WASHINGTON—In less than a week, Greenland has moved from being an existential crisis for NATO to a more mundane challenge of negotiating an agreement, following the news on January 21 of a “framework” deal between US President Donald Trump and NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte. But the details of the agreement will still be critical to the future of the Alliance.

The final result will depend on a common understanding of the security requirements that the United States and its NATO allies have both for Greenland and for the Arctic more generally, as well as political and legal considerations.

NATO’s Arctic security requirements most importantly derive from dealing with the threat posed by Russia. As the Pentagon’s 2024 Arctic Strategy stated, “Russia also has a clear avenue of approach to the U.S. homeland through the Arctic and could use its Arctic-based capabilities to threaten the ability of the United States to project power both to Europe and the Indo-Pacific region, constraining our ability to respond to crises.” The threat from a “clear avenue of approach” is not only to the United States, of course, but also to Norway, Finland, the United Kingdom, Iceland, Denmark, and Greenland itself, and the general power projection threat from Russia obviously implicates all of NATO. China has its own designs in this region, even though none of its territory borders the Arctic Ocean. This is not only a concern for Europe and the United States; it is also something that gives Russia pause.

To meet these challenges, NATO has discussed the possibility of an Arctic Sentry mission somewhat comparable to the recent Baltic Sentry mission established this past January, after Russian and Chinese disruptions of undersea cables in the Baltic Sea. An Arctic Sentry mission would be much more extensive than the Baltic Sea effort and would include shared responsibilities drawing on US, Canadian, and European efforts. In a division of labor, under the NATO framework, the United States could focus on the defense of Greenland and the surrounding environs.

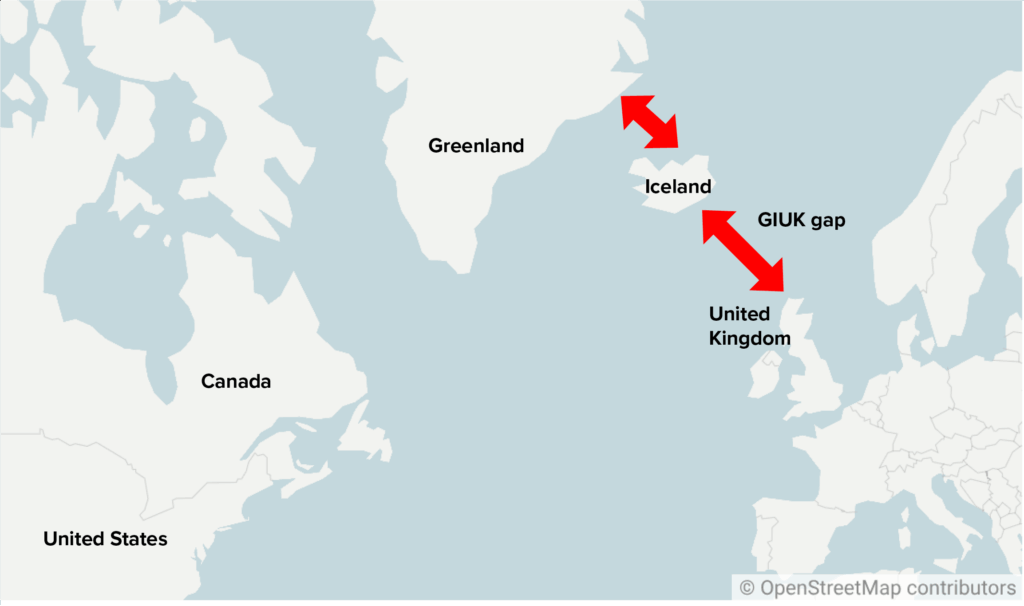

That would require additional airfields; expanded naval facilities; integrated air and missile defense, including requirements for the Golden Dome program; facilities for unmanned vehicles, including those relevant to maritime surveillance and sea control; and surveillance capabilities both for the Arctic and those relevant to the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) gap. Canada and Europe could provide complementary capabilities, including increased air and naval capabilities for maritime domain awareness and, in wartime, control of the seas, including the GIUK gap, to keep Russian naval forces—particularly submarines—out of the North Atlantic.

Options for an agreement

An Arctic Sentry mission would add up to a much-expanded US presence in Greenland, perhaps larger than its Cold War presence of ten thousand personnel and thirteen bases, plus a number of smaller facilities. To accomplish that result, the United States and Denmark will have to come to an agreement—including the government of Greenland both because the activity would take place on its territory and because applicable agreements between Denmark and Greenland provide that Greenland could become an independent country by popular referendum.

How might this agreement be reached? It is possible that the existing 1951 United States-Denmark agreement could provide the “framework” that the president referenced after his meeting with Rutte. But in the run-up to this past week’s meeting in Davos, the Trump administration suggested that the 1951 agreement did not provide the degree of control over assets and installations that the United States needed. Moreover, the agreement lacks any discussion of control of operational arrangements as does, for example, the US-Canada NORAD agreement. Operational control of the forces will be most important for an effective defense.

