Georgia protests highlight urgent need for government reforms

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

Since 1995, Georgia has gone through a series of waves of reform, which are clearly reflected in the upward trend of the Freedom Index, at least until 2018. Nonetheless, I would point to two important caveats that might curb this optimistic view. First, there are significant differences between the three subindexes, as well as among their components, with the legal subindex clearly showing a lower score than the economic and political subindexes. This is probably a subtle image of the second caveat: the clear divergence between the country’s institutional framework as it appears on paper and in practice. Georgian written laws and regulations are comparable to those of the most developed countries of Europe or North America. There are always areas where improvement is possible. Still, on paper, we (Georgia) seem to be a democratic state with all necessary institutions, the balance of power, and fundamental principles of human rights protection. However, implementing our legal norms and regulations is far from complete. Therefore, some components of the Freedom Index may not present a realistic view of the actual situation experienced by most citizens in the country. Analyzing the three subindexes in detail corroborates this general concern.

Improvements in trade and economic freedoms mainly drive the positive evolution of the economic subindex, and this does capture a real advancement. We have signed free trade agreements with all major regional players, like the European Union, China, Russia, and Turkey. Our trade relations and policies are fairly free and flexible. Georgia has undoubtedly benefited from this economic openness, boosting the economy and income per capita. The acceleration of economic freedoms over the past decade is also due to the increased respect for property rights, as previously, the country had experienced severe problems in this regard, with waves of mass property dispossession.

However, developments around Anaklia deep sea port in 2019 have shaken Western investors’ confidence in Georgia. In August 2019, the US construction and development company and founder of the Anaklia Development Consortium (ADC), the Conti Group, announced it was leaving the consortium. ADC has accused the government of sabotaging the project, which received major support from Georgia’s strategic partner, the United States, and the European Union. Overall, the ADC’s departure marked a significant setback for Georgia’s infrastructure ambitions. The port was intended to boost Georgia’s economic and strategic standing as a major transit hub.

The component measuring women’s economic freedom also seems to have improved significantly, at least since 2005, but this is an excellent example of the gap between the de jure and de facto situations. On paper, Georgian legislation ensures a high level of gender equality on any economic issues, such as employment rights, ownership of assets, the establishment of legal entities, etc. However, the proportion of women is deficient when looking at top business positions or the state apparatus. Also, the gender salary gap is substantial and does not seem to be closing. Again, there is no legal standing for this reality; this is not because of a failure of the law to uphold women’s economic opportunities; it is a symptom of the patriarchal nature of Georgian society.

The score for property rights is notably lower compared to the other components because it captures actual property protection, especially against arbitrary public expropriation, a severe problem in Georgia prior to 2012. The data series shows well the gradual deterioration of the situation until 2012, when the government or its proxies were constantly—and arbitrarily—seizing private property. One of the ways this occurred was that individuals were imprisoned for a crime, and they would then buy their way out of prison by handing over their property to the state. This culture became widespread and led to extremely high numbers of incarcerations. According to the International Centre for Prison Studies, by 2012, Georgia had the highest prison population in Europe and the fourth highest in the world. In 2011, it also recorded one of the highest death rates in prisons. In 2012, the new government led by the Georgian Dream Coalition sharply amended the situation, and the component may not fully reflect the substantial improvement in property rights protection since then.

Both the political and legal subindexes illustrate well the two major episodes of institutional liberalization in Georgia, following the 2003 Rose Revolution and the 2012 change of government.

Since 2018, the country has been experiencing a dramatic institutional regression that is only slightly observable in the political subindex and not yet visible in the legal subindex components. The improvement shown in the legal subindex is perhaps the most misleading signal in the data presented here. No institution in the country needs reform more than the judiciary, and the general population and international community clearly perceive this. The deficiencies of the judicial system are the product of a selection process that is non-transparent and entirely arbitrary, which has allowed this crucial pillar of the state to be administered by a significantly small elite of judges for almost two decades. The High Council of Justice, the agency in charge of appointing judges, has been controlled by the same people since 2007, recurrently reappointing themselves to different high administrative positions. It is hard to agree with the sustained improvement shown in the judicial independence component when the interests of the ruling party and the judicial system are so closely intertwined, and the line between them is completely blurred.

