On prosperity, Taiwan ranks high—but its future hinges on Chinese power plays

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

Taiwan’s diplomacy stresses its peaceful transition from a single-party authoritarian state under the Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang (KMT), to a robust democracy with strong protections of civil and political rights. It identifies as a “beacon of democracy,” especially in East Asia, a region in which democracy has not been the predominant political form historically. The time coverage of the Freedom Index, 1995–2023, is well-suited to analyze Taiwan’s contemporary institutional evolution, and our survey findings support Taiwan’s self-image as a liberal democracy.

Binary indexes of democracy, such as the Boix-Miller-Rosato (BMR) or the Democracy Dictatorship Index, identify 1996 as the year of Taiwan’s democratic transition, but the transition away from the authoritarian system that had existed in Taiwan since 1945 was as early as the late 1970s. As pressure from below demanding steps towards greater political openness intensified in the 1980s, the KMT-led authoritarian regime grew increasingly tolerant of dissent, allowing the democratization process to move forward.

A key factor behind the regime’s changing attitude toward democratization was Taiwan’s deepening isolation as leading countries, including the United States, abandoned the view that Taiwan’s “Republic of China (ROC)” state represented all of China and shifted recognition to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Some key inflection points included the lifting of the “Temporary Provisions for the Suppression of the Communist Rebellion” in 1991, which had originally been enacted as a constitutional amendment in 1948. This was accompanied by a series of increasingly significant elections, including the first comprehensive elections for the National Assembly (1991) and Legislative Yuan (1992), as well as the first direct election of a Taiwan Provincial Governor (1994).

While Taiwan’s democratization was an incremental process, 1996 is generally seen as the crucial milestone in Taiwan’s political history, for that year saw its first direct presidential election. The victor was the incumbent, Lee Teng-hui, the candidate of the former authoritarian regime’s ruling party, the KMT. Lee’s strong performance—he won more than 50 percent of the vote in a four-way race—benefitted from his decision to align himself with the democratic transition. His election also helped to marginalize those in the KMT who took a more skeptical view of democracy. The political subindex, based on the continuous measure of democracy produced by the V-Dem project, likely reflects the slow adoption of democratic values by those who saw their political dominance eroding under the new rules of the game.

Taiwan’s democracy took another big step forward in 2000. In that year, the index jumps to a level comparable to that of well-established democracies in Europe and North America. The Index reflects the first turnover of power in the new democracy following the victory of the opposition Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) presidential candidate, Chen Shui-bian. The opposition party’s first national election victory marks the completion of the democratic transition of Taiwan, which since then has experienced only small, incremental changes in political freedom in areas such as women’s representation and protection of minorities.

Nonetheless, the political subindex components point to some features of Taiwan’s political and constitutional architecture that lag behind more established democracies. Most saliently, the component measuring the degree of legislative constraint on the executive receives a significantly lower score than the rest of the components, and presents a greater volatility throughout the period of analysis. I believe this discrepancy reflects the awkwardness of Taiwan’s quasi-presidential constitutional system. The head of state (president) is separately elected for a fixed term, giving him or her a popular mandate. This important role coexists with a standard parliamentary system in the legislature. The president appoints the head of government (premier), and while legislative confirmation is not required, the legislature can remove the premier with a vote of no confidence, which triggers new legislative elections. Since 1996, Taiwanese politics have been characterized by a constant debate about the relative powers of the presidency versus the legislature and premier. This challenge recedes during periods of unified government (2008–16, 2016–24), when the president takes the leading role, but it reemerges in periods of divided government (2000–08, 2024 to the present).

