Regaining trust in government

Table of contents

In his treatise The Road to Serfdom Friedrich Hayek argues that the abandonment of classical liberalism leads to a loss of freedom, the creation of an oppressive society, and in some cases the tyranny of a dictator. Several contemporary political leaders fit with Hayek’s foreboding picture, among them Vladimir Putin of Russia and Xi Jinping of China. In times of crisis, as during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, societies naturally demand new protections from their governments. These protections enhance security at the expense of freedom. The history of previous crises—be they economic, social, or due to wars and natural disasters—teaches us that such limits to freedom tend to remain in place long after the original purpose of regulation or state intervention has abated, and that this sometimes leads to the path Hayek predicted.

The world has experienced a sequence of significant crises in the past dozen years—the Great Recession in 2009–12, the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the COVID-19 pandemic, and most recently the war in Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas war—and governments have substantially increased their reach in economic and social life during these years. This expansion of the role of government challenges traditional liberal views on the foundations of freedom, and necessitates a new look at basic questions.

In designing policies to increase prosperity, one must also acknowledge challenges to standard economic theory, which predicts that, as societies become richer, more educated, and economically more developed, they should also experience a particular path of political institutional developments—that is, they become more democratic, increase respect for civil and human rights, and develop several other societal features we commonly associate with Western democracies. China is the most obvious challenge to this theory, but there are others, even in relatively prosperous European societies like Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, as well as Latin American countries like Venezuela.

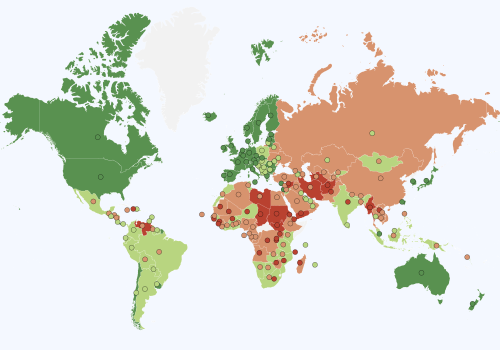

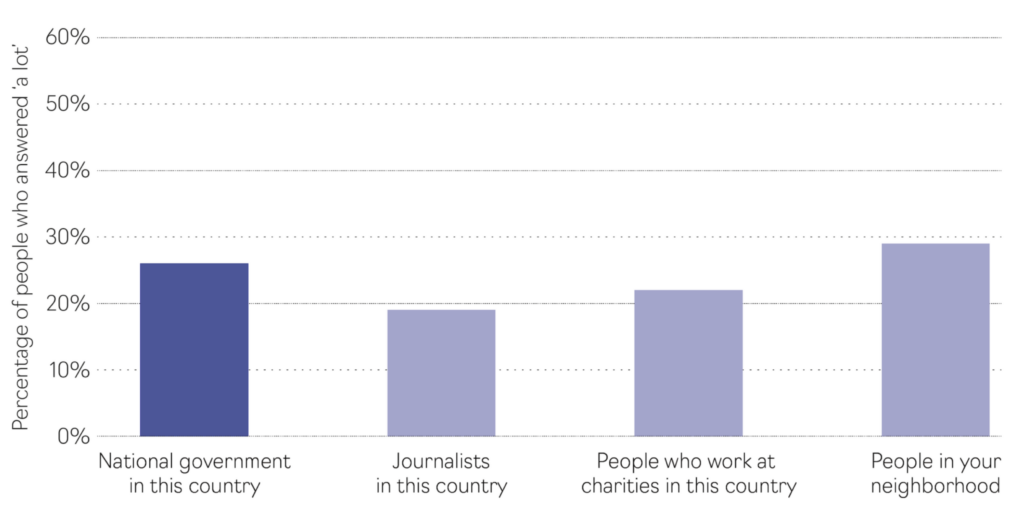

There is another worrying issue, too. The effectiveness of public institutions depends on the trust that citizens and businesses bestow upon them. However, in the last two decades trust in government has continuously fallen around the world, including in the advanced economies (Figure 1). Civic engagement helps people extend their trust from their familiar circle to include public institutions as well. While there is a long history of civic engagement at the local level in many developing economies, disruptions due to decolonization and war have made it difficult to replicate Europe’s results in participatory democracy to these economies.

Figure 1. Trust levels, global results (2020)

Note: Percentage of people who answered ‘a lot’ to the question: “How much do you trust each of the following?

Do you trust them a lot, some, not much, or not at all?”

The concern that comes out most often in country studies is over personal security. This concern comes through in countries at war like Ukraine or parts of Africa; in countries with high levels of gang violence, as in Brazil or several Central American nations; and in countries where political polarization brings about crimes and discrimination against minority groups, as in China or India. This dichotomy—between declining trust in government while requiring more government to ensure security—is the principal trade-off that has evolved in recent times. New technologies are increasingly used by governments to analyze individuals’ behavior, in the name of enhancing security. Such analyses disrupt the standard concept of personal privacy and can easily become tools in an oppressive society. Examples in China and the Middle East suggest that social protest or dissent, even as benign as views expressed on social media, is identified through the use of spying technologies, and is quickly stifled.

The importance of the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center is in identifying policies that build trust in government institutions while protecting personal freedom. Such policies are couched in political, economic, and legal reform. The task for governments is to disseminate the reasons for these policies being implemented and their likely impact on prosperity. This analysis helps policymakers and influencers in developing countries, as well as other organizations and individuals who are trying to expand freedoms through incremental or fundamental change towards prosperity.

This volume brings together the insights of some of the world’s leading economists and diplomats into how countries and regions pursue steps towards prosperity. Often these steps to prosperity ignore the role of freedom, but there is always an implicit association or algorithm connecting policies to freedoms—or the abandonment of those freedoms—and prosperity. This is precisely the goal of the Atlantic Council’s project: to document this algorithm and derive the success stories associated with it. In doing so, we hope to identify the roads politicians travel to attain prosperity.

