Economic sanctions have proven to be an important foreign policy tool for the Trump Administration. In less than a year, it has expanded existing economic sanctions in response to disputes with North Korea, Russia, Cuba, Iran, and Venezuela. In Secondary Economic Sanctions: Effective Policy or Risky Business, author John Forrer, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Business & Economics Program, explains that one specific strategy used to increase the effects of US sanctions is referred to as “secondary sanctions.” This type of sanction is adopted in addition to the “primary sanctions” imposed on a sanctioned individual or entity. The author adds that globalization has lessened many countries’ vulnerability to traditional sanctions, and poses severe challenges to designing and implementing economic sanctions. Mr. Forrer argues that secondary sanctions can bolster the effectiveness of primary sanctions. At the same time, he cautions that secondary sanctions can be controversial, and their effectiveness is highly contested. The author stresses the importance of fully understanding secondary sanctions’ promise and pitfalls, before embracing a strategy of expanded use of this foreign policy tool.

Economic sanctions initiative

Economic sanctions have become a policy tool-of-choice for the US government. Yet sanctions use, and potential pitfalls, are often misunderstood. The Economic Sanctions Initiative seeks to build better understanding of the role sanctions can and cannot play in advancing policy objectives and of the impact of sanctions on the private sector, which bears many of the costs of implementing economic sanctions.

Introduction

Economic sanctions have proven to be an important foreign policy tool for the Donald Trump administration. In less than a year, it has expanded existing economic sanctions in response to disputes with North Korea, Russia, Cuba, Iran, and Venezuela. The US State Department is considering new sanctions targeting Myanmar for its treatment of the Rohingya community, under the authority of the Global Magnitsky Act.1Scott Neuman, “Amid Rohingya Crisis, White House Mulls Sanctions on Myanmar’s Military,” NPR, October 24, 2017, http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/10/24/559678945/amid-rohingya-crisis-white-house-mulls-sanctions-on-myanmars-military. This law authorizes the United States to freeze assets and impose visa bans on selected individuals for violations of international human-rights standards.

