Pakistan faces urgent need for comprehensive reforms to spur long-term growth and stability

Table of contents

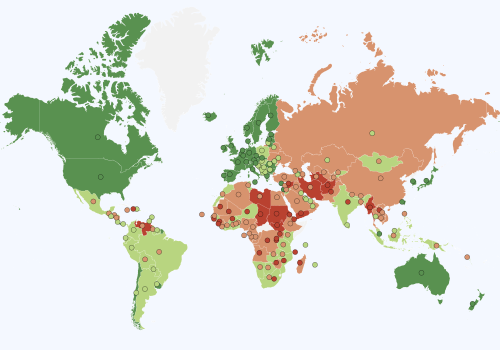

Evolution of freedom

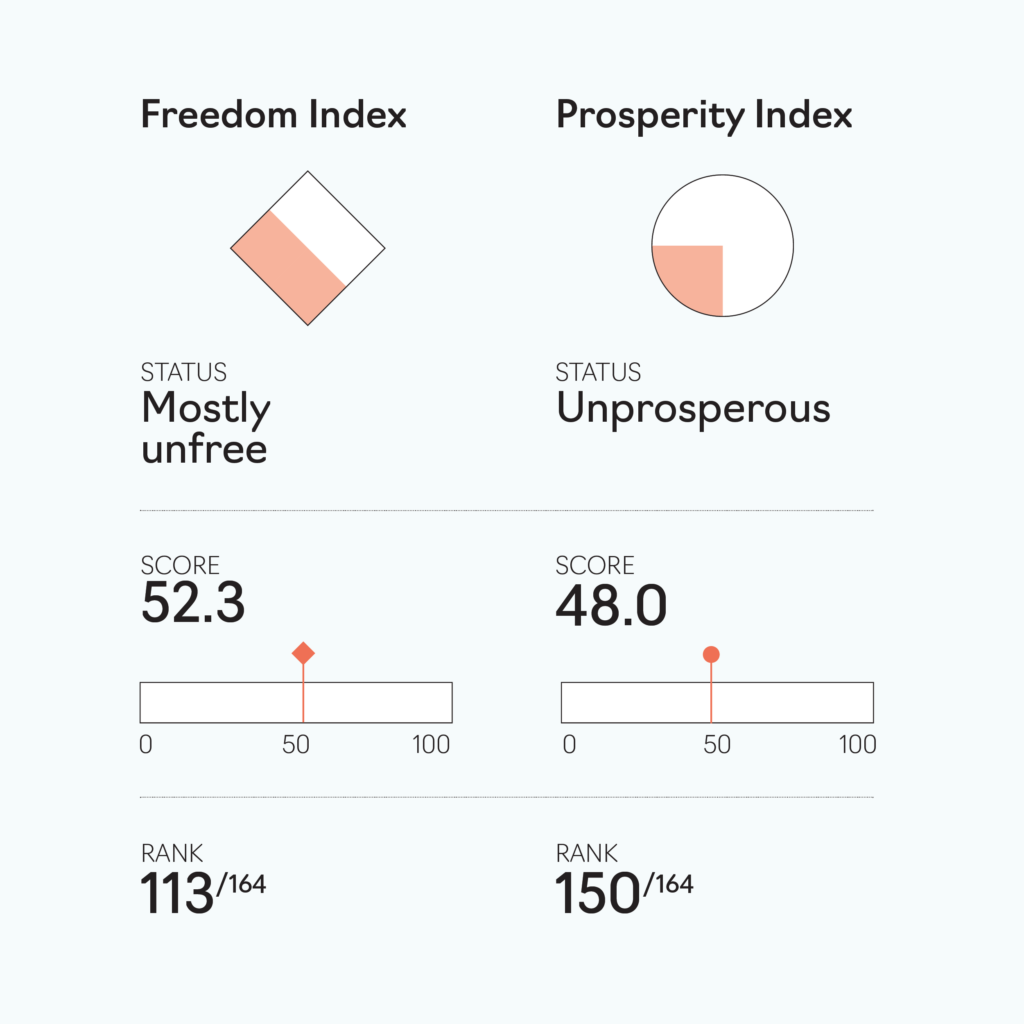

The change in Pakistan’s Freedom Index during the last twenty-five years suggests a positive association between freedom and civilian democratic rule. The Index was at its lowest level during the period of authoritarian rule between 1999 and 2008. It fell below the South and Central Asian average at the beginning of this period and remained below it for the greater part of this century, recently recovering and rising above the regional average due to a sharp increase in 2021. This steep rise in the Index runs counter to the established narrative among political scientists and journalists, that highlights a deterioration in freedom in the country during this period. This dissonance can be partly reconciled by taking a closer look at the different indicators of the Freedom Index, though it also underscores the need for better measurement.

Pakistan’s above-average performance on the Freedom Index relative to its regional comparators is an artifact of the sharp rise in the economic and political freedom subindices in the recent past. The steep rise in the country’s Freedom Index is in large part due to a 10-point increase in economic freedom since 2014. Although Pakistan’s level of trade openness has been high since the turn of the century, its investment freedom deteriorated between 1999 and 2014. The sharp rebound in the country’s investment freedom since 2014 appears to capture the introduction of the 2013 Investment Policy, which liberalized the foreign investment regime. This policy increased the freedom to invest by opening sectors and activities for foreign investment, strengthening protection against both indirect and direct forms of expropriation, and by allowing for the full repatriation of profits.

However, a closer analysis of the indicators of the economic freedom subindex shows that the country is a regional laggard on property rights protection. On this indicator, Pakistan’s scores have been among the lowest in the region this century, and remained well below the regional average in 2022. The dearth of property rights protections is manifest in Pakistan’s high perceived risk of expropriation in the country risk rankings published by international credit insurance groups.1See, for example, the