington instead to shift talk of military contingencies to negotiated agreements with the Soviets. Lord Home, the British foreign secretary, argued Western presence had to be put on a new legal basis as the current “right of conquest” justification for Berlin occupation was “wearing thin.”

“Perhaps,” Acheson fired back at Home, “it is our power that is wearing thin.”

The meeting broke up before Macmillan knew whether Kennedy embraced Acheson’s hard-line views. Kennedy himself wasn’t yet sure. What neither Acheson nor Macmillan knew was that Kennedy was engaged at the same time in providing the final approval for the CIA-backed invasion of Cuban exiles through the Bay of Pigs.

Its failure would change the course of the entire year.

Fred Kempe is president and CEO of the Atlantic Council. His latest book, Berlin 1961, was published May 10. This blog series originally published by Reuters. Photo: Kennedy and Acheson, Tom Fitzsimmons/AP.

Image: acheson-kennedy.jpg