NEW DELHI—On Monday, India’s ministry of external affairs warned Indians traveling through China to exercise due discretion—and pressed Chinese officials to assure Indians that they will “not be selectively targeted, arbitrarily detained, or harassed.” This warning was prompted by an incident that generated major headlines in India late last month.

On November 21, Pema Wangjom Thongdok, a UK-based Indian citizen, was detained for eighteen hours at Shanghai Pudong airport while in transit to Japan. According to Thongdok, it was a transit she had made a year earlier, and she had confirmed with the Chinese Embassy in London that she didn’t need a transit visa.

Thongdok was detained because her passport lists Arunachal Pradesh as her state of birth. Multiple Chinese immigration officials told her that her passport is invalid and that she is Chinese, not Indian. China claims Arunachal Pradesh, which Beijing calls “South Tibet.” Since a Chinese attack on the state that provoked a 1962 war, Arunachal Pradesh has been a constant source of bilateral tensions between China and India. Indian citizens of the state are given stapled visas by Beijing and sometimes denied visas altogether. On November 25, India’s external affairs ministry released a sharply worded statement about Thongdok’s travails. Arunachal Pradesh “is an integral and inalienable part of India,” it declared, “and this is a self-evident fact. No amount of denial by the Chinese side is going to change this indisputable reality.”

The incident was jarring because relations between India and China—two longstanding competitors—have been relatively stable for over a year, with both countries having taken a series of steps to ease tensions. The Thongdok incident should be seen not as a threat to the India-China détente, but as a reminder of the détente’s limits. India and China are bitter rivals and destined to remain so for the foreseeable future.

A delicate détente

In October 2024, India and China signed a deal that resumed border patrols in a region where a deadly clash had occurred in 2020—the worst between the two since the 1962 war. The agreement was a confidence-building measure that set in motion a series of conciliatory moves.

