Wearing a white shirt, a loosened tie, and a jacket held casually over one shoulder, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy bounded down the steps of the side entrance to the Department of Justice on Pennsylvania Avenue and extended his hand to Soviet spy Georgi Bolshakov.

“Hi, Georgi, long time no see,” the attorney general said, as if reacquainting himself with a long-lost friend, though he had met Bolshakov only briefly once, some seven years earlier. Beside Kennedy stood Ed Guthman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who had become his press officer. Guthman had arranged the unusual meeting through the man who had delivered Bolshakov by taxi and stood beside him, New York Daily News correspondent Frank Holeman.

Thus began one of the most unique and – even a half century later – only partially understood relationships of the Cold War. From that day forward, the president’s brother and Bolshakov would communicate and meet frequently – during some periods as often as two or three times monthly. It was an exchange that went almost entirely unreported and undocumented, an omission Robert Kennedy would later regret in his oral history.

He would later say that he never took notes at the meetings, and reported on them directly and only orally to his brother. Thus the Bolshakov-Kennedy exchanges could only be imperfectly reconstructed in my book Berlin 1961,working from the unsatisfying oral history at the John F. Kennedy Library, Soviet records, Bolshakov’s recollections, and the memories of several others who were involved at one point or another.

Nevertheless, during 1961 the meetings were particularly intense at the most crucial moments – before the Vienna Summit in June, ahead of the Berlin Wall’s construction in August, and finally during Nikita Khrushchev’s 22nd Communist Party Congress and the simultaneous showdown of U.S. and Soviet tanks at Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie in October.

Though Robert Kennedy expressed satisfaction about what those meetings produced, their very nature exposed the Kennedy administration to Soviet manipulation. The perils to the United States of the Bolshakov-Robert Kennedy conduit were deep. Bolshakov was little more than a message carrier from the Kremlin, who knew little about Khrushchev’s innermost thoughts. At the same time, Robert Kennedy was far less skilled at the art of deception than Bolshakov while more likely to reveal insights about his brother’s nature that might be valuable to Soviet intelligence.

It is hard to imagine two more unbalanced negotiating partners. And because President Kennedy would at first keep the contacts secret even from his own top Cabinet members, he had no independent means to verify Bolshakov’s reliability. Moscow not only controlled what Bolshakov could discuss, it also determined the precise manner in which he would raise issues. He had none of Bobby Kennedy’s license to horse trade.

The most important messages Bolshakov brought back from his first meeting with Bobby relayed the president’s readiness for a summit, his fear that the Soviet leader perceived him as weak, his aversion to negotiating Berlin’s status, and his desire above all to achieve a nuclear test ban deal.

At the same time, Bobby came back from the initial contact unable to provide his brother any greater insight into Khrushchev. He had at the same time gained the false impression that Khrushchev was ready to accept his brother’s conditions for the Vienna Summit.

After five hours of conversation, Bobby gave Bolshakov a ride home. Kept awake by adrenaline, the Soviet operative stayed up all night before cabling a full report to Moscow early the next morning. Through Bolshakov, Khrushchev knew far better what Kennedy hoped to achieve through a summit and what he most feared. At the same time, he had effectively misled the president about what the Soviet side was willing to accept.

It was perilous diplomacy.

Fred Kempe is president and CEO of the Atlantic Council. His latest book, Berlin 1961, was published May 10. This blog series originally published by Reuters.

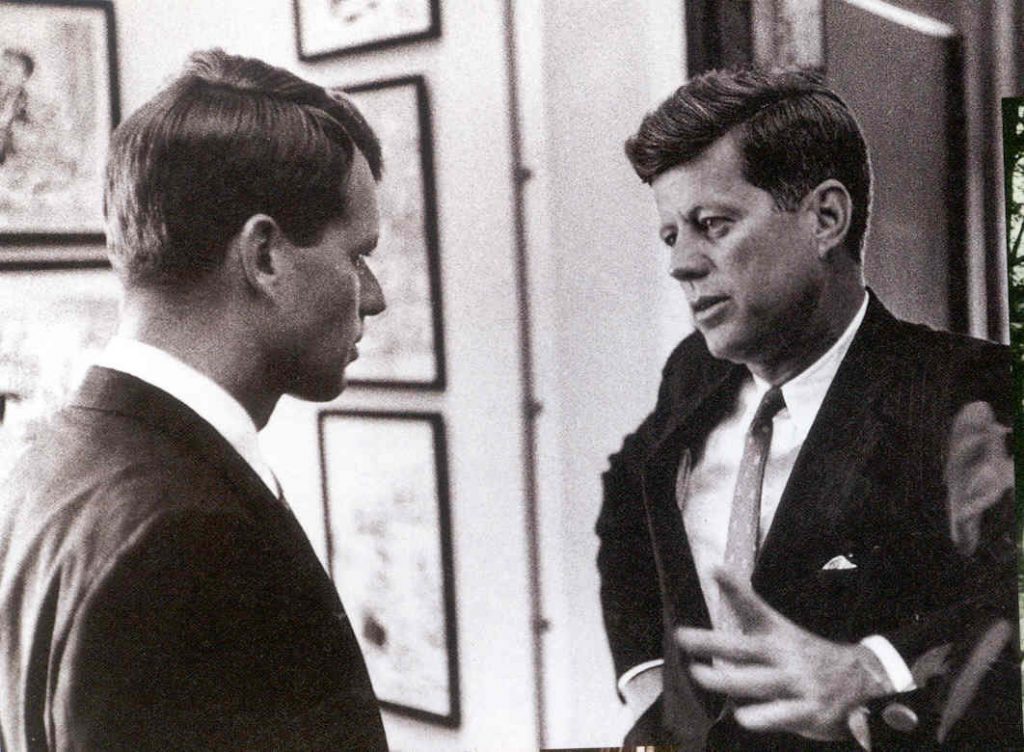

Image: rfk-jfk.jpg