Greece’s population must be given reason to trust its government

table of contents

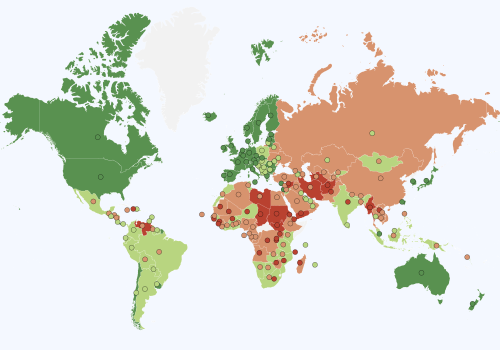

Evolution of freedom

At the onset of the crisis in the European periphery—around 2008—Greece was significantly more prosperous than its institutional quality would have suggested; property rights, legal institutions, government efficiency, control of corruption, and economic freedom were all far lower than in nations with comparable incomes per capita. The GDP-institutions difference was evident in all crisis-hit countries, such as Spain and Portugal, but it was the largest in Greece. Given the strength of the institutions-development nexus, this paradox was unlikely to last indefinitely. It would be resolved either by improving institutions and enhancing economic freedom, as a way to “firm up” the prosperity already achieved—or by income and prosperity falling away. Sadly, the latter took place, and dramatically so. It is hard to underestimate the profound and prolonged toll of the 2008–16 crisis. Greece lost a quarter of its output, unemployment tripled, hundreds of thousands of talented Greeks emigrated, the welfare state collapsed, and poverty became increasingly evident. While the fiscal profligacy of 2004–09 and deteriorating competitiveness were instrumental, the Greek economic crisis was essentially institutional.

The economic adjustment programs agreed between the Greek government and the “troika” of international lenders (International Monetary Fund, European Union (EU), and European Central Bank) focused—obsessively—on austerity and reforming the inefficient pensions system; yet, some much-needed changes in labor, product, and capital markets took place. Reforms such as opening “closed professions,” making hiring and firing easier, strengthening the Competition Commission, and making it easier to start a business contributed to the mild improvement in the aggregate Freedom Index during 2010–15. However, despite the progress, there is still a significant gap between Greece and most (developed) European countries in numerous proxies of institutional quality and economic liberty. Given the causal link between institutions, economic freedom, and development, enhancing the institutional apparatus is still needed.

One would have hoped that, as the country was leaving the crisis (and austerity) behind, the policy focus would switch from government finance to enhancing the legal protection of citizens and investors, strengthening property (and intellectual property) protection, investing in public administration, and making product markets more competitive. However, neither the Syriza/Anel coalition (2015–19) nor the New Democracy administration (2019–present) have instituted genuine institutional reform, including making markets more competitive, strengthening investor protection, speeding the judicial process, and safeguarding the independence of public agencies. Despite relatively meager post-2016 growth of about 1.0–1.5 percent during 2016–19 and around 1.8–2.4 percent more recently (2023–24), there has been little discussion on the need to liberate and modernize the Greek economy—much needed for a genuine new cycle of convergence.

Delving into the components of the economic subindex sheds light on the many challenges and the few successes. Starting with the latter, an encouraging development is the substantial rise of the component measuring women’s economic freedom. Fortunately, this topic has gathered ample consensus across the political spectrum and society following the progressive family law reforms in the early 1980s (abolition of dowry, equal pay, women’s right to keep their family names, and many others). Administrations of all political colors and leanings have pushed in the same direction, advancing equal rights and opportunities for men and women. In the past decade, we have seen genuine efforts and legislative measures to improve matters for the LGBTQ community. Despite internal opposition from its vocal right, the center-right administration proceeded aggressively on this front in 2024. Nonetheless, women’s labor force participation still lags considerably behind other (Southern) European countries, reflecting “conservative’’ attitudes and a considerable child penalty on wages. In the 2010s, the country improved its already strong score on the trade freedom component, which reflects tariffs, hidden restraints, quotas, and exchange rate barriers. This progress built on the opening of trade in 1980 when the country joined the European Community, and Greece’s adoption of the euro in 2001.

