Mexico’s vital institutions face decline

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

The Freedom and Prosperity Indexes have served as a useful tool for observers and policymakers alike to identify trends and historical evolution of countries. In the case of Mexico, the Indexes rank the country as “mostly free” and “mostly prosperous”. However, recent declines in several indicators are early warning signs of an erosion occurring, at least on some fronts. Complementing the findings of the Indexes with qualitative insights can provide a nuanced understanding of the drivers, trends, and challenges that Mexico is facing.

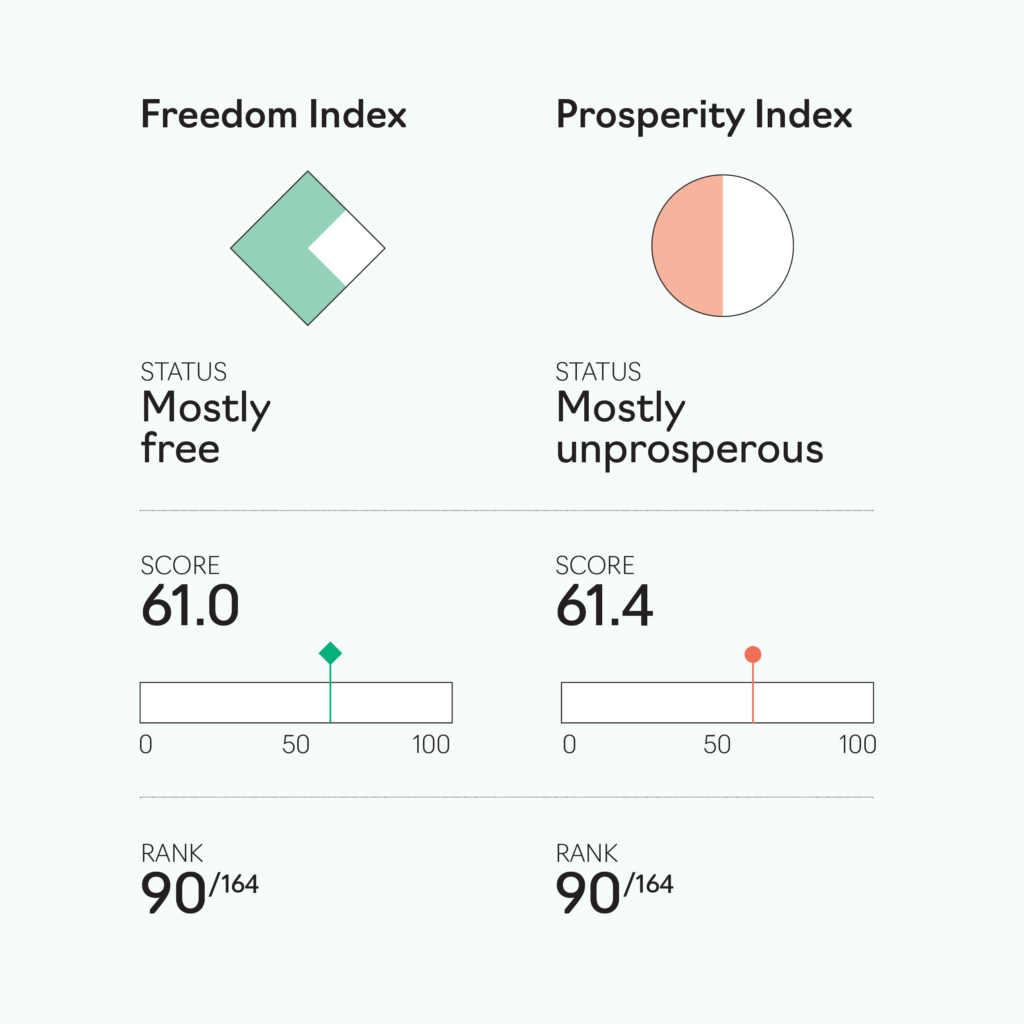

Between 2018 and 2022, Mexico’s overall freedom score dropped from 66 to 61, placing it 90th out of 164 countries. This decline in ranking is unique among Latin American nations, which maintained an average aggregate score of 65. During this period, the most significant declines came in Mexico’s legal freedom score, which fell from 53 to 47 (now ranked 117) and its political freedom score, which fell from 74 to 65 (now ranked 102). In contrast, the economic freedom score remained relatively stable at around 70 (ranked 52). While various political and economic factors likely contributed to these trends, it is worth noting that significant changes have occurred since President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO, by his acronym), assumed office in December 2018, which have had a notable downward impact on these freedoms.

When it comes to legal freedom, the subindex records significant declines with respect to judicial independence, clarity of the law, and bureaucracy and corruption that are attributable to previous governments, but which have been exacerbated since 2018. While legal institutions such as the Supreme Court of Justice and regulators remain relatively autonomous overall, a large driver of the declining trends stems from the current government’s direct and tacit attempts to undermine their functioning and independence.

For instance, the decline in judicial independence scores, from 60 to 47 between 2018 and 2022, is largely due to ongoing attempts to influence the Supreme Court and control their key decisions. Since taking office, AMLO has appointed four of the nine Supreme Court Justices. Notably, two of them have aligned with the president’s political agenda, and the other two, in the words of the president himself “turn out to be conservatives,” meaning that they are independent—as they should be—and do not abide by his mandates. Most recently, the president directly appointed a new Justice to a vacant seat on the Supreme Court—a political loyalist and former Morena party activist. The interference in key decisions is overt at times: for example, AMLO said it would be an “act of treason to the country” if the court ruled against the Electric Industry law, despite serious concerns over the law’s constitutionality. Two key rulings regarding this law were expected in September 2023, but have been delayed as the energy ministry introduced a legal complaint regarding potential conflicts of interest of two Justices of the court. The law prioritizes the state-owned utility CFE, undermining private sector participation (among other issues) but it is a key plank in the president’s nationalistic energy agenda.