A clear example of this behavior is the episode that occurred on July 22, 2024, when the judiciary unlawfully interfered with the constitutional authority of the president by suspending the appointment of a Supreme Council of Justice member. According to the Constitution of Georgia, the president has full and exclusive authority to appoint a member of the Supreme Council of Justice without anybody’s consent or consultation. However, the judiciary clearly views even a single dissenting voice as an intolerable threat to its clannish rule. Its interference with the constitutional powers of the president is not only illegal; it undermines the constitutional principle of separation of power.

Finally, the political subindex only mildly shows the degradation of the situation in the last few years, but the negative turn starting in 2018 is evident in all four components. Regarding civil and political rights, the data do not yet reflect the passing of recent laws on foreign agents and LGBT rights, which will certainly further reduce Georgia’s score in terms of civil liberties. Similarly, several amendments were passed to electoral legislation, reducing the opposition’s and civil society’s capacity to monitor and contest the government. Last, the fact that no reactionary reforms have been passed in relation to the power and capacity of parliament masks the fact that legislative constraints on the executive become fictional when the same political party runs virtually all institutions of the state. Today, barely any officials – just the president and one small-city mayor in a mountainous region of Georgia – are not part of the ruling party. Thus, there is no effective control of the executive nor any real checks and balances within the state apparatus. As this report was under development, parliamentary elections in Georgia produced an even more hostile and polarized environment, with all major opposition parties, civil society monitoring organizations, and international observers claiming major fraud. The judicial branch is by no means a safeguard of individual rights, so Georgia is rapidly and effectively falling into one-party rule, which is concerning and not fully captured in the Index.

Evolution of prosperity

The evident catch-up process concerning the rest of Europe observed in the Prosperity Index is mainly driven by the strong performance of the income and education components. Georgia has had a period of fast growth, but this would be somewhat expected given its low level at the beginning of the period of analysis. Coming from a socialist economic environment, the liberalizing economic reforms mentioned above surely produced a boost in economic growth. Even accounting for inflation and purchasing power parity, the Georgian economy has clearly closed the gap with the most developed European countries.

The Index also captures the impressive increase in years of schooling, placing the country among the top performers worldwide in the education component. However, it is essential to note that the situation is very different in terms of quality. We are not anywhere close to the best educational systems in the world, as evidenced by standardized tests such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), where Georgia falls significantly below the OECD average.

At least two components of the Prosperity Index—inequality and minority rights—may not accurately reflect the reality experienced by Georgians. Growth in income per capita can indeed advance the situation of the middle class, and this has probably been the case in Georgia, explaining the improvement in the inequality component measured by the Gini coefficient. However, the differences between regions within the country, as well as between urban and rural areas, are very sizeable. Parts of the country still rely on a barter economy, and this is most likely not captured adequately. Regarding the treatment of minorities, the positive trend of this component does not reflect the situation of several minority groups, such as the LGBTQ+ community, which has been discriminated against and disadvantaged intentionally and will likely suffer even larger stigmatization given the new legislation passed by the parliament framed as “Protection of Family Values.” Sadly, the government ignores the abuse and discrimination not only when it comes to employment, for example, but also the highly violent cases of physical assault and harassment. In recent years, Georgia witnessed several instances of violent attacks against LGBTQ+ civil society organizations, as well as individuals and politicians who champion minority rights. Most of those attacks were large in scale and well organized. One of the most outrageous instances of brutality that shocked Georgia was the murder of 37-year-old transgender model Kesaria Abramidze on September 18. Coincidentally, this hate crime happened the day after anti-LGBTQ legislation was passed. Brutality was widely displayed on the streets of the capital city, Tbilisi, during the attacks of July 5, 2021, when Tbilisi Pride was violently disrupted by far-right groups, leaving 53 media workers who were covering the events injured and one dead. Anti-LGBTQ+ protesters also raided offices belonging to the NGO Tbilisi Pride and Shame Movement, which organized the event. This was not an exceptional event. Virtually every time the queer community comes out in public, they are pushed back into the social periphery by crowds led by far-right activists. It is also true that virtually every time, the police and state fail to protect LGBTQ+ people, control the mob, arrest their leaders, or bring them to justice. There is a dominant perception that the authorities are collaborating with violent groups.