This chapter is organized as follows: First, we summarize the views of eminent economic scholars and foreign policy experts on what the future may hold for some large countries and regions. We have chosen case studies where we see interesting dynamics that may affect global prosperity—be it because those countries and regions are large and home to significant portions of the world’s population, or because their policies affect neighboring countries and regions. Second, we describe four worrying trends related to raising prosperity. Finally, we suggest some directions for future work to convince politicians and influencers of the link between freedom and prosperity.

Likely issues in the next decade

In this section we summarize the views of contributors to this volume on the likely direction of change towards freedom and prosperity in the next decade. We list countries and regions alphabetically, though their respective dynamics may be quite diverse. These countries and regions are chosen for analysis as they represent a large share of the world’s population. Their policies often affect the global consensus on significant prosperity-related debates too.

Africa

Economic liberalization across Africa has borne fruit in the past decade and further financial and trade integration with the rest of the world would have continued benefits, argues William Easterly. The big challenge is to strengthen the process of democratization and institution building. The necessary reforms in these areas are harder to accomplish. The recent wave of military coups in countries like Burkina Faso, Gabon, Niger, Mali, and Sudan is a worrying sign, and there is ongoing conflict associated with Islamic movements in some areas, for example, in Nigeria. The resolution of conflict and the maintenance of peace and security are crucial necessary conditions for further development in Sub-Saharan Africa.

It is unlikely that international institutions and foreign countries will provide as much support for African development as in the past. Things tend to go in cycles: there was a lot of support and attention for African development in the 1990s and 2000s, though foreign support was not all that successful in achieving economic growth; foreign aid did receive some of the credit for the progress on health and education, however. Since then, the focus has shifted to other parts of the world, like Ukraine and Eastern Europe, and the situation in Israel and Gaza is also drawing attention towards the Middle East.

In terms of Sub-Saharan African development, the Belt and Road Initiative, led by China, is having similarly disappointing results to the significant funding received from Western nations during the 1980–2010 period. The same problems of debt repayment and default are likely to be repeated with China’s investments. At the end of the day, for foreign investment and aid to successfully affect Africa’s economic development, it has to be directed to some productive uses. And this is not usually the case as this kind of financing is heavily politicized.

Finally, within-region trade is unusually low for neighboring countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. But increasing it is certainly not an easy task, as the several unsuccessful attempts to promote free trade areas or common currencies in the region in the last couple of decades attest. This failure may be due to Africa’s burden of having so many small states, creating divisiveness. This generates great difficulties in reaching agreements because there is a multitude of strong political interests that do not trust each other.

Argentina

The economic situation has materially worsened in recent times. Weekly inflation at the end of November 2023 is running at 3.1 percent, which implies an annualized rate of 230 percent. That is, Argentina is experiencing in a week the level of inflation that normal countries see in a year. Related to this, Argentina’s poverty rate in 2023 was close to 42 percent of the population.

It is understandable that the Argentinian people are frustrated, and are looking for someone new, outside of the traditional parties, argues Guido Sandleris. It seems like a revival of the mantra “¡Que se vayan todos!” (They all must go!) of 2001. And the new man that Argentinians have chosen as president is Javier Milei, an outsider to the traditional political system of Argentina. His ascent makes the prospects for the next few years highly uncertain.

Like many other politicians, Milei has identified real problems in the country (inflation, high and inefficient public spending, political capture, corruption, and so on), and has proposed a series of easy-sounding solutions. And the Argentinian people have voted for this project. Nonetheless, it is obvious that solutions will be anything but easy, and Milei has already walked back on some of his positions. Dollarization is the obvious example, as there are just not enough dollars in the Argentinian Central Bank to dollarize the economy, at least in the short run. Furthermore, Milei’s position in the national congress is weak, so to enact legislation, he needs to build consensus with the traditional parties around more moderate proposals. Cutting public spending is always unpopular, so it is highly uncertain whether President Milei can get enough parliamentary support on that front to push forward proposals.

The touchstone of President Milei’s administration is going to be the macroeconomic situation, which is extremely delicate. Argentina is on the verge of hyperinflation, and a situation in which the economy basically stops. It is likely that some of Milei’s reforms to tackle inflation in the medium term, like the correction in utility prices and the exchange rate, will actually generate a rise in prices in the short run. He will only be successful if he can offer a fiscal anchor to the economy, and make credible the commitment of the Central Bank to stop printing money to finance the Treasury; this is not an easy task.

Brazil

The private sector in Brazil faces a huge number of hurdles, according to José Scheinkman. Taxes are high and inefficient. Firms are more worried about paying less tax than producing in a more efficient way, because it does not pay. Regulations in Brazil are especially inefficient and there are important difficulties regarding long-term financing, related to the legal risks and fiscal deficits in the country. The labor market is rigid and President Lula announced plans to impose new labor regulations in 2024. If adopted, such regulation dims the overall economic prospects for Brazil.

Security is a fundamental challenge for Brazil. In particular, this concern refers to the opening of a new route for drug trafficking—from Latin American producers in Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia into Europe—through Brazil. As a result of this illegal activity, some Brazilian gangs are becoming powerful and fight with each other for control of the routes, increasing crime. For the first time in decades, paramilitary groups are appearing. These groups are more organized than the gangs and they have started to harass legal businesses. Paramilitary groups also control part of the logistics and construction sectors.

Some policies ease the burden on legal businesses, like the tax reform that the government is preparing for 2024. It is hoped that this reform will simplify the tax code and eliminate various exceptions and loopholes that benefit businesses with links to politicians. Brazil has the cleanest energy mix of any large emerging economy, thanks to its abundant water and solar resources. The government is dealing effectively with the illegal deforestation going on in the Amazon. This can make Brazil the biggest exporter of goods that have a positive climate footprint. Finally, the largest corruption scandal in Brazil’s history—surrounding the Brazilian multinational Odebrecht, which admitted guilt in a cash-for-contracts corruption scandal in twelve countries—has resulted in more trust in prosecutorial authorities and cleaner public procurement.

