Strengthening financial inclusion in the Caribbean: Treating correspondent banking relationships as a public good

Table of contents

Introduction

What drives financial de-risking in the Caribbean?

Why correspondent banking relationships are a public good

Policy recommendations

Benefits for the Caribbean and its partners

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

About the author

Introduction

Economic development and prosperity in Caribbean countries1Countries covered in this publication include Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. require a stable and secure financial sector. The ability to access international finance and credit, trade with other countries, and secure foreign investment are all actions that underpin this stability, especially for the small and open markets in the Caribbean. Vital to performing these actions are correspondent banking relationships, which financial institutions, governments, and citizens use to conduct cross-border financial transactions. Correspondent banking relationships are a public good, given how crucial they are to the proper functioning of economies and financial systems, especially for small countries in the Caribbean.

However, over the past decade, Caribbean countries have seen a significant withdrawal of these relationships (also known as financial de-risking), which is when a financial institution severs, rejects, or puts limits on transactions with a particular group and/or individual customer. The Caribbean is frequently cited as the region of the world most affected by this phenomenon.2“De-risking in the Financial Sector,” World Bank, October 7, 2016, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialsector/brief/de-risking-in-the-financial-sector

Stabilizing correspondent banking relationships in the Caribbean requires imparting on the international financial system an appropriate and equitable understanding of the challenges small markets face from financial de-risking, and the important role they play in the health of the global economy. One way to achieve this is to conceptualize and categorize correspondent banking relationships as a type of critical financial market infrastructure (CFMI), which would help highlight the fact that if the financial sectors of one region (in this case, the Caribbean) are significantly affected by financial de-risking, the economic consequences could be felt globally. Global governments, regulators, and central banks work to ensure CFMIs’ viability and sustainability since financial systems and economies would find it difficult to function without them.3“Principles for Financial Market Infrastructure,” Bank for International Settlements, n.d., https://www.bis.org/cpmi/info_pfmi.htm, accessed August 1, 2023

This issue brief builds on the 2022 Atlantic Council report Financial De-risking in the Caribbean: The US Implications and What Needs to Be Done,4Jason Marczak and Wazim Mowla, Financial De-risking in the Caribbean: What Needs to Be Done and US Implications, Atlantic Council, March 1, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/financial-de-risking-in-the-caribbean/ which was produced after a series of roundtables held among members of the Financial Inclusion Task Force (FITF) organized by the Atlantic Council’s Caribbean Initiative. In that first report, the FITF explained that categorizing correspondent banking relationships as CFMI “would provide global recognition to the importance that correspondent banking services provide to the health and ability for growth of Caribbean economies and citizens.”5Ibid. In 2023, the Caribbean Initiative convened several members of the FITF along with other financial experts to provide a practical and actionable recommendation to US, Caribbean, and multilateral stakeholders on the necessity of categorizing correspondent banking relationships as CFMI.

What drives financial de-risking in the Caribbean?