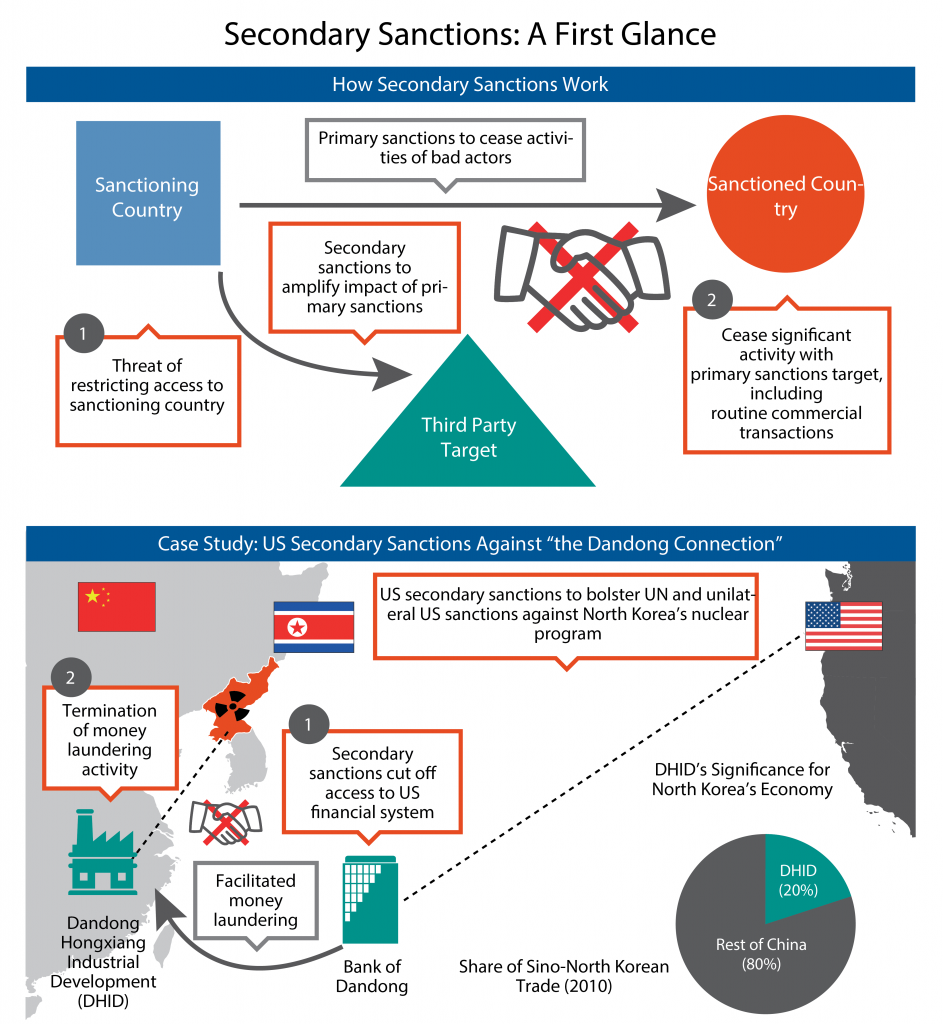

One specific strategy used to increase the effects of economic sanctions on North Korea and Russia is referred to as “secondary sanctions.” This type of sanction is adopted in addition to the “primary sanctions” imposed on a sanctioned country, organization, or individual, and it has very specific characteristics. Globalization has lessened many countries’ vulnerability to traditional economic sanctions, and poses severe challenges to designing and implementing economic sanctions that result in economic suffering for the targeted constituencies within the sanctioned country.2John Forrer, Aligning Economic Sanctions (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2017), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/issue-briefs/aligning-economic-sanctions. Looking to secondary sanctions to bolster the effectiveness of primary sanctions may be one approach to addressing the less-than-anticipated consequences of some economic-sanction regimes. At the same time, secondary sanctions can be controversial, and their effectiveness is highly contested. Before embracing a strategy of expanded use of secondary sanctions, it is important to fully understand their promise and pitfalls as a foreign policy tool.

There are several ways a sanctioning country can attempt to increase sanctions’ effects after they have been imposed, including the adoption of secondary sanctions

What are secondary economic sanctions?

The term “secondary sanctions” is itself confusing and confused. It suggests that a class of economic sanctions exists that could be added to the original, “primary,” sanctions, but secondary sanctions involve more than introducing additional economic sanctions to intensify the consequences on the sanctioned country. There are several ways a sanctioning country can attempt to increase sanctions’ effects after they have been imposed, including the adoption of secondary sanctions.

1. Expand the scope of targets.

The sanctioning country can intensifyeconomic sanctions’ effects by expanding their scope: banning additional products from importation or exportation, expanding the list of individuals facing travel restrictions, or freezing additional assets. For example, President Barack Obama signed and issued a presidential order on March 9, 2015, declaring Venezuela a threat to US national security. Seven Venezuelan officials were named and sanctioned for violations of Venezuelans’ human rights. President Obama said, “We are deeply concerned by the Venezuelan government’s efforts to escalate intimidation of its political opponents.”3Jeff Mason and Roberta Rampton, “U.S. Declares Venezuela a National Security Threat, Sanctions Top Officials,” Reuters, March 10, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-venezuela/u-s-declares-venezuela-a-national-security-threat-sanctions-top-officials-idUSKBN0M51NS20150310. On August 25, 2017, the Trump administration imposed additional economic sanctions on Venezuela, which restrict the Venezuelan government’s selling of its bonds in US financial markets. The additional sanctions are a modest expansion, as they include several exemptions affecting the petroleum sector.4Clifford Krauss, “White House Raises Pressure on Venezuela With New Financial Sanctions,” New York Times, August 25, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/25/world/americas/venezuela-sanctions-maduro-trump.html. Expanding the scope of economic sanctions provides sanctioning countries the flexibility to ratchet up or down the effects of economic sanctions, in response to changing circumstances inside the targeted country and/or US expectations for sanctions’ effects.