The government is also attempting to undermine the Supreme Court in other ways, for instance by engaging in confrontational and polarized criticism of the court’s president, including endorsing public protests against her, underscoring and increasing the political pressure on Justices. The government also seeks to exert financial pressures over the court. On October 25, 2023, Congress approved cuts of US$815 million to the Supreme Court’s budget—granting the court 18 percent less than had been requested for the 2024 budget (and representing a 2.7 percent reduction compared to the 2018 budget, according to México Evalúa). Moreover, the party in government presented a bill (September 2023), supported by the president, to eliminate the Judicial Power’s trust funds, which was eventually suspended by the Supreme Court itself, proving that the measure would undermine the labor rights of workers, who were the final owners of the resources: the cuts aimed to eliminate fourteen trusts specifically earmarked for employees’ pensions and healthcare, as well as implement recent judicial reforms that have expanded the responsibilities of the High Court.

The decline in the clarity of the law score, from 48 in 2018 to 34 in 2022, is a result of several policy shocks which take a toll on business confidence. The current administration has created persistent uncertainty, especially regarding the enforcement of crucial regulations governing contracts, tariffs, and prices, that are necessary for maintaining a competitive market. This ranges from the cancellation of the Mexico City airport project, despite it being 70 percent complete, to hindering competition in the electricity and renewables market. As a result of this, on July 19, 2022, the United States and Canada initiated a consultation under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to discuss Mexico’s energy policies, in particular claiming a violation of competition and clean energy commitments. The consultations are ongoing, though dispute settlement mechanisms have not been triggered as the parties are expecting the Supreme Court to rule on the constitutionality of the Electric Industry law.

The administration recently delivered yet another significant blow to business confidence. On October 5, 2023, the Federal Civil Aviation Agency unilaterally altered the tariff base regulation for the concessions of nongovernment airport operators—without any previous consultation. Ultimately, this uncertainty makes it difficult to assess the regulatory risks, and results in added costs for companies and cancellation of investments in the country.

