Asking the right questions: Can digital currency enable financial inclusion?

Table of contents

Central bank narratives on financial inclusion

Industry narratives on financial inclusion

Expanding definitions: Financial inclusion and beyond

Towards a financial inclusion rubric for policymakers

Introduction

The story of cryptocurrencies is also the story of alternatives to the existing financial infrastructure—which, at the time of crypto’s birth in 2009–2010, was facing severe challenges. Bitcoin was a response to the loss of trust in banks and financial institutions, the first of its kind and an alternative way of sending and receiving value without touching the traditional financial infrastructure. In the decade since its birth, cryptocurrencies have shed their alternative or outsider status, and have entered the mainstream discussion about the future of money. Today, they are not only regularly used by traditional banks and financial institutions, but are also held by one in five Americans looking to invest and transact in bitcoin, ether, USD Coin, tether, and many others.1Thomas Franck, “One in 5 Adults Has Invested in, Traded or Used Cryptocurrency, NBC News Poll Shows,” NBC News, March 31, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/one-five-adults-invested-traded-used-cryptocurrency-nbc-news-poll-show-rcna22380. The technology behind them, decentralized ledger technology (DLT), has garnered the interest of governments, technology companies, and investors. However, along with their claims of technological disruption and next-generation products, the proponents of digital currencies often talk of their potential in terms of broadening inclusion and access. The popular term Web 3.0 reflects a suite of these potential applications of DLT, including the products, the technological and operational use cases, and the vision of the industry.

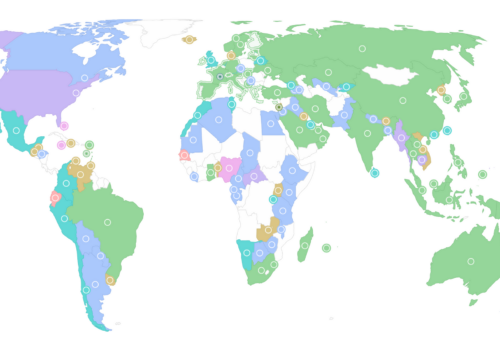

Concurrently, more than one hundred governments around the world are pursuing central bank digital currencies (CBDC), which are meant to provide a digital form of respective fiat currencies.2Central Bank Digital Currency Tracker,” Atlantic Council, last visited October 11, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/cbdctracker/. While the motivations of CBDC development differ across countries, financial inclusion is an oft-cited goal, along with reducing transaction costs and improving resilience and competition in the payments markets. Eleven CBDC projects are fully launched, and another eighteen are in the pilot stage.3Central Bank Digital Currency Tracker,” Atlantic Council, last visited October 11, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/cbdctracker/.

However, despite the growth of these CBDC projects in the last two years, adoption remains limited in the countries that launched them, and early data are inconclusive on whether the objectives set out have been achieved. Similarly, despite industry narratives about financial inclusion, most data on crypto’s use have little to do with its successes or failures in broadening financial access, and many projects that aim to expand financial access are in their infancy. Therefore, the claim of financial inclusion for digital currencies is difficult to prove quantitatively at the moment.

The absence of these data, from both the public and private sectors, has led to a gap in the research on financial inclusion motivations of DLT-based products. As the industry grows and CBDCs proliferate, policymakers must gain a deeper understanding of what financial inclusion means for a new generation of products, whether the definitions themselves are robust, and must undertake a goal-setting exercise and assessment of the claims against reality. Of course, this requires valuable data from the existing projects to evaluate these claims, but effectively evaluating and learning from the data also requires developing a benchmark for assessing the impacts on financial inclusion that these products can have. Put simply, we need to ask the right questions. Therefore, the central question of this issue brief is: what questions must be asked to assess the financial inclusion impacts of these products? In order to do so, this issue brief explores the narratives on financial inclusion provided by the proponents of digital currency—central banks that issue CBDCs and the Web 3.0 industry. It compares this set of claims against the conventional concepts of financial inclusion, and address where they fall short or expand existing understanding. It then seeks to develop a model of “asking the right questions”—that is, how to evaluate the financial inclusion benefits of these products across the stack.

