EU’s future prosperity will be marked by war in Ukraine

Table of contents

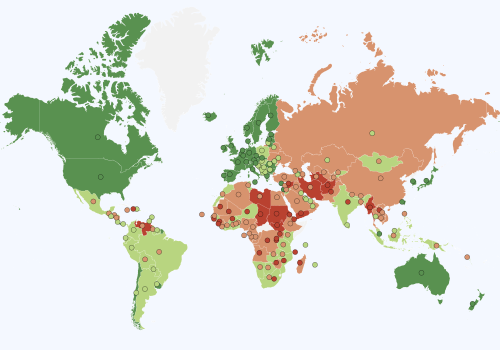

Evolution of freedom

International comparisons recognize that Europeans enjoy the highest quality of life in the world. European society benefits from great equality in income, excellent healthcare and basic education, good infrastructure, and eminent rule of law.1Anders Aslund and Simeon Djankov, Europe’s Growth Challenge (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017) However, the past decade has presented an array of challenges to European Union (EU) nations. Europe’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016 had only just returned to its 2008 level—before the eurozone crisis—and it has been losing market share in the global economy. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014; the 2015–16 migrant crisis; the UK’s secession from the EU; COVID-19; and Russia’s full-scale attack on Ukraine, the EU’s ensuing sanctions, and complete reorientation of its foreign policy toward helping Ukraine—by any historical standards, the past decade has been trying.

The EU is also the freest region of the world in the Atlantic Council’s Freedom Index, 20 points above the global average throughout the period of analysis. The increase in aggregate freedom was sustained until 2014 but has stagnated in the past decade. The main reason is the changing priorities in the aftermath of the eurozone crisis, which diverted politicians’ attention towards reducing social vulnerabilities.2Simeon Djankov, Inside the Euro Crisis: An Eyewitness Account, (Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2014) The ensuing decade brought several other challenges, starting in 2015–16 with a wave of migration from northern Africa that divided public opinion and engulfed the EU in heated debates about migration policy. These debates brought about political change in a number of European countries too, shifting the focus further from expanding freedoms and on to defining a narrower European identity. Just as this changing political landscape started to stabilize, the COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe hard, resulting in more demands for government participation in the economy and putting the emphasis on security rather than freedom. In sum, the past decade in Europe has been one of crisis abatement.

Crisis abatement has brought about new politics in Central Europe in particular, a region which was for a quarter century (1989–2014) at the forefront of increasing political freedom in Europe. The governments of Hungary and Poland, and to some degree Slovakia, have followed a path of what Viktor Orbán calls “illiberal democracy,” concentrating powers in the hands of few political leaders. This concentration has come at the expense of media freedom, judicial independence, and institutional development. The European Commission and other European institutions have responded with concerned actions to limit the loss of freedoms, with some success.

Economic freedom increased by more than 10 points until 2014, leveling off since then due to the various crises that emerged. However, there are some bright spots. Women’s economic freedom has increased continuously during the whole period, up 25 points. Investment freedom increased substantially during the period 2005–15, and has seen another upswing since as governments have tried to keep their economies competitive. This reflects the response of many EU countries to the pandemic, including significant subsidies to particular sectors of the economy, enlarging the role of the state, and crowding out the private sector. This effect continues to evolve, particularly in the energy sector where the war in Ukraine has given a jolt to Europe’s desire to be independent from Russian oil and gas.

The level of political freedom is very high in the EU, although “legislative constraints on the executive” receives a clearly lower score than the other three components of the political freedom subindex. All components of political freedom decrease slightly after 2016, coinciding with the reverberations from the migration crisis and the rise of populism in a number of European countries. The most prominent of these have been in Central Europe, where Hungary’s Viktor Orbán has been particularly outspoken on the need to curb political freedoms. The trend, however, runs deeper, with nationalist parties gaining popularity in Austria, Finland, Italy, Germany, and Sweden, among others. Europe is a more closed society now than it was thirty years ago.

From freedom to prosperity

Prosperity in the EU is around 17.6 points higher than the global average, and this gap has been stable since 1995. The trend is positive until 2019, but has stagnated since the pandemic struck. This is broadly consistent with the global pattern, suggesting that Europe is finding ways to maintain its edge in prosperity over its competitors.

The superior outlook on prosperity, coupled with geographic proximity, has made Europe a magnet for migrants from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. The pandemic reduced this inflow, as have various country-level policies to prevent migrants from entering Europe. Still, 2022 saw a significant new wave of migration from Ukraine, reaching a total of 6 million refugees towards the end of the year. And a new wave of non-European migrants has posed challenges for Italy and Greece in 2023.

The effects of the eurozone crisis of 2008–10 and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–22 are evident in the income component data. Fortunately, financial assistance to vulnerable groups was quickly dispensed during both episodes, reducing social tensions. Europe’s social safety net expanded, increasing budget deficits but allowing the crises to pass with minimal losses in welfare. Reflective of these policies, inequality is relatively low compared to the global average.

Finally, the data show sustained improvements in health and education for the EU, probably driven by countries in Eastern Europe. These countries saw social supports deteriorating at the beginning of the post-communist transition period in the 1990s. Heavy government spending, assisted by EU funding since their accession in the 2000s, has reversed these losses and led to convergence in health and education indicators across the EU.3Anders Aslund and Simeon Djankov, The Great Rebirth: The Victory of Capitalism over Communism (Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2014).

