Poland’s democracy stands firm, but its economy faces headwinds

table of contents

Evolution of freedom

Poland, along with the three Baltic states, stands as one of history’s most remarkable examples of how embracing democratic institutions and a free-market economy can radically transform a nation and propel it onto a trajectory of rapid development. Following an unprecedented transition in 1989, Poland and other former communist bloc nations successfully established the three foundational pillars of a free society—rule of law, democracy, and market economy—guided by frameworks like the Freedom Index. Although the Index’s coverage begins only in 1995, when many key reforms were already implemented, Poland’s journey in the subsequent decades offers valuable insights. Notable milestones include its accession to the European Union (EU) in 2004 and, more recently, significant challenges to the rule of law starting in 2015, which is the primary focus of this piece.

The political shift following the 2015 parliamentary elections serves as an archetype of what might be called a “bad transition.” In such scenarios, authoritarian leaders or parties rise to power through legitimate electoral processes—a necessary but insufficient condition for true democracy—and proceed to systematically erode institutional independence, particularly within the justice system and civil service. The Law and Justice Party (PiS), under Jarosław Kaczyński’s leadership, secured a decisive victory in a fair election but quickly revealed its authoritarian tendencies. The sharp decline in political and legal subindexes from 2016 onward vividly illustrates this regression.

Among the political subindex components, the most severe deterioration occurred in political rights, driven largely by the PiS’s capture of public media, turning it into a propaganda tool. Fortunately, private media outlets managed to resist government pressure and served as a critical counterbalance.

However, the most dangerous attack came against the judiciary, as evidenced by the more than thirty-five-point drop in the judicial independence component within the legal subindex. Legislative changes in 2016 merged the roles of prosecutor-general and minister of justice, granting a political appointee sweeping powers over the judicial system, including appointments, promotions, and case allocations to specific prosecutors. This effectively undermined safeguards for prosecutorial independence, which allowed compliant prosecutors to be rewarded and dissenters punished. Judicial independence similarly eroded under politicized appointment processes.

Poland’s judicial system survived this assault primarily due to the vigorous defense mounted by civil society and advocacy groups. The rulings of the European Court of Justice in 2021 and 2023, alongside political pressure from the European Commission, played a crucial role, but these external interventions would likely have been insufficient without the active involvement of Polish non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and grassroots organizations.

PiS was unsuccessful in undermining the free elections, and those held in 2023 were democratic. The newly elected government has prioritized the restoration of judicial independence, a commitment that has led to the European Commission’s recent decision to terminate the Article 7(1) Treaty on European Union (TEU) procedure, citing that “there is no longer a clear risk of a serious breach of the rule of law in Poland.”

Turning to the economic subindex, several notable aspects deserve attention. From the early 1990s, the anticipation of eventual EU membership spurred a series of significant liberalizing reforms. Between Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004 and 2016, the country benefited from increasing policy credibility and access to the common market for trade and capital, driving a robust convergence process with other EU member states.

However, during the years of PiS governance, economic freedom suffered, primarily due to increased nationalizations and expansion of the state sector in the economy. Higher fiscal spending and growing budget deficits during this period Evolution of Prosperity further weighed on economic freedom, representing a clear drag on progress in this area.

Despite these challenges, the economic subindex reflects an overarching positive trajectory, largely attributed to a notable increase in women’s economic opportunities. A rare positive legacy of the socialist era is the strong foundation of gender equality within Polish society, particularly in economic participation. The sharp rise in this indicator in 2010 aligns with the adoption of European regulations promoting equal treatment—standards that were already a widespread practice in Poland.

Evolution of prosperity

The Polish economy has undergone a remarkable convergence with the EU. In 1990, Poland’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was less than 40 percent of the EU average. Over the past twenty-five years, this gap has significantly narrowed, reaching 83 percent of the EU average by 2023.