The legislative constraints indicator closely reflects the two parties’ relative strength in these two branches of power. From 2000 to 2008, the DPP held the presidency but the KMT had a majority in the legislature, leaving President Chen Shui-bian struggling to implement his domestic agenda. In 2008, the country returned to unified government under President Ma Ying-jeou, with the KMT holding both the presidency and the legislative majority. While Ma faced a surprisingly feisty legislative leadership, the legislature was still much more deferential to presidential power than had been the case under Chen. The small ups and downs in the indicator since 2016—a period of unified government under DPP President Tsai Ing-wen—reflect the ongoing search for a stable balance of legislative and executive power. Indeed, when Taiwan returned to divided government in 2024, the KMT-led legislature immediately proposed reforms aimed at constraining the presidency.

Taiwan’s scores on two other components of the political subindex are low compared to other measures and require explanation. First, the score for political rights of association and expression is lower than might be expected, in part because the two main political parties tend to exploit the popularity of democracy to achieve a political edge. Both parties, when they were out of power, accused their opponents of reviving undemocratic practices, including politically motivated prosecutions of party leaders and officials. In fact, accusations of corruption have been used to sideline politicians, especially after they leave office. Chen Shui-bian’s conviction on bribery charges in 2009 is a clear example of this practice.

Second, Taiwan imposes restrictions on media ownership, a practice which is reflected in the political rights component of the Index. Some Taiwanese see these restrictions as an effort to deny certain political views access to the media. However, others believe they are necessary to prevent the Beijing government from influencing mass media in Taiwan. In particular, the visible drop on this measure starting in 2020 probably captures the National Communications Commission’s decision not to renew the TV license of Chung T’ien Television. Chung T’ien was widely believed to be a mouthpiece for Beijing whose news coverage was biased against the DPP and in favor of KMT, which argues for more favorable relations with the PRC.

Turning now to the economic subindex, Taiwan has a long history of strong performance in terms of economic freedom. It is clear that the component measuring women’s economic freedom is the main factor driving the overall positive trend since 1995, and especially until 2004, with an extraordinary increase of more than thirty points. Half of this increase takes place in 2003, reflecting the improvement in legislation regarding workplace conditions for women, mainly in the areas of nondiscrimination, sexual-harassment prevention, and maternity leave conditions. Other important advances include granting equal treatment for men and women regarding asset holdings in 2004, and equal access to industrial and dangerous jobs in 2015. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the overall high degree of gender equality in the public sphere is not always accompanied by a similar level of equality in the private domain. Taiwanese women still carry a disproportionate share of household work, as well as other burdens typical in strongly patriarchal societies.

The indicators of trade and investment freedom seem to be highly sensitive to Taiwan’s relationship with mainland China. In particular, the large movements in investment freedom (2005, 2015, 2017, and 2022) reflect changes in cross-Strait investment regulations that alternately ease and tighten the conditions for PRC-Taiwan capital flows. Similarly, the seven-point drop in trade freedom in the early 2000s is likely a product of stricter restrictions for export and import of goods and services with China. As the concluding section details, China poses a significant threat to Taiwan’s democracy. Anxiety about how economic interactions could make Taiwan vulnerable to PRC economic coercion explains why Taiwan’s trade and investment policies have not moved consistently in the direction of greater openness. If we could exclude the China element from these indicators, I assess that Taiwan’s scores would be a lot smoother, reflecting a sustained commitment to fairly open trade and capital movement with the rest of the world.

The rule of law in Taiwan, as measured by the legal subindex, has experienced a mild increase since the year 2000, mainly driven by notable increases in improving bureaucratic quality, control of corruption, and informality. The democratization process very significantly improved the level of accountability for political leaders and public officials at large, improving the overall capacity and efficiency of the public sector to enforce and abide by the law. Judicial effectiveness and independence is an important factor contributing to this development, and the fact that the score on this area is relatively high since the year 2000 certainly captures the reality of the situation in Taiwan. My intuition is that the transitory dip in the 2008–16 period is due to what people perceive to be politically motivated prosecutions of politicians, a perception that was particularly acute in the immediate aftermath of Chen Shui-bian’s presidency.