The only possible explanation for any increase in the minority component since 1995 may be found in the efforts made in the educational system to integrate ethnic minorities through a common language and other inclusive educational policies. Those efforts notwithstanding, a disturbing downturn in minority rights was visible from 2021–22. Despite some improvement since then, the decline will likely become apparent again in the coming years because of the way the ruling party and its proxies control all public spaces and opportunities and fight differences. This will inevitably reduce fair access to public jobs and business opportunities for those not politically aligned with them.

It is certainly true that substantial effort has been put into improving the healthcare system in the last couple of decades, and this is observed in the rise in the health indicator score. Most of it has been directed to primary care, children’s health, childbirth, pregnancy, and so on, and not so much to advanced medical care such as surgery or the treatment of serious conditions. This is why those Georgians who can afford to do so go abroad to get quality care for serious illnesses. According to the data from the Georgian statistics department, the number of citizens of Georgia going to foreign countries for medical care doubled in 2023. This explains why the healthcare gap with the rest of Europe persists.

COVID-19 provides a good example of this gap. At first, it is surprising that the data seem to show that the COVID-19 pandemic hit Georgia harder than the rest of Europe, as the country’s robust primary healthcare system should have allowed it to cope with the crisis relatively well. However, the problem was mismanagement and the absence of a structured, systematic approach. Georgia was doing well as long as the government maintained a state of emergency—run jointly by police and the military. Rules were as rigid as in any democracy across the globe. However, as the economy was suffering and people slowly started disobeying the rules, the government understood the need for change and eased the restrictions. This is where major shortcomings of governance presented themselves, and the number of infections started to grow dramatically. The COVID-19 crisis showed all the deficiencies of the governance system in Georgia. The state can manage the most difficult situations, provided it can do so with a draconian response based on police rule, but when you need a nuanced, rules-based approach with basic freedoms for citizens guaranteed, the government fails every time. Democracies are truly tested during a crisis, and the best test is to see whether policies remain balanced while dealing with the emergency. This is where Georgia fails every time.

The path forward

Georgia stands at a critical crossroads. One of the most significant risks Georgia faces is the ongoing influence of Russia, which exerts considerable power through economic, political, and military channels. Russian-backed hybrid threats present ongoing dangers that could undermine the Georgian government and disrupt reform efforts. Political polarization and governance challenges constitute another major hurdle. The political climate in Georgia is often plagued by fierce rivalries and divisions, hindering the passage of essential reforms and destabilizing governance. Without a shared vision among political parties, advancements in critical areas such as judicial reform, anti-corruption initiatives, and economic policy risk stagnation. The absence of political consensus diminishes the government’s strength and undermines public confidence in democratic institutions. To achieve greater freedom, a concerted effort is needed to build multiparty agreement on vital reforms and nurture a political culture prioritizing national interests over individual party agendas.

Economic inequality and emigration threaten Georgia’s progress. Despite economic growth, high unemployment, regional disparities, and limited opportunities push many young Georgians to seek work abroad. To sustain a robust economy and reduce emigration, addressing these inequalities, investing in regional development, and creating jobs for youth are essential.

Georgia must urgently reform its judiciary. An independent judiciary is vital for attracting foreign investment and building public trust. However, the judiciary faces corruption and political interference, obstructing economic and democratic growth. Legal reforms that ensure fair and transparent processes could restore public confidence and improve the business environment, making Georgia a more appealing investment destination.