2. Increase multilateral participation.

The sanctioning country can solicit additional countries to participate in the economic sanctions regime. The effort can be undertaken as a matter of foreign diplomatic efforts, or coordinated through the United Nations (UN). For example, the UN has adopted sanctions against North Korea on nine different occasions, beginning in 2006.5Grant T. Harris, “The U.S. Needs Real Diplomacy to Counter North Korea in Africa,” Foreign Policy, October 3, 2017, http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/10/03/the-u-s-needs-real-diplomacy-to-counter-north-korea-in-africa/. While the UN actions have expanded the scope of the sanctions, passing a UN resolution does not guarantee participation by all nations. For example, North Korea has many lucrative ties with African nations. These relationships were formed in the 1960s, when North Korea supported African nations’ struggles against colonialism, but have evolved into commercial relationships, with North Korea selling military equipment or sending laborers to African trading partners. While some African nations appear to have complied with UN sanctions, many of the financial ties have endured, and have proven difficult for the international community to monitor.6Adam Taylor, “The U.S. Extended Sanctions on Sudan—but North Korea Might be the Real Target,” Washington Post, July 12, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/07/12/the-u-s-extended-sanctions-on-sudan-but-north-korea-might-be-the-real-target/?utm_term=.2b907db461fd. The Trump administration has applied diplomatic pressure to African countries, and others, to adhere to those UN sanctions. The recent lifting of US economic sanctions against the Sudan has been linked to its commitment to sever ties with North Korea.7Ibid.

3. Impose extraterritorial economic sanctions.

The sanctioning country can extend its economic sanctions policy to apply to foreign-based firms outside of its jurisdiction. A well-known example is the Helms-Burton Act, which President Bill Clinton signed it into law in March 1996 as the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act. The legislation tightened the conditions of the existing economic embargo against Cuba. It provided for penalties on foreign-owned (non-US) companies that engaged in the “wrongful trafficking in property confiscated by the Castro regime” through trade with and investment in Cuba.8US Congress, “An Act to Seek International Sanctions Against the Castro Government in Cuba, to Plan for Support of a Transition Government Leading to a Democratically Elected Government in Cuba, and for Other Purposes,” March 12, 1996, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-104publ114/html/PLAW-104publ114.htm. The Helms-Burton Act required US multinational corporations to extend their compliance practices to their foreign-based subsidiaries. The act was met with protests from countries where the foreign subsidiaries were located, which viewed the sanctions as illegal.

4. Impose secondary sanctions.

The sanctioning country can prohibit firms and individuals in other countries from conducting commercial transactions with US citizens and businesses, to inhibit their economic relationship with the country targeted with “primary” economic sanctions. A contemporary example is the secondary sanctions the United States has placed on Chinese firms and individuals for undertaking financial transactions with North Korea. On June 19, 2017, the United States imposed sanctions on a Chinese bank (Bank of Dandong), a Chinese firm (Dalian Global Unity Shipping Co.), and two Chinese citizens (Sun Wei and Li Hong Ri). The Bank of Dandong is banned from conducting any banking with US-based firms. Dalian Global is banned from commercial transactions with US firms and citizens. For Wei and Ri, the sanctions froze their assets and banned them from any business with US-based firms or individuals.9Zeeshan Aleem, “Why Trump Just Slapped New Sanctions on Chinese Banks,” Vox, June 29, 2017, https://www.vox.com/world/2017/6/29/15894844/trump-sanctions-china-north-korea-bank.

Extraterritorial sanctions versus secondary sanctions

Researchers and practitioners often equate extraterritorial and secondary sanctions, but there is an important distinction. Extraterritorial sanctions seek to impose adherence to economic sanction restrictions on entities located outside the sanctioning country’s borders. Such provisions are not uncommon, and were included in sanctions adopted by the United States against Cuba, North Korea, China, and Vietnam during the Cold War era. During the Ronald Reagan administration, the use of extraterritorial sanctions became controversial when they targeted European allies at odds with US objections to the construction of a natural-gas pipeline. In 1982, President Reagan imposed extraterritorial sanctions that prohibited foreign subsidiaries of US companies from providing parts and services for the construction of a pipeline linking the Soviet Union to Western European customers. A number of European countries objected to these measures, claiming they were illegal under international law because they were improperly “extraterritorial.” The US government eventually reversed course, and no longer applied these prohibitions to foreign subsidiaries of US firms.10Brian Egan and Peter Jeydel, “Back to the Future on ‘Extraterritorial’ Sanctions on Russian Pipelines,” Steptoe International Compliance Blog, June 26, 2017, https://www.steptoeinternationalcomplianceblog.com/2017/06/back-to-the-future-on-extraterritorial-sanctions-on-russian-pipelines/