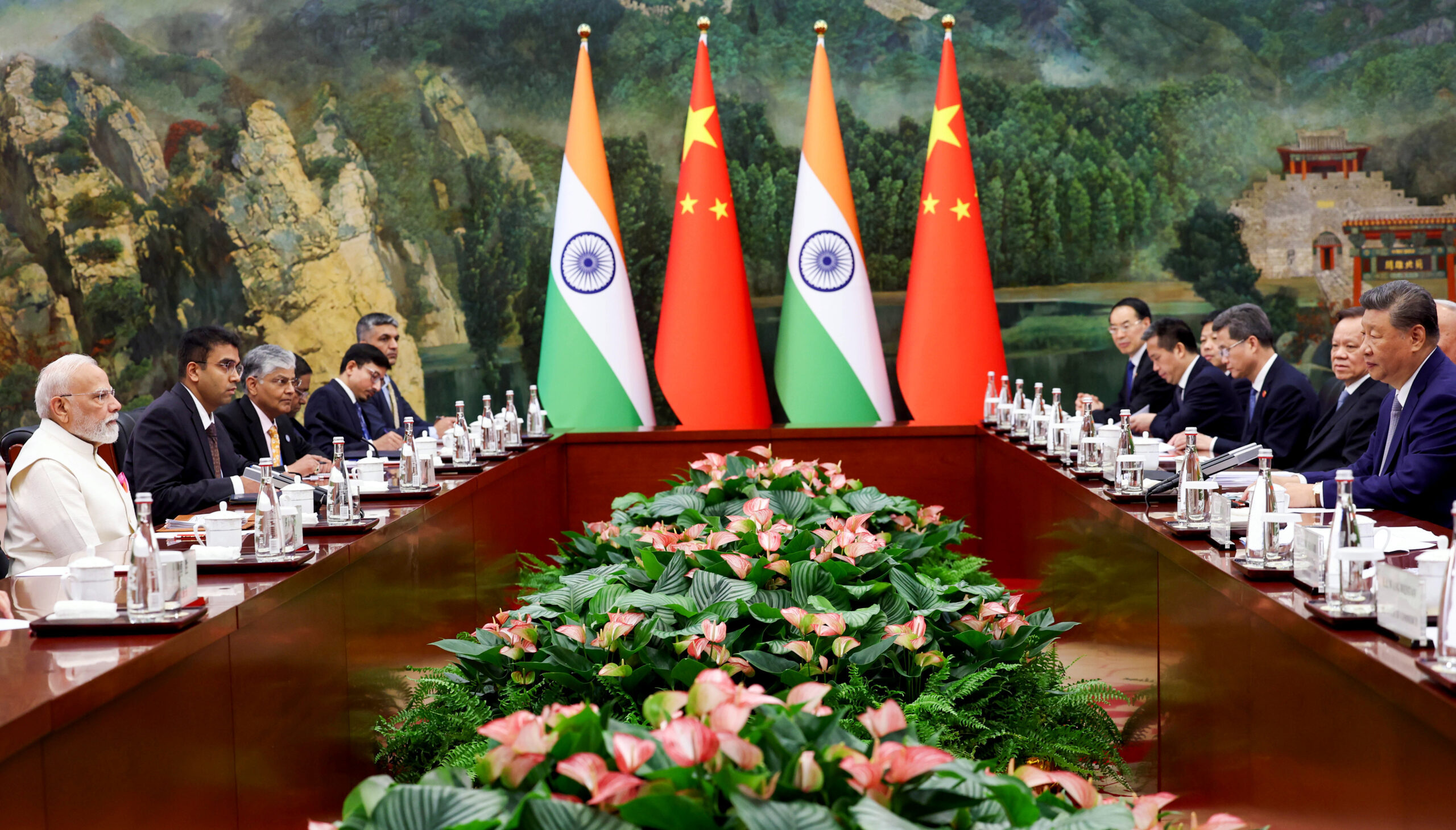

In August, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi traveled to China—his first visit in seven years—to participate in a regional summit and meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping. The earlier border deal likely gave Modi the diplomatic and political space to make the visit. But New Delhi’s rising tensions with the Trump administration, provoked in part by the 50 percent tariffs the United States slapped on India in August, gave him an even stronger incentive to make the trip. Recent US policies have also provided New Delhi with strong motivation to explore expanding its already robust commercial partnership with Beijing.

In October, direct flights between India and China resumed after a five-year suspension. And just last week, China’s consul general in Kolkata wrote about the bilateral partnership’s potential in an op-ed for the Indian Express.

Persistent sources of tension

India and China do see eye to eye on some issues, including the threat of Islamist terrorism and support for a multipolar international order. And they are both members of organizations, such as the BRICS grouping and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, that aim to counter the West.

But there has always been something a bit awkward about the two countries’ public displays of comity. Ultimately, they are natural rivals and not capable of—nor desirous of—full-scale reconciliation. India and China are two massive, proud, civilizational states. They share a 2,100-mile-long rugged border, and along that border fifty thousand square miles—an area roughly the size of Greece—are disputed. China has a deep alliance with Pakistan at a moment when India-Pakistan relations are tenser than they’ve been in decades. In May, India and Pakistan engaged in their most serious military conflict since 1971. During that conflict, Pakistan, for the first time, deployed Chinese weaponry and technology against India in combat. Meanwhile, India hosts the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet, whom China regards as a dangerous separatist. India is also deepening ties with Taiwan, which Beijing regards as a renegade province.

Additionally, New Delhi has walked back some earlier signaling about wanting to loosen restrictions on new Chinese foreign direct investment in India, which was halted after the 2020 border clash. In April, Indian Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal declared that this economic opening is not happening. And for all the talk of a robust commercial partnership, that aspect of India-China relations is also riven with tensions. Chinese financial services, fintech, and pharmaceuticals face significant scrutiny in India due to data-security concerns. Similarly, concerns over surveillance capabilities have led to stringent security rules in the CCTV market, where over a million cameras in government institutions used Chinese technology as of 2021. This is especially concerning given reports that highlight the risks of leaked CCTV footage. Despite all of this, Chinese consumer technology still dominates in India—for example, making up eight out of the top ten smartphone brands. Additionally, the Chinese electric-vehicle manufacturer BYD is expanding rapidly in India.

Don’t mistake India’s hedging for reconciliation with China

This all helps explain why the next flare-up between India and China is just around the corner, and how efforts to ease tensions can only go so far. Even over a year of relatively cordial ties, India has never stopped treating China as a competitor. Last month, India agreed to a trilateral technology and innovation accord with Canada and Australia that is clearly meant to counter China’s deep global influence over tech supply chains and innovation. New Delhi remains a fervent backer of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue—a partnership comprising India, the United States, Japan, and Australia—which is all about countering China in the Indo-Pacific. And India’s support for this partnership remains strong even as tensions with Washington have set back its progress. India also has continued to negotiate deals to supply Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam with supersonic missiles meant to counter Chinese aggression in the South China Sea. Manila has already received initial shipments, and deals are expected to soon be finalized with Jakarta and Hanoi.

One of the biggest foreign policy developments during our travels in India was Russian President Vladimir Putin’s December 4-5 visit to New Delhi. He came at a moment when India’s deep partnership with Russia has been experiencing some shakiness, in part because of a Russian war in Ukraine that India has said should end. And a big reason why India opposes the war is that it has brought Moscow closer to Beijing.

In the early days of the second Trump administration, Indian scholars, former officials, and other foreign policy specialists, in conversations with one of the authors, expressed concerns about the possibility of the Trump administration seeking some type of understanding with China. At first blush, it was a curious concern to voice, given that India itself was at that time actively working to ease tensions with Beijing. But what these Indian analysts were really worried about is that the United States could seriously consider reconciling with China, meaning a decision to end US competition with Beijing and forge a friendly relationship—something that is not on the table for India.

Ultimately, India has moved to ease tensions with China to reduce dangers on its border, and more broadly to make the relationship more stable. These moves come at a moment when it can ill afford another crisis with Beijing—not with tensions dangerously high with Pakistan, and not with the unexpected strains in its relations with Washington. It’s essentially a hedging strategy to help India get through an especially turbulent geopolitical moment. It should not be mistaken for a full-scale rapprochement with Beijing.

There’s a lesson here for US-India relations. It’s unclear whether US President Donald Trump will push for reconciliation with China in the run-up to or during his planned trip to Beijing next April. But if he does not seek rapprochement with China, then the strategic rationale for the US-India partnership—a shared desire to counter China—will remain intact, helping the two countries’ bilateral ties bounce back if they can work through their current tensions.