Two more insights are worth mentioning. On one hand, the visible fall in clarity of the law between 2012 and 2016 can only be explained by an aggravation of the discussions regarding the balance of power between the presidency and the legislature in a period of intense partisan competition and outside-the-system political mobilization. Efforts to use constitutional revision to settle these disputes necessarily introduce uncertainty about the legal system.

On the other hand, Taiwan’s security score experienced a sharp decline of over ten points between 1996 and 2000. While this component has fluctuated since 2000, it remains below its 1995 level. I believe it would be a mistake to attribute this decline to domestic factors. Taiwan continues to be a safe society with low rates of crime. The timing of fluctuations in the security component suggest it is highly sensitive to Taiwan’s citizens’ feelings of insecurity relative to the PRC’s military threat. The drop in the security score during the Lee Teng-hui and Chen Shui-bian presidencies (1996–2008) reflects the increase in PRC political and military pressure on Taiwan, beginning with its military exercises at the time of the 1996 elections. While the PRC paused some of its pressure on Taiwan during Ma Ying-jeou’s presidency (2008–16), the sense of threat has steadily increased over the first quarter of the century.

Evolution of prosperity

The evolution of Taiwan’s Prosperity Index score is somewhat easier to analyze, as the positive overall trend since 1995 is mainly driven by economic and health outcomes, but nonetheless there are some interesting takeaways from the analysis of the different components.

Taiwan’s economic success story is well known, with impressive and sustained gross domestic product (GDP) per capita growth numbers for several decades now. The income component of the Prosperity Index not only reflects this fact, but also the limited negative effects of the last two large global crises, namely, the Great Recession of 2008–09 and the COVID-19 pandemic. The Taiwanese economy has proven resilient and mature, despite a very profound transformation from a developmental state with a relatively high level of state intervention to a much more deregulated market economy.

Despite Taiwan’s strong growth, inequality has increased over recent decades, from a very low base in the early years of our study. Rising inequality is due in part to the structural changes in terms of economic policy mentioned above, together with a weak legal environment for unionization. Other forces driving incomes in a more unequal direction include the offshoring of traditional manufacturing after 1987, primarily to mainland China, and an economy increasingly bifurcated between the domestic-facing retail and service sectors and an export-oriented high-tech sector. Despite the decline in performance in eradicating inequality, Taiwan still maintains a more equitable income distribution compared to the United States and China. Its Gini coefficient, around eighty in recent years, remains higher than the East Asia and Pacific regional average (66), mainland China (56.5), and the United States(65.3).