The future ahead

The next decade of EU freedom and prosperity dynamics will be marked by the war in Ukraine. The EU has committed enormous financial resources, nearly €100 billion across 2022 and 2023, in supporting Ukraine’s fight against the aggressor. It has also imposed a dozen rounds of sectoral and economy-wide sanctions on Russia. These sanctions also have negative implications for some industries in Europe, which have traditionally relied on resources from Russia. The war, in other words, has a slowing effect on Europe’s economy.

Another major impact of Russia’s war in Ukraine is that it has forced the EU to rethink the Green Deal, which the European Commission has championed for the past decade. Given Russia’s threats to Europe’s energy security, a decision was taken in 2022 to sever the dependence on Russian energy products. With only two countries—Bulgaria and Hungary—receiving postponement of these measures to 2024, Europe has quickly weaned itself from Russian oil and gas. However, this change has come at a cost: a number of countries have increased their use of coal and other high-polluting sources of energy.

The war has also sped up the process of EU integration for Moldova and Ukraine, and this will occupy the attention of Brussels institutions in the years to come. Such integration provides for a larger European market: a welcome development. The past decade has shown that Europe cannot multitask—perhaps the inevitable result of gradual consensus building among twenty-seven member states—preferring to focus on one issue at a time. The clear task at hand is helping Ukraine win the war.

The two case studies in this volume on Ukraine (by Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko from the University of California at Berkeley) and Russia (by Professor Konstantin Sonin from the University of Chicago) demonstrate what is at stake for these countries in terms of freedom and prosperity. In this chapter I suggest that, for Europe as a whole, what is at stake in the conflict is the further development of freedoms and the ensuing prosperity of Europe. Only with a free and victorious Ukraine can the EU refocus on its prosperity agenda.

In the face of Ukraine’s resolute response to Russia’s invasion, President Putin has escalated the economic warfare against its citizens by incessantly attacking the country’s energy infrastructure and cutting off vital trade channels. These acts have severely hampered the prospects for economic recovery in 2024.

A large part of Ukraine’s civilian population, an estimated 6 million refugees, is awaiting a ceasefire that would allow them to return to their homeland, as the frequent bombings and power outages have forced them to take temporary shelter in other European countries.4Oleksey Blinov and Simeon Djankov, “The all-out aggression requires an all-out response” in Supporting Ukraine: More critical than ever, eds. Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Vladyslav Rashkovan (London and Paris: CEPR Press, 2023), https://cepr.org/publications/ books-and-reports/supporting-ukraine-more-critical-ever. These immigrants look forward to reuniting with their families and continuing with their jobs or finding new economic opportunities. In both cases—whether Ukraine’s refugees stay abroad or return home—massive European help is needed to jump-start the economy. The needs are enormous: rebuild infrastructure, provide financing for entrepreneurial activities as many old enterprises are razed to the ground, open new export opportunities, and invest in the training of workers and in new technologies.

Europe’s prosperity agenda

This prosperity agenda is fourfold. First, there are wide disparities across regions within Europe. These are seen within countries, for example southern versus northern Italy, and across countries, for example Scandinavia versus Eastern Europe. A significant portion of the EU budget is directed to reducing these disparities, through investments in infrastructure, agriculture, and regional economic development. Such financial aid needs to be coupled with policies that increase economic freedom at the regional level. For example, decentralization of some tax policies combined with explicit subsidy schemes will keep more resources in underdeveloped regions and thus attract businesses and individuals who would otherwise look for opportunities in more advanced parts of the EU.

Second, increased prosperity in the EU comes from completing the internal markets for energy and financial services. These topics were discussed even prior to the 2014 annexation of Crimea, which started a series of crisis years for the EU. 2024 is a good year to go back to the original design and create a single energy market in Europe, as well as a single financial market, with a single set of regulators. Much has been written and discussed about how to achieve these goals; now is the time to act.

Third, migration has been at the forefront of European politics in the past decade. It promises to remain an issue in the decade to come. On the one hand, Europe’s demographics are such that the labor market benefits from human capital coming into European countries and putting their labor and talents into productive use. On the other hand, social tensions have risen in the countries that have received large numbers of migrants. Even in countries with few actual migrants, the specter of competition for social services and jobs has boosted the fortunes of nationalist parties that have promised to erect barriers to further migration. This issue, more than any other in Europe, inflames public opinion.

Finally, prosperity in Europe emanates from open markets. While the European market itself is large, many innovations and technologies come from either the American or Asian markets. The two other superpowers—the United States and China—have been on a collision course in asserting their economic dominance, leaving Europe to choose how to align in the global picture. So far this path has meandered, with some calling for greater protections for Europe’s own market. Such an isolationist approach is counterproductive. Europe has to remain as open as possible, assimilating leading innovations and creating the space to implement these new ideas into better production processes and products.

The Atlantic Council’s Indexes also raise some philosophical questions regarding European identity: Has the golden age of European prosperity passed, weighed down by the heavy fiscal burden of an unwieldy social safety net? Has the energy of European integration through the accession of new member states tapered off? Is federalism, in the shape of the EU, losing momentum? The past decade has not given many indications of a clear reform agenda, as Europe has stumbled from one crisis to another. The existential crisis of a war in Europe has strained the abilities of European institutions to act, yet it has demonstrated a unity that has been largely absent in previous decisions Europe has faced. This unity leads to strength and such strength is needed to overcome the many challenges that lie in Europe’s path.

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at the London School of Economics. He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, he was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: A voter enters a polling booth to cast his ballot for the EU elections at the Lufthansa flight simulator centre in Frankfurt, Germany, May 15, 2019. REUTERS/Ralph Orlowski