Central bank narratives on financial inclusion

Financial inclusion is core to the functioning of central banks, which aim to provide equitable access to financial products, including fiat currencies. More than one hundred governments around the world are pursuing CBDCs, often by building upon decentralized ledger technologies, including blockchain.4Central Bank Digital Currency Tracker,” Atlantic Council, last visited October 11, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/cbdctracker/. While countries pursue retail CBDC projects for a variety of reasons, many of the motivations relate to furthering financial inclusion. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) notes: “CBDC could potentially facilitate financial inclusion by increasing access to digital payments and thus serving as a gateway to wider access to financial services.”5Gabriel Soderberg, et al., “Behind the Scenes of Central Bank Digital Currency: Emerging Trends, Insights, and Policy Lessons,” International Monetary Fund, February 9, 2022, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fintech-notes/Issues/2022/02/07/Behind-the-Scenes-of-Central-Bank-Digital-Currency-512174 The US Treasury Department, in its “Future of Money and Payments Report,” says: “A CBDC could serve the unbanked and underbanked by providing a low-cost, easily accessible alternative to existing private sector payment services.”6“The Future of Money and Payments: Report Pursuant to Section 4(b) of Executive Order 14067,” US Department of Treasury, September 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Future-of-Money-and-Payments.pdf.

A Bank for International Settlements survey on CBDCs and financial inclusion found that while some central banks view CBDCs as the “catalyst for innovation and economic development,” others view them as complementary to their other financial inclusion initiatives. 7Raphael Auer, et al., “Central Bank Digital Currencies: A New Tool in the Financial Inclusion Toolkit?” Financial Stability Institute (FSI) of the Bank for International Settlements, FSI Insights 41 (2022), https://www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights41.htm. Of the four largest central banks in the world, three have explicitly stated the potential for CBDCs to help with financial inclusion goals.8This includes reports and statements from the Bank of Japan, the US Federal Reserve, and the Bank of England. Thus, while the models vary, most countries embarking on CBDC research do so with an explicit or implicit aim of broadening financial inclusion.

When it comes to financial inclusion, the main proposition of central banks is to provide a method of improved and expanded access to fiat currency. However, there is little proof to substantiate this motivation in existing CBDC projects. Take the example of e-Naira, which was launched in Nigeria in October 2021. As with other central banks, financial inclusion is a top claim on the Central Bank of Nigeria’s website: “eNaira provides financial inclusion by making financial services available to people or communities that do not have (enough) banking opportunity.”9“Same Naira. More Possibilities,” eNaira, Central Bank of Nigeria, last visited October 11, 2023 , https://enaira.gov.ng/. Despite this, access to eNaira is currently limited to those with existing bank accounts, though there is an ongoing effort to provide access to those without accounts in the future. This is a critical problem for a country in which 55 percent of its total population is unbanked.10 Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19,” World Bank, 2022, https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-4. Therefore, the eNaira rollout has left out the majority of Nigerians. It has also proved to be unpopular among them: early numbers indicate that only one in two hundred Nigerians, or 0.5 percent, actively use it.11Anthony Osae-Brown, Mureji Fatunde, and Ruth Olurounbi, “Digital-Currency Plan Falters as Nigerians Defiant on Crypto,” Bloomberg, October 25, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-10-25/shunned-digital-currency-looks-for-street-credibility-in-nigeria?sref=323RPL5z.