Since 2018, there have been budget and staff cuts to key ministries and autonomous institutions, jeopardizing Mexico’s bureaucratic structure and redirecting resources to the president’s favored projects. In addition to the budget reductions to the Supreme Court, the 2024 budget proposes cuts for the health, economy, and tourism ministries (21 percent, 56 percent, and 77 percent respectively, compared to the 2019 budget, the first of AMLO’s presidency). Instead, resources are being redirected to ministries overseeing the president’s social programs and fiscally unviable pet projects, resulting in significant increases in funding for the energy, well-being, and defense ministries (609 percent, 266 percent, and 176 percent respectively). These shifts in spending reflect a broader trend towards centralized decisionmaking and an enormous role for the military—a tendency that has adversely affected the “bureaucratic effectiveness” indicator of the Index. The centralization of government procurement contracts is one example, which, together with a lack of delivery capacity, led to a severe shortage of medicines in 2021, according to an independent audit by Auditoría Superior de la Federación (ASF).

And while these changes have been justified on the grounds that they would reduce corruption, Mexico has not made much progress on this front, ranking 126 of 180 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index in 2022, with a score of 31 out of 100, a decline from 35 in 2014. Particularly worrisome has been the involvement of the military in many economic activities, including managing ports and customs, executing the president’s infrastructure projects, and even owning a commercial airline. Citing national security concerns as a justification, these changes have led to opacity in the disclosure of government contracts and an increased practice of direct assignments instead of public and transparent bids—worsening rather than abating corruption concerns.

Most recently, before the year end of 2023, the president has raised the stakes: he has indicated that the autonomous institutions will be disbanded altogether, as (in his own words), “they don’t serve the people and are at the service of minorities.”

Another notable aspect contributing to the decline of legal freedom in Mexico since 2018 is the shifting security landscape, characterized by an increasing reliance on the military for day-to-day law enforcement activities, and the “hugs not bullets” policy, which essentially advocates for a nonconfrontational stance towards organized crime. The traditional presence of civil police has been superseded by the emergence of military police, or in some instances, direct military intervention in street-level security operations throughout the country, creating human rights concerns. And the lack of actions against organized crime has allowed it to become more powerful in certain parts of Mexico, resulting in a rise in violence and insecurity across the country. According to the Executive Secretariat of the National System of Public Security, homicides during the five years of AMLO’s government have reached 156,479 (as of November 2023), more than the whole six years of the previous administration.

On political freedom, the executive has sought to undermine the National Electoral Institute (INE), not only by attempting several constitutional and legal reforms, but also by significantly slashing its budget. The INE was established in the 1990s and serves as a crucial pillar of Mexican democracy, organizing elections and ensuring fair electoral processes. Although attempts to reduce the institute’s independence and power have so far faced congressional and wider public rejection, the president plans to present a new bill during his last year in government (2024), arguing—without proof—that the institute shows a “lack of independence and impartiality.”

On yet another metric, the decline in the legislative constraints on the executive score, from 54 in 2018 to 36 in 2022, also contributed to the overall decline in political freedom. AMLO’s landslide victory in 2018 gave his ruling Morena coalition a significant majority in Congress and, although it shrank in the 2021 midterm elections, the coalition still holds 55 percent of the seats in the House and 59 percent in the Senate. The pressure on ruling coalition legislators to vote as a bloc has, in most instances, allowed the president to capture Congress and enabled major reforms in education, labor, and energy. These reforms have been approved with little or no input from the ruling party, coalition partners, or opposition legislators, undermining the process of checks and balances. The Senate has remained an important counterweight, particularly with regard to constitutional reforms; and Congress too has recovered some of its balance, since the ruling party lost its absolute majority during the 2021 midterm elections.