Extraterritorial sanctions have also raised concerns that they violate World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. In 1996, the European Union initiated a WTO proceeding against the United States over extraterritorial aspects of the Helms-Burton Act. The same act led the EU, Canada, and others to pass so-called “blocking” statutes that prohibited companies within their jurisdictions from complying with the US sanctions program against Cuba. The WTO dispute was resolved, in part, by a 1998 understanding reached between the Clinton administration and the European Commission, in which both sides committed “not to seek or propose,” and to resist, “the passage of new economic sanctions legislation based on foreign policy grounds which is designed to make economic operators of the other behave in a manner similar to that required of [the partner’s] own economic operators.”11Ibid. Extraterritorial sanctions remain a contested foreign policy strategy. Once imposed, the countries where such sanctions take effect have passed their own counter legislation prohibiting their own firms from adhering to the sanctions requirements, leading to a standoff.

The “Dandong Connection” underscores how the US government is using secondary sanctions to put pressure on the North Korea’s government. On Novembzer 2, 2017, the US Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) prohibited US financial institutions “from opening or maintaining correspondent accounts for, or on behalf of, [the Chinese] Bank of Dandong”12Ammari, K., Carhart, M. J., Delich, J., Meyerson, E. J., Newton, J., Rosenbaum, M. J., … Vaid, K. (n.d.). “Economic Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Developments: 2017 Year in Review.” Lexology, January 23, 2018, https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=9e8a1e21-5d0d-4f14-b20a-5f27f41d4c1d. In June of 2017, FinCEN had ruled that the Bank of Dandong was violating section 311 of the US Patriot Act by laundering money for the Chinese trade conglomerate firm Dandong Hongxiang Industrial Development (DHID), which, in turn, had run a money laundering scheme for the North Korean government. The US Department of Justice had indicted DHID in 2016 for violating US sanctions by facilitating money transactions for the North Korean regime This was a significant step as the DHID is responsible for a large share of Sino-North Korean trade.

Following its secondary sanctions playbook, the US government made an example of the Bank of Dandong case to deter more significant Chinese banks and financial intermediaries located in other countries from conducting financial transactions with North Korean entities.

Marshall S. Billingslea, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorist Financing, remarked in his testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee that the imposition of secondary sanctions against Dandong Bank was “the Treasury Department’s first action in over a decade that targeted a non-North Korean bank for facilitating North Korean financial activity […]. Financial institutions in China, or elsewhere, that continue to process transactions on behalf of North Korea should take heed.”13Ibid.

Visit the Atlantic Council website for more Econographics on topics such as Brexit, blockchain technology, and the Italian elections.

Alternatively, secondary sanctions do not attempt to force foreign subsidiaries to follow a sanctioning country’s policies. The sanctioning country restricts its own firms and/or citizens from having commercial dealings with designated firms or individuals who refuse to follow US economic sanctions policy. Denying foreign-based firms and individuals access to domestic trade and financial markets is clearly within nations’ rights. Secondary sanctions are a tactic to apply pressure to other countries to align with the sanctioning country. On September 21, 2017, President Trump announced additional secondary sanctions in an effort to intensify the economic consequences for North Korea. Under that executive order, the US Treasury Department will prohibit access to US markets to any businesses or individuals trading or conducting finance with North Korea. Trump declared that the action would force other nations and foreign businesses to make a choice: “Do business with the United States…or the lawless regime” of North Korea.

Extraterritorial economic sanctions are also a tactic to compel countries to adopt the sanctioning country’s policies, and attempt to force firms in other countries to adopt specific practices regarding the sanctioned country. Secondary sanctions, however, take a different approach: failure to adhere to economic sanctions means denied commercial relations with the sanctioning country.

At their core, secondary sanctions should be seen as a means to enhance and/or expand multilateral sanctions. Only rarely will unilateral sanctions be successful in creating sufficient economic losses for the sanctioned country14.John Forrer, Economic Sanctions: Sharpening a Vital Foreign Policy Tool (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2017), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/issue-briefs/economic-sanctions-sharpening-a-vital-foreign-policy-tool. Persuading other nations to join in imposing sanctions against the target country strengthens the sanctions’ effects and, thereby, their prospects to be effective. In essence, secondary sanctions impose a cost on other countries (reduced access to commercial relationships with the sanctioning country) for withholding their full or partial support for sanctions. However, secondary sanctions face significant limitations. Imposing secondary sanctions on a few firms and/or individuals is not likely to create enough economic distress to overcome a country’s reluctance to participate in economic sanctions. Conversely, expanding secondary sanctions, to a point where economic losses become significant, could produce real acrimony. It can make declining to participate in economic sanctions a way of demonstrating a country’s sovereignty and, perhaps, of causing problems for the sanctioning country in other areas of international relations.