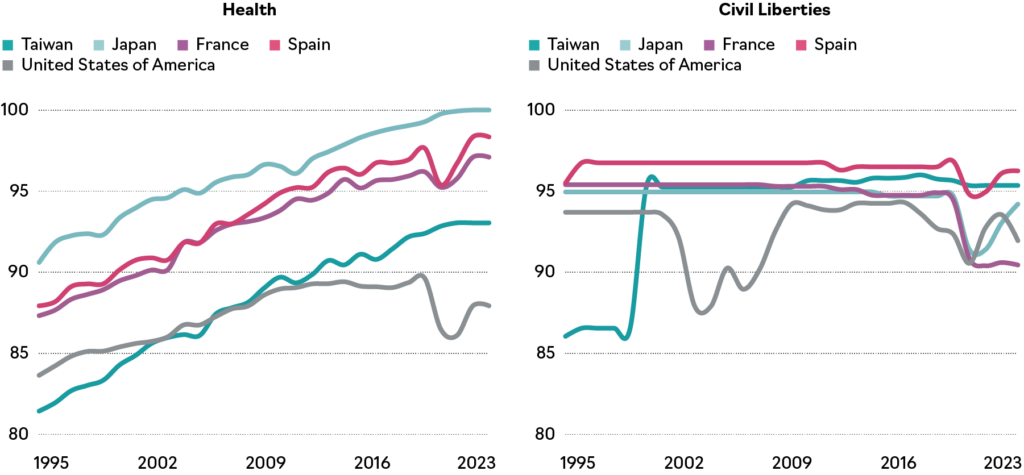

Regarding health, Taiwan is among the top performers in the world, increasing its score by more than ten points since 1995, when the country adopted a universal health insurance scheme. The recent evolution of the health indicator in Taiwan contrasts sharply with that of other developed countries, especially when it comes to its handling of the COVID-19 crisis. Taiwan managed the health emergency better than virtually any other country of the world, closing its borders very early, requiring quarantine for everyone entering the country, implementing a state takeover of mask production and distribution, requiring masks in public, and accelerating the production and implementation of vaccinations. As a result, COVID-19 did not spread in Taiwan until the vaccines were available, and the death toll from the pandemic is negligible in the health indicator, unlike European countries and the United States (Figure 1). It is certainly true that other countries, especially Asian developed nations like Japan, were also capable of containing the negative public health effects of the pandemic. Nonetheless, the really distinctive feature of Taiwan is that it was able to do so without a major erosion, even if shortlived, of civil liberties of its citizens (Figure 1). There were restrictions in Taiwan, but the limitations on individual freedom were drastically lower than in other developed countries, and did not require draconian enforcement thanks to the generalized voluntary compliance of the population.

Freedom and Prosperity Indexes, Atlantic Council (2024)

Finally, the dynamics of the minorities component are complex and require interpretation. The sharp increase in the year 2000, coinciding with the first DPP presidency, surely reflects the substantial improvement of the indigenous Taiwanese population in terms of access to public services, jobs, and opportunities. On the contrary, the fall in the score in the last five years is probably explained by the situation of migrant workers, whose numbers have increased significantly in the recent period, and whose legal status and conditions have not been as well protected as those of domestic workers. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, some foreign workers were confined to their workplaces for long periods of time, while most Taiwanese enjoyed a relatively normal lifestyle with few pandemic-related limitations on their day-to-day activities.

The path forward

Taiwan’s democratic institutions have functioned smoothly for nearly three decades. After eight rounds of presidential elections and even more of legislative and local elections, campaigning and voting in competitive, multiparty elections is routine. Taiwanese also enjoy a high degree of protection for their civil rights, in realms ranging from freedom of speech to marriage equality for LGBTQ+ couples. While all democracies have their flaws— Richard Bush’s book Difficult Choices outlines many of Taiwan’s—the island’s political system seems to meet the conventional definition of a consolidated democracy: democracy is, indeed, the “only game in town.”1Richard C. Bush, Difficult Choices: Taiwan’s Quest for Security and the Good Life (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2021).

Perhaps the best evidence of the strength of Taiwan’s democracy is its citizens’ tendency to view it as the defining trait that makes Taiwan Taiwan, and differentiates it from the People’s Republic of China.

With the exception of indigenous Taiwanese, who constitute a little over 2 percent of the population, the people of Taiwan are descended from settlers from mainland China. Their ancestors arrived over several centuries, including a long wave of migration between the late sixteenth and late nineteenth centuries and a short wave between 1945 and 1949. From 1895 to 1945 Taiwan was colonized by the Japanese empire.

For most of its history, Taiwanese were subjects of empires and states that controlled the island from afar. When the ROC took control of the island at the end of World War II, the new government expected Taiwan to uphold its goal of merging Taiwan into the Chinese state on the mainland. Even after the ROC lost the civil war and the PRC was founded in 1949, the ROC government continued to insist that “recovering the mainland” was its destiny, and Taiwanese should work toward restoring the ROC in the mainland. The PRC, too, believes in merging Taiwan into China, but its policy is that the Chinese state Taiwan should join is the PRC.

