As Europe’s neutral states shift closer to NATO, Ireland approaches a turning point for its security

Bottom lines up front

- Irish Taoiseach Micheál Martin and Minister of Defense Simon Harris have proposed a staggering number of defense policy reforms, including raising defense spending to an all-time high.

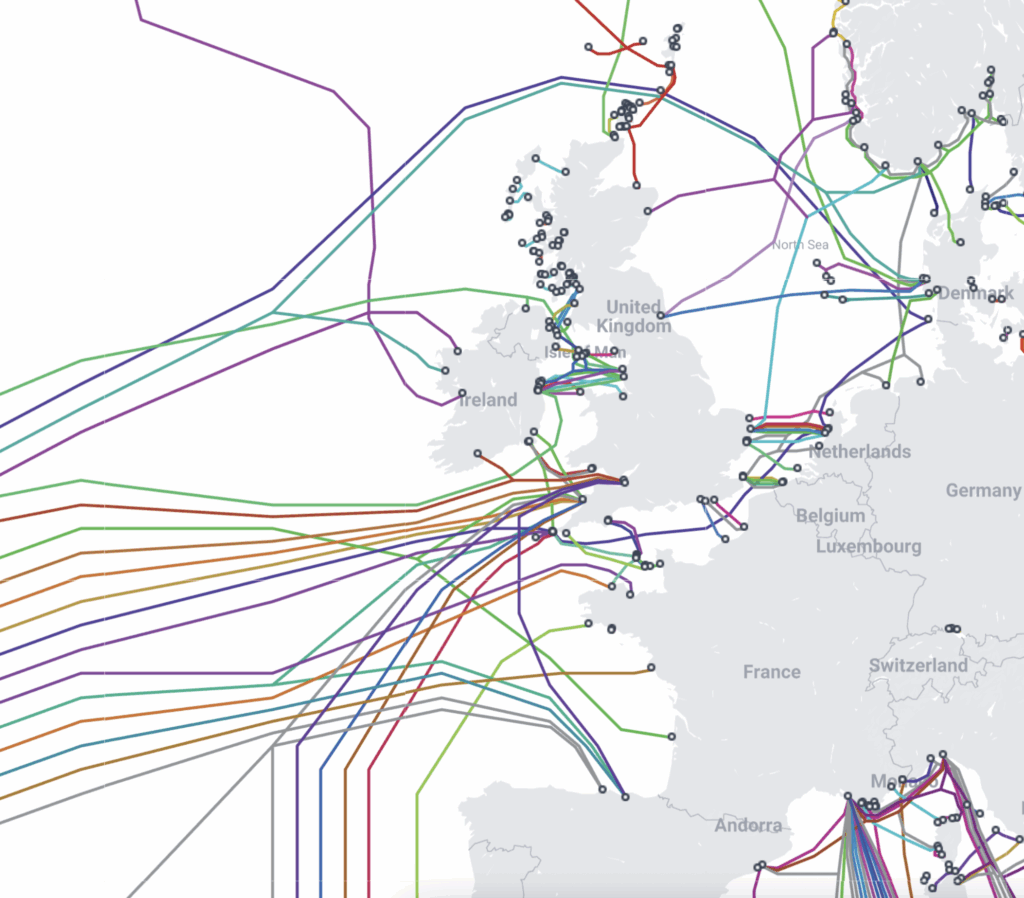

- Seventy-five percent of international data cables pass through or near Irish waters; to protect this critical communications infrastructure Dublin has just eight patrol ships.

- The government is clear that despite Ireland’s deeply engrained culture of neutrality the country needs a larger and more capable military—but the public may not yet be convinced.

In a further sign of the deteriorating security environment in Europe, the Republic of Ireland is rethinking the role of its military and its policy toward defense. Ireland’s renewed security discussion highlights the diminishing number of neutral or nonaligned countries in Europe in the wake of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Sweden and Finland’s 2023 decision to join NATO ended their centuries of military nonalignment. Even Austria and Switzerland, two countries synonymous with neutrality, have taken some steps toward condemning Russian aggression, such as Switzerland’s decision to host a NATO liaison office in Geneva. Although Ireland’s renewed security debate should not be misconstrued as an interest in NATO membership, it represents a timely reassessment of its security needs and a reconsideration of its geostrategic role in transatlantic security.

Ireland has historically been militarily neutral, but it is far from politically neutral. In recent months, Taoiseach (head of government) Micheál Martin has proposed a staggering number of defense policy reforms aimed at shoring up Ireland’s military and addressing potential vulnerabilities. This reassessment has also been hastened by the ongoing US reevaluation of its military presence in Europe. Ireland is entering a new era in its security and defense posture, spurred by Russian aggression, especially in the hybrid domain and critical undersea infrastructure. The consensus at the highest levels of government is clear—Ireland must do more to ensure its security in an increasingly complicated and uncertain world. Public opinion, however, may not have coalesced around this consensus.