In contrast, the components of investment freedom and property rights have not shown much improvement over the past three decades, once averaged. While one can always question the fluctuations, investing in Greece, registering property, and starting a business are costly, time-consuming, and somewhat uncertain, as there are myriad processes and licenses investors need from numerous organizations. And while the current administration has rightly prioritized big, often deemed “strategic” investments—including offering assistance with licenses and providing subsidies—the situation for small and medium-sized enterprises or smaller-scale investments is still anachronistic, formalistic, and cumbersome. While not reflected in the subindex, many entrepreneurs and businesspeople complain about extensive delays and red tape in disbursement of national or EU subsidies. Perhaps it is no wonder that most of the growth of the past years, around 1.5–2 percent per annum, reflects consumption rather than much-needed—and expected after a significant downturn—investment.

Greece celebrated its democratic golden jubilee in 2024, fifty years on from the fall of the military dictatorship in 1974. Over the past half-century, the country enjoyed political freedom and an expansion of civil liberties. In line with this, the political subindex, which tracks the quality and competitiveness of the elections, civil liberties, and political rights, exceeds 95 (out of 100) for most of the years in the dataset. The slight decline during the second half of the crisis most likely reflects riots, demonstrations, and attacks by far-right groups on immigrants. The stability of Greek democracy, despite the severe and prolonged economic downturn and the associated surge of far right and radical left populism, speaks to its resilience. It is the stable democracy that should serve as the basis for the desperately needed economic recovery.

The legislative constraints on the executive component paints a less rosy picture, which is concerning given the strong link between legal quality, financial, and economic development. To start with, Greece’s score throughout the 1990s, 2000s, and early 2010s is not perfect, reflecting the tendencies of various administrations to intervene in the judiciary, the media, and independent agencies. Besides, before the crisis, members of parliament rarely challenged their party’s cabinet. The forty-point drop in the legislative constraints on the executive component of the past years perhaps overstates the case. But while one can reasonably question the apparent size of the fall, it should be a wake-up call for the political system, civic organizations, and Greece’s partners in the EU. The fall in political rights likely reflects the massive-scale spyware scandal, where for several years between 2019 and 2023, dozens of individuals—including members of parliament (MPs), opposition leaders, journalists, businesspeople, judges, and even cabinet members and the joint chief of staff—were under surveillance by the Secret Service, under the direct control of the then-prime minister’s office and a still-mysterious private company. Many targets were under surveillance by both the Secret Service and the private agency. Perhaps even more alarming, the investigation has been slow, key witnesses have not been called upon to testify, and the administration and the judiciary have shown little interest in shedding light. Most targets, including ministers, did not even question who was spying on them or why. Media outlets connected with the administration and government-aligned MPs attacked independent agencies, the courageous journalists who uncovered the scandal, and even the independent committee of the European Parliament that tried to shed some light. To make things worse, the judiciary—perhaps nudged by the administration—has been absurdly slow in investigating other cases with significant public interests, such as the conditions of a devastating train accident in 2023, where dozens of people, mainly university students, died, and the drowning of hundreds of helpless refugees in the Sea of Pylos (in Messenia) in June 2023. Another alarming development of the past decade is the evident effort of the administration to control the main media outlets. Historically, most Greek parties, in government and opposition, tried to influence newspapers and TV; however, there are nowadays clear signs that very few of the principal media outlets would oppose the government. Let us be clear, though: Greece’s decline in constraints on the executive is rather subtle and a far cry from some other European cases, such as Orbán’s Hungary.

The legal subindex reflects the low quality of bureaucracy, the problematic judiciary, and weak corruption control. As in other European countries on the peripheries of the continent, the quality of legal institutions deteriorated gradually in the 2000s. The reforms of the early 2010s tried to improve the absurdly slow judiciary and reduce red tape. Still, their impact was muted as they were mainly ad hoc, and they went hand-in-hand with an exodus of public servants, significant salary cuts for judges, legal personnel, and prosecutors, and underinvestment in IT and infrastructure. People’s trust in courts—and other core free-market liberal institutions—plummeted during the economic crisis (2007–15). The quality of legislation, already far from great, deteriorated after 2012, as Greek governments passed multiple laws with tight deadlines, insufficient preparation, and without thinking of the big picture. In addition, MPs’ lawmaking skills are evidently low and have deteriorated. The recent decline of this subindex reflects rising informality and, to a lesser extent, worsening security, both of which are hard to verify. However, progress was made after 2019, as the new administration went forward with a well-designed and professionally implemented policy to digitize the public sector, which received a massive boost during the pandemic. In addition, the digitization and reforms of tax authorities during the crisis years have helped curb tax evasion in small businesses. Coupled with the boom in tourism and hospitality, these have raised much-needed public revenues.

