In the eleventh of a series of “IntelBriefs” on African security issues being produced by the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center in partnership with the Soufan Group, an international strategic consultancy, Africa Center Deputy Director Bronwyn Bruton draws attention to police persecution of Kenya’s Somali population and warns that a homegrown radicalization problem is brewing.

In the eleventh of a series of “IntelBriefs” on African security issues being produced by the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center in partnership with the Soufan Group, an international strategic consultancy, Africa Center Deputy Director Bronwyn Bruton draws attention to police persecution of Kenya’s Somali population and warns that a homegrown radicalization problem is brewing.

As of mid-October 2012, Somalis continue their longstanding regard for Ethiopia as an enemy at the gate. Somalia went to war with Ethiopia in 1977 and 1978 over irredentist claims, and Ethiopia is accused of ongoing human rights violations against secessionist Somalis living in its Somali (or “Ogaden”) Region. When the Union of Islamic Courts seized power in Somalia in 2006, Ethiopia plunged into a brutal two-year occupation of Mogadishu that enraged Somalis across the globe.

Unconventional Wisdom

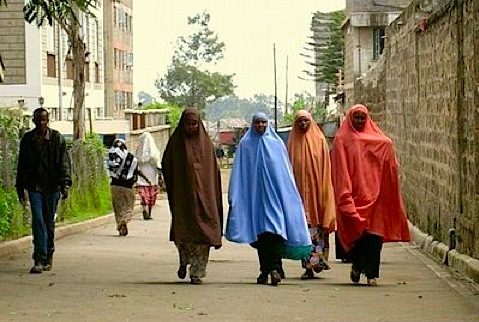

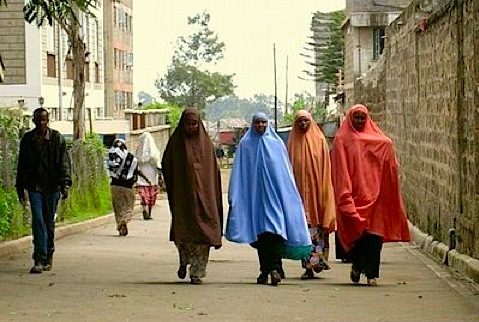

In contrast, Kenya has historically chosen to play the role of “good cop” in the Horn of Africa region. It has tolerated the creation of the world’s largest refugee camp on its Somali border, and permitted the Eastleigh neighborhood of Nairobi to become a kind of Somali investment Mecca. “Little Mogadishu,” as Eastleigh is widely known, has attracted tens of thousands of Somalis and US $billions of their investments. To many Somalis, it is a home away from home.

But the conventional portrait of Kenya as Somalia’s good neighbor is beginning to fade. Eastleigh has degenerated into a slum where Somali entrepreneurs increasingly feel ghettoized. Somali residents describe Eastleigh as a hunting ground for corrupt police, who shake down both legal and illegal Somali residents on a daily basis. The government has conducted a series of mass arrests, in which as many as several hundred Somalis at a time have been swept off the street and forced to bribe their way back to freedom. In the southern port of Mombasa, the August 27, 2012, assassination of a radical cleric, Sheikh Aboud Rogo Mohammed, who had urged Muslims to take up arms against the Kenyan government in retaliation for the Kenyan Defense Force’s intervention in Somalia in late 2011, triggered days of rioting amid widespread allegations that the Kenyan police and the United States organized the assassination. (A perception of regional marginalization had already created a secessionist movement — the Mombasa Republican Council — that is popular among both Christian and Muslim residents of the coastal city.) In Kenya’s North Eastern Province, the ethnic Somali population has suffered brutal attacks by Kenyan police officers in retaliation for terrorist killings on the border by the Somali militant group al Shabaab.