Credendo risk assessments at https://credendo.com/en/country-risk/asia. The country does particularly badly on currency inconvertibility and transfer restriction risks, and has moderate to high expropriation risks. In addition, investor surveys in Pakistan report an environment of weak contract enforcement with long (three- to five-year) delays in the resolution of commercial disputes.2State Bank of Pakistan, Annual Report 2018-2019 (The State of the Economy), 2019, https://www.sbp.org.pk/reports/annual/arFY19/Anul-index-eng-19.htm. Therefore, Pakistan’s steady rise in economic freedom is largely due to the liberalization of investment policy, which was, however, underpinned by weak property rights protection and ineffective contract enforcement.

The rise in political freedom is the other trend behind the improvement in the country’s Freedom Index. The main indicator driving this improvement is legislative constraints on the executive, which appears to be measuring the strength of opposition parties in parliament during the period of civilian rule (2008–22). Within this period, the legislative constraints indicator is higher during periods of coalition government (2008–13 and 2018–22) and lower during 2013–18 when the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) had an effective majority in parliament. The steep rise in the constraints on the executive post-2021 appears to be capturing the removal of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government in 2022 through a parliamentary vote of no confidence. However, a different picture emerges if we use an alternative measure of the constraints on the executive: the executive’s ability to bypass parliamentary scrutiny by enacting laws through presidential ordinances. This measure shows that the coalition governments since 2018 passed almost the same number of ordinances as Musharraf’s authoritarian government, which highlights the ease with which minority governments were able to bypass parliament during the period when the constraints on the executive indicator was rising sharply. So it appears that the methodology used by the Freedom Index is overestimating the constraints on the executive: an important component of political freedom. This suggests the need for improved measures of constraints on the executive in contexts where the executive has the ability to use exceptional constitutional measures to bypass parliament at low political cost.