The active undermining of the legislative processes and political pressure on opposition legislators to vote in line with the president’s priorities have also become more common. For instance, the reform of the electoral system was ruled unconstitutional (June 2023) by the Supreme Court due to violations of the legislative process. These included not giving legislators adequate time to debate and consider the bill, as significant last-minute amendments were submitted less than three hours before the vote, and further changes were unlawfully incorporated after its approval. This and similar incidents highlight the overt sidestepping of procedure that has become more common in this legislature. Overall, this undermines the proper functioning of the legislative body and weakens the separation of powers enshrined in the Constitution.

On economic freedom, the transformation of the relationship between the state and the private sector has been a defining characteristic of Mexico’s economic landscape since 2018. Central to this shift is the government’s altered perception, wherein the public sector is not solely viewed as a regulatory entity but as an active participant in economic activities, thereby fostering a growing inclination towards statization. Though property rights are granted in the Constitution as an individual freedom, this ideological shift has put such individual rights on a weaker footing.

In this evolving climate, several endeavors to assert state influence over private enterprises have been initiated, although not all have materialized into full-fledged nationalizations. Notably, instances have arisen where the government intervened in the decisionmaking of private companies, effectively nudging them to relocate their operations according to the state’s regional development agenda. An example is the relocation of a beer factory from the north to the underdeveloped south of the country. This is a concerning trend, wherein the state’s vision for regional development takes priority over the autonomy of private enterprises. This heavy-handed approach not only undermines the principles of competitiveness and private decisionmaking but also poses a direct threat to the fundamental tenets of property rights. Such coercive tactics, veiled under the guise of state-driven development, demonstrate a fundamental disregard for the traditional mechanisms of incentivization and market forces, creating an environment of uncertainty for private property holders.

Companies in the transportation sector, in particular railway concession holders, have recently been the target of government aims to influence private decision making. In May 2023 an attempt was made to expropriate rail infrastructure owned by Grupo Mexico’s Ferromex, to be repurposed for the Trans-Isthmic Corridor project; and in October 2023, the president issued a decree to pressurize concession-holders to invest in passenger trains and being obliged to change their business models to offer passenger services. These events are a window into the government’s approach to the private sector, offering some explanation for the deteriorating business climate and challenges to property rights reflected in the Index.

Preceding the recent developments, the challenges to property rights have long been exacerbated by the pervasive influence of organized crime, particularly through extortion and illegal impositions. This unfortunate reality has only been intensified by the implementation of the “hugs, not bullets” policy, inadvertently providing illicit entities with greater leeway to perpetrate their exploitative activities.

The erosion in freedoms is neither linear nor universal, but the examples above clearly point to some worrisome trends that have contributed to an overall decline in freedoms in Mexico, and which present clear warning signs for the way forward.

From freedom to prosperity

Mexico’s prosperity score has been stagnant since the start of the Index, oscillating between 61 and 63 since 1996 (ranking 90 out of 164 countries in 2022). Its aggregate score is now 4.1 points below the Latin America & the Caribbean regional average. The income indicator is virtually flat at 66.3, while the inequality score is remarkably low (at 15.7, falling from a high of 37.4 in 2002)—23.4 points below the regional average. This is a result of structural low growth, but also of the fact that Mexico had the worst post-pandemic recovery in North America and among the main economies in Latin America.

Mexico’s growth trajectory has not been volatile but rather the challenge has been stubbornly low growth relative to its potential. Data from the International Monetary Fund show an average 2.08 percent year-over-year (YoY) growth since 1990; this compares to 4.3 percent for Chile, 4.2 percent in Peru, 3.4 percent in Colombia, 2.6 percent in Argentina, and 2.3 percent in Brazil—some of whom have experienced very volatile growth trajectories. Unleashing further growth has come as a challenge, despite a sophisticated export sector, sound macroeconomic policy and a resilient private sector. This can be partly explained by the fact that investment as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) has for many years lagged behind its regional peers, remaining below 25 percent for most years since the 1990s, even dipping below 20 percent in 2019, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). However, some positive signs have emerged, with investment reaching 24.9 percent of GDP in the second quarter of 2023, and a more favorable external environment and positive trends such as nearshoring leading to an increase in private sector investment of 18.1 percent YoY in the first half of 2023, the largest increase since 1993.

