WASHINGTON—US President Donald Trump just made one of the most consequential decisions of his presidency—one that will impact the global economy long after he leaves office. To Trump, the selection of a Federal Reserve chair is the ultimate mulligan. It’s a chance to fix what he sees as one of the worst decisions of his first term, the selection of Jerome Powell as Fed chair.

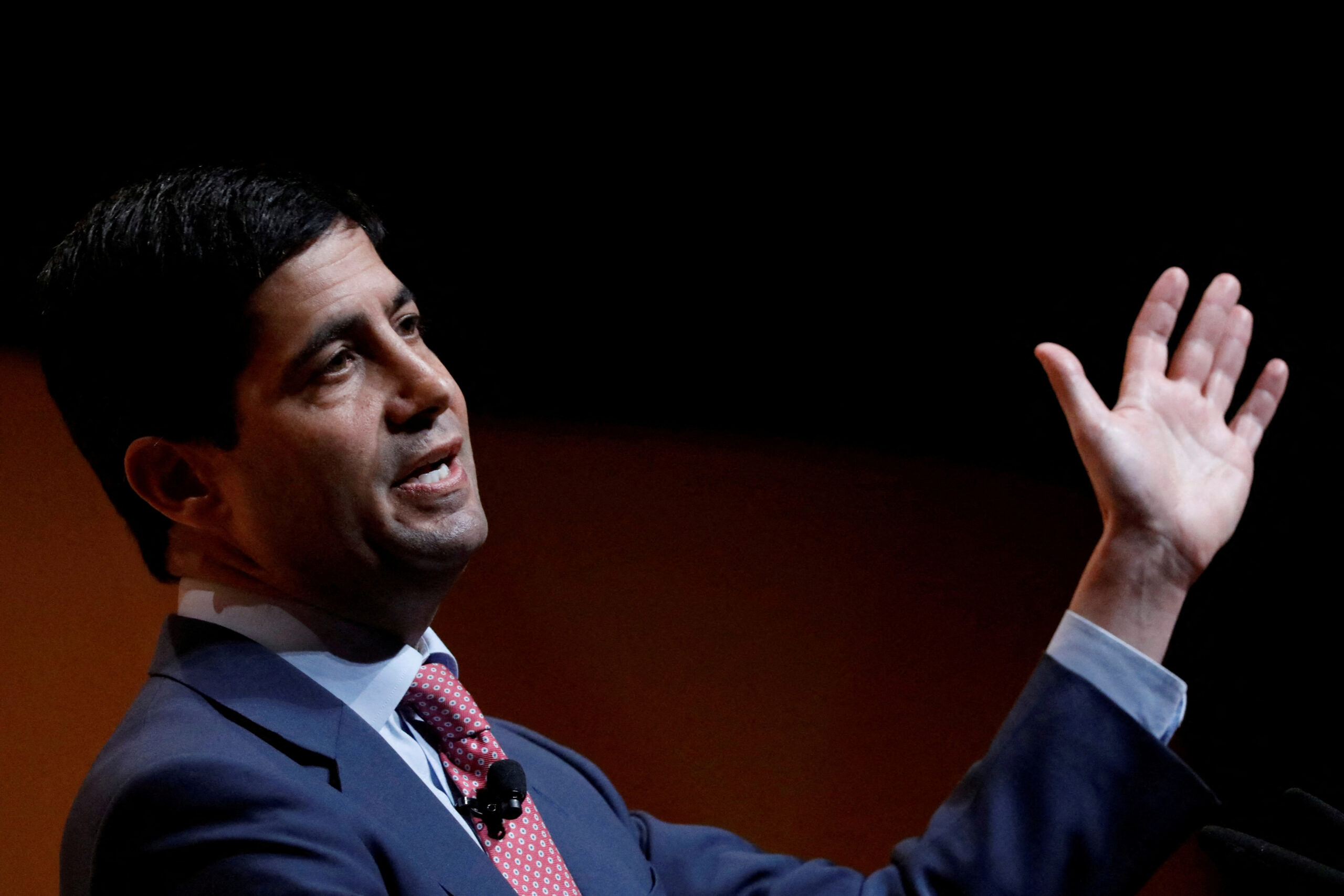

At first glance, Powell and Kevin Warsh, whom Trump announced on Friday morning as his nominee, are strikingly similar. Both are former Fed governors, both are lawyers (not economists), both worked for Republican presidents (Warsh for George W. Bush and Powell for George H.W. Bush), and both made their careers on Wall Street. But that’s where the similarities end.

