Spotlight: Alejandro Giammattei’s first 100 days

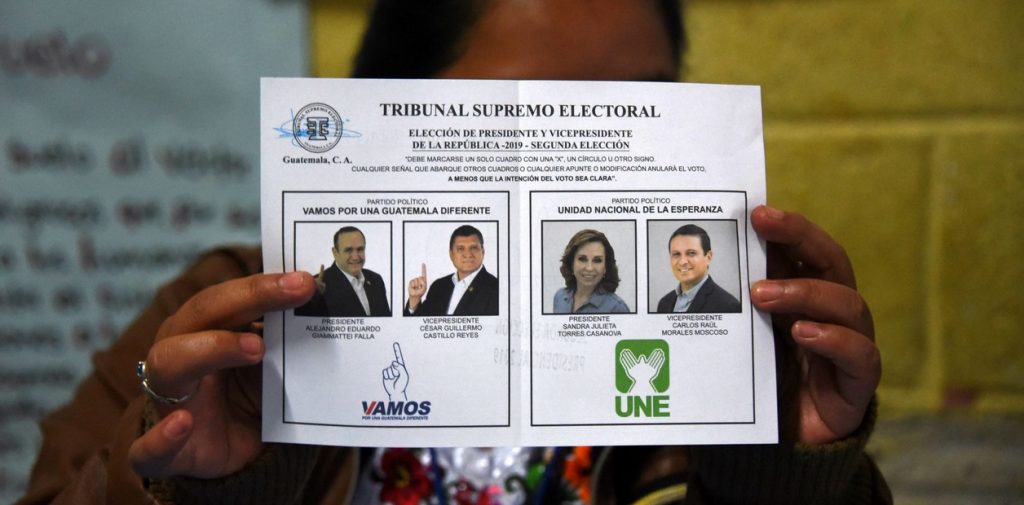

President-elect Alejandro Giammattei Falla, former director of the Guatemalan penitentiary system, will take office on January 14, 2020, having defeated Sandra Torres in a runoff election. The task ahead for incoming President of Guatemala Giammattei is not an easy one. Multi-ethnic Guatemala is the largest economy and the most populous country in Central America, and it is still recovering from more than three decades of civil war that ended twenty-five years ago. Guatemala is also one of the most unequal and poorest nations in Latin America: up to two thirds of the population lives on less than $2 per day. In the Western Highlands, three of four people live below the poverty line.

In the past, food and citizen insecurity, combined with a lack of economic opportunities, have pushed out many Guatemalans. In 2018, nearly one third of apprehended migrants at the US border were Guatemalans, and most of the apprehended family units came from Guatemala. The effects of climate change—mostly manifested through droughts and crop failure—add another challenge for improving Guatemala’s economic trajectory. From day one, Giammattei will have to forge alliances in Congress. With only seventeen of one hundred and sixty seats, Giammattei’s VAMOS party controls only a little over 10 percent of Congress.

Boosting economic growth and creating job opportunities

At the center of President-elect Giammattei’s campaign is the promise to usher in a new era of economic growth and job creation. With 59 percent of its population living in poverty, Guatemala’s lack of economic opportunities has forced millions to seek better futures elsewhere. But, the high numbers of migrants have given renewed momentum for Giammattei to double down on boosting the economy with a multi-pronged plan that includes domestic-focused policies, foreign investment, and regional collaboration.

Coming from the private sector, Giammattei’s economic slogan is to rely on the “market as much as possible and the on State as much as needed,” according to his government platform Plan Nacional de Innovación y Desarrollo (PLANID). He intends to apply this neoliberal approach to four sectors that he hopes will drive economic growth, investment, and employment: exports, infrastructure, MSMEs (micro, small, and medium enterprises), and tourism.

It will be crucial for Guatemala to tackle its institutional and security challenges in tandem with any new economic plans.

Giammattei sees immense opportunity for Guatemala to expand exports and cross-border economic collaboration with Mexico. Guatemalan exports to Mexico totaled $509 million in 2017, while exports to the United States totaled $4.2 billion. In a recent forum with the Mexico-Guatemala Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CAMEX), Giammattei outlined a series of prospective projects in the border region, in cooperation with Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Some of these projects include: building a cross-border “Maya Train”; creating a free-trade zone around the Guatemala-Mexico border; deregulating aerial and ground transport to reduce costs around movement of people; promoting public-private partnerships; and facilitating commerce.