Finally, the sharp drop in security during the 2008–15 period mainly captures the socio-political unrest of the time, with numerous demonstrations and protests that eventually ended with minor clashes with the police. Common criminality in Greece has increased somewhat, although the country is still safe and secure.

Evolution of prosperity

Being a composite of six components, some slow-moving (like education and health), the Prosperity Index only slightly reflects the dramatic effects of the debt crisis of 2010–15. The income plot does give an accurate perception of the magnitude of the loss of output per capita the country experienced during the crisis, with the fall in the Greek score around five times larger than the European average. While much ink has been spilled on the causes of the Greek crisis with the 25 percent output loss, there has been little discussion of the mediocre recovery after 2015—the point at which the Syriza/Anel government performed a U-turn and the country stayed in the Eurozone. Economic reasoning and past experience from other crisis-hit countries suggest fast, albeit temporary, growth driven by investment following such a vast output loss, an “internal devaluation,” and the elimination of exchange rate risk. Alas, growth has been slow, about 1–1.5 percent in 2016–19, and somewhat higher, around 2 percent, after the pandemic in 2023–24. In addition, most of the recent growth comes from hospitality, tourism, construction, and real estate, while growth in manufacturing is close to nil. The current administration appears satisfied with the pace, contrasting it with the close-to-nil growth experienced by Germany and the other advanced Eurozone countries. However, given that growth in the “frontier” economies (e.g., United States, United Kingdom, Germany) has been historically about 1.7–2.0 percent per annum, Greece needs much faster growth, driven by investments in IT, infrastructure, machinery, and equipment, for at least a decade to catch up and converge again to the European core. While many citizens, businesspeople, journalists, and policymakers seem satisfied that the country has left the worst of the crisis behind, Greece is today the second poorest country in the European Union, behind Bulgaria, and the least developed euro member. Average output growth of about 2 percent, typical of the wealthiest countries, is not something to celebrate, and given the disaster of the crisis, it is, to me, a pathetic target.

The component of economic inequality points to a non-negligible fall. However, the data are far from completely reliable due to tax evasion (undeclared income), high levels of informality, and the large share of small enterprises. The crisis harmed the middle class relatively more. Professionals, public, and private sector employees suffered the most from the substantial tax hikes of the 2010–18 period. The middle class and the poor also suffered the most from the sizable expenditure cuts that hit the welfare state.

Greece’s scores are high in the education and health components, but some important caveats are in order. First, the education component only reflects years of schooling, crucially missing their quality. Sadly, international test scores and other measures of the quality of the educational system illustrate the (very) dire conditions in primary and secondary schools. The university system is in poor condition, with the crisis making things worse. Improving the quality of education is a sine qua non for a sustained recovery, raising real wages, and bringing down chronically high unemployment. Besides, an analysis of PISA scores pinpoints considerable inequality and low intergenerational mobility in education, especially when adjusted for quality. This further shows that prioritizing human capital will bring much-needed growth and opportunity for the left-behind. The enduring deficiencies of the university system, which generates degrees rather than skills, are at the core of the persistence of unemployment and low wages. Even during the high growth era of 1994–2005, the unemployment rate was double-digit. Today, despite the emigration of Greeks in the crisis years and the (mild) recovery, unemployment still hovers around 10 percent. Sadly, a significant effort to reform tertiary education in 2010 was abandoned and, in some domains, even reversed. A recent attempt to redesign the sector has been partial at best, prioritizing the establishment of foreign private universities in the country which, while needed, does not address the core of the problem in public universities.

Second, the health component only reflects life expectancy, missing morbidity, and other aspects. The pandemic revealed the deficiencies of the welfare state. The national health system, established in the mid-1980s, had already weakened in the 2000s and further deteriorated during the crisis, hit by austerity, misallocation, and negligence. During the years of the economic adjustment programs, doctors left en masse (for abroad or the private sector), there was limited investment, and no significant recruitment of nurses and support personnel. Even now, hospitals do not publish detailed accounts and the system is plagued by inefficiencies of all sorts. One can only hope that modernizing and reforming the national health system will soon be the focus of genuine policy action. Sadly, modernizing and strengthening the health system are not the administration’s priorities.