The most important part of Warsh’s selection has nothing to do with monetary policy (even though that’s the single factor Trump has said was most important in his decision). Warsh has been vocal for years about what he sees as the Fed exceeding its mandate and using a range of expanding tools outside setting interest rates, including buying bonds and mortgage-backed securities. These tools are referred to as quantitative easing and have grown massively over the past fifteen years in the wake of the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Warsh believes the Fed has distorted the healthy functioning of the US economy through its injections of money into the market, helped assets on Wall Street at the expense of Main Street, and taken on the role of implementing fiscal policy.

Guess who else thinks exactly the same thing? Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. In fact, Bessent wrote an article last year about Fed overreach that was closely read across Wall Street and inside the White House. Bessent and Warsh are completely in sync on the need to limit the Fed’s use of unconventional tools, and this could lead to a significant change and scaling back in the way the Fed does its work in the years to come. Donald Trump got his man—but Scott Bessent did as well.

What does this mean for the global economy? If you’re a country looking to the Fed to jump into the fray during an economic crisis, you may be in for a rude awakening. This is not going to be the “committee to save the world” Fed of Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, and Jay Powell. Warsh has said before that it is the US Treasury and Congress that should act first in a crisis—not the Fed. Warsh’s Fed will be a narrowly focused one, and that means the next moment of stress for the global economy might unfold very differently with him at the helm.

On monetary policy, Warsh seems like a curious choice for a president determined to get lower interest rates. During his previous tenure as governor from 2006 to 2011, he was considered one of the most hawkish members of the committee on fighting inflation. In fact, in April 2009, in the depths of the global financial crisis—when inflation was just 0.8 percent and unemployment was at 9 percent—he said he was concerned about high inflation. (I was working at the White House at the time, and I remember those comments standing out.) He was clearly out of consensus with his then-colleagues at the Fed.

The prevailing wisdom is that Warsh has changed his views since then and now is focused on the artificial intelligence-induced productivity boom, which he says means rates can be lower than they otherwise would be. It’s also fair to ask whether his more dovish comments are meant to appeal to Trump’s well-known preferences. But whether the dovish talk holds throughout his tenure remains to be seen. Bond markets are similarly skeptical, with yields rising several weeks ago when his name returned to the top of the list. Given his views on reducing the Fed’s balance sheet and at least the potential for him to be a slightly more hawkish chair than Trump’s other options would have been, expect to see mortgage rates going higher this week—precisely the opposite of what Trump and his economic team have wanted going into the midterm elections.

But don’t mistake higher bond yields for market skepticism over Warsh himself. Wall Street will breathe a small sigh of relief. Whatever his views on the balance sheet and Fed overreach, Warsh is a relatively conventional pick—especially given some of the other names that were in the running. He is from Wall Street, a former Fed governor, and well known both in Washington and New York. Ultimately, markets believe he is someone they can trust with the most important economic policymaking job in the world. And in the end, that may be one of the most meaningful signals from this selection: It appears that market forces—as we were reminded after the “Liberation Day” tariff announcement and just last week over Greenland—may be the most potent constraint on the Trump presidency.

Warsh will likely be confirmed by the Senate and take up his role in May. He will have to prove to markets that central bank independence is core to his chairmanship. The first test might come as soon as the summer, when tariffs may keep inflation somewhat sticky, a divided Fed committee may want to keep rates steady, and Trump will expect his new chair to deliver.