The deterioration of political rights—another indicator of political freedom—on this Index after 2012 and its reversal and sharp rise since 2019 also run counter to political events in Pakistan. The period since 2012 saw the emergence of PTI, a major new federal political party in Pakistan that was able to grow its electoral base and form a provincial government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) in 2013. While the results of the 2013 election were politically and legally contested by PTI, the fact that a major new party was able to grow in Pakistan after twenty years of authoritarian and contested politics suggests that rights to political association and expression were robust, and hence it is difficult to understand the measured deterioration in political rights between 2013 and 2018. Furthermore, the increasing rate of arrests and detentions of opposition politicians in Pakistan since 2018 on the grounds of corruption and creating threats to public order is suggestive of a partisan bias in executive-led accountability, and appears to reflect a weakening of political rights during this period. Similarly, the sharp improvement in the civil liberties indicator—another part of the political freedom subindex—in the last few years, runs counter to the steady deterioration in Pakistan’s World Press Freedom Index during the past five years.3Reporters Without Borders, “2023 World Press Freedom Index – journalism threatened by fake content industry,” the 2023 World Press Freedom Index, https://rsf.org/en/2023-world-press-freedom-index-journalism-threatened-fake-content-industry. These inconsistencies suggest the need for more thorough indicators to measure the strength of political rights and civil liberties.

An important challenge for Pakistan has been its high levels of perceived political risk. This reflects growing political polarization in Pakistan since 2013, with successive opposition parties raising concerns about the fairness of the electoral process. Political polarization is also manifesting itself in an increasing tendency of political parties to use the superior courts to dispute fundamental constitutional precepts, a trend that is having adverse effects on the country’s perceived risk of political instability. Hence, the Pakistan experience highlights the need to measure and include political polarization and partisan conflicts as components of the political freedom subindex.

Another challenge for Pakistan is its low score on legal freedom. The U-shape evolution of this subindex seems to be mainly driven by the security indicator, which decreased significantly after the 9/11 attacks of 2001, but has recovered since 2011. Another important change identifiable in the data is the improvement in judicial independence in the aftermath of the lawyers’ movement of 2007–09, which created greater space for the exercise of independent authority by the judiciary. However, the deterioration in judicial independence scores during the last decade is a concerning trend. Along with this, the indicator scores within the legal freedom subindex show that the level of corruption, bureaucratic quality, and state capacity overall rep- resent important drags on Pakistan’s development.

From freedom to prosperity

Pakistan’s prosperity score lags well behind other economies in the region. The income indicator of the Prosperity Index—which uses gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in constant 2017 US dollars as a measure of income—shows that, after being an above average performer in the region, Pakistan’s economy fell behind and began to diverge from its comparators during the earlier part of the century. Worryingly, there does not seem to be any indication of catch-up: the country’s economy has been growing at a slower rate than its peers during the past decade. The recent literature attributes poor growth performance to weak productivity and an inability to compete in external markets, low rates of investment, slow rates of structural change, and the country’s inability to harness the potential of educated women because of large gender gaps in economic participation.4World Bank Group, From Swimming in Sand to High and Sustainable Growth: A roadmap to reduce distortions in the allocation of resources and talent in the Pakistani economy. Pakistan’s Country Economic Memorandum 2022, https://documents1.worldbank.org/ curated/en/099820410112267354/pdf/P1749040fc80a70ca0b6f70f7860c4a1034.pdf.

Pakistan’s low score on the Prosperity Index is also underpinned by poor scores on the education, health, and environmental quality indicators, relative to other countries in the region. The gap in Pakistan’s education performance is particularly staggering, with an education score that is one-third the regional average. The country’s health and environment scores also remained below the regional average in 2022. It is important to note that comparing Pakistan to other countries in the region will underestimate Pakistan’s environmental challenges because the University of Chicago’s Air Quality Life Index shows that northern South Asia has among the poorest air quality scores globally. That is to say, Pakistan is not only underperforming regionally, it is underperforming globally.

The inequality indicator shows that Pakistan is doing much better in terms of equality than the regional average. This seems to reflect the distributive dividends that are accruing due to Pakistan’s high reliance on foreign remittances. However, inclusive development remains an unfulfilled goal because of Pakistan’s poor performance in terms of minority rights and its low score on women’s economic freedom.