When do secondary sanctions work?

Any economic sanctions regime—unilateral, multilateral, extraterritorial, or secondary—is only a tool to advance foreign policy goals. There is no logical presumption for success, unless economic sanctions are aligned to cause the level of economic suffering in the sanctioned country believed necessary to bring about a change in its policies. There is a profound divide between academics and practitioners over the efficacy of secondary sanctions. Traditionally, the overwhelming consensus among researchers has been that secondary sanctions are not an effective foreign policy tool.15Richard N. Haass, “Economic Sanctions: Too Much of a Bad Thing,” Brookings, June 1, 1998, https://www.brookings.edu/research/economic-sanctions-too-much-of-a-bad-thing/; Richard N. Haass, “Sanctioning Madness,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 1997, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/1997-11-01/sanctioning-madness; Kimberly Ann Elliott and Gary Clyde Hufbauer, “Same Song, Same Refrain? Economic Sanctions in the 1990’s,” American Economic Review vol. 89, no. 2, 1999, pp. 403–408, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ee8e/fa88f77c88a7b6dd7119841af80e930d7963.pdf; Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Barbara Oegg, “Economic Sanctions: Public Goals and Private Compensation,” Chicago Journal of International Law vol. 4, no. 2, 2003, p. 305, https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol4/iss2/6/; Paolo Spadoni, Failed Sanctions (Gainesville, Fla.: University Press of Florida, 2010); Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, Kimberly Ann Elliott, and Barbara Oegg, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered (Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 1990); Robert A. Pape, “Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work,” International Security vol. 22, no. 2, 1997, pp. 90–136, https://web.stanford.edu/class/ips216/Readings/pape_97%20(jstor).pdf; Kinka Gerke, Unilateral Strains on Transatlantic Relations: US Sanctions Against Those Who Trade With Cuba, Iran, and Libya, and Their Effects on the World Trade Regime (Frankfurt: Peace Research Institute, 1997). The reasoning and findings in support of this conclusion parallel the evidence on the effects of unilateral economic sanctions.

- Rarely are the economic losses from the secondary sanctions large enough to change a country’s policy.

- The sanctioned country’s government/regime often uses the sanctions to consolidate political power, by demonizing the sanctioning country and raising national pride.

- Sanctions are directed at policies that the sanctioned country is unlikely to revoke under any circumstances, short of regime change.16Even the overthrowing of a government is no guarantee the new regime will adopt the sanctioning countries’ preferred policies.

- The sanctions have negative consequences for individuals and firms, while producing no foreign policy benefits.

- They are difficult to enforce, and therefore cause economic suffering—often for innocent populations—with weak prospects for success.

Many researchers view secondary sanctions as having all the worst attributes of economic sanctions, plus the added onerousness of potentially instigating new conflicts with allies and adversaries who object to the imposition of restrictions and economic hardship on their own industries and citizens. A few scholars are more enthusiastic about the prospects for secondary sanctions to be used effectively, while acknowledging the risks of potentially worsening relationships with allies.17George E. Shambaugh, States, Firms, and Power: Successful Sanctions in United States Foreign Policy (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1999); George A. Lopez and David Cortright, “The Sanctions Era: An Alternative to Military Intervention” Fletcher Forum of World Affairs vol. 19, no. 2, 1995, p. 65.

Despite the limited scholarly support for secondary sanctions, public officials continue to consider them a viable—and, at times, effective—foreign policy tool.18The idea of secondary sanctions varies across the decades and scholarly disciplines, and research findings apply to a range of efforts, not all conforming to the definition of secondary sanctions presented in this brief. A good example are the claims made by President Obama, Secretary Hillary Clinton, and several foreign policy experts regarding Iran’s agreement to negotiate establishing limits on its nuclear-enrichment program. In September 2014, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani agreed to conduct international negotiations, with the intended outcome of a curtailed and inspected Iranian nuclear program, in exchange for the relaxation, and ultimate elimination, of US- and UN-mandated economic sanctions. The negotiation culminated in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed by Iran, China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, and the European Union in July 2015.19The international nuclear agreement was forged in 2015 and agreed to by Iran and six other countries—the United States, UK, Russia, France, China, and Germany.