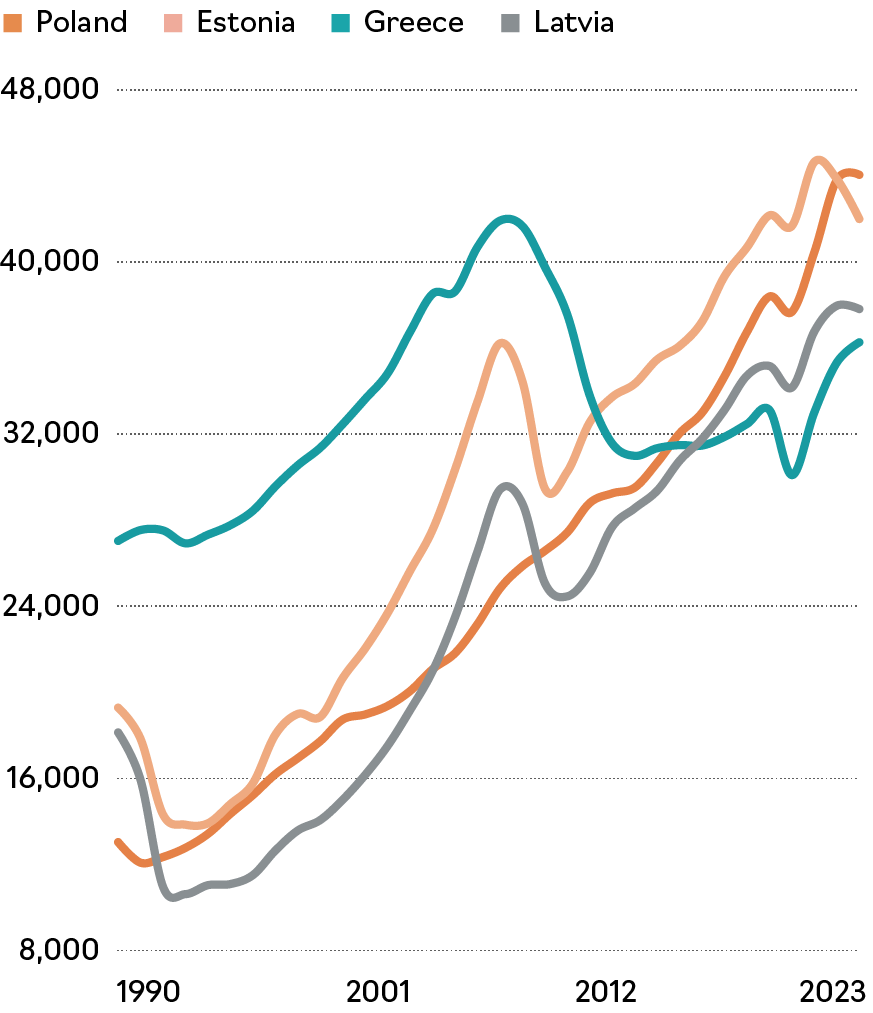

A notable aspect of Poland’s economic performance is its resilience during the 2008 financial crisis, which left no significant negative impact on the country’s economy. As illustrated in Figure 1, Poland’s GDP per capita growth remained consistently positive from 1992 until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, the financial crisis, followed by the debt crisis, had substantial repercussions in neighboring countries such as Estonia and Latvia, not to mention the severe impacts felt in Greece. Consequently, Poland today is wealthier than all these countries, despite having a lower GDP per capita than each of them in 2007.

Finally, it is worth noting a significant external factor that has boosted the Polish economy in recent years, namely, the absorption of around one million Ukrainian refugees since the beginning of the Russian aggression on Ukraine. In 2023, estimates suggested that Ukrainian refugees contributed between 0.7 and 1.1 percent to GDP in Poland.

Figure 1. Real GDP per capita in selected countries

Source: World Bank, GDP per capita, measured in purchasing power parity (PPP), constant 2021 international dollars.