Chile

Chile has two big challenges in the coming decade, one economic and one political, writes Andrés Velasco. The big economic challenge is that Chile is not a fast-growing economy anymore. That is a big structural break. Productivity growth, which was very fast late in the twentieth and early twenty-first century, has gone down. Investment rates have not dropped, but nor have they increased. Chile was a country with a large diversification of exports, and that diversification process has come to a halt. When it comes to prosperity, the big question is: Why was the fast-growth period in Chile so short-lived?

Economic theory predicts that, as a country becomes richer, its growth slows due to a convergence process. But we would have expected fast growth in Chile until the country’s standards of living had reached the level of South Korea, for example. Instead, fast growth seems to have stopped with living standards only at the level of Greece.

Regarding inequality, the country has slowly improved in the last few decades, despite the really poor initial level of this indicator. But there is high uncertainty regarding the potential medium-term effects of the events of recent years. In particular, the very lengthy school closures that Chile imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic seem to be exacerbating inequality of opportunity. Most Latin American countries closed their schools for longer than European countries, but even within the region, Chile’s restrictions lasted longer than most. And this decision worsened inequality. If you had a good internet connection and your school could teach online, then the loss of learning was minimal. But if all you had was one bad internet connection via somebody’s cell phone, and the school was not well equipped to teach online, then nearly two years of school closure is clearly detrimental for the development of human capital and for equality in the future.

The big political challenges have to do with the sociopolitical climate. Chile was a consensual country in the years between the return of democracy in 1990 and around 2010. Since then, politics has become polarized. Power has become a lot more fragmented. Chile went from having seven parties in Congress to twenty-two. If you look at indices of satisfaction with the performance of democracy, or indices of trust in government, political parties, the judiciary, the police, the media, business lobbies, unions, and so on. they have all deteriorated. It seems that Chileans do not trust anyone anymore. That is a worldwide trend, but in Chile it might be a little more pronounced. The big question is: How do you restore politics?

Chile’s answer has been to try to rewrite the social contract: the Constitution. Politicians have tried twice already and failed, and the third time is not looking good. President Bachelet drafted a new constitution in her second term, but she ran out of time to get it approved. A constitutional convention was chosen in 2021, which wrote a terrible text that was rejected by 62 percent of voters a little over a year ago, and a new convention was elected. And Andrés Velasco’s prediction was correct. In December 2023, Chileans rejected again the proposed changes to the Constitution.

China

China is missing the chance to create a more dynamic society—the “Chinese dream.” Meanwhile, other East Asian countries have improved their freedoms considerably, despite slower income growth. They seem to do more with fewer resources to enhance their societies’ prosperity, argues Johanna Kao.

The primary question the Chinese government needs to address in the next decade is whether the policy choices being made are sustainable. The economic turmoil during the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced public trust in the effectiveness of the Chinese growth model. The most striking aspect of the evidence is the government’s commitment to an inherently unequal form of governance, particularly when it comes to individual and subgroup rights. While China is often described as having a collectivist approach, where the well-being of the collective outweighs individual freedoms, the data suggest a more selective approach to collectivism. In Xi Jinping’s model of government, certain groups are favored at the expense of others.

This type of inequality is not a new phenomenon in China. Historically, there have always been winners and losers, with the party elite and affiliated businesses reaping the rewards of extraordinary economic growth while the general population experienced more modest improvements. Yet, in the past, the wealth gap in China was often characterized as urban versus rural. In the past decade there has been a shift towards absolute, rather than relative, inequality. There are clear losers in this system: individuals and groups that have experienced a significant loss of freedoms.

As we look into the next decade, equality seems likely to deteriorate, with the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) representation of the collective shrinking. These dynamics put pressure on individuals to conform to a more limited definition of acceptability or face forced assimilation. The trend is exemplified in regions like Xinjiang, where the Uyghurs are subject to extreme reeducation efforts. The rapid expansion of surveillance technology in the name of security, and its use in determining whether people meet the imposed standard of a “good citizen,” are likely to make things worse.

East Asia and the Pacific

The region unveils a narrative deeply intertwined with historical events and ongoing geopolitical shifts writes Amb. (ret.) Kelley E. Currie. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1988–89, a wave of democratization swept through East Asia and the Pacific. However, progress stagnated thereafter, with democratization efforts in countries like Indonesia not significantly altering the overall political landscape at a regional level.

The period from 2012 onward witnessed visible improvements in political and economic freedom, primarily attributed to Myanmar’s quasi-democratic transition and increased political dynamism in Malaysia. However, China’s economic growth, accompanied by limited political liberalization, took a downturn after 2013 with Xi Jinping’s ascension to power, exerting downward pressure on freedom across the region. This pressure is exacerbated by China’s internal policy shifts and its external influence on neighboring countries’ democratic and economic development.

Notably, the region saw significant progress in women’s economic freedom, driven by efforts to enhance female workforce involvement and dismantle regulatory barriers. This progress, spearheaded by initiatives like the Women’s Global Development and Prosperity Initiative, has played a pivotal role in driving economic growth in the region.

Despite economic resilience, challenges persist in areas such as inequality, minority rights, weak political institutions, corruption, and regression in the rule of law. The region’s youth population increasingly demands responsive political systems and sustainable growth, highlighting the need for environmental preservation and pragmatic solutions.

In navigating the complex landscape of freedom and prosperity, regional cooperation and support from global allies are paramount. Strengthening institutions and building political and economic resilience remain imperative, ensuring stability and prosperity amidst evolving geopolitical dynamics and internal challenges.