Research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Digital Currency Institute has found a similar lack of practical examples of financial inclusion in CBDC rollouts. The paper’s claim that “CBDC is not a specific payments instrument with common attributes across countries but rather reflects a broad range of instruments that could differ significantly in features and functions,” is largely true.12Neha Narula, Lana Swartz, and Julie Frizzo-Baker, “CBDC: Expanding Financial Inclusion or Deepening the Divide? Exploring Design Choices That Could Make a Difference,” MIT Digital Currency Initiative, January 12, 2023, https://dci.mit.edu/cbdc-fi-1. That comes with a caveat, as (many specific differences aside) most CBDC projects are looking at two-tier intermediation solutions, which include interaction with a bank account for CBDC access, as in the case of eNaira.13“Same Naira. More Possibilities.” However, the paper found that emerging digital-currency technology can offer alternatives to the two-tier intermediation model, thereby expanding access to CBDCs. Meanwhile, other findings on barriers to financial inclusion—such as lack of digital identification, connectivity, and interoperability—illustrate the specific financial inclusion concerns for central banks. Increasingly, central banks are experimenting with offline transactions, incorporating digital-ID frameworks and even providing different custodial models, getting to central banks’ fundamental goal of improving and expanding access to fiat.

Industry narratives on financial inclusion

Private companies that issue, store, enable transfers, and build infrastructure for cryptocurrencies and stablecoins (which are fiat-pegged cryptocurrencies) are collectively referred to as the Web 3.0 industry. The industry narratives about how their products can enable financial inclusion are centered around two main claims. First, companies argue that the decentralized nature of their products offers advantages when compared to centralized financial institutions like banks, primarily because it reduces the often-higher intermediation costs of the legacy-payments architecture.14Oliver Wyman. “Digital Assets and Web3: The Future of Finance.” February 2023. Companies claim that decentralization allows for the free and open flow of money globally. The claim of decentralization is used as more than a proxy for technological differences; it also substitutes for claims of an anti-competitive marketplace in financial and technology services.15Bank for International Settlements. “Central Bank Digital Currencies: Foundational Principles and Core Features.” BIS Working Papers No. 1066, November 2021. https://www.bis.org/publ/work1066.htm Companies thereby also claim that their products and services improve markets by inducing competition and improving consumer welfare. In sum, cost reduction is a major financial inclusion benefit offered by digital currencies.

Decentralization vs. Centralization

“Centralization” refers to a system of control and authority by a sole entity. “Decentralization” refers to the transfer of control and decision-making to many different entities, which make decisions through mutual agreement or consensus. In the context of finance, decentralization often refers to the removal of intermediaries to enable transactions between people. Decentralization technologically relies on distributed-ledger technology (as opposed to centralized ledgers), which can separate the ledger governance and settlement features to enable a transaction. This is particularly useful to parties that do not trust each other or want to build greater transparency, as well as in cases where there are particular privacy and cybersecurity vulnerabilities to digital infrastructure.

Second, companies claim that their products offer a lower barrier of entry than traditional financial products.16World Economic Forum. “How Cryptocurrencies Can Advance Financial Inclusion – And How to Help Shape It.” June 2021.https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/cryptocurrencies-financial-inclusion-help-shape-it/ This can include the ability to transact without bank accounts or to access credit without financial history. This, again, goes to the goal of improving and expanding access, which is shared by central banks. Both CBDCs and other DLT-enabled products offer other implicit financial inclusion benefits. First, the products that use DLT can significantly improve the speed of transactions, allowing for instant settlement times, which can reduce lag times in making payments. Second, factors such as reduced cash usage and increased customer preference for holding money in different forms have led to the need for digital options for traditional fiat, which can be achieved through CBDCs and DLT-enabled products. Thirdly, in many economies, economic volatility has created the need to establish alternative payment channels and stores of value, leading to the proliferation of Web 3.0-enabled products and services. This includes economies like Lebanon, where citizens are using cryptocurrency to protect their wealth against falling fiat and crumbling financial markets, and Ukraine, where Russia’s invasion has led to aid programs that send hundreds of millions in cryptocurrencies.17Ananya Kumar and Nikhil Raghuveera, Can Crypto Deliver Aid Amid War? Ukraine Holds the Answer, Atlantic Council, April 4, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/can-crypto-deliver-aid-amid-war-ukraine-holds-the-answer/,

