WASHINGTON—The Trump administration provided quite the welcome-to-2026 jolt with its ouster of Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro. Many US analysts view the move as benefiting the United States at China’s expense, since Beijing had backed Maduro and his predecessor Hugo Chávez to gain access to Venezuela’s oil. But the reality is more complex.

That relationship wasn’t paying off as well as Beijing had hoped, but it was sticky—there was no easy way for Beijing to extricate itself from Venezuela’s cratering economy or the reputational damage it was incurring over its support for Maduro. So Chinese leaders were staying the course. Now, however, the Trump administration has put another option on the table: China can evade responsibility for anything that goes wrong in Venezuela, since Washington now owns that problem. Moreover, Beijing can portray itself as the more responsible partner to Venezuela’s neighbors, all while maintaining access to Venezuelan oil. That’s a pretty good outcome for Beijing.

Two big factors make this less of a win for the United States—and less of a loss for China—than many analysts realize.

An oil boom won’t come easy

First, there is a big difference between oil reserves and oil production. Venezuela does have large oil reserves. But bringing them to market is complex. Venezuelan oil is a heavy, sticky crude that is expensive to extract and requires specialized refining.

China has refineries set up to process it. But Venezuelan exports never reached the heights Beijing had hoped for. The Venezuelan military manages the nation’s state-run oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., or PDVSA. That management has been less than stellar. Despite the nation’s immense reserves, Venezuela’s oil exports went into a nose-dive about a decade ago due to mismanagement in an era of declining oil prices. Those exports still haven’t recovered to previous highs. When China first began signing deals with Venezuela in the mid-2000s, the nation was producing around two million barrels of crude oil per day. Given the nation’s reserves, Beijing had high hopes for growth on that output. Instead, at year-end 2025, Venezuela’s strongest production was only around 900,000 barrels per day. That is nowhere near the big leagues. On Venezuela’s best day in 2025, for example, it produced less than one fourth of the crude oil coming out of China—and less than one fifth of the crude coming out of Texas. Oil accounts for around 18 percent of China’s energy consumption, and only 4-8 percent of that (depending on the day) comes from Venezuela.

To be sure, as long as it was sanctioned, Venezuelan oil was extra cheap, and Beijing was not going to walk away from cheap oil that it had already paid for via earlier loans to Caracas. But this relationship was nowhere near an energy supply game-changer for Beijing.

President Donald Trump appears to assume that US oil majors will walk in and turn this around. On January 3, he said, “We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country.” But the nation’s oil sector is a mess. Restoring production to pre-Chávez levels is, at best, a one-to-two decade project. And China has already tried to do just that: It poured in billions of dollars and sent in its own oil companies (which are very good at operating in risky environments). Exports still declined.

There is a lot of confusion around exactly how much money Beijing has poured into Venezuela and exactly how much Venezuela has paid back via oil shipments. Those transactions are often nontransparent by design. The best estimates are that China provided around sixty billion dollars in official government-to-government loans, and around a hundred billion dollars in total when all Chinese investments in the nation are included. The thing is, Venezuela has just about paid that all back, because it paid in oil, and the oil kept flowing, albeit never at the levels Beijing was hoping for. The best estimates are that Venezuela currently owes Beijing around ten billion dollars to fifteen billion dollars in remaining oil shipments. Even if China gets nothing else, it is not exactly walking away empty handed, particularly given that much of that oil shipped at rock-bottom prices. It could be that Beijing is offloading a declining asset at an opportune time.

China may be dodging a quagmire

The second big factor that complicates this picture: Venezuela itself. The country’s future is uncertain, and its economy is heavily dependent on oil production, which is faltering. It is not yet clear who in Venezuela will have political legitimacy when the United States retreats. From a diplomatic perspective, until January 3 this was Beijing’s mess to deal with. China supported Maduro despite the fact that all evidence pointed to him losing the last election. That support was an albatross around Beijing’s neck across the region. China wants to be seen as Latin America’s preferred economic partner, but that argument is hard to make when your biggest debtor is barely functioning economically and lost support politically, as demonstrated when Maduro falsely claimed victory and hung on to power after losing the last election. The United States has taken this challenge out of China’s hands. Now, whatever goes wrong in Venezuela, China can blame it on Washington.

China also appears eager to use this incident to paint the United States as a disruptor and a bully, in keeping with its longstanding characterization of Washington as a hypocrite when it comes to the rules-based order. That carefully crafted narrative is designed to give Beijing a free pass when it violates international rules and norms, which it does on a regular basis.