Egypt

Egypt will have to navigate difficult macroeconomic challenges in the next few years. The country is heavily indebted, and that may tilt the scales of an already worrisome sociopolitical situation, says Rabah Arezki. In the December 2023 elections, President al-Sisi will be reelected and there will be no appetite for political reforms. While his reelection should give him a mandate for reform, it is unlikely that al-Sisi will make any changes that affect crony or military interests. Instead, al-Sisi might have to resort to further devaluation of the currency, which would ignite further inflation and hurt vulnerable households. What is more, this would create a fatal currency mismatch when it comes to Egypt’s external debt denominated in foreign currency.

Al-Sisi will have to find external sources of financing outside of capital markets, given the prohibitive spread on external borrowing. Financial aid from Gulf countries, which typically provided a lifeline, is no longer forthcoming. Gulf countries are looking to invest in strategic assets but also want to see reforms before doing more to support the country. Gulf partners are counting on the International Monetary Fund to push for more market-oriented reforms.

While political reforms are unlikely given the current circumstances, deep economic reforms also seem improbable. Indeed, the militarization of politics and of the economy is so entrenched as to make reform of either one unlikely. This stalled situation will likely continue to limit Egypt’s potential. It is imperative that the country re-embarks on a balanced economic and political transition, to avoid the youth becoming frustrated and creating domestic instability.

The geopolitical situation is also tense. The renewed escalation of violence between Israel and Gaza is spilling over into Egypt. That could destabilize the country and in turn spill over to the whole Middle East and North Africa region.

The European Union

The next decade of European Union (EU) freedom and prosperity dynamics will be marked by the war in Ukraine, writes Simeon Djankov. The EU has committed enormous financial resources to supporting Ukraine’s fight against the aggressor. It has also imposed sectoral and economy-wide sanctions on Russia. These sanctions have negative implications for some industries in Europe, which have traditionally relied on resources from Russia.

The main influence of Russia’s war in Ukraine is the rethinking of the Green Deal that the European Commission has championed for the past decade. Given Russia’s threats to Europe’s energy security, a decision was taken in 2022 to reduce the dependence on Russian energy products. With only two countries—Bulgaria and Hungary—receiving postponement of these measures to 2024, Europe has quickly weaned itself off Russian oil and gas. This change, however, has come at an environmental cost: a number of countries have increased the use of coal and other high-polluting sources of energy.

The past decade has shown evidence that Europe cannot multitask—perhaps the hallmark of gradual consensus building among twenty-seven member states—appearing to focus on one item at a time. When it comes to increasing freedoms, the clear task at hand is helping Ukraine win the war.

Europe’s prosperity agenda is fourfold: First, there are wide disparities across regions within Europe. This disparity is seen within countries, for example southern versus northern Italy, and across countries, for example Scandinavia versus southeastern Europe. A significant portion of the EU budget is directed to reducing these disparities, through investments in infrastructure, agriculture, and regional economic development. Such financial aid needs to be coupled with policies that increase economic freedom at the regional level. For example, decentralization of some tax policies, combined with explicit subsidy schemes, will keep more resources in underdeveloped regions and thus attract businesses and individuals who would otherwise look for opportunities in more advanced parts of the EU.

Second, increased prosperity in the EU comes from completing the internal markets for energy and financial services. These topics were discussed even before the 2014 annexation of Crimea, which ushered in a series of crisis years for the EU. 2024 is a good moment to go back to the original design and create a single energy market in Europe, as well as a single financial market, with a single set of regulators. Much has been written and discussed about how to achieve these goals; now is the time to act.

Third, migration has been at the forefront of European politics for the past decade. It promises to remain an issue in the decade to come. On the one hand, Europe’s demographics are such that the labor market benefits from human capital coming into European countries and putting their labor and talents to productive use. On the other hand, social tensions have risen in the countries that have received large numbers of migrants. Even in countries with relatively few migrants, the specter of competition for social services and jobs has boosted the fortunes of nationalist parties that have promised to erect barriers to further migration. This issue inflames public opinion in Europe to a degree that no other issue does.

Finally, prosperity in Europe emanates from open markets. While the European market itself is large, many innovations and technologies come from either the American or Asian markets. The two other superpowers—the United States and China—have been on a collision course in asserting their economic dominance, leaving Europe to choose how to align in the global picture. So far this path has meandered, with calls for protecting Europe’s own market. Such an isolationist approach is counterproductive. Europe has to remain as open as possible, assimilating leading innovations and creating the space to implement these new ideas into better production processes and products.

India

The evolution of political freedom in India is worrisome, posits Pratap Bhanu Mehta. There is a high probability that political freedoms might decline even more in the next decade. The way in which the Modi government has empowered hate speech against minorities and co-opted the judiciary is concerning.

It is the first time since 1975 that we must ask the question: Will there be a smooth transition of power? If it looks like this government is struggling and could lose the election, will it accept that transition of power as smoothly as India is used to? There is a catch-22: if this government wins, the majoritarian consolidation will be a continued threat to political freedom. But if it looks like it could lose, then the chances of it resorting to extra-legal means to either hold on to power or making sure that the successive government is not able to function have risen considerably. There is already evidence of this behavior in state elections which the ruling party has been losing. In many of them, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is deploying the central government’s power to break up the state governments that have been elected.

On the prosperity front, there are reasons to be optimistic. Large sectors of Indian capital and foreign investors have learned to live with limits to political freedom. If they can make money, they will continue operating in India. An open question is whether improving prosperity will be enough to overcome the structural problem of the middle 40 percent of the population in terms of income distribution. This conundrum makes the politicians’ jobs harder. The opposition is struggling to align deep economic discontent with voting in elections.

Kenya

One of the critical issues that Kenya faces in the next decade is how to keep improving productivity, says Robert Mudida. An obvious area for improvement is manufacturing and its share in gross domestic product (GDP), which in 2023 was slightly below 10 percent. Kenya should double that share. There is a big opportunity in Africa with the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area. It would create tremendous opportunities for countries like Kenya, which have some manufacturing bases. Bigger markets can generate productivity improvements.

