China must spread its wealth to reach equality

Table of contents

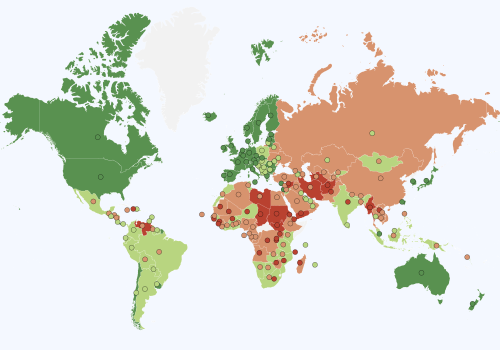

Evolution of freedom

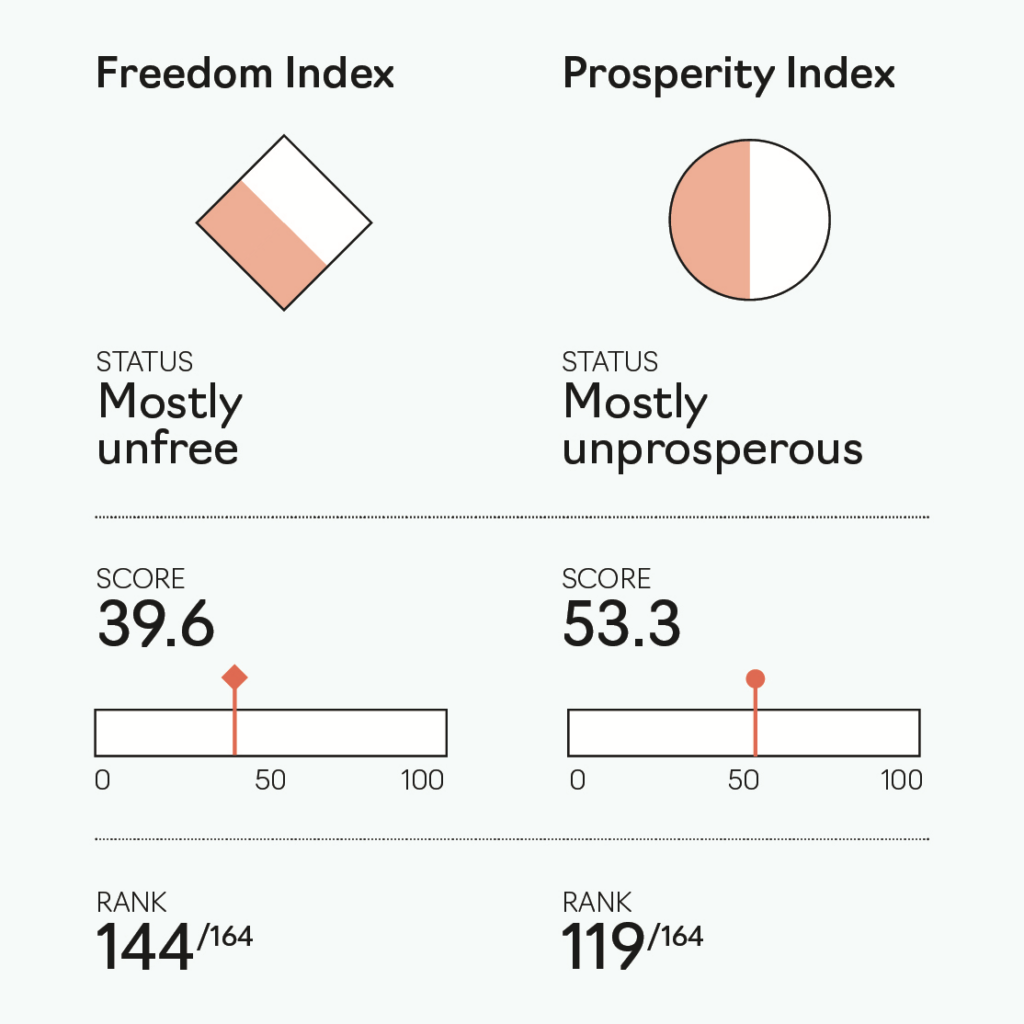

Examining the Freedom Index overall, which combines economic, political, and legal freedom subindexes, the differences between China and the rest of the region are striking: not only does China underperform compared to the regional average (in 1995, the beginning of the Index, China’s freedom score was just over 40 compared with just under 60 for the East Asia & the Pacific regional average) but it shows an overall decline in freedom over the Index time span. Overall freedom improved slightly between 2000 and 2009, but since President Xi Jinping took office in 2013, it has been slowly declining.