What role did secondary sanctions play in this diplomatic breakthrough? Based on a review of analyses and assessments of the conditions and events that led to the agreement, an aggressive US diplomatic offensive was instrumental in securing and implementing secondary sanctions that targeted banks and other companies doing business with Iran.20Kenneth Katzman, “Iran Sanctions,” Congressional Research Service, February 21, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/RS20871.pdf; Meghan L. O’Sullivan, “Iran and the Great Sanctions Debate,” Washington Quarterly vol. 33, no. 4, 2010, pp. 7–21, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/Iran%20and%20the%20Great%20Sanctions%20Debate.pdf; Matthew Levitt, “The Implications of Sanctions Relief Under the Iran Agreement,” testimony submitted to the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, August 5, 2015, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/testimony/LevittTestimony20150805.pdf. These secondary sanctions were deemed the key factor persuading Iran to negotiate an agreement to limit its nuclear program, including international inspection, and the sanctions were most consequential from 2010–2014. A significant amount of business between other countries and Iran was halted by the imposition of US sanctions against increasingly broader categories of commercial transactions. As the United States gradually expanded those categories, through both legislation and executive orders, “foreign companies and governments wound down their investments in Iran’s energy sector, halted financial transactions with designated Iranian banks, and, eventually, reduced their oil purchases from Iran and withheld Iranian [funds] in their domestic banks. Those secondary sanctions were effective, not only because of the threat of restrictions on access to the US market for foreign companies doing covered business with Iran, but also because of the acceptance of those threats by foreign governments which gave their companies no cover. Indeed, many of these countries, especially in Europe, followed the US measures with outright prohibitions on the activities themselves.”21David Mortlock, What Does the President’s Decision on Iran Mean for Iran Sanctions? Not Much, Yet (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2017),http://www.publications.atlanticcouncil.org/decision-iran-sanctions/.

As with all economic sanctions, firms and individuals pay a price when secondary sanctions are deployed. When secondary sanctions are deemed effective, the commercial losses by firms and individuals in the sanctioning, sanctioned, and targeted countries may be easily judged as necessary, part of the cost of achieving the foreign policy goal. In addition, firms and individuals conducting business with the sanctioned regime might be considered to have ill-gotten gains—at least from the perspective of the sanctioning country. When the effect of secondary sanctions is uncertain, an economic hardship occurs—often for innocents—to no purpose. It is a disruption in business practices and relationships that can be difficult to re-establish, even after the economic sanctions regime has ended. Secondary sanctions should not be cast as merely a prop to give the appearance of taking meaningful actions against an ally or adversary.

For example, the Trump administration has invoked secondary sanctions as a diplomatic goad to intensify Chinese enforcement of UN-approved economic sanctions. However, a recent report found that forty-nine nations have been undertaking trade and investment with North Korea, violating UN Security Council sanctions. Given the lax enforcement of the primary sanctions already adopted, the effects of secondary sanctions on North Korea are likely to be very limited. Expanding the number of secondary sanctions on China, to a level where the effects may be felt by North Korea, may also exceed China’s tolerance for interference in its own economy—challenging its sovereignty, and risking the instigation of new conflicts with China.

Despite the overwhelming research that finds secondary sanctions largely ineffective, they are likely to remain a popular foreign policy tool. Governments that invoke secondary sanctions have a self-serving interest in claiming their success (just as sanctioned countries have for dismissing their importance), muddying assessments of their true effects. Also, secondary sanctions are a very public way to demonstrate a re-energized commitment to achieving the sanctioning country’s foreign policy goals. The controversy over the effectiveness of secondary sanctions is unlikely to be resolved in a definitive way, and the merits of their past and future deployment will be judged on a case-by-case basis.