The explicit inclusion claims of centrals banks and industry include improving access through incorporating the financially excluded—that is, including the unbanked and underbanked population through different custody arrangements and reducing costs—and their implicit inclusion claims include, for example, improving transaction speed, providing optionality, and alternative financial channels. Consequently, it is easy to understand why these products are targeted to those marginalized from the existing financial system: those without bank accounts or access to traditional credit and payments systems, those reliant on remittances, and those underserved by banks and other financial institutions. However, there is a need to evaluate these claims against the concept of financial inclusion as a whole, in order to provide appropriate comparisons for substantiation. The next section explores how these narratives by central banks and industry stack up against conventional understanding of financial inclusion.

Expanding definitions: Financial inclusion and beyond

Since 2011, the World Bank’s Global Findex Database has measured financial inclusion, and its data are used to track progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals. Its primary measurement is access to accounts, whether at a bank, credit union, or through a mobile-money provider.18Demirgüç-Kunt, et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021.” Indeed, account ownership can potentially provide a gateway into other kinds of financial services, such as loan provision. Over the years, account ownership has been impacted by a parallel technological development—mobile money—creating exponential growth in account ownership, especially in emerging economies in sub-Saharan Africa. Mobile-money accounts have also led to a new category of savings for many households, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where adults have reported saving alongside or solely in their mobile-money accounts. In addition to mobile money, digital bank transfers are increasingly becoming the norm for public- and private-sector wage payments, government transfers, and cross-border remittances.19Demirgüç-Kunt, et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021

Despite account ownership with financial institutions and mobile-money providers steadily rising since 2011, barriers such as lacks of liquid savings and credit access have persisted. Only 55 percent of adults in developing countries can access extra funds within thirty days, and more than 66 percent of adults in developing economies are worried about paying for emergencies.20Demirgüç-Kunt, et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021 Savings rates widely differ between developed and developing economies but, on average, only 28 percent of adults save using liquid accounts.21Demirgüç-Kunt, et al., “The Global Findex Database 2021. A majority of those adults save solely for short-term needs.

The latest Global Findex Database report focuses on digital payments, but it uses “mobile money” and “digital payments” as overly broad categories that contain a variety of products and services within them. Mobile-money accounts using M-PESA, a Kenyan provider, use retailers to convert cash into digital credits, which can be transferred using mobile-phone personal-identification number (PIN) confirmation.22“M-Pesa: How It Works,” Vodafone, last visited October 11, 2023, https://www.vodafone.com/about-vodafone/what-we-do/consumer-products-and-services/m-pesa#how-it-works. This looks very different from a Venmo account in the United States, which is often connected to a debit card or bank account. Another key difference is the architecture that enables these payments to go through. For example, India and Brazil have both popularized digital wallets using instant-payment networks for peer-to-peer payments, but a Venmo payment still relies on the automated clearinghouse (ACH) to complete settlements. 23Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. “What Is an ACH?”https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-an-ach-en-1065/

These differences across payment platforms, on both the front and back ends, create differential functions and costs, which can impact user behavior and interaction with these products. Similarly, factors such as access to internet connectivity or a mobile phone can also lead to different inclusion outcomes. Therefore, what a mobile-money account looks like, what services it can provide, and how it achieves those functions will determine how useful it can be in achieving financial inclusion goals. Many of these lessons are also integral to designing and assessing the impact of digital currencies.