Consideration of freedoms in China needs to be put in some context, since much of the movement on the Freedom Indexes reflects tensions between the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) efforts to promote economic growth and its need to manage social dissent. The first decade of this century saw an intense focus on economic growth in China, in which the government undertook significant and rapid economic reforms to liberalize the economy. For example, prior to these reforms practically all Chinese industries were state-owned. Chinese leaders realized the economic gains to be made from privatizing China’s industries and enabling foreign joint ventures. China’s admission to the World Trade Organization in 2001 provided another huge economic boost. The country’s export-driven economic development flourished because of its preferred trading status with—and then integration into—most of the major world economies.

The first period on the graph, from 1995 to roughly 2010, which shows gradual improvement on the Freedom Index, tracks closely with this period of economic growth. State control over citizens’ private lives decreased, while many citizens experienced dramatically improved standards of living. In stark contrast to an earlier era of state-controlled housing assignments and goods allocations, everything from housing to basic commodities to healthcare became available in commercial markets.

Chinese civil society, which had not really existed before 2000, began to expand during this time as well. From the time of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1947, citizens and government operated under a system of social management known as “the iron rice bowl,” under which the CCP and the government provided for all of the needs of citizens from cradle to grave, and also controlled all aspects of people’s lives. As a result, throughout most of the 1990s, there were virtually no nongovernmental organizations operating in China. However, around 2001, China’s economic liberalization began to affect the country in multiple ways. Economic success and prosperity empowered Chinese citizens with more access to information. Citizens became more confident in themselves and less reliant on the government as they began to realize that the government either was not taking care of, or could not take care of, all their needs. Chinese civil society organizations (CSOs) emerged in part because the government’s promise of the “iron rice bowl” became impossible to fulfill; these CSOs became a channel for people to both voice their discontent and develop solutions to the challenges they faced.

Between 2000 and 2008 was a dynamic period, especially in terms of civil society. People began to voice their needs, priorities, and grievances, pushing back against the party’s controls. During this time, though the CCP ostensibly controlled nearly every aspect of life, the system allowed for some experimentation. Local officials, tasked with achieving ambitious economic targets while maintaining social order, and beyond the scrutiny of the center, realized they had considerable room for flexibility. For nearly a decade, local officials experimented with a range of approaches, such as increasing women’s participation in politics, participatory budgeting and other types of local governance reform, and opening limited space for public advocacy on some issues. This was no golden age: restrictions persisted and controls were particularly oppressive for China’s ethnic minorities and people living in Tibet and Xinjiang. However, the period marked a gradual increase in overall freedom in China. It corresponded with a time when ordinary Chinese citizens had a greater say in decisions affecting their daily lives. Civil society activity combined with local governments’ eagerness to deliver economic targets created space in which people could associate, voice their concerns, and even actively seek redress from the government, such as compensation for losses in land disputes.

Around 2008–09, a number of events were precursors to a significant shift in the CCP’s approach that had an impact on political freedoms: the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, the Beijing Olympics, and an impending change in the senior leadership of the party. While the party continued to prioritize economic growth, its actions indicated an intention to limit growth and openness to only that sector, and to reassert party control of the social and political space, particularly at the grassroots level. Post-Olympics, there was a noticeable decline in enthusiasm for direct external influence in China. Avenues for free expression and civil society began to systematically close, and new laws restricting civil society activities emerged.

Overall, it is striking how, despite massive economic advancement, China achieved very little progress in overall freedom during this period. When these data are compared to the East Asia & the Pacific regional average, China’s performance is truly underwhelming. The CCP missed the opportunity to leverage China’s economic growth to bring substantial improvements in the lives of its people and across various indices.