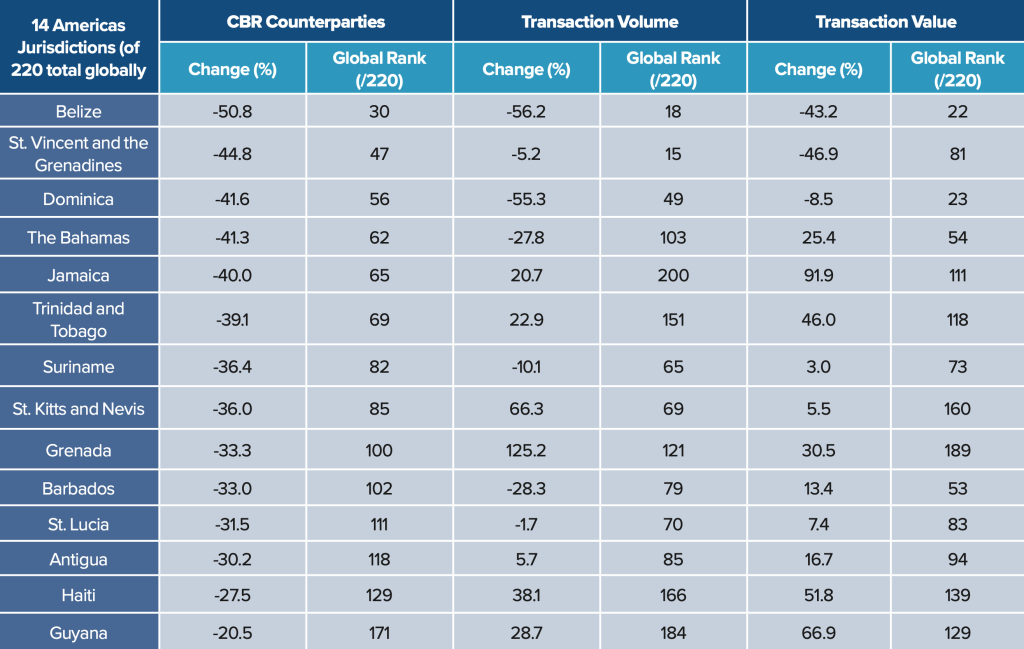

There are two main drivers of financial de-risking in the Caribbean: 1) limited profitability for correspondent banks due to the relatively small size and volume of transactions; and 2) countries’ classification as “high-risk jurisdictions,” and their perceived weak regulatory frameworks to address money laundering and terrorism financing. Both drivers have contributed to a broad decline in correspondent banking relationships.6“The FinCEN Files—a Caribbean Perspective,” Caribbean Association of Banks, October 8, 2020, https://cab-inc.com/the-fincen-files-a-caribbean-perspective/ The Caribbean Association of Banks survey in 2017 noted that twenty-one of its twenty-three member countries had lost at least one correspondent banking relationship. Further, an analysis of Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) data (contained in our 2022 report) confirmed these lost correspondent banking relationships, with some countries faring worse than others, such as Belize, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Dominica, The Bahamas, and Jamaica, which all saw a more than 40 percent reduction in correspondent banking relationship counterparties between 2011 and 2020.7 Marczak and Mowla, Financial De-risking in the Caribbean

It is worth noting that while all Caribbean countries analyzed for this report saw a reduction in correspondent banking relationships over the period, not all saw a reduction in transaction volumes or values. However, in all cases, fewer correspondents saw an increase in the concentration of flows through fewer counterparties, which ultimately increases potential risks. Should the consolidation trend continue, this means entire financial systems will become more reliant on fewer institutions, increasing the possible impact on the system should more banks decide to cease doing business in or with the region.

Table 1. Change in correspondent banking relationships, transaction volumes, and transaction values across Caribbean countries, 2011-2020

Profitability limits identified by correspondent banks are based on a risk versus reward calculus. First, correspondent banking is a fee-based service, and given the small populations of Caribbean countries, there are inherently small volumes of transactions occurring between correspondent and respondent banks. As a result, correspondent banks weigh those potential profits against stringent US regulations that threaten heavy fines and sanctions if a Caribbean financial institution that has a relationship with a US correspondent bank is unable to mitigate risks, such as financial crimes. In many cases, the risk of the relationship with the Caribbean counterparty outweighs the potential reward.

Factoring into the perceived risks of engaging with Caribbean jurisdictions are concerns from US banks about the region’s ability to manage and mitigate illicit finance. Correspondent banks perceive that despite increased capacity to adhere to anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) standards, Caribbean governments have weak regulatory frameworks that do not sufficiently address concerns over financial crimes. Further, many Caribbean countries that face financial de-risking are continually classified by the US Department of State’s annual International Narcotics Control Strategy Report as jurisdictions with high rates of money laundering and drug trafficking. The report is one of the factors correspondent banks account for when determining whether to maintain or begin a correspondent banking relationship in the Caribbean. During the 2022 financial de-risking roundtable held in Barbados and co-chaired by then-Chair of the House Financial Services Committee Maxine Waters and Prime Minister of Barbados Mia Mottley, several Caribbean heads of government shared that their ministries lack the capacity to provide sufficient responses to the report’s contents. For US correspondent banks, particularly mid-tier ones, this poses a significant challenge as they fear inheriting the reputational risk of Caribbean jurisdictions, which influences their own relationships with correspondent banks at home.