Another suggested solution has been for the United States to establish a “compact of free association” with Greenland as it has with several island nations in the Pacific whereby the United States essentially provides security and defense while the islands remain sovereign and independent in all other respects. The fundamental obstacle to this approach in the Greenland context is that Greenlanders currently do not want to be under US control and, in any event, such an agreement would require Greenland to in fact be an independent nation, which it currently is not.

A third proposed solution is to parallel the United Kingdom’s arrangements with Cyprus, where it maintains two bases. However, the United Kingdom has full sovereignty over those bases, and it seems unlikely that either Denmark or Greenland would be willing to accept such an approach.

A “shared responsibility and shared sovereignty” approach

Fortunately, there is an alternative way to establish an effective framework of shared security responsibility—using the concept of “shared sovereignty”—that can turn the Trump-Rutte framework into reality and fully meet the requirements of all parties.

“Shared sovereignty” in international law is an arrangement among governments that authorizes the engagement of external actors in what normally would be the domestic authority structures of a host government. European nations have undertaken several such arrangements—including the European Union (EU)—in which new authorities displace the role of national governments in certain areas. And beyond the EU, there are other historical examples of shared sovereignty in the European context. The Federal Republic of Germany, for example, prior to German reunification, limited its sovereign control over its armed forces, integrating them into NATO, renouncing the right to produce chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, and giving Western powers the right to declare an emergency in response to a threat to security.

In more limited contexts of shared sovereignty, Lake Constance operates collaboratively on undefined borders among Switzerland, Germany, and Austria; Pheasant Island is administered each year by Spain between February 1 and July 31 and by France between August 1 and January 31; and until the independence of Vanuatu in 1980, the island was under the joint sovereignty of France and the United Kingdom.

The United States has also had arrangements similar to shared sovereignty, including the original agreements over the Panama Canal and the ongoing control of the Guantanamo naval base in Cuba.

Europe has even recently undertaken a shared sovereignty arrangement for similar security reasons as have been raised by the United States in the context of Greenland. The United Kingdom and Mauritius signed an agreement in May 2025 that, while transferring overall sovereignty of the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean to Mauritius, nonetheless provides for the “rights and authorities [over the island of Diego Garcia] that the United Kingdom requires for the long-term, secure and effective operation of the [military] Base.” The UK secretary of defense has said the agreement achieves the “secured unrestricted access to, and use of, the base, as well as control over movement of all persons and all goods on the base and control of all communication and electronic systems.”

Diego Garcia is home to an airfield, a deep-water port, advanced communications, surveillance capabilities, antennas and monitoring support for the global operation of GPS, capabilities for “Deep Space Surveillance,” and Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban monitoring equipment. These capabilities overlap with those important for ensuring the security of Greenland.

The Diego Garcia agreement has been greeted with support by the United Kingdom’s “Five Eyes” partners—the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—along with others including Japan, India, and the African Union. In May 2025, the US State Department said the agreement “secures the long-term, stable, and effective operation of the joint US-UK military facility at Diego Garcia,” adding that president “expressed his support for this monumental achievement” to British Prime Minister Keir Starmer.

To be sure, more recently the president called the agreement an act of “great stupidity.” But his criticism was of the United Kingdom giving away certain broader elements of control. In the Greenland context, shared responsibility and shared sovereignty along the lines of the Diego Garcia agreement could provide the United States the kind of control that the president has said he deems critical to meeting US and NATO security requirements. But it would not go so far as denying Denmark’s and Greenland’s own aspects of sovereignty, which are particularly relevant in the economic context of their relationship with the European Union and in the authority of Greenland to declare independence by referendum.

How to get to a deal

So far, Denmark has asserted an unwillingness to negotiate regarding any aspects of sovereignty. It must be noted, however, that this position is in contradiction both to its joining the European Union and to its own agreement allowing Greenland to become an independent nation by referendum.

The broader point is that sovereign states, in the exercise of that sovereignty, decide all the time to limit or “share” that sovereignty when it serves their national interests—and remain sovereign after doing so. Such would be the case with a Diego Garcia approach to Greenland. A shared responsibility and shared sovereignty agreement with the United States and NATO would advance the interests of Denmark in a secure Greenland and a more secure Denmark. It would provide for a highly effective defense of both Greenland and the Arctic.

To operationalize this approach, the United States would need to identify the security capabilities it requires. Then a determination can be made as to the amount and placement of facilities to support such efforts. Relevant areas for those facilities could be identified, and for those areas the United States could be given the degree of shared sovereignty that provides it full control—much as the United Kingdom has full control over Diego Garcia. The United States would pay the costs for these facilities, which would be substantial and would require years to implement. The term of the agreement could be quite extensive; for Diego Garcia, the term is ninety-nine years—but it could even provide for a “perpetual lease,” which would have no termination date. The agreement should also include provisions prohibiting Russian or Chinese engagement on the island.