The Index shows a very modest aggregate increase in economic freedom from 1996 to 2022. Economic freedoms increased quite dramatically from about 2002 to 2008. The relatively higher score on economic freedoms in China, compared to political and legal freedoms, corresponds with the government’s focus on economic development during this period, as described above, and the challenge faced by the CCP in maintaining its previous systems of control. As noted earlier, the privatization of state-owned industries, combined with newly opened commercial markets, provided Chinese citizens with a range of choices not previously available to them. Other factors contributing to the positive trend during this period included the protection of property rights and an increase in women’s economic freedom. Two things are striking in the data: First, after a sharp decline in overall economic freedom around 2009–10 (corresponding with the global financial crisis), economic freedoms did not reemerge—even as the Chinese economy grew to be the second largest in the world after 2010; Second, three of the four economic freedom trend lines remained quite static for several years after about 2004. Despite astounding economic growth, there was no significant subsequent change in the trajectory of economic freedom. This lack of progress is indeed noteworthy.

In terms of political freedom, China starts on a lower score than for economic freedom, then remains relatively static until a sharp and consistent decline after Xi Jinping assumed power in 2013. It is worth noting the trends among the four indicators of the political freedom score; until about 2005, they each remain static or show modest improvements. After 2005, only legislative constraints on the executive improves while the other scores decline, civil liberties and political rights dramatically so. These trends again reflect the CCP’s manipulation of citizens’ rights to serve the party’s broader need for social control. As economic growth accelerated from the mid-1990s, the central government faced challenges in fulfilling the promise of the “iron rice bowl,” and had to delegate authority to local officials who themselves lacked clear solutions. The need for solutions to growing social challenges provided an opening for the rise of an independent civil society in China. The slight increases in the scores for civil liberties and political rights until 2005 reflect the extent to which ordinary citizens took matters into their own hands, working within their communities and networks to address local issues. This approach served the CCP’s needs: People saw solutions being delivered, which reduced discontent. The party could showcase its fulfillment of promises to provide support from cradle to grave. And the whole process served as a release valve for societal pressures, such as increasing inequality.

However, this level of agency by citizens became untenable to the CCP, because it posed a threat to the party’s legitimacy and thus its level of control in the broader society. The fate of local elections in China exemplifies how this situation was handled by the center. The CCP had tolerated limited elections at the village level as part of the era of experimentation, but ultimately became concerned that this channel for popular opinion posed a threat to party power. Couching its concerns in nationalism and relying on long-standing suspicion of outside influence, the CCP branded elections as a foreign concept imposed on China with the purpose of destabilizing the country. As it sought to address internal threats to its authority, the CCP closely watched external developments as well, reacting strongly to the “color revolutions” that were altering the political landscape in Eastern Europe. By the mid-2000s, the party determined that the color revolutions stemmed from domestic CSOs manipulated by foreign actors, and determined to block this threat in China. The CCP instructed local authorities to regain control of the activities of CSOs, sharply reducing the civic and political space. Once Xi assumed power in 2013, the antagonism of the CCP to civil society in general, and its anxiety about the influence of “Western liberal ideas,” was articulated to party officials in an instruction known as “Document No. 9”. The CCP began to redefine the idea of civil society: no longer was it to be independent and separate from government, but instead it became a sector that was required to meet specific government criteria. The introduction of laws around nongovernmental organizations in 2017 further tightened the space, specifically banning political and religious organizations that did not meet government approval, and creating limitations that left little space for independent civil society to function.

While the practice of rule of law in China has generally improved over the period of review, legal freedom has always been harnessed to serve the political goals of the CCP. The Chinese government has been particularly successful in using the legal system to support its political objectives, and will revert to “rule by law” when necessary. There were glimpses of judicial independence and effectiveness in the 1990s, largely as part of broader experiments occurring during that time. In particular, the CCP was aware that trust in the legal system played a crucial role in economic development. China’s early legal experiments aimed to address important questions: How could China achieve economic growth? And how could it attract companies and reassure people that China was a favorable place for doing business and supporting economic development? Yet even within the awareness of the need to foster legal trust, the party’s interpretation of the law always took precedence.