Another key project with Mexico is to create a “regional binational development bank,” which would be part of a broader strategy for Guatemala to benefit more from its geographical position bordering the North American trade bloc, while taking a leadership role in strengthening intraregional trade in Central America. A major focus of the bank would be the northern departments of Huehuetenango and San Marcos, the points of departure for the vast majority of Guatemalan migrants trekking north.

On tourism, Giammattei proposed handing over the management of the Mundo Maya airport to the Flores municipality in Petén. The goal of this concession, which emulates the situation of the privately run Punta Cana airport in the Dominican Republic, is to promote a competitive airport that attracts airlines and tourists to Guatemala’s Mayan heritage and biosphere.

Per PLANID, underpinning Giammattei’s economic plan is a promise to improve educational quality, attract private-sector investment, and promote entrepreneurship by loosening regulations and streamlining processes for starting a business. With the proper conditions in place, Giammattei aims to reach $5 billion annually in foreign direct investment.

In his first one hundred days in office, it will be crucial for Guatemala to tackle its institutional and security challenges in tandem with any new economic plans. Addressing structural issues around corruption, crime, poor infrastructure, and inefficient government bureaucracy will take as much political will and investment as the Giammattei administration can muster. An important measure of Giammattei’s economic policies will be his ability to reduce irregular migration by creating employment opportunities that provide a viable reason for Guatemalans to stay in their country. To achieve the “free market economy with social justice” that he seeks, President-elect Giammattei must boost inclusive economic development by investing not only in key industries, but also in human capital and workforce training, as a way to empower underprivileged Guatemalans and sustain growth over the long term.

Combating corruption without the CICIG

As former director of the Guatemalan prison system (2006-2008), President-elect Giammattei is no stranger to Guatemala’s law-and-justice sphere. Giammattei recognizes that high levels of corruption have eroded citizens’ trust in the political class. Likewise, he acknowledges Guatemala’s poor performance in international rule-of-law, governance, and perception-of-corruption indexes directly affects business, investment, and citizen security in his country.

Guatemala’s contemporary fight against corruption dates back to 2006, when President Oscar Berger and the United Nations “finalized terms for the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala–CICIG).” The CICIG began working in 2007 and, three years later, President-elect Giammattei was at the center of the commission’s first major case. The case revolved around extrajudicial executions at El Pavón prison while he was its director; Giammattei was acquitted at trial. Twelve years later, in September 2019, President Jimmy Morales allowed CICIG’s mandate to expire, despite strong citizen support for the commission—in 2019, more than 70 percent of citizens had a favorable view of the body. Like outgoing President Morales, Giammattei is a vocal opponent of the CICIG, but acknowledges that Guatemala needs help from allies (namely the United States and Israel) to fight corruption.

Giammattei has promised to create a special commission linked to the executive branch. The government will finance the commission with up to $10,000 per year obtained from restructuring of existing institutions. The remaining expenses, the government hopes, will come from international organizations and other countries.

Giammattei is also betting on using technology to improve governance and citizens’ access to information. A first step will be to make government transactions available online, in an attempt to increase the state’s transparency and accountability. For the private sector, high levels of corruption in procurement are a barrier to investment. The key lies in undertaking structural reforms that “improve efficiencies while preserving transparency.”

Balancing priorities in US-Guatemala ties and China’s increasing role in the Northern Triangle

President-elect Giammattei’s foreign policies will be highly anticipated by the international community. Per PLANID, US-Guatemala relations are of utmost priority because of the impact of remittances—which are closely linked to migration—on his country. Integration of the Central American region—which Giammattei recently discussed in a visit to Israel—and building relationships with key global economic players are also top foreign policy priorities.

An expected early step from Giammattei is to renegotiate the US-Guatemala migration deal, which he believes is not “right for the country”—a feeling 80 percent of Guatemalans share.

US-Guatemala ties are strong, but not perfect. Migration is at the heart of the US-Guatemala bond. In this respect, an expected early step from Giammattei is to renegotiate the US-Guatemala migration deal, which he believes is not “right for the country”—a feeling 80 percent of Guatemalans share. Giammattei will also request expansion of temporary protected status (TPS) in the United States to Guatemalans, so they can work without fear and send remittances home. Remittances, which US President Donald Trump threatened to tax if Guatemala did not enter into a migration agreement, added up to 12.1 percent of Guatemala’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018, mostly from Guatemalans in the United States. Per PLANID, the incoming administration plans to create a jobs program with micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to reintegrate deported Guatemalans into society and reduce the chance that they will try to migrate again. To further strengthen ties with the US, Giammattei intends to open more embassies and consulates. Doing so will also allow Guatemala to prioritize the human rights and fair treatment of Guatemalan migrants in the United States.