Experts have argued that the financial inclusion goals of digital currencies must go beyond the current forms of money. Comprehensive values such as financial inclusion are difficult to measure and validate, and measuring benchmarks such as account ownership—even with its positive correlation with better outcomes—can provide a narrow perspective on inclusion. As we have seen, these data in isolation can fall short of explaining trends in consumer behavior and do not capture the complexity of an increasingly digitizing infrastructure. That is why some have called for a broader perspective on inclusion, informed by behavioral outcomes such as savings, credit use and access, and opportunities for investment and financial planning. A financial health, or FinHealth, score is one such measure that considers indicators such as responsible use of income (e.g., spending less than income and paying bills on time); sufficient liquid and long-term savings; credit access and manageability (e.g., having manageable debt and a prime credit score); and financial planning (including appropriate insurance and planning ahead).24Brenton Peck, “Global Financial Health Launch Decision: Send ’Em!” Financial Health Network, January 10, 2023, https://finhealthnetwork.org/global-financial-health-launch-decision-send-em/.

Others have called for a better understanding of customer needs through user surveys, in order to ascertain the functions of future-generation financial products. These surveys have found some aspects of digital currencies to be desirable—such as self-custody funds (e.g., noncustodial wallets), the ability to hold them oneself instead of relying on a third party, cost reduction, transparency and trustworthiness, and the ability to “build” several kinds of functions into a wallet.25Narula, Swartz, and Baker, “CBDC: Expanding Financial Inclusion or Deepening the Divide?” Ivy Lau, “Digital Currencies Could Boost Financial Health,” International Monetary Institute, April 5, 2022, http://www.imi.ruc.edu.cn/en/VIEWS/bfd86426c59c4bf48ec85f32488536f1.htm. They have also found that a lack of enabling infrastructure, trust, and financial illiteracy can actually deepen digital divides between those who are financially included and those who are not.26Narula, Swartz, and Baker, “CBDC: Expanding Financial Inclusion or Deepening the Divide?”