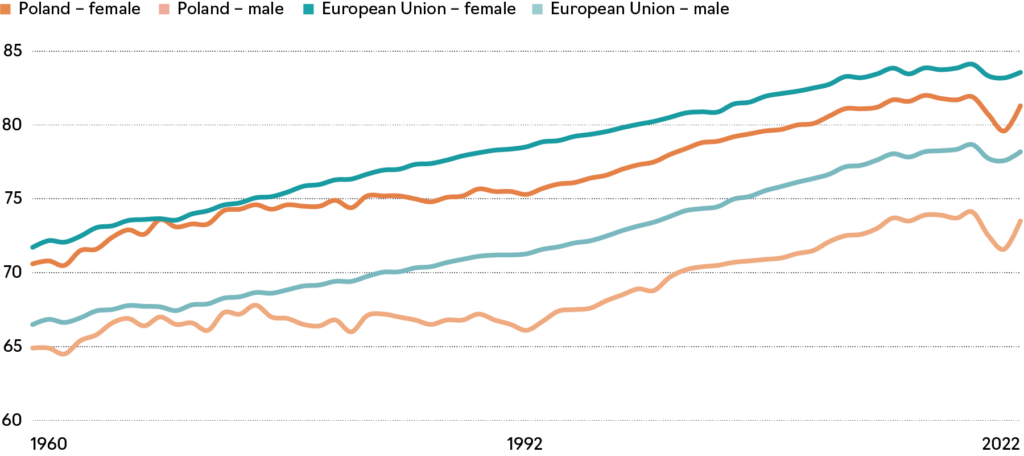

When analyzing the health component, it is evident that persistent challenges remain. Poland’s life expectancy continues to lag behind EU averages, particularly among men, who face a gap of over four years. Lifestyle factors such as high rates of tobacco and alcohol consumption account for much of this disparity. While smoking rates in Poland have declined in parallel with the EU, alcohol consumption has stagnated since 2007, posing an ongoing public health concern. Alcohol consumption is more than three times higher among men. Similarly, 28 percent of Polish men smoke tobacco, compared with only 20 percent of women.

Figure 2. Life expectancy by gender, EU vs Poland, 1990-2019

Source: World Bank.

The socialist economic system proved to be detrimental not only to consumers but also to the environment. The shift toward market-oriented policies in Poland significantly reduced the volume of emissions required to generate additional income per capita. However, the transition to an environmentally sustainable economy is not yet complete, as coal continues to play an important role in industry and energy generation. EU regulations in this area are expected to drive further change and the adoption of environmentally sustainable policies, though the pace of the reform will be a critical factor. While there is a risk that some of these regulations may be overly severe or implemented too quickly, the general direction of these measures is undeniably positive.

Turning to the minorities component, it seems clear that the marked decline in this component beginning in 2015 correlates with the rise to power of the PiS government. A detailed analysis of the underlying data confirm this connection. The sharp drop primarily reflects increased discrimination in access to public sector employment and business opportunities based on political The Path Forward affiliation. This decline illustrates the previously mentioned politicization of public institutions, including the prosecution office and public media, among other agencies that should have remained neutral and independent.

The path forward

Following the turbulent tenure of the previous government, support for democracy and the rule of law has strengthened in Poland. Consequently, there is little reason for concern, in my opinion, about the stability of these institutions in the near future. Instead, the more pressing issue lies in sustaining economic growth. Although Poland has significantly narrowed the income gap with the EU, including Germany, disparities remain, and the country faces several unresolved challenges requiring a new wave of reforms.

One persistent issue is the incomplete privatization process initiated in the 1990s. The public sector’s share in the economy remains high—one of the largest in Europe. To ensure sustained growth, Poland must pursue privatization and enhance competition in sectors like energy and oil processing. Unfortunately, no major political party has presented a comprehensive strategy for addressing this issue. Nonetheless, a carefully planned privatization initiative is essential for medium- and long-term economic growth.

Another major challenge is excessive fiscal spending, largely driven by social welfare programs. What is more, this spending is not effectively targeted, as it does not primarily benefit the poorest households. The tax and transfer system has a minimal impact on reducing income inequality. For instance, the “Family 500+” program, introduced by PiS and later expanded by the current government, provides universal child allowances irrespective of income and number of children in a given household. Such unselective transfers are more characteristic of populist policies than measures aimed at addressing inequality.

Finally, Poland shares demographic challenges with other developed nations, particularly the rapid aging of its population. Without substantial reforms, economic growth is likely to slow further, and fiscal pressures will intensify. Polish civil society has shown remarkable resilience in defending democratic institutions during recent crises. With these threats now neutralized, it is crucial for citizens to channel this energy to pressure the current government to implement essential reforms. These efforts will be vital to ensuring continued prosperity over the coming decade.

Leszek Balcerowicz is an economist and professor of economics at the Warsaw School of Economics. He served as deputy prime minister and minister of finance in the first non-communist government in Poland after 1989 (1989–91), and again between 1997 and 2000. He was president of the National Bank of Poland from 2001–07. A member of the Washington-based international advisory body Group of Thirty, he is founder and chairman of the Civil Development Forum, a Warsaw-based think tank.

The author is grateful to Bartłomiej Jabrzyk for assistance in the preparation of this paper.

statement on intellectual independence

“The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.”

Read the previous edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the data

About the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: Photo by Jacek Dylag on Unsplash

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media