Greece’s relatively higher level of minority protection than the rest of Europe, at least until 2015, is probably due to its high ethnic, linguistic, and religious homogeneity. Women’s legal status is strong, although gender discrimination in the labor market is present and one rarely sees women running big corporates or holding senior management posts. Greece integrated a large influx of immigrants from Albania and Eastern Europe in the 1990s and early 2000s, with immigration contributing to the solid growth in these years. However, as the crisis intensified, far-right and xenophobic groups and parties started attacking immigrants. As thousands of refugees from Syria, Libya, Asia, and Africa began to reach Greek islands en route to Northern Europe, a portion of the population started exhibiting anti-immigrant sentiments. The significant fall in the minority component score since 2016, especially from 2019, will surprise most of my compatriots. I think it is somewhat unfair. It most likely reflects criticism of the Syriza/Anel and New Democracy administrations in terms of their treatment of refugees in camps and the “pushbacks” of migrant boats in the Aegean Sea. For instance, tragic episodes like the sinking of a migrant boat in June 2023 in which hundreds of refugees died outside Pylos, receive more attention from international than local media and authorities. Besides, one rarely sees immigrants or minorities in senior jobs.

Finally, the sustained improvement in the environmental component is again the product of different administrations’ consistent efforts to incentivize clean energy sources in the last decade. Fortunately, there is little divide across the political spectrum about this topic, and the EU’s impulse is unquestionable. However, the environmental measure used in the Prosperity Index does not capture Greece’s most pressing environmental challenges today, related to the conservation and protection of the islands and the pristine countryside from overbuilding. Recurrent wildfires and floods, a rarity in the country, have had a huge environmental toll. I am not optimistic on this front, as the government has limited The Path Forward capacity—and perhaps will—to impose construction, forest, and building legislation nationwide. Executive orders restricting or banning new building licenses in some Greek islands have not been enforced. On one hand, the government initiated an ambitious plan during the pandemic to make the island of Astypalaia eco-friendly; on the other hand, state agencies have granted planning consent for a tourist village that will almost double the island’s occupancy. Paradoxically, the state subsidizes hotels in the most overbuilt areas and islands. Construction permits and forest and seaside protection are mainly in the hands of municipalities and local agencies; they are decentralized, understaffed, have limited IT systems, and are prone to corruption. There are limited, if any, interventions concerning water management and wildlife protection. In addition, starved of funds and resources since the crisis, local communities, municipal leaders, and policymakers often turn a blind eye, even to conspicuous violations of environmental protection.

The path forward

As Greece celebrates fifty years since the restoration of democracy there is much to consider for the decades ahead. First, while the country enjoys free and fair elections within a competitive political landscape, freedom and civil liberties must be sustained. While the burst of populism that hit the country alongside the deep crisis has faded, trust in core democratic institutions is in decline. Restoring trust is a must. Strengthening the judiciary, enhancing checks and balances on the executive, and investing seriously in the rule of law are sine qua nons, not only to restore confidence in democracy but also to promote much-needed economic growth. The priorities should be to enhance institutions, tackle corruption, promote economic freedom (by bringing down cartels and freeing product markets), and seriously invest in public administration and independent agencies (e.g., competition authority). I am afraid that while these reforms are obvious, in practice, they are not on the administration’s priority list.

Second, Greece desperately needs a new round of convergence and investment-led growth to raise wages and create opportunity. Human capital, much of it abroad, coupled with capital from markets and the EU, can bring back much-needed growth and hope.

Third, Greece must carefully manage the trade-off between the environment and growth. Rather than destroying the landscape, pristine beaches, beautiful historic settlements, and forests, the administration, parties, and local communities must use that beauty and history for growth and resist the temptation of “easy” money from its exploitation.

Fourth, the country used to—and to some extent still does—take pride in the high life expectancy stemming from the Greek diet, strong family ties enabling risk sharing, a decent national health system, and the high education of many Greeks. Investments in education and health were at the core of upward mobility, hope, and high growth after World War II, and the restoration of political freedom in the mid-1970s. The land of Aristotle, Socrates, and Pericles needs to once again become a land of opportunity, centered around human capital, for its people.

Elias Papaioannou is a professor of economics at the London Business School, where he co-directs the Wheeler Institute for Business and Development. Papaioannou, a fellow of the British Academy, also serves as a managing co-editor of the Review of Economic Studies. He has worked at the European Central Bank and Dartmouth College and held visiting professorships at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard. His research covers international finance, political economy, economic history, and growth.

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

explore the data

about the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

stay connected

Image: A view of the Acropolis and Plaka from a rooftop bar in Athens, Greece, January 3, 2025. REUTERS/Louisa Gouliamaki

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media