The tightening of control by the CCP over various aspects of civic and political life from the mid-2000s also affected overall legal freedoms. The modest improvement in the corruption score reflects ongoing efforts by the party to address this issue. Corruption was a significant concern at all levels in China, touching almost all aspects of peoples’ daily lives and well-being. The party recognized this as “low-hanging fruit” and made tackling corruption a priority. With ample space to work at the local level, they aimed to bring this under control, resulting in positive outcomes. However, even this social good serves the CCP’s political ends, as seen in the most recent anti-corruption campaign targeting entrepreneurs such as Jack Ma, whose wealth and independence posed a threat to the party’s authority. Regarding security, it is notable that, while China devotes significant resources to its domestic security, the overall score on this indicator has remained unchanged. Despite the extensive use of surveillance technology to control the potential for political violence and terrorism, Chinese society remains restive. Official metrics present the appearance of security and stability, but ignore the underlying discontent, evidenced by the thousands of protests that occur regularly in China. This unrest does not imply complete insecurity, but it underscores the complexity of maintaining social order in the country.

From freedom to prosperity

The data show that overall prosperity in China gradually increased until about 2014, after which it has remained basically static. Unsurprisingly, the most dramatic and sustained improvement has come in economic prosperity, with the data on income reflecting the country’s rapid economic growth. This should be recognized as a remarkable achievement by the CCP and the Chinese people. However, the reality is more complex, since this impressive aggregate achievement obscures the stark inequalities within the country that the data manifest in different ways. China’s economic growth has been uneven as urban areas were given priority and preferential treatment over rural areas. This has caused great and growing inequality; while gross domestic product (GDP) per capita may average out to an appearance of growth due to the immense scale of the Chinese economy, beyond the major cities and coastal areas China is a nation where many people still face significant poverty. And it is not only on economic metrics that China’s population experiences inequalities. The data from other charts underscore how disparities persist across different segments of the population. For an individual who falls outside the party’s accepted norms—such as belonging to a religious or ethnic minority group—quality of life is significantly worse than for the average person. While lack of progress on various forms of freedoms might be explainable by the party’s instincts to restrict liberties to maintain social controls, the inability of the CCP to deliver more equitable prosperity to all its citizens seems a squandered opportunity.

For minority rights, while the Indexes only use religious discrimination as a proxy, broader classifications of “minority” would likely reflect similar trends. Looking at the trends on religious freedom, the modest improvements seen until about 2008 diminish considerably to the present day. Since the founding of the PRC, the CCP has made concerted efforts to assimilate religious communities, which has had a significant impact on the rights and well-being of religious minority groups. While the Chinese Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, in practice the party implements a “Sinicization” of religion, requiring that religious groups adhere to the prescribed rules and guidelines set by the state. This approach means that the state exerts considerable control over religious practices, limiting the freedoms and rights of religious minorities. The CCP utilizes a range of interventions, primarily using state-controlled religious organizations to redefine how religious practices are conducted, including censorship of religious texts, and managing how religious leaders are chosen. Deviations from the prescribed framework are met with reprisals such as closure of places of worship, harassment, and detention. The systematic detention of one million Uyghurs in “reeducation centers” in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region represents the most extreme example of the CCP’s efforts to control the cultural and religious identities of minority groups.

The provision of healthcare in China is one of the few measures in which the PRC has outperformed its regional peers. The party included healthcare as part of the services that the state provided under the concept of the “iron rice bowl.” Starting from a low baseline, the PRC experimented with a variety of approaches to improve the quality of and access to health across the country, including the use of “barefoot doctors” at the rural level. Improving healthcare and access to medical services was a relatively straightforward way for the party to demonstrate its dedication to the well-being of its citizens; reforms introduced in the early 2000s expanded healthcare coverage to almost all Chinese people. However, the PRC’s healthcare system must still serve the party’s interests: the suppression of information and miscommunication about the early phase of the coronavirus outbreak in 2019 revealed ongoing systemic flaws in the country’s health services. Persons with disabilities and those living with mental health disorders remain underserved in most of the country.

China’s environment score reflects another issue on which the country has seen only limited improvement, despite the leadership’s grand commitments in policy and its investment in green technologies. China signed the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate, and the government expressed its intent to address environmental issues, including through pledges to cut emissions. However, the negative effects on citizens of pollution and environmental degradation result in ongoing protests and petitions against the government at all levels. There has been a significant crackdown on environmental activists and against any efforts to highlight environmental problems. CCP officials also seek to “manage” environmental indicators to suit the party’s needs. One striking example of this occurred during the 2008 Beijing Olympics, when officials in Beijing were concerned that air quality measurements would not meet international standards. A decision was made to suspend the activity of coal plants around Beijing, reduce the number of cars on the roads and shutter factories around the capital. These measures not only showed the seriousness of the pollution but also an utter disregard for the human cost associated with these efforts.