The advent of democracy in the 1990s opened the possibility of a different destiny for Taiwan. Some Taiwanese even called for formal independence from China—for abandoning the “ROC” label and eschewing forever the possibility of merging into a mainland-based nation. Some made the case for independence on the grounds that Taiwan is not “Chinese.” Advocates of Taiwanese cultural nationalism argued that, despite their Chinese ancestry, Taiwan’s culture is an amalgam of indigenous, Japanese, and Western influences that differentiate it from China.

No matter how the case for independence is made, however, the PRC government has made it clear that it will oppose such a move with military force, so the idea of formal independence has lost much of its support in Taiwan.

At the same time, Beijing’s pressure on Taiwan to allow itself to be absorbed into the PRC was intensifying, Taiwan’s political and social institutions were becoming freer and more democratic. Meanwhile, despite Beijing’s efforts to promote the idea, support for unification within Taiwan has dwindled. And the mainstream rationale for Taiwan’s separate status has shifted from cultural nationalism to a sense of civic nationalism—the idea that what makes Taiwan unique—and unification unwelcome—is the island’s liberal democratic political system. Democracy, warts and all, has become a point of pride and distinction for Taiwanese, which should make for a bright projection for its continued thriving in Taiwan.

Unfortunately, the future of democracy on the island does not depend on the Taiwanese people alone. The PRC opposes both Taiwan’s continued self-government and its democratic system. In Beijing’s view, Taiwan’s historic connections to the Chinese mainland make it an inseparable part of “China,” and as the PRC state is the current government of China, Taiwan must, sooner or later, be incorporated into the PRC. There’s no chance that the PRC would adopt Taiwan’s liberal democratic institutions and practices, so unification would almost certainly bring an end to democracy in Taiwan, as it has in Hong Kong.

How likely is this outcome? It is impossible to predict, but the PRC is determined to bring Taiwan to heel, peacefully if possible, but by force if necessary. So far, the two sides have managed to avoid conflict, in part because the costs and risks of forcible unification are high, and in part because Beijing believes it can prevail without force eventually. I think it is likely that this stalemate will continue in the near future. If it does continue for the next five to ten years, the situation may evolve to a point where a mutually acceptable arrangement is possible. Or it may not, in which case Taiwan’s democracy will continue to exist under constant threat.

Taiwan’s prosperity is similarly dependent on external factors. The high-tech boom that followed the offshoring of traditional manufacturing in the late 1980s and the 1990s has made Taiwan more important than ever in the global economy. The IT manufacturing ecosystem—of which the semiconductor giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is only the most famous of many critically important firms—has made Taiwan more central to the global economy than ever. Regional and global supply chains connect Taiwan to partners in Japan, Korea, the United States, the PRC, and more, as well as to customers around the world.

The mutual benefit derived from these relationships is an important deterrent to military conflict in the Taiwan Strait—Beijing has everything to lose, economically, if these economic relationships are disrupted. Beijing thus faces a dilemma: realizing its goal of unification could undercut its economic success, but avoiding that outcome means tolerating a political status quo in the Taiwan Strait that the PRC leadership has defined as unacceptable. As long as Taiwan continues to act with restraint— avoiding creating the perception that unification has become impossible—the economic benefit of tolerating the status quo will probably outweigh the political cost. Still, any of these factors could shift unexpectedly, with the likely result that both democracy and prosperity in Taiwan would take a tragic turn.

Shelley Rigger is Brown professor of East Asian Politics and vice president for academic affairs/ dean of faculty at Davidson College. Rigger has a PhD in government from Harvard University and a BA from Princeton University. Rigger is the author of two books on Taiwan’s domestic politics, Politics in Taiwan: Voting for Democracy (Routledge 1999) and From Opposition to Power: Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (Lynne Rienner Publishers 2001). She has published two books for general readers, Why Taiwan Matters: Small Island, Global Powerhouse (2011) and The Tiger Leading the Dragon: How Taiwan Propelled China’s Economic Rise (2021).

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous Edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the data

About the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: People shop at a Lunar New Year market in Taipei, Taiwan February 4, 2024. REUTERS/Ann Wang

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media