An important challenge for Kenya relates to the large share of informal employment. Moving some of these workers and firms towards formalization will ensure that economic opportunity and development are more stable. Higher levels of formal employment and production generate larger and more stable sources of government revenue. This will buttress the already firm fiscal consolidation path that Kenya has followed in recent years.

The current account deficit has also been declining in the last decade, partly because of reduced imports, but also due to stronger and more competitive exports. This is a very promising path for Kenya, which needs to take advantage not only of regional value chains, but also global value chains in areas like tourism. It helps that Kenya is perceived as peaceful and secure in comparison with some of its neighbors.

Mexico

Mexico continues to maintain key technical and autonomous institutions, which have made it resilient to affronts to political, legal, and economic freedoms, writes Vanessa Rubio-Márquez. These institutions have helped sustain a basic level of prosperity. However, the negative developments in some of the indicators serve as early warning signs for the country. Some point to the uneven path forward if the country wants to advance towards the next stage in democratic consolidation and progress in well-being standards. These can be summarized in three clear pillars: strong institutions, high sustained growth, and well-articulated redistribution policies.

Mexico remains a bastion of free trade in Latin America and is in a strategic position, being the United States’ largest trading partner. Amid US-China decoupling, gains from nearshoring could be significant. This has mostly materialized into expectations, however, and only very recently into actual investment commitments. Expectations cannot materialize into more significant commitments if the institutional framework continues to weaken. In many ways, Mexico has de jure maintained the institutions and legal framework to support political, economic, and legal freedoms—including an independent central bank, an autonomous Supreme Court of Justice, and an independent National Electoral Institute. But a de facto deterioration is clearly occurring in the form of political appointees to key autonomous institutions, budget and staff cuts, and a centralization of power under the president, all of which are impacting growth and prosperity.

In this sense, pendular politics remains a significant risk to institutions and continuity of sound evidence-based policy making. The country heads to the polls in June 2024 and the signs of polarization have not wavered. While disagreement and debate are essential components of a healthy democracy, the current discourse in the country is all but constructive, and radical shifts in policy put at risk the possibility of high sustained growth and well-being improvements more broadly.

High sustained growth and strong institutions are therefore prerequisites before considering redistribution policies; if they are not in place, the country is likely to continue on a path of uneven progress. After unlocking high sustained growth, the country can turn to enhancing institutional capacity to deliver and redistribute gains—and the country has a good track record of institutional capacity for infrastructure and redistribution policies. The risk here then is that the country continues on a path of discontinuity, with every incoming administration embarking on pet infrastructure projects and unfocused social policy.

The Middle East and North Africa

Over the next decade, countries in the Middle East will have to grapple with economic and political transitions in a world in mutation. To achieve freedom and prosperity, countries in the region will have to face risks linked to geopolitics, climate change, and the transformation of energy markets, as well as social polarization, argues Rabah Arezki.

The region is at a tipping point when it comes to conflict escalation. Indeed, the alarming intensity and casualties resulting from the conflict between Israel and Hamas risk engulfing the whole region. This new phase of escalation of violence brings not only tragic loss of lives but also physical destruction, fear, and uncertainty. This renewed violence will have far-reaching economic and social consequences. What is more, the Palestinian issue is an important fault line between the Global North and the Global South, one that could have global repercussions and pull the region further apart.

The region is most exposed to the existential threat posed by climate change. Climate change is simply making this region unlivable at a faster rate than any other. Specifically, a water crisis is looming in the Middle East, heightening domestic tensions and interstate conflicts. Temperatures have reached record highs. And the crisis is made worse by the inadequate governance of the water and other utilities sectors, which has exacerbated the frustration of the citizenry over poor public services.

The region also needs to transition away from fossil fuels. Oil prices have been persistently high and provided some respite to the many oil-exporting countries in the region. Yet, as the world moves away from fossil fuels, the vast reserves of oil and natural gas with which the Middle East is endowed will become stranded—and so will the capital investment in the sector. Several Middle Eastern countries have embarked on ambitious diversification programs to move away from oil, though as yet there is little to show for these efforts. Saudi Arabia’s ambitious economic and social transformation agenda, if successful, could be a game-changer for the region and offer a model for other countries to emulate.

A credible economic and social transformation agenda is long overdue to meet the aspirations of an educated youth and to absorb the millions of young women into the labor market. The abortive political transitions have, however, polarized societies in the region. Two sides stand in opposition, with the people on streets who continue to protest on one side, and the political elites and crony capitalists on the other.

Pakistan

The defining question for Pakistan’s near-term future will be around political stability, comments Ali Cheema. Even though the country has been involved in a transition towards democracy since 2013, it has been full of political instability. The 2013 election results were not accepted by the opposition, leading to protests in the streets, and the same happened after the 2018 election. This political instability is concomitant with the deterioration of political freedom in the country, making Pakistan a much more repressive society. And political tensions generate policy instability, with politicians’ and bureaucrats’ incentives to reform and create state capacity being significantly diminished. The ensuing uncertainty around the regulatory framework represents a major constraint on Pakistan’s development. Today we observe a breakdown of the consensus over the electoral process, which sometimes means that transitions of power do not take place within the timeframe mandated in the Constitution.

Russia

The prospects for Russia are determined by the evolution of the war in Ukraine. Putin’s regime entered a declining stage even before the beginning of the war, which is typical of authoritarian and personalistic regimes, argues Konstantin Sonin. It is the last stage, after a period of stagnation, where every effort of the regime is devoted to maintaining power. Even before 2020, political repression was very substantial. There were tens of thousands of people leaving the country every year because they feared arrest if they said something “wrong” on social media, for example.

For Russia, there is no easy way out of the war, nor from Putin’s authoritarian rule. Change in any personalistic regime is always dramatic and turbulent, and even if a lot of the same people still hold power, it always implies substantial changes. It was the same after the death of Stalin.