Coming in the midst of these domestic tensions, Nairobi’s decision to invade Somalia in October of last year in response to several cross-border incursions allegedly perpetrated by al Shabaab militants and its occupation last month of the heavily-contested Somali port of Kismayo has been perceived as an assault on Somali sovereignty, albeit one that also threatens to dangerously mire Kenya in Somalia’s intractable clan warfare.

Bringing Terror Home

Nairobi’s Muslim Youth Centre (MYC) is a product of these events. It was created in 2009, at around the same time that word of Nairobi’s plan to create a new mini-state in Somalia — a scheme known as the “Jubaland initiative” — began to spread across the Internet. Since then, the MYC has become a primary conduit of money and recruits to al Shabaab.

The MYC, also known as the “Pumwani Muslim Youth,” is not only partially a product of the disorder in Somalia, but also a symptom of the Kenyan government’s deteriorating relations with the Muslim segments of its own population — and the growing dissatisfaction of the country’s youth. The MYC has served as a gathering place for disgruntled youth and has openly advertised its commitment to jihad. But its recruits are not only drawn from traditionally Muslim groups; one of the most frightening aspects of Kenya’s homegrown radicalization trend is the number of non-Somali Kenyans, including Christians, who have converted to Islam and traveled to Somalia to fight with al Shabaab. (Over the last several years, Kenyan fighters have become the largest contingent in al Shabaab’s dreaded “foreign” ideologue faction.) These African equivalents of Omar Shafik Hammami (who is popularly known as Abu Mansoor al-Amriki, the rapper jihadist from Alabama) are among the most virulent advocates of jihadist violence and are less obvious targets of police scrutiny. They are also living proof that the threat of radicalization is not confined to the Somali community. The MYC and other radicals have clearly developed messages and recruitment methods that appeal to a broad array of youths.

As Somalia’s territory slips out of al Shabaab’s grasp, many of these Kenyan jihadi tourists are heading back home, and they may try to offer a safe haven for other foreign fighters. Al Shabaab’s hard-line former emir, Moktar Ali Zubeyr (a.k.a. “Godane”), is the driving force behind al Shabaab’s merger with al Qaeda, and is clearly attempting to position himself for a leading role in a revitalized al Qaeda in East Africa (AQEA). Kenya’s porous borders, corrupt police, and heavy international traffic offer opportunities for terrorists like Godane who are bent on destabilizing the region and targeting U.S. assets.

Stoking the Fire

Kenya’s restive tribal politics, unemployed youth, and widespread economic inequalities are potent fodder for jihadist propaganda. To mobilize a sizable corps of radical youth, jihadists will work to convince the Muslim community that they are worse off than the average Kenyan and that their problems are the result of deliberate government hostility or neglect. Unfortunately, that case is becoming easier to make.

In the wake of Kenya’s invasion of Somalia, a series of hand grenades were thrown into crowds in Nairobi. The attacks seemed ineffective and ad hoc, and surprised intelligence observers who expected that al Shabaab would be prepared to launch a more serious and coordinated attack. To date, a major terror attack has not materialized. But random terror incidents are occurring at a faster rate, and the Somali community is increasingly being swept up in the violence.

On September 30th, a day after the Kenyan capture of Kismayo, an explosive device went off during Sunday school at St. Polycarp’s, an Anglican church in Nairobi’s Pangani neighborhood, tragically killing a nine-year old child and injuring three others. Following the blast, a crowd of about hundred people attempted to stone individuals they took by appearance to be Somalis. Another set of coordinated blasts struck the immediate vicinity of the church on October 12th, implying that the perpetrators were deliberately targeting that area, perhaps in hopes of stoking further unrest.

That would be a clever strategy for al Shabaab, which is a depleted force in Somalia and may not be capable of a major terror attack on foreign soil. But if al Shabaab can goad Kenyan citizens into scapegoating average Somalis for the group’s terrorist misdeeds, a dramatic terror event may not be necessary to meet al Qaeda’s goal of radicalizing the population and creating a new foothold in East Africa.

Image: Photo: In2eastafrica