Strategic use of secondary sanctions

Appreciating the differences between multilateral, extraterritorial, and secondary sanctions is fundamental to designing and implementing well-aligned economic sanctions. Each of these modalities has important implications for the approach used to engage other countries, and to gain support in the sanctioning country. The most effective approach will depend on any given country’s relationship with the sanctioned country, its interest in achieving the goal associated with sanctions, and its ability to retaliate against the sanctioned country. The effectiveness of secondary economic sanctions should be judged no differently than that of any other form of sanctions. They can be effective when designed to achieve the intended economic consequences, given the vulnerabilities of the sanctioned country.

The sanctioning country may choose secondary sanctions for practical reasons. It may have exhausted all of its options for imposing sanctions unilaterally, while believing that greater economic losses for the sanctioned country are still necessary. Secondary sanctions can be used to pressure firms and individuals outside the sanctioning country to withdraw commercial activities from another country, even though their own country’s laws do not require them to do so. In addition, the sanctioning country might choose to substitute secondary sanctions for unilateral sanctions, and thereby avoid economic losses to its own economy that would be incurred by adopting economic sanctions.

However, the real risks associated with secondary sanctions might outweigh their potential benefits. Unlike traditional economic sanctions, secondary sanctions carry the risk of retaliation by the country or countries where they apply. For example, secondary sanctions imposed by the United States against Chinese firms and individuals are intended to limit commercial transactions between China and North Korea, and to further depress North Korea’s economy. But, might not China find a way to retaliate against the United States for the sanctions imposed on its own companies and citizens?

In practice, the distinction between different sanction modalities is not brightly demarcated. For example, US laws authorizing economic sanctions typically allow for a broad set of executive actions. Such an expansive mandate allows the United States discretion in the actions it may take—against not only the sanctioned country, but others as well. The specific scope and scale of economic sanctions often change over time. Given this approach, legislation authorizing economic sanctions gives the United States all the legal justification it needs to adopt secondary sanctions against firms and individuals, at its own discretion.

The strategic use of secondary sanctions presents a paradox. When used in a limited manner—involving only a few firms and/or individuals, and in reaction to evolving events—prospects are poor that they will play an influential role in influencing another country’s enthusiasm for economic sanctions. But, because the effects are minimal, the secondary sanctions are unlikely to incur any retribution of note. Alternatively, the greater the use of secondary sanctions—expanding the economic losses and opportunities felt by the targeted firms and individuals—the more likely that the countries involved will retaliate. And, if a country targeted by secondary sanctions is largely powerless to retaliate, then traditional diplomatic pressures from the sanctioning country (without secondary sanctions) would suffice.

Supporters of economic sanctions should be expected to believe in the righteousness of their expectations for a change in policy by the sanctioned country, but it is unreasonable to expect other countries to automatically endorse these expectations. Under the right circumstances, secondary sanctions could be an effective means for pressuring other countries to support economic sanctions, but such circumstances are uncommon. Without confidence in their efficacy, imposing secondary sanctions on firms and individuals resident in other countries—allies and adversaries alike—will likely result in unnecessary suffering by those living in the sanctioned, sanctioning, and target countries, with little or nothing to show for it.

The experience of secondary sanctions’ use in service of intensifying economic sanctions against Iran provides useful guidance on some of the specific conditions whereby secondary sanctions could be a useful foreign policy tool.

The experience of secondary sanctions invoked against entities and individuals suggests a singular set of circumstances when secondary sanctions could be useful:

- The sanctioning country controls a vital and singular commercial asset not available elsewhere in the global economy.

- The sanctioned entity can deny access to this commercial asset, with limited prospects for replacement.

- Denied access results in immediate and tangible economic losses, or certain losses in the near term.

- The resulting economic losses for the sanctioned entity are significant and permanent.

- Target countries comprise a comprehensive and multilateral force.

- The sanctioned country’s policy in dispute is viewed as a significant international problem by the international community.

In the case of Iran, the combined and comprehensive efforts of the United States and EU to deny banks that did business with Iran access to the Western banking system, in essence, denied Iran access to global banking services, with devastating consequences for its economy. Successful secondary sanctions strongly suggest the need for a multilateral sanctions regime.

Conclusion

Secondary sanctions extend a sanctioning country’s capacity to cause economic harm in the sanctioned country. But, they do add risk by introducing the possibility of incurring conflicts with allies or adversaries. Secondary sanctions should be considered an option when designing economic sanctions, but only under a very particular set of circumstances. Therefore, secondary sanctions have limited practical applications. As with any economic sanction, if deployed incorrectly, they can do more harm than good.