There is an upside to dramatic change, because when Putin is gone, the new leadership will be able to do some things that will represent an immediate improvement for Russia. For example, any new leadership can withdraw the Russian troops from the occupied territories. And talks about lifting economic sanctions and reopening trade will immediately follow. Some companies that left Russia will quickly return, but this return may not generate a huge economic boom, as the loss of growth potential due to the war is substantial. Nonetheless, it will represent an immediate improvement over the status quo. But in the near term, as long as the war continues, Russia will suffer further decreases in every dimension of prosperity.

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom’s transformation agenda is a form of state-led capitalism. The political structure remains unchanged while the leadership focuses on reforming the economy, writes Rabah Arezki. There is no tolerance for any dissent, including on social media, where users are monitored closely using surveillance technology. The notion that economic transformation can happen independently of political transformation is certainly taking a page out of China’s book. This approach may badly backfire.

Despite the absence of political freedom, Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) has managed to rally the population behind him. Unlike many other leaders in the Middle Eastern region, MBS is popular. In fact, he enjoys a level of popularity that was last experienced by leaders immediately following independence. Such cohesiveness could create momentum for the Kingdom to enact further bold reforms. Yet the escalation of violence between Israel and Hamas risks derailing the transformation agenda, as a result of the heightened uncertainty. While MBS has thus far navigated the new geopolitical environment, it is unclear whether Saudi Arabia’s situation in the region will remain tenable.

Most if not all investments pertaining to the transformation agenda are financed with public money. That public money will eventually run out, as the world economy moves decisively away from fossil fuels. A true test of the sustainability of the economic transformation agenda is whether reforms will attract (domestic and foreign) private investments instead of public investments. All in all, the Kingdom’s unbalanced transformation, focused on the economic (and social) dimensions, may prove short-lived as more and more educated youth will demand more political freedom.

South Africa

In South Africa, the response to the COVID-19 pandemic brought about stringent health restrictions, arguably among the strictest worldwide, including severe lockdowns and limitations on movement. The measures, intended to curb the virus’s spread, led to a notable decline in civil liberties protection, compounded by proposed legislation aiming to curtail civil society’s activities, argues Greg Mills. This decline in legal freedom has been accentuated since 2008, marked by efforts to consolidate power within the criminal justice system, raising concerns about bureaucracy quality and corruption.

South Africa’s recent development trajectory has seen a decline in prosperity, particularly evident in the health sector. The initial post-apartheid years were marked by positive economic growth fueled by redistributive policies, but subsequent years witnessed stagnation, exacerbated by political changes and the global financial crisis. The health indicator’s dramatic dynamics reflect shifts in government approaches to healthcare, with notable impacts on life expectancy and COVID-19 response effectiveness.

South Africa grapples with significant inequality, driven by a dysfunctional labor market and expansionary policies that failed to address unemployment. While initiatives aimed to expand the middle class, they widened the gap between those with secure employment and those without. The country’s environmental progress remains sluggish, attributed to reliance on fossil fuels and slow transition to renewable energy sources. Despite strides in education enrollment, concerns persist regarding declining educational quality, evidenced by global benchmarking tests.

Looking ahead, South Africa’s political landscape will shape its future trajectory, with the 2024 election holding crucial significance. A shift towards a coalition system could foster greater accountability but also bring political instability. Addressing fiscal challenges and reevaluating global alignments, particularly with BRICS nations, will be imperative for South Africa’s journey towards sustained freedom and prosperity.

United States of America

The United States formal political and civil institutions remain relatively stable, offering a semblance of continuity amidst escalating public discord, write Edward Glaeser. However, the domain of public discourse has undergone a decline, veering sharply from the norms expected within a stable democracy. This is characterized by heightened polarization and a surge in confrontational rhetoric, exacerbated by erosions in civil liberties and legislative constraints, particularly notable since the year 2016.

On the economic front, the United States is holding up well overall, but it’s not without its flaws. Issues like inequality and a growing national debt pose potential challenges for future prosperity. Notably, there are noticeable shifts in how free trade and property rights are perceived, indicating changing attitudes and uncertainties around regulations. However, despite some minor adjustments at the state level, there hasn’t been a significant push for widespread reforms.

On the prosperity front, the United States remains relatively stable, thanks to its strong economic foundation. However, problems persist in areas such as healthcare and entrenched inequalities, exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. While there have been some improvements in environmental and educational sectors, significant hurdles remain, necessitating concerted efforts towards reform and fostering more constructive political discussions.

Looking forward, addressing the mounting national debt and navigating the challenges posed by political polarization are critical priorities. Reforms aimed at simplifying regulations for small businesses, improving procurement processes, and enhancing overall government efficiency are essential for sustaining economic growth. Yet, fostering civil discourse presents a formidable challenge, given the deep divides and identity politics shaping contemporary debates. This underscores the complexity of forging a cohesive national vision amidst evolving challenges.

Ukraine

The future of Ukraine will be shaped by its accession to the EU and NATO, writes Yuriy Gorodnichenko. Joining the EU implies convergence in terms of the legal structures, economic conditions, and environmental and health standards. The experience of Poland and other former communist countries suggests that Ukraine will see radical improvements after accession—in labor productivity, market access, infrastructure, and other key metrics of economic progress. Joining NATO will be critical for addressing security concerns. NATO can guarantee peace and thus make Ukraine an investable country and bring refugees back to Ukraine.

There is a widespread perception that the Ukrainian judicial system does not adequately protect private property or the individual rights of citizens, and that it does not act as an effective check on executive power. This is a fundamental challenge that needs to be addressed in the next decade if the country is to become a success story.

The war will leave many scars on the country. These will be not only the destroyed factories and homes (although rebuilding these could allow the country to modernize its infrastructure and productive capacity), but also the huge swaths of lands that will need to be de-mined, the many millions of displaced Ukrainians who will return, and the many (likely over a million) war veterans who will need reintegration into civilian lives, including hundreds of thousands who will need medical rehabilitation.