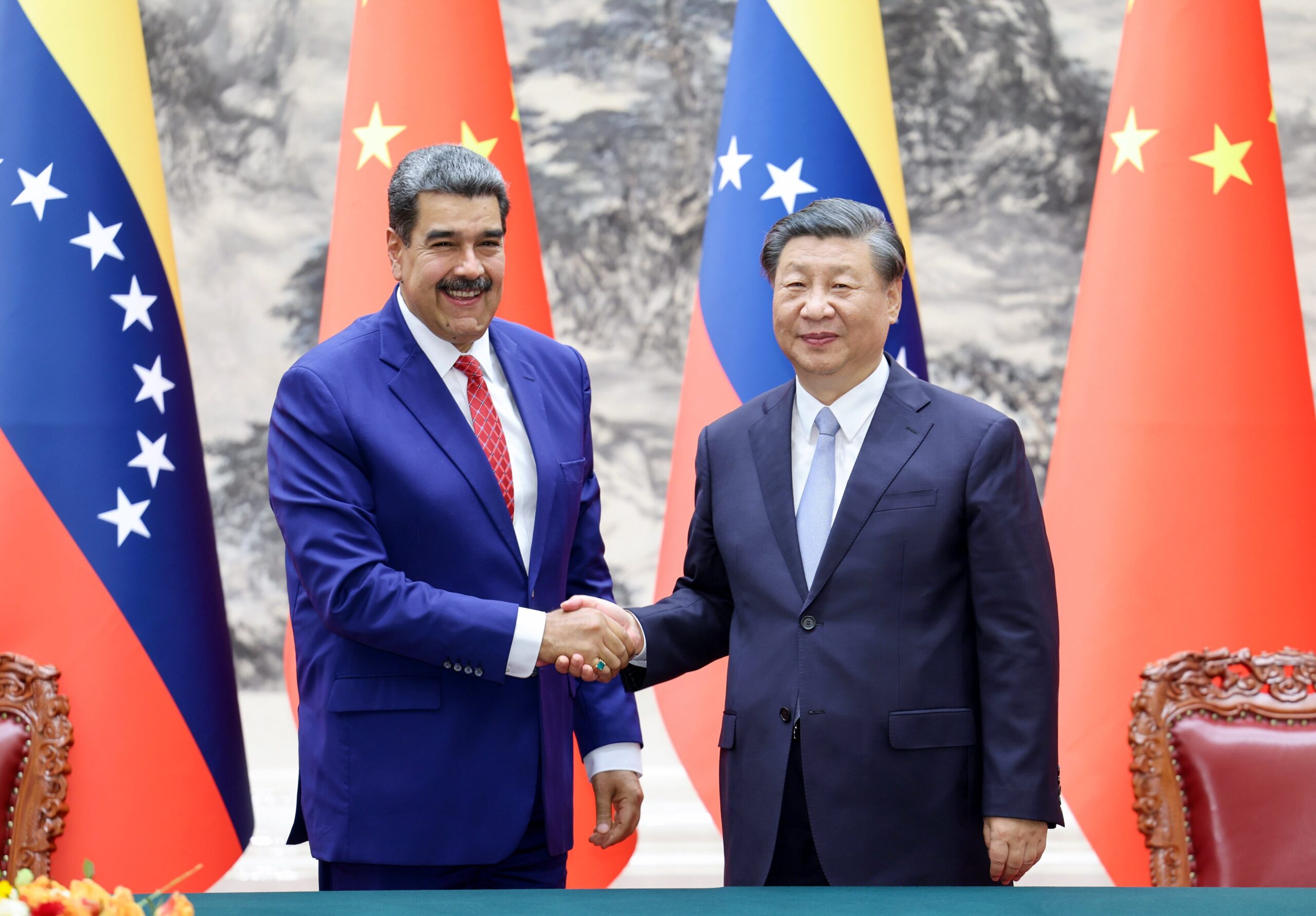

On Monday, Chinese President Xi Jinping stated that “unilateral and bullying acts are dealing a serious blow to the international order.” China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency called the United States “the blatant violator” and published a cartoon image of Lady Liberty surrounded by burning oil cans, stomping on “international law” and “national sovereignty.” Beijing may view the narrative fodder it gains from the US move as well worth forfeiting the oil shipments it has not yet received from Venezuela.

For the most part, China has not spent any real political capital to push back against the US action. Instead, Beijing is keeping its close diplomatic ties to the regime and mostly letting things play out—while voicing complaints here and there—to see how it might benefit. Some Chinese observers appear to think the United States is walking into a quagmire that will keep Washington tied up (and out of China’s way) for decades.

Hu Xijin, a popular Chinese commentator who formerly served as editor-in-chief of the nationalistic Global Times and has more than twenty million followers on Weibo, is a case in point. He recently stated that “it’s very likely that Venezuela will be more expensive than Afghanistan” and “Trump’s arrest of Maduro is tantamount to making a promise that the United States will be responsible for Venezuela’s democratic prosperity to the end.” China should know just how expensive bailing out Venezuela will be, given that it already spent around one hundred billion dollars on that project.

Perhaps the worst case for Beijing is that it does not get any more oil out of Venezuela, but it successfully offloads a declining asset. Chinese leaders are likely thinking that they may get the oil anyway. Trump has stated that he plans to keep the oil flowing to Venezuela’s current buyers, including China. If that does occur, if the United States does step up to the plate to pour billions into Venezuela’s oil sector and a good portion of that oil goes to China, then this could be Beijing’s best chance at actually recouping the remaining balance on some of its earlier investments. That is not exactly a bad deal for China. But for Washington, it is not at all clear where this ends up, or how many billions this project will consume. Washington may find itself carrying the same albatross that China just offloaded.