Financial de-risking and its drivers have many possible economic implications for Caribbean countries, impacting a wide range of stakeholders, including governments, financial institutions, and citizens. The potential impact on remittances is one example. In this case, financial de-risking and lost correspondent banking relationships increase costs and risks for money transfer operators (companies moving currencies from one financial institution to the other). Citizens themselves, particularly those most vulnerable and dependent on remittances for subsistence, bear the brunt of this burden. As an example, Jamaica—where remittances are equal to a fifth of overall gross domestic product—has placed limits on the amount of money that can be transferred due to a stricter regulatory regime. Outside of remittances, financial de-risking can limit access to international capital needed to facilitate investment, trade, and access to credit—all critical for commerce and development, especially in the Caribbean.

Why correspondent banking relationships are a public good

The economic and investment activity that correspondent banking relationships support makes them a crucial public good. Essentially, public goods are those that benefit all citizens by providing positive outcomes for individuals and institutions. Most often, governments play an important role in ensuring access to public goods. The same should be true for correspondent banking relationships, and both Caribbean governments and their advanced economy partners have a role to play in protecting them. Of course, this does not obviate the need for appropriately sound and rigorous regulatory frameworks, which must continue to be enforced and bolstered to mitigate money laundering and terrorism financing concerns. These two objectives can certainly reinforce one another.

This is precisely the reason why the SWIFT payments system is deemed a critical financial market infrastructure. SWIFT is an intermediary and executor of financial transactions among banks globally, including sending payment orders that are then settled by correspondent accounts among financial institutions.8Ibid. As of 2018, half of all high-value cross-border payments used SWIFT payments in more than two hundred countries and territories.9 Ibid. The effects of restricted access to the SWIFT network—and by implication, correspondent banking—was evident in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where multiple Russian banks’ access was limited. This was a form of economic sanction, which led to significant operating delays and increased financial costs for counterparties across the globe. Although an extreme example, this highlights the importance of correspondent banking flows and related risks that restricted access to correspondent banking flows implies, which are particularly acute for small open economies such as those of the Caribbean.

Policy recommendations

Categorizing correspondent banking relationships as CFMI or a public good can help underscore their importance to long-term economic development for Caribbean economies and catalyze resources and reforms needed to address related challenges. While more work is needed to comprehensively diagnose capacity, institutional deficits, and policy reforms—for both regional and correspondent bank host countries—the following preliminary options would support progress in this effort and are discussed below.

First, the members of the House Financial Services Committee should consider taking action that encourages the US Treasury and MDBs to redouble efforts to provide technical assistance and capacity building aimed at improving regulation, supervision, and reporting requirements for Caribbean financial institutions. As discussed, driving financial de-risking in the Caribbean are the perceived reputational risks for banks due to increasingly strenuous AML/CFT regulations and compliance standards. MDBs and other development partners have provided support to individual countries, but this can be scaled and regionalized to facilitate dialogue and needs assessments, maximize resources and effectiveness, and avoid duplication of efforts. The potential benefits of such an initiative would extend well beyond the issue of financial de-risking and support financial sector stability, development, and inclusion more broadly. Streamlined assistance that is underpinned by legitimate institutions such as MDBs and the US Treasury can help instill confidence in correspondent banks, bringing new relationships to the region or protecting those that already exist.