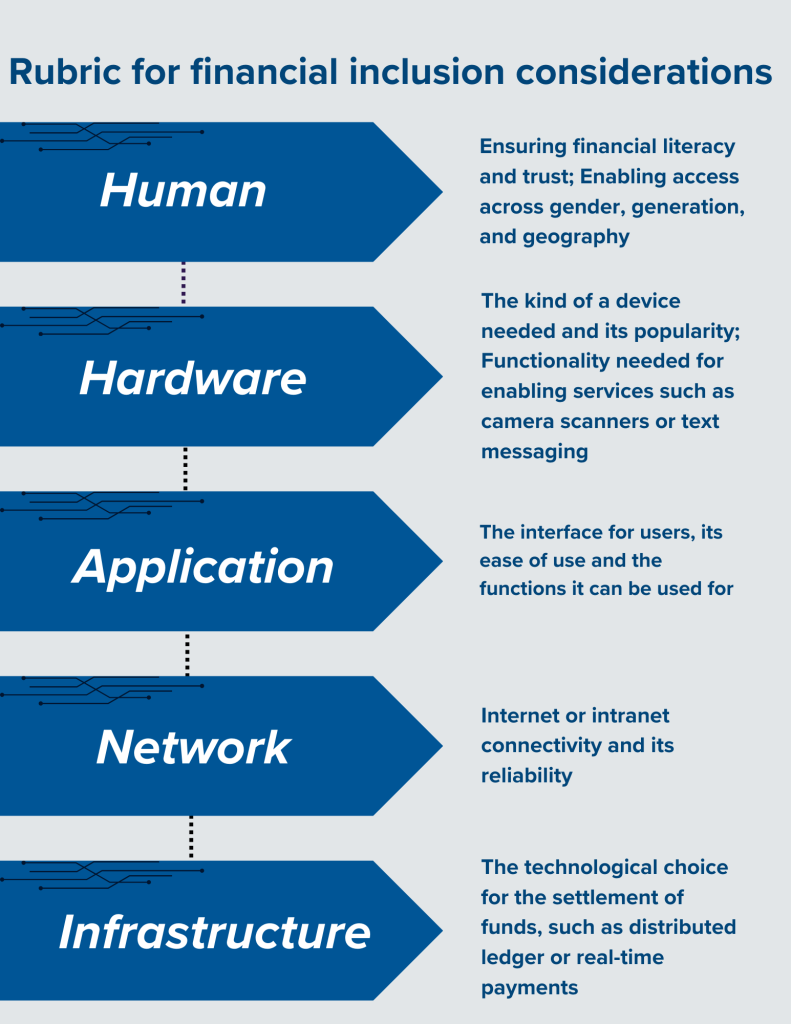

So what do these expanded definitions of financial inclusion mean for the fate of digital currencies seeking to bridge gaps? The good news is that because many of these projects are in their infancy, there is an opportunity to address the technical and policy aspects best suited to make them financially inclusive. The section below creates a rubric for policymakers designing these projects and assessing their impact.

Towards a financial inclusion rubric for policymakers

The last twenty years of mobile-money developments and the expanded definitions of financial inclusion can offer insights into what to consider while designing the next generation of financial products in order to achieve financial inclusion. There are several components that enable interaction between human beings and digital currencies, and the model below illustrates the layers of this interaction and the choices that designers must make across them in order to achieve financial inclusion. Each layer is accompanied by an inexhaustive list of considerations, which serve as a rubric for those involved in the creation of these projects as well as those interested in studying their impact.

Human layer: Although users are not a technical consideration, they often function as enablers in any mobile-money ecosystem. This applies across scenarios in which users seek each other’s help to successfully use an application and as they onboard their community to these networks, often functioning as vectors of trustworthiness. Issues such as lack of information or trust reside in the human layer. So do considerations across social differences, such as gender, class, or geography.

Considerations: How do we enable better financial literacy and education? How do women and men differ in their use of payments applications? How do people of different generations interact with digital currencies? Who do people go to when they have a question about their mobile-money applications? How much time do people spend learning how to use an application?

Hardware layer: Every digital currency will ultimately require a device, whether mobile phones, laptops, computers, or hardware wallets (usually in the form of microchip-enabled cards). Issues of access to hardware reside in this layer.

Considerations: What kind of a device does the digital currency run through: a phone, card, smartphone, or laptop? What kind of function does a device need in order to be usable: does it have a camera to scan QR codes or a text-messaging service? How many people have access to it? Can it work through a shared device? Is it accepted by all merchants in an area?

Application layer: Once people connect to their accounts through a phone, they will look for an application to interface between their money and how they would use it. This can be for something as simple as looking at account balances or something as complicated as a wallet that allows for government payments like Social Security or tax refunds.

Considerations: How can the user be onboarded to the application? Does it require a digital identification? How easy is the application to use? How much time will the customer spend to file a complaint, if needed? What functions does it provide? Can it track users’ savings? Can it enable automatic payments? Can it determine credit scores? Can it track debt payments?

Network layer: This layer determines how the application communicates with the rest of the infrastructure. This can use the internet in the form of broadband connection or telephone connectivity.

Considerations: How many people have access to broadband networks? Do networks need to be expanded to achieve the benefits? How reliable is the connectivity to phone networks? Can hard-to-reach areas be covered through the application? If not, is there an offline version that can work reliably?

Digital identity

The digitization of identity refers to the movement away from physical forms of identity, such as a traditional driver’s license, and toward personal data accessible in electronic form for identification. This can include things like biometric identification, phone numbers, digital records, etc. As economic activities move online, trustworthy forms of digital ID need to be created and recognized. Countries like India, Ukraine, Nigeria, and Brazil have experimented with different kinds of digital IDs. India’s Aadhar is the world’s largest biometric system. Since its inception, Aadhar has provided a recognized form of identification to 94.2 percent of India’s population, which, in turn, has helped boost digital finance and subsidy distribution, and has created measurable economic value for India’s economy. Aadhar is not free from controversy, as it is often accused of privacy breaches and infrastructural vulnerabilities by the state. India continues to build a digital stack using the Aadhar infrastructure.