Furthermore, there is a generation of children who will not have received a proper education, during COVID-19 and then the war. The losses of human capital are enormous and hard to reverse. Estimates of Harmonized Learning Outcomes due to this length of school closure show a fall from 481 to about 420 points, well below the lowest-performing countries in Europe: Moldova and Armenia. The long-term effect could be substantial, with future earning losses of more than 20 percent a year per student.

Four worrying trends for prosperity

Privacy is the first worrying trend for prosperity. Some of the most prominent economists and foreign policy experts contributing to this book highlight the trade-off between strengthening security and increasing freedoms. The topic of security comes up in three-quarters of the country and regional studies: be it security from war and civil unrest or security of property and political freedoms. Enhanced technology tilts this trade-off heavily towards fewer individual freedoms, as more and more possibilities arise for individuals to be closely monitored in their daily routine. The rise of surveillance technology in curtailing freedom is seen in various locations, for example, China, Russia, and the Middle East.

Do technologies that reduce freedom nevertheless serve the common good? Big technology companies make precisely that claim: the more information they have, the better data analysis is possible to decipher consumer needs and increase prosperity. The same data can be used, and perhaps are used, to spy on individuals or groups deemed “of public interest.” The EU has taken recent steps to limit the use of facial recognition technology in public spaces. Various other countries are considering similar regulations.

The second worrying trend is the loss of human capital during the pandemic and the lasting effects that this loss has on productivity and equality of opportunity. In Ukraine, approximately two years of education was lost due to the pandemic, followed by Russia’s invasion. Estimates imply that these losses amount to about 20 percent of the future earnings of this generation of children. In Chile, one of the countries that imposed the strictest pandemic measures, the loss could be about 10 percent of long-term earnings. In several Middle Eastern countries, the losses are similar. More worrisome, the lack of access to online education among the poor meant that some children dropped out of school altogether, for example in Egypt.

The third worry is the changing goalposts on the transition to net zero. Prior to the war in Ukraine, the world had, with some effort, approved the Paris Agreement—a legally binding green deal. In this regard, the main impact of Russia’s war in Ukraine is the rethinking of the Green Deal in Europe. Given Russia’s threats to Europe’s energy security, a decision was taken in 2022 in Brussels to reduce the dependence on Russian energy products. This change, however, has come at an environmental cost: a number of countries have increased the use of coal and other high-polluting sources of energy. Other countries have also rolled back their commitments, for example, the United Kingdom.

The fourth worrying trend for prosperity is declining productivity growth. This comes in two flavors: demographic decline, implying fewer workers in China and Europe over the next decade; and rising social tensions, as we are already witnessing in Argentina, Chile, India, and the Middle East, for example, implying that young adults may not be joining the labor force as quickly as in previous decades. Stagnant productivity directly affects prosperity and is the focus of many government programs. Saudi Arabia’s 2050 program, for example, targets new high-value-added sectors as a response to the likely decline in natural resource sectors. So far, however, the investments in these new sectors are primarily public. To shift sufficient resources towards new industries, the private sector also has to believe that the returns will be there.

Open questions

Throughout the chapters in this volume there is a common underlying belief, supported by evidence, that a higher degree of freedom is consistent with a faster path to prosperity. There are some politicians who do not share this belief, and hence further work is needed to convince them.

Not a perfect fit

The first issue that arises in discussions of the link between freedom and prosperity is that the correlation is not perfect. The R2 statistic of the univariate regression implies that 63 percent of the variance in prosperity can be explained by differences in freedom across countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The correlation between freedom and prosperity in 2022

If we conclude that there exists a close relationship between freedom and prosperity, this raises a methodological question: namely, that we are pooling together countries from all continents, and thus disregarding significant differences among regions. However, a strong positive association between freedom and prosperity scores is also present within regions. The correlation coefficient is above 0.6 for all regions, except South and Central Asia (0.41), which is probably due to the small number of countries (twelve) in that region. So across all regions, we observe that countries with higher freedom scores also have higher levels of prosperity.

Perhaps prosperity explains freedom

In a nutshell, freedom and prosperity are closely associated, but is there a causal link? And in which direction does it run? Does freedom today lead to prosperity tomorrow, or is the demand for freedom a consequence of societies becoming more prosperous? To be sure, this is a question that has received extensive attention from economists and political scientists and is still a matter of heated debates.

One can start by noting that freedom in 1995, the start of the sample period, is positively correlated with prosperity in 2022, the end of the sample period. This association is statistically significant at the one percent level. The time lapse between the explanatory variable (freedom) and the dependent variable (prosperity) is sufficiently long to ensure that no feedback loop—from higher prosperity to increased freedom—is responsible for the result (Figure 3). When running the reverse regression (freedom in 2022 on prosperity in 1995), the R2 statistic is lower, at 0.553, which provides some support for the argument that the direction of causality runs from freedom to prosperity.

Figure 3. The causal relation of freedom level in 1995 and prosperity level in 2022

We look for outliers in the data to see whether some countries defy this long-term pattern. Yemen is such a country. In recent years, it has become a failed state and regional powers vie for a dominant position at the expense of the prosperity of the population. These dynamics are consistent with Yemen’s relative standing: more freedom and less prosperity relative to the sample trend line in Figure 3. In essence, past freedoms were insufficient to lead to prosperity in 2022—as the civil war (engulfing the country since 2014) undermined the country’s progress.

The case of Yemen demonstrates a general pattern: countries in civil war or countries involved in other recent conflicts tend to be below the trend line. Examples include Burkina Faso (2015–16 conflict), Chad (2005–10), Mali (2012–present), and South Sudan (2013–17).

At the other end of the spectrum, the United Arab Emirates stands out as having a high level of prosperity in 2022 and fewer freedoms at the start of the sample period. This seeming discrepancy can be explained by the able management of natural resources.