Second, the House Financial Services Committee could work with the US Treasury and MDBs to create a regional facility with a mandate to provide services to customers and jurisdictions where costs and risks are challenging for conventional financial institutions. Modalities should include bundling smaller transactions to generate greater economies of scale and providing financial incentives that would help address challenges posed by the increasing costs of counterparty risk assessments. The facility could also serve as a bridge of information among governments, regulatory bodies, and MDBs to help fill information gaps and ensure that financial institutions are in the best position to keep up with rapidly evolving international compliance standards.

Benefits for the Caribbean and its partners

US and MDB support for categorizing correspondent banking relationships as CFMI would benefit broader Caribbean economic development goals. Steady access to correspondent banking relationships creates and maintains a strong financial sector. This helps encourage local banks to lend to the local private sector, thus stimulating economic growth among micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises—the backbone of Caribbean economies. This is even more important since the Caribbean is import-dependent on petroleum products, medical services and equipment, food supplies, and foreign investment to build infrastructure projects such as roads and critical facilities. While the region is making strides to reduce import dependence, the nature of its open and small economies ensures that there will always be some reliance on the global financial system. For example, given the accumulating effects of climate change in the region, climate and development finance from MDBs and organizations such as the Green Climate Fund will be essential to adaptation and mitigation efforts. However, these groups are unlikely to lend in local currencies and, even if they do, the goods needed to purchase equipment and services will primarily come from abroad and require payment in the form of international currencies.

But the United States and MDBs also benefit from correspondent banking relationships categorized as CFMI. In recent years, the United States and MDBs have used their global platforms to advocate for Caribbean priorities. Some reform has come of this, such as debt pauses announced by MDBs and new policy frameworks such as PACC 2030, but little has been done in the area of financial de-risking. Addressing this issue through a first step with CFMI categorization would help build additional goodwill and help MDBs support their own development agendas in the Caribbean and other Small Island Developing States. Financial de-risking is not just a Caribbean problem with other countries such as those on the African continent affected as well. Therefore, both the United States and MDBs have an opportunity to address a significant development challenge at a global level.

Conclusion

Correspondent banking relationships are crucial conduits for foreign exchange and finance, which are the lifeblood of Caribbean economies. Given the importance of correspondent banking relationships, they fit the criteria first as a public good, and second as CFMI. This categorization is not just important, but feasible and justifiable. It is in the interest of all actors to maintain a functioning and healthy global system and categorizing correspondent banking relationships as CFMI is the first step to ensuring that all countries and citizens have access to it.

Acknowledgments

At the Atlantic Council, we thank board member and founder of the Caribbean Initiative Melanie Chen for her support of this publication and our previous work on financial de-risking. We would also like to thank the experts and policymakers who joined the private roundtables and one-on-one consultations that informed this publication, including Nigel Baptiste, Henry Mooney, Wendy Delmar, Dawne Spicer, Stephen Thomas, and Deepa Sinha. A special thank you goes to Jason Marczak, senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, for his guidance, leadership, and comments during this publication’s process and to Charlene Aguilera for her help and support in coordinating this publication.

About the author

Wazim Mowla is the associate director of the Caribbean Initiative at the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. He leads the development and execution of the initiative’s programming, including the Financial Inclusion Task Force, the US-Caribbean Consultative Group, the PACC 2030 Working Group, and the Caribbean Energy Working Group. Since joining the Atlantic Council, Mowla has co-authored major publications on the strategic importance of sending US COVID-19 vaccines to the Caribbean, strategies to address financial de-risking, and how the United States can advance new policies to support climate and energy resilience. As part of his work on the Caribbean, Mowla was called to provide congressional testimony to the US House Financial Services Committee on financial de-risking. Mowla holds bachelor’s degrees in international relations and history and a master’s degree in public history from Florida International University, and a master’s degree in comparative regional studies from American University.

Related content

The Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center broadens understanding of regional transformations and delivers constructive, results-oriented solutions to inform how the public and private sectors can advance hemispheric prosperity.

Image: A woman receives Bolivar notes from an automated teller machine (ATM) in Caracas, Venezuela March 23, 2018. REUTERS/Marco Bello