Productivity is also an issue. Economy-wide labor productivity and overall productivity lag behind other emerging market G20 economies such as South Korea, Turkey, and Thailand.

The economic liberalization of the country in the 1980s and 1990s—which led to North American economic integration, a sound financial sector, and a much more complex economy—has greatly benefited Mexico, but its impact has not been felt by all regions, sectors, and groups. To put this in perspective, the average growth of the northern and central parts of the country reached 3.1 percent YoY between 2010 and 2019 according to Banxico data, and only 0.06 percent in the south, where most of the country’s marginalized population lives. At the same time, the large proportion of informally employed workers—55 percent of the labor force according to the 2023 labor force survey, only a slight decrease from the 2005 figure of 59 percent—is also a key driver of the inequality gap. Regional gaps in growth and informality contribute to drastically different levels of vulnerability and access to services. For example, states in the north like Baja California Sur, Baja California, and Nuevo León had the lowest percentage of multidimensional poverty as a share of their population in 2022 according to the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) (13.3 percent, 13.4 percent, and 16 percent respectively), while multidimensional poverty rates are significantly higher in the southeast with Chiapas, Guerrero, and Oaxaca (67.4 percent, 60.4 percent, and 58.4 percent respectively) topping the list.

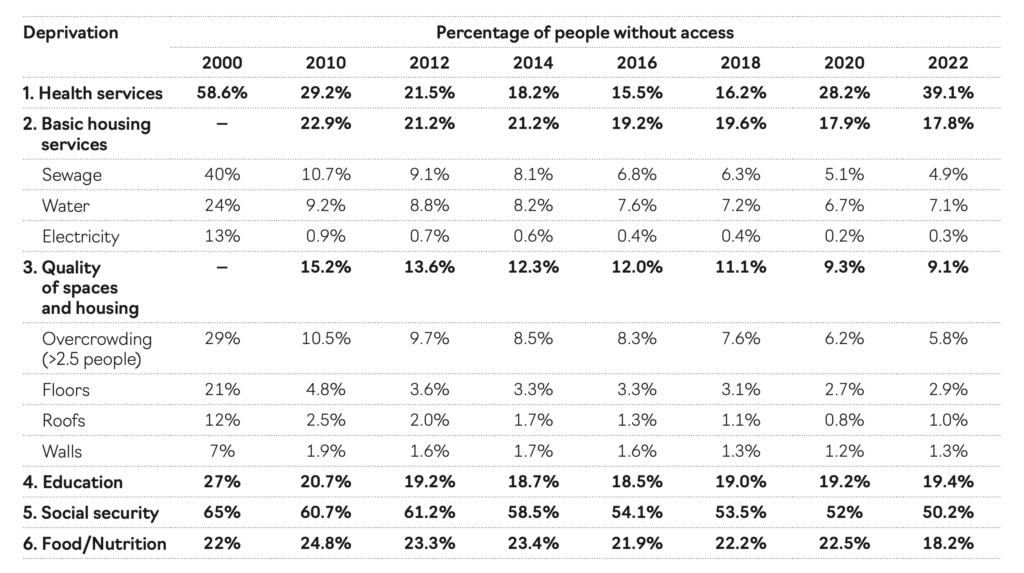

That said, Mexico has made advances with respect to specific social indicators. For instance, the Index highlights significant improvements in education since 2000 (from 27.7 points to 48.1), although health has experienced an enormous decline of more than 5 points since then, dropping back to 78.1 points. Moreover, as the CONEVAL chart in Table 1 shows, the reduction of access to health between 2020 and 2022 happened at the worst possible time: the COVID-19 pandemic.