There are several ways in which weak performance on the indicators of the Freedom Index inhibits prosperity. Investor surveys identify the high perceived risk of expropriation (reflected in Pakistan’s low property rights protection scores) as an important cause of Pakistan’s low investment rates, which are among the lowest in the region. Challenges of state capacity—captured by the scores on bureaucratic quality and corruption—and relatively low levels of public investment in education, health, and environmental sustainability all contribute to poor environmental and social outcomes. Low levels of public investment are a consequence of a weak fiscal compact, with the country having one of the lowest levels of tax utilization in the East Asia & the Pacific region. Recent studies also show that Pakistan’s relatively poor performance on women’s economic freedom—a consequence of gender inequalities, labor market frictions, and restrictive gender norms—is adversely impacting prosperity.5World Bank Group, From Swimming in Sand to High and Sustainable Growth.

The future ahead

It is difficult to see how long-run growth rates and prosperity will improve in Pakistan without large-scale economic and institutional reforms. If Pakistan hopes to increase investment rates, it will require a radical reform of the country’s property rights and contract enforcement regimes to lower the perceived risk of expropriation. Pakistan’s path to prosperity also requires higher levels of public investment in education, health, and environment and climate resilience. This will not be possible without strengthening state capacity in the country and introducing radical reforms to improve bureaucratic quality. In addition, Pakistan needs a strong fiscal compact, in which its elites are willing to finance public investments in education, health, and environmental protection through taxation, at levels that bring it in line with its comparators. The country also requires reforms of its tariff, taxation, and subsidy regimes to overcome the bias in the economic structure against the tradeable sectors and high-productivity activities.

Furthermore, inclusive growth will not be possible without stronger protection for minority communities and without introducing interventions that lower women’s risk of harassment and violence, reduce their cost of mobility and connectivity, and incentivize employers to employ women; all of which are important prerequisites for women’s increased economic participation.6Ali Cheema, Asim I. Khwaja, M. Farooq Naseer, and Jacob N. Shapiro, Glass Walls: Experimental Evidence on Constraints Faced by Women in Accessing Valuable Skilling Opportunities, (Harvard: August 24, 2023), https://khwaja.scholar.harvard.edu/sites/projects.iq.harvard.edu/ files/asimkhwaja/files/glass_walls_paper_08_24_2023.pdf; Erica Field and Kate Vyborny, “Female labor force participation in Asia: Pakistan country study,” (summary by Sakiko Tanaka and Maricor Muzones; ADB Briefs no. 70, Asian Development Bank, Economics Working Paper Series, 2016), https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/209661/female-labor-force-participation-pakistan.pdf; World Bank Group, From Swimming in Sand to High and Sustainable Growth.

However, growing political polarization in the country poses a fundamental challenge as it increases the perceived risk of political instability, which, in turn, shortens the time horizons of the governing elite. The only way to address this challenge is to create a new political settlement that develops a consensus within and between the political and the governing elites, over the basic rules of the game and transitions of power. This is critical because large-scale reforms will take time to institutionalize, and this is not possible unless the political system enables the governing elite to develop sufficiently long time horizons. The political settlement must ensure inclusive power sharing, strong federal- ism, and regular and nondisruptive transitions of power. This is important to engender political stability in a fractured political system like Pakistan, where political party bases are fragmented across regional lines, and to develop sufficiently long time horizons that enable the governing elite to take political risks and introduce structural reforms that can generate increasing levels of income and prosperity.

Ali Cheema is an associate professor of economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences. His recent research combines experimental methods with qualitative analysis to study how political and wealth inequality shape representation, fiscal equity, and development the determinants of citizen trust and the role of gender norms and violence as barriers to women’s political and civic participation.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: People light candles, in commemoration of the victims of an attack on the Army Public School (APS) in 2014, in Karachi, Pakistan December 16, 2021. REUTERS/Akhtar Soomro