Time lags mask the relation

To be sure, changes in freedom do not immediately bring about changes in prosperity. The size and scale of the lag depend on various place-specific factors, and also factors related to the condition of the global economy. The relationship between changes in freedom and changes in prosperity can be disrupted by events such as civil conflict or war, a shift toward dictatorship, or closed economic policies. Over time, such shifts will become evident in prosperity measures. The remainder of the explanation lies in sudden shocks such as war and civil conflict, the rise of dictatorships, and the advent of global crises, be they economic, financial, or health related.

One can, for example, speculate that the increased levels of freedom in Taiwan have not yet resulted in a commensurate increase in prosperity due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which severely limited global trade and investment. Conversely, the limits to freedoms in Mali may yet reduce prosperity as the effects of the protracted civil war are only now manifesting themselves in reduced social and economic indicators.

Based on the data, one can also speculate that the imperfect relation between a change in freedom and change in prosperity is asymmetric. Losses in freedom result in swift losses in prosperity, as illustrated by Yemen, Venezuela, and Syria. In contrast, improvements in freedom take a longer time to result in improved prosperity. In other words, it takes a longer time to build than to destroy.

The latter finding is particularly relevant for politicians, as their time in office is usually limited and they would like to see results fast enough that they are reelected, or at least so that the ultimate increase in prosperity is attributed to their work. Alas, such attribution is sometimes not possible. This delay likely results in some “good” reforms not taking place.

Reversals of fortune

Should political freedom take too long to evolve, the gains from economic and legal reforms may be reversed. Russia in the 1990s and 2000s is a prime example of such a reversal. And China seems to have been following the same path in recent years: economic freedom and legal freedom have remained stable in our sample, but political freedom has declined by 26 percent since Xi Jinping took office in 2013. Prosperity had increased 17 percent from 1995 to 2013, but has since plateaued.

Reversals significantly affect the overall correlation between freedom and prosperity, as the pace of change in the two sets of indicators differ, and hence the relationship appears weakened or even lost. The use of longer-term time series would fix this disparity, another reason why the Atlantic Council is investing in the construction of these Indexes.

It’s something else

The final counterpoint to advancing policies that improve freedoms and, from there, have a positive effect on prosperity is the argument that freedom indicators proxy for some other social dynamic that underlies changes in prosperity. In this narrative, an enlightened central planner, be it the government or political parties or global institutions, designs social change in a way that both increases freedoms and enhances prosperity. Freedom and prosperity are both the result of some other force. As the leading comparative legal scholars Konrad Zweigert and Hein Kötz note, “the style of a legal system may be marked by an ideology, that is, a religious or political conception of how economic or social life should be organized”.1Konrad Zweigert and Hein Kötz, An Introduction to Comparative Law, third edition (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, Clarendon Press, 1998), 72. In this conception, freedom and prosperity are central to understanding the varieties of capitalism.

Hayek traces the differences between common and civil law to distinct conceptions of freedom. He distinguishes two views of freedom directly traceable to the predominance of an essentially empiricist view of the world in England and a rationalist approach in France: “One finds the essence of freedom in spontaneity and the absence of coercion, the other believes it to be realized only in the pursuit and attainment of an absolute social purpose; one stands for organic, slow, self-conscious growth, the other for doctrinaire deliberateness; one for trial and error procedure, the other for the enforced solely valid pattern”.2Friedrich A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), 56. To Hayek, the differences in legal systems reflect these profound differences in philosophies of freedom.

This hypothesis sounds plausible, until one runs down the list of possible candidates. An enlightened government can simultaneously affect political, economic, and legal freedoms, as well as impact directly the various components of prosperity like health, education, income, and equality between women and men. Such social revolutions are not present in the data, however. Progress tends to be gradual or cyclical with few discrete jumps. To the extent that such upward jumps are seen in the data, they are present in the former communist countries like Croatia and Georgia. Even there, it takes years for the effects on prosperity to become apparent. Improvements in both freedom and prosperity tend to follow a slow, methodical pattern; evolution rather than revolution. This evidence contradicts the idea of an all-out reformer.

There are many arguments for global convergence, one of which offers a simple explanation: globalization leads to a much faster exchange of ideas, including ideas about laws and regulations, and therefore encourages the transfer of legal knowledge. Globalization also encourages competition among countries for foreign direct investment, for capital, and for business in general, which must also apply some pressure toward the adoption of good legal rules and regulations.

This explanation—of centrifugal global forces at play over large parts of the sample period—fits well the reversal in freedoms that we see towards the end of the sample period. Globalization has stalled and even reversed, and with it the trends in freedom and prosperity have changed too. But even globalization is a proxy for the collective political philosophies in the major world economies. Hayek, as is often the case, could see further than most of us.

Simeon Djankov is policy director of the Financial Markets Group at the London School of Economics. He was deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. Prior to his cabinet appointment, Djankov was chief economist of the finance and private sector vice presidency of the World Bank.

Joseph Lemoine is the director of the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center. Previously, he was a private sector specialist at the World Bank. He advised governments on policy reforms that help boost entrepreneurship and shared prosperity, primarily in Francophone Africa and the Middle East.

Dan Negrea is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center. He was the State Department’s Special Representative for Commercial and Business Affairs between 2019 and 2021. In that capacity, he pioneered and led the Deal Team Initiative, a coordination mechanism between US government agencies. The initiative promotes business relations between US and foreign companies around the world.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: A college student takes part in a performance to show that he wants to study without being concern about soaring tuition fees at a candlelight rally demanding tuition fees cuts at the Cheonggye plaza in central Seoul June 10, 2011. Thousands of college students and supporting citizens on Friday continued a protest demanding South Korean President Lee Myung-bak fulfil his presidential election pledge to cut tuition fees by half, and provide solutions for youth unemployment. REUTERS/Jo Yong-Hak (SOUTH KOREA - Tags: EDUCATION POLITICS CIVIL UNREST BUSINESS EMPLOYMENT)