If we understand prosperity as the absence of social “lacks” (i.e., people’s needs are met), according to the country’s multidimensional measurement of poverty, Mexico has seen relevant improvements for several years, in spite of its low average growth. One of the reasons this has been possible is that there is now an anchor with which to assess the evolution of access to a “sufficient” income, to food and nutrition, health, education, social security, housing and services. Being capable of rigorous measurement helps align institutional aims and policies, which are in turn a prerequisite to effectively address lacks or shortfalls, and promote inclusion and prosperity. The other two vertices of the “prosperity triangle” are strong and sustained economic growth, and sound policies, which have not always been present.

While economic growth over the last five years has averaged just 0.63 percent per year, Mexico has managed to reduce poverty significantly. It has done so by almost quadrupling social program spending from US$8 billion in 2018 to US$30 billion in 2024, and increasing the minimum wage across the country (2018–24) by 182 percent—and by 324 percent in the “free border zone.”

Table 1. Change in deprivations in Mexico (2000-2022)

The future ahead

Mexico continues to preserve key technical and autonomous institutions, which have so far made it resilient to various affronts to political, legal, and economic freedoms, and which have helped the country sustain a basic level of prosperity, as reflected by the Index. However, the negative developments in some indicators should serve as early warning signs, while also pointing to the path forward, if the country wants to advance towards the next stage in democratic consolidation and progress in well-being standards.

The insights above suggest there is a clear path toward Mexico’s advancement on both the freedom and prosperity fronts. These can be summarized in three clear pillars: strong institutions, strong and sustained growth, and well-articulated and effective redistribution policies.

Mexico has a unique opportunity to capitalize on the current favorable external environment and attract investment that can serve as a pull factor for growth. Its sustainability will largely depend on productivity improvements, including to education, reskilling, infrastructure, and energy. The country remains a bastion of free trade in Latin America and holds a strong strategic position, being the United States’ largest trading partner. Amid US-China decoupling, gains from nearshoring could be significant. For the time being, this trend lays more in the expectation than the materialization front. According to Alfaro and Chor, Mexico is sixth in the list of countries to have derived the most market gains from the decoupling of the United States from China between 2017 and 2022. It should be in the top two.

Enormous expectations cannot cohere into more significant material investment commitments if the institutional framework continues to weaken, and this is one of the key risks that could lead to a further deterioration in Mexico’s Index rankings. In many ways, Mexico has de jure maintained the institutions and legal framework to support political, economic, and legal freedoms, including an independent central bank, an autonomous Supreme Court, and an independent National Electoral Institute. But a de facto deterioration is clearly occurring—in the form of political loyalists being appointed to key autonomous institutions, budget and staff cuts, a concentration of power, and a militarization of strategic economic activities. This cycle of deterioration is a risk to freedoms and prosperity in the near term.

In this sense, pendular politics also remains a significant risk, both to institutions and to sound evidence-based policymaking. The country will head to the polls in June 2024 and the signs of polarization are increasing. While disagreement and debate are essential components of a healthy democracy, the current discourse in the country is anything but constructive; and uncertain and ad hoc shifts in policy risk squandering the opportunities to attain strong and sustained growth, as well as improvements in prosperity more broadly.

Undermining institutions, pendular policies, militarization, the absence of solid foundations for strong and durable economic growth, and growing fiscal pressures, are a recipe for failure. On the contrary, policies aimed at strengthening and perfecting our institutional scaffolding, delivering good and sustained policies, ensuring the rule of law, improving competitiveness, enhancing productivity, and maintaining a sound fiscal stance, could make Mexico a success story, grounded on improved freedom and increased prosperity.

Vanessa Rubio-Márquez is professor in practice and associate dean for extended education, at the School of Public Policy, London School of Economics; associate fellow at Chatham House; consultant and independent board member. She is a member of the Freedom and Prosperity Advisory Council at the Atlantic Council. Vanessa had a twenty-five-year career in Mexico’s public sector, including serving as three-times deputy minister (Finance, Social Development, and Foreign Affairs) and senator.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: A woman wearing a traditional dress takes a selfie with a person wearing a "Parachico" traditional dance costume during the Chiapas Grand Festival in Chiapa de Corzo, Mexico January 20, 2024. REUTERS/Jacob Garcia