The history of Ireland’s armed forces

Understanding Ireland’s armed forces today requires a look at the history of the island as it was shaped through numerous conflicts. Portions of the island of Ireland had been occupied by the English since 1169. As a result, Ireland’s military tradition is that of the rebel groups and paramilitaries who recurrently resisted colonial rule in several staggered uprisings and short conflicts. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) relied heavily on guerrilla fighting against the occupying English forces during the war; the IRA lacked training, standard weaponry, and force tactics. The period known as the Troubles (approximately 1966 to 1998) would see similar guerrilla tactics employed by Irish Republican paramilitaries during the 30 years of violence and unrest.

As World War II began, Ireland declared itself neutral but was sympathetic to the Allies and offered covert support. This policy of military neutrality dates back to the 1921 end of the Irish War of Independence, when the Irish Free State was established. As a result, Ireland was offered NATO membership by the United States in 1949, but declined the offer in order to maintain neutrality. To this day, the idea of NATO membership remains unpopular in Ireland, with 19 percent of the public in support and 49 percent opposed. Ireland continues to participate in NATO’s Partnership for Peace program, which allows some cooperation and interoperability.

Traditionally, Ireland has valued its role as a militarily neutral nation with a strong peacekeeping tradition, where it has gained a global reputation. Relative to the size of its military, Ireland has an unusually large role in global peacekeeping efforts and is the only nation to have a continuous presence on United Nations (UN) missions, which it has done since 1958. Ireland’s 2024 Defence Policy Review concluded that the country must adapt to the current geopolitical landscape while maintaining its commitment to military neutrality. Despite its peacekeeping tradition, Ireland’s military has been undersized and is reassessing its needs to ensure sovereignty in a more contested threat environment.

Ireland has faced scrutiny from security and defense analysts for its relatively low levels of military and defense spending. Despite the current government’s record-high defense budget of €1.35 billion ($1.48 billion) with a stated goal of increasing defense spending to €1.5 billion ($1.74 billion) by 2028, this still only accounts for 0.25 percent of Ireland’s gross domestic product (GDP). Ireland spends the least on defense out of any country in the European Union, despite having the second-highest GDP per capita in the bloc—its defense spending is only half that of fellow neutral state Malta, a country with about a tenth the population of Ireland. At the 2025 NATO Summit in The Hague, other European countries committed to spending 5 percent of their GDP on defense, further widening the gap between Ireland and its NATO-member neighbors when it comes to defense spending.

Part of the conversation around Ireland’s defense needs is focused on a worrying trend; like many European countries, Ireland is struggling to address personnel shortages. Obstacles for the Defence Forces include a lack of incentives for recruitment, poor rates of retention and low wages, and a lack of expertise in the officer corps. This confluence of wages, conditions, and lack of opportunities have led to what has been described as an “existential crisis” for Ireland’s military. For historical and cultural reasons, Ireland has never had a large military, and as a result, military service is an uncommon path for young people to choose. In 2022, the Commission on the Defence Forces reported 13,569 combined permanent and reserves, while the most recent reports indicate 9,900 combined forces. In 2025, Ireland’s military consists of approximately 7,400 active-duty personnel (5,950 Army, 750 Navy, 700 Air Corps) and 1,500 reservists (1,400 Army, 100 Navy). Ireland hopes to reverse this trend of personnel decline with a dramatic plus-up in the years ahead: Ireland’s permanent Defence Forces plans to grow to 11,500 by 2028. As the armed forces continue to struggle to retain the numbers needed to operate effectively, this growth will be difficult to achieve.

Evaluations and considerations of Ireland’s security posture

Central to Ireland’s contemplation of its security posture and needs are the government’s proposed reforms to the “triple lock” mechanism, a requirement since 1960 for the approval of troop deployment. To meet the triple lock requirement, three bodies must approve the deployment: the UN Security Council or General Assembly, the Irish government, and the Dáil, the directly elected lower house of the Irish parliament. Under the requirement, up to 12 members of the Irish Defence Forces can be sent on an overseas mission without triggering the lock. The proposed change would lift the UN approval requirement and allow up to 50 troops to be deployed without Dáil approval. Amending the triple lock is not without precedent. It was previously amended in 2006, allowing the UN General Assembly—not just the Security Council, where a veto is possible—to authorize Irish troop deployment. Amending the triple lock is contested; as many as 400 academics wrote a letter to Taoiseach Micheál Martin arguing that removing the lock would effectively end Ireland’s military neutrality. If the triple lock is amended, Ireland will find itself more capable of mobilizing when international peace or security is at stake. On the global stage, this would not impact perceptions of Ireland’s neutrality. The lock’s removal is more a question of Ireland’s internal discourse and self-perception.