In terms of education, China started from a relatively low base and has made significant investments and progress. Since the founding of the PRC, the government has focused on promoting literacy and access to education, somewhat mirroring its emphasis on health. This focus was a critical factor in the country’s economic success, producing an educated workforce that could drive economic modernization. However, as in other aspects of China’s development, there are significant inequalities in the education system. Disparities follow existing lines of inequality in the country, for example between rural and urban areas, and this affects recruitment of teachers, access to education, and therefore future opportunities. The highly structured and competitive process for educational achievement creates tremendous pressure for students and their families, and leaves little room for independent, creative development. This may pose a challenge for the country as it seeks to move its economy beyond manufacturing to more advanced industries.

The future ahead

As has been noted, the conclusions drawn from the data, overall, are underwhelming: despite phenomenal growth in GDP, Chinese people have seen only modest gains (if any) across a range of freedom and prosperity indices. Meanwhile, other East Asian and Pacific countries have improved their freedoms considerably, even with slower income growth; overall, they seem to do more with fewer resources to enhance their societies and systems. When viewed through this lens, it is hard not to lament a significant missed opportunity by the CCP to create a more modern and dynamic society, one that reflects the “Chinese dream” Xi Jinping asserts is within grasp.

Of course, the CCP can argue that prioritizing economic growth over other factors was and remains the right choice for China, and that China’s citizens must continue to follow the party’s lead to ensure continued success in the future. If we accept that position, the question we need to address is whether the choices being made are sustainable. The data clearly point to a broader implication of China’s economic and social development: it has become more socially, economically, and politically complex. As the scores above demonstrate, the party has failed to share the benefits of the country’s upward economic trajectory equally among its citizens. The task of doing so will only become more challenging as the wants and needs of its citizens continue to diversify.

I have major reservations about the viability of the current model, and several factors contribute to my skepticism. The economic turmoil during the COVID-19 pandemic has raised doubts about the effectiveness of the model, even though we lack sufficient data to draw definitive conclusions. But the most striking aspect of the data is the CCP’s commitment to an inherently unequal form of governance, particularly when it comes to individual and subgroup rights. The CCP frequently touts its collectivist approach, where the well-being of the collective outweighs individual freedoms. However, the data suggest a more selective approach: in this model, certain groups are favored at the expense of others.

This type of inequality is not a new phenomenon within the CCP system. Historically, there have always been winners and losers, with the party elite and affiliated businesses reaping the rewards of extraordinary economic growth while the general population experienced more modest improvements. Yet, in the past, the wealth gap in China was often characterized as urban versus rural. What the data reveal is a shift towards absolute, rather than relative, inequality. There are clear losers in this system, including individuals and groups who have experienced a significant loss of freedoms. These groups include ethnic and religious minorities, the LGBTQ+ community, and those who advocate for more liberal—seen by the CCP as dangerous and foreign—ideals.

This discrimination is not solely identity based; it is also about values and alignment with the CCP’s objectives. As we look forward, the situation appears to be deteriorating. As the CCP sees growing threats to its authority and control, pressure will increase on individuals and groups to conform to a more limited definition of acceptability or face forced assimilation. This trend is exemplified by the genocidal “reeducation” of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, and in calls by party leaders in October 2023 for Chinese women to focus on family and traditional values. This shift towards a more rigid societal framework could lead to individuals being excluded from the benefits of society or, in the worst case, losing their social freedoms. The rapid expansion of surveillance technology and its use in determining the status of a “good citizen” provide the state with powerful tools to enforce its will. While these tactics have succeeded in managing dissent, they are likely only temporary fixes. Without substantial, systemic reform, the diverse wants and needs of Chinese people will continue to drive demands for change.

Johanna Kao is the senior director for Asia-Pacific at the International Republican Institute and is concurrently a senior nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. Her work is informed by more than twenty-five years’ experience in international political development, living in some of Asia’s most challenging and dynamic countries. Johanna is a graduate of the University of Chicago and received her LLM from the University of Hong Kong.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: People leave a Nanchengxiang restaurant that serves a breakfast buffet for the price of 3 yuan in Beijing, China, August 10, 2023. REUTERS/Thomas Peter