Another affair to watch during Giammattei’s first one hundred days: China. While keeping diplomatic ties with Taiwan, Giammmattei will reinforce and strengthen commercial ties with China. He will take office just a month after China announced major projects and investment in neighboring El Salvador. It is yet to be determined how this will affect Guatemala’s ties with China, Taiwan, and the United States.

Finally, Giammattei will actively engage with his neighbors and work toward an ambitious intraregional economic bloc, which would include free transit of merchandise and people in Central America. An annual investment fair to showcase Central America is an objective. Similar to MERCOSUR, the Central American trade bloc will strive to negotiate trade deals as one, with the goal of negotiating better results and opportunities for Central America.

Reducing insecurity for an investment-ready Guatemala

Violence and insecurity have seen a downward trend in Guatemala. In 2018, the country had a homicide rate of 22.4 per one hundred thousand inhabitants, the lowest since the end of the civil war in 1996. While still a high number globally, it is the lowest among Northern Triangle countries, and lower than rates in Colombia, Brazil, and Mexico. However, Guatemala still ranks among thirteen countries with the worst criminality indexes in the world and has an impunity rate averaging 94 percent since 2008. With the termination of the CICIG, tackling the country’s top public-safety concerns will require additional resources, technical expertise, and a set of comprehensive policies.

Despite his controversial two-year stint heading Guatemala’s prisons, President-elect Giammattei nevertheless touted his security credentials during the campaign to position himself as the candidate better equipped to combat crime in Guatemala. His ten-month arrest—and the following acquittal—were especially important in shaping his views on prison and justice reform. He has suggested reforms to pre-trial detention, such as house arrest and more use of fetters for tracking detainees. He also identifies overcrowded and dangerous prisons as perpetuating the vicious cycle of crime, and proposes organizing prisoners by the level of risk they carry.

Giammettei’s policy proposals on citizen and national security provide less insight into specific steps his administration will take, but point to the broader vision of his campaign: that fostering a business-friendly climate will lead to a more prosperous Guatemala. According to PLANID, the strategic objective of his security plan is to “improve the country’s governability for a coexistence in harmony and peace that allows for investment and employment.” This is why he has made it a priority to combat extortion, which has increased by 55 percent in five years (2013-2018). Extortion payments made by victims—in many cases, owners of small businesses—account for 2 percent of the country’s GDP.

Other proposals in this plan, which include a mix of crime control and prevention, are: increasing state presence and control in rural territories, to both protect private property and preserve indigenous lands; devising new conflict-resolution mechanisms and long-term prevention programs for at-risk youth; strengthening penal and justice institutions (Organismo Judicial, Ministerio Público, Defensa Pública Penal, INACIF, Sistema Penitenciario); and restructuring, modernizing, and professionalizing security forces. While Giammettei has expressed doubts in the past about the effectiveness of police militarization, it is yet unclear how he will reorganize the distribution and responsibilities of the police (Policía Nacional Civil) versus the armed forces (Fuerzas Armadas).

Notably, drug trafficking—a major issue for Guatemala, which is a key geographic transit point hosting hidden landing strips scattered across dense forests—is not mentioned by name in his security proposals. PLANID instead states the president-elect’s intention to work with regional partners to tackle this transnational issue, given that Guatemala is “not the cause of the problem, but simply a route of the problem.”

When Giammattei assumes office in January, his administration will be the first in thirteen years to enact security and justice reforms without the CICIG. He will need to strike a delicate balance between preventive programs that tackle the root of security issues in Guatemala, while implementing short-term policies that enhance governability in gang-ridden areas and rural territories. In his attempt to create the investment climate that comes with a more secure society, Giammattei will need to be careful not to resort to mano dura policies that have been proven counterproductive across the region.

Conclusion

President-elect Giammattei will face a challenging road ahead in terms of driving economic growth, rooting out corruption, reducing insecurity, and strengthening Guatemala’s relations with its regional neighbors and the world. His first one hundred days will be vital in providing clarity of direction for these policy priorities. How inclusive will his economic growth be? With the CICIG gone, will he be able to tackle corruption and impunity without appearing to politicize the justice system? If the Giammattei administration is open to negotiate and compromise with the opposition-dominated Congress and effectively leverages regional political alignment with Mexico and Northern Triangle neighbors, the path forward for Guatemala could exceed expectations for millions of Guatemalans who deserve a better future in their own country.