The evaluations of Ireland’s 2024 Defence Policy Review place its current capabilities at what the review describes as Level of Ambition 1 (LOA 1). LOA 1 denotes that Ireland’s security forces would not be able to defend against a sustained military campaign against the nation. With increased defense spending agreed upon, Ireland has committed to moving to Level of Ambition 2 (LOA 2) Enhanced Capability for the Defence Forces. This next level would transition Ireland’s current capabilities to a large defense force, capable of defending Irish sovereignty and participating in high-intensity peace support, crisis management, and humanitarian relief operations abroad. Once LOA 2 is achieved, Level of Ambition 3 (LOA 3) Conventional Capability would be the next step, including upgrades to bring Ireland’s defense capabilities in line with similarly sized European countries. The Defence Policy Review identifies maritime capabilities and air surveillance as top priorities, given concerns over critical undersea infrastructure and increased foreign military activity in Ireland’s economic exclusion zone. The Irish Department of Defence has also established a new maritime strategy unit to address this security challenge, and plans to release an updated maritime strategy document in the near future.

Between revanchism and uncertainty

Echoing other European leaders at a March 2025 meeting of the European Council to discuss supporting Ukraine’s efforts to defeat Russia, Martin agreed that “Europe must do more to secure its own security and defense,” acknowledging “Ireland is not immune to these threats.” For its part, Ireland is in the process of hastening the procurement of a new primary radar and air defense system. Without a primary radar, Ireland is unable to track aircraft in its airspace. In April, the US Department of State approved a request for Ireland to buy Javelin launchers and missiles worth $46 million. The Irish Air Corps, meanwhile, has no fighter jets at its disposal, having retired its last one in 1998. The Air Corps otherwise largely consists of a handful of helicopters and planes, amounting to two maritime patrol aircraft, five small transport jets, and eight training aircraft. For the first time in 50 years, Ireland is weighing the acquisition of new fighter jets, at a projected cost of €2.5 billion. Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister) and Minister for Defence Simon Harris announced on February 28 the beginning of an exploration phase to acquiring at least eight combat jets, with a target of 12 to 14 aircraft, to “deter and detect airborne threats.” The government’s interest in the aircraft may also show a will to reduce dependencies on other countries for Ireland’s air surveillance and defense. Since the 1950s, a “secret pact” has existed between the United Kingdom and Ireland that would allow the Royal Air Force to intervene in Irish airspace in case of an incident. Ireland may not be able to count on this anymore, however, given the numerous pressing challenges identified in the UK’s new Strategic Defence Review, which did not mention the Republic of Ireland.

Despite being an island nation, Ireland’s navy largely consists of just eight patrol ships and no submarines, yet it is tasked with patrolling 16 percent of the EU’s territorial waters. Due to staffing shortages, as of 2022 not all ships were operable at once, necessitating the use of chartered private vessels to fill gaps. This was particularly apparent in January 2022 when the Russian navy conducted military exercises on the edge of Ireland’s territorial waters, over a region that holds the densest concentration of undersea cables linking North America and Europe. In recent years, there have been increased instances of sabotage against critical infrastructure in Europe, especially in the Baltic Sea. Gray-zone attacks on Europe attributed to Russia almost tripled between 2023 and 2024, 21 percent of which were on critical infrastructure. Maritime security is increasingly on the agenda, especially at NATO and in a transatlantic context, as Russia further probes for weaknesses in European waterways. Approximately 75 percent of data cables in the Northern Hemisphere pass through or near Irish waters; combined, they represent 95 percent of international data traffic. Outside of the multiple undersea cables that keep the island connected to the rest of the world, Ireland has offshore wind infrastructure that may also be vulnerable to sabotage. As a first step toward protecting undersea cables and offshore wind installations, Harris approved the Irish Defence Forces joining the Common Intelligence Sharing Environment, which will allow naval forces to exchange information and intelligence with 10 other European nations. Any intelligence-sharing arrangement for Ireland will augment its investment in its defense capabilities and allow it to more capably patrol its waters.

As the Irish government continues to push to strengthen Ireland’s defenses and military, Ireland has a difficult balancing act ahead: preserving its unique form of neutrality while rising to meet the challenges posed by the current security environment. Between a revanchist Russia and an uncertain United States, Ireland is facing a bold new era in its defense policies and a historic break in its own norms to meet future security needs.

About the authors

Maeve Drury most recently was a Joseph S. Nye Jr. intern for the Transatlantic Security Program at the Center for New American Security.

Jason C. Moyer is a nonresident fellow with the Transatlantic Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Related content

Explore the program

The Transatlantic Security Initiative aims to reinforce the strong and resilient transatlantic relationship that is prepared to deter and defend, succeed in strategic competition, and harness emerging capabilities to address future threats and opportunities.

Image: A military flyby passes over O'Connell Street during the commemoration of the hundred-year anniversary of the Irish Easter Rising in Dublin, Ireland, March 27, 2016. REUTERS/Clodagh Kilcoyne