As the majority of the population is predominantly asking for practical steps to bring Georgia closer to the EU and eventual membership, nondemocratic moves and decisions of the government stand as an impediment to this popular demand. This path forward will hinge on Georgia’s ability to integrate more closely with Western institutions, manage regional security risks, and drive economic modernization. Several key drivers of change will shape the country’s progress toward freedom and prosperity. Still, significant challenges—such as Russian influence, the authoritarian nature of the government, political polarization, and social inequality—could impede progress. By addressing these obstacles and embracing transformative reforms, Georgia can lay the groundwork for a resilient, prosperous, and democratic future.

Georgia’s drive for European integration is a significant factor in its future growth. The populace’s strong pro-European stance serves as a primary catalyst for change. Important milestones, like visa-free travel within the EU for Georgians and free trade agreements, represent advancement and inspire citizens’ hopes for EU membership. These successes also provide clear leverage for the government to sustain current benefits and advance even more.

Economic modernization is a crucial factor. Georgia’s economy has traditionally relied on agriculture and low-value exports, heavily dependent on the Russian market, which risks vulnerability to disruptions. Future development needs to shift toward services, tourism, technology, and trade for sustained growth. Investing in infrastructure—roads, ports, telecommunications—and achieving energy independence through renewables can enhance economic resilience and reduce reliance on external energy. Digital reforms and a focus on tech startups provide new opportunities, particularly for youth, while increased foreign investment may boost economic vitality. However, these changes require political stability, a favorable business environment, and better governance.

Regional security and stability are crucial for Georgia’s future. The South Caucasus is geopolitically sensitive, and prone to conflicts. For sustainable development, Georgia must ensure a peaceful environment domestically and with neighbours like Turkey and Azerbaijan. Partnerships with the EU and NATO are essential for countering security threats and fostering a stable regional investment climate.

Georgia’s vibrant civil society drives democratic progress. Citizens push for transparency and reforms through NGOs and grassroots movements. Increased civic engagement pressures the government to implement meaningful changes. Support for independent media ensures an informed citizenry to hold officials accountable. Civic education for youth encourages engagement, creating a more participatory political landscape.

Georgia’s future freedom and prosperity depend on leveraging European integration, driving economic modernization, unifying the country, and strengthening civil society. By fostering resilience, diversifying its economy, and ensuring political stability, Georgia can achieve growth, and greater freedom. Although the journey is complex, sustained commitment could position Georgia as a model of democratic resilience and economic innovation in the region.

Tinatin Khidasheli is head of Civic IDEA, a Georgian think tank countering Soviet legacy and Russian propaganda while advancing Georgia’s defense policies. Author of the first Georgian language book on hybrid warfare, Khidasheli teaches at Caucasus University, Georgian Institute of Public Administration, and Ilia University. Formerly Georgia’s first female defense minister, Khidasheli also chaired the Parliamentary Committee for European Integration. She holds an LLM from Tbilisi State University, and an MA in science from Central European University.

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous Edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the data

About the center

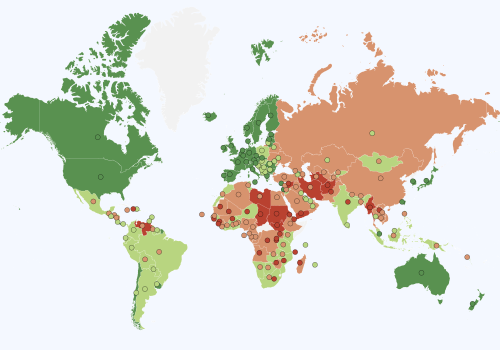

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: Demonstrators hold a rally to protest against a bill on "foreign agents", near Georgian Parliament building, in Tbilisi, Georgia, May 13, 2024. REUTERS/Irakli Gedenidze

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media