Digital IDs can be fraught with concerns regarding unauthorized surveillance and data leakages by the state and the private sector, making them a controversial topic globally. Privacy-centered, secure, and interoperable forms of digital IDs are necessary to unlock real economic value and to provide seamless forms of interaction between states, the private sector, and individuals. Trustworthiness, therefore, is the ultimate test for building and using digital IDs in the future.

Infrastructure layer: This refers to the back-end technology of the application. As discussed previously, depending on the technology choice, products can be made faster, cheaper, or safer, which will impact user behavior. Some of these technology choices are informed by the private sector, while others—such as national payments infrastructure—can be a public-sector endeavor.

Consideration: Does the application use distributed-ledger technology? Can it handle large volumes and scale of payments? Does it rely on fast-payments infrastructure, which can settle payments in less than twenty-four hours? Can it offer better transparency into the flows of money? Does it eliminate or lower costs?

While these considerations can provide a blueprint for better-designed products that account for expansive definitions of financial inclusion, the success of financial products ultimately depends on local factors and policy. The lesson from the success of M-PESA or Alipay is that some kinds of digital currencies will be more successful because they address specific user needs in certain geographies. Introducing internet-enabled digital currency in a country or region with low levels of access to the internet will not provide the best results. Similarly, requiring digital IDs for “know your client” (KYC) rules in countries with low levels of ID infrastructure will be counterproductive. Therefore, considerations need to be adjusted for local needs, and the resulting products will look different from one place to another.

Secondly, national and regional policies can actually bridge the gaps when it comes to access. For example, policies that enable more access to mobile phones can yield beneficial financial inclusion results. So can public education programs that address financial fraud and provide basic financial literacy. Similarly, economic policies that can control for volatility and inflation can enable trust and ensure sustainable, liquid avenues of income, spending, and borrowing. By themselves, products can do very little if national and regional policies aren’t working in tandem toward the goal of financial inclusion. Sound policy and local perspectives are, therefore, significant steps toward the goal of financial inclusion.

Policy lessons

One challenge in creating this paper was the limited amount of quantitative data proving the claim of financial inclusion underlying the developments in private and central bank digital currencies. There is an acute need for the private and public sectors to provide credible data in order to assess the impact of digital currencies on financial inclusion, so more experimentation and testing for CBDCs and private digital currencies are a valuable first step. The second consideration is how to assess these experiments. We have discussed the industry and public-sector narratives claiming potential benefits, and compared these claims to conventional understanding of financial inclusion. In doing so, we found the definitions of financial inclusion to be too narrowly focused on benchmarks such as account ownership.

We find that digital currencies can be desirable in expanding the definition of financial inclusion to include user behavior and outcomes. Given that most of these projects are in the research, development, or pilot stages, there is an opportunity to build them in a way that enables financial inclusion. The resulting rubric for financial inclusion addresses the central question of this paper: what questions must we ask in order to assess products’ financial inclusion impacts? By separating the components of the digital currency ecosystem, we provide financial inclusion considerations across the stack, which can serve as a checklist for those designing and those studying the impact of these products. Finally, policymakers must consider the local factors at play, as well as broad national and regional policies, in order to fully realize the financial inclusion potential of these products. The runway on digital currency development is long, but central banks and private companies considering these products must ensure they are designed to achieve gains in financial inclusion and, ultimately, drive adoption and impact.

Related content

About the author

Ananya Kumar is the associate director for digital currencies at the GeoEconomics Center. She leads the Center’s work on the future of money and does research on payments systems, central bank digital currencies, stablecoins, cryptocurrencies, and other digital assets. Her analysis has been cited by the Economist, Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, Federal Reserve, International Monetary Fund and World Bank. She holds a MA in strategic studies and international economics from SAIS, where she was a Merrill Center fellow. Kumar graduated cum laude from Bryn Mawr College with a BA in economics and political science.