Syria’s energy sector and its impact on stability and regional developments

A quick outlook regarding Syria’s energy resources and infrastructure, including the role of declining oil revenue under the Assad regime’s governance and the prospects for, and geopolitical impact of, Syrian energy production and trade in a new era.

Executive summary

Syria has the potential to significantly increase its oil and natural gas production, which can provide energy and government revenue that are critical for its stability and reconstruction. Syria was an oil exporter in the decades prior to its civil war, and its natural gas production started to increase on the eve of the war. Most of Syria’s oil and natural gas fields are located in eastern Syria, in areas that are currently largely under the control of the predominately Kurdish Peoples’ Protection Units (YPG) and where US forces are deployed. The YPG is an affiliate of the terrorist-designated Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) but has been a partner of the United States in its campaign against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS). Control of these oil and natural gas fields plays a role in the developing conflict between the new central government and the YPG, and will potentially serve as an issue of disagreement between Washington and Ankara. In the future, Syria will likely be integrated into regional natural gas trade and might become a transit state for Israeli and Egyptian gas heading to Turkey and to Europe. Turkey announced its intention to begin exclusive economic zone (EEZ) delimitation negotiations with Syria. This will likely spark opposition from Cyprus and Greece, which might turn to Washington and Brussels for support.

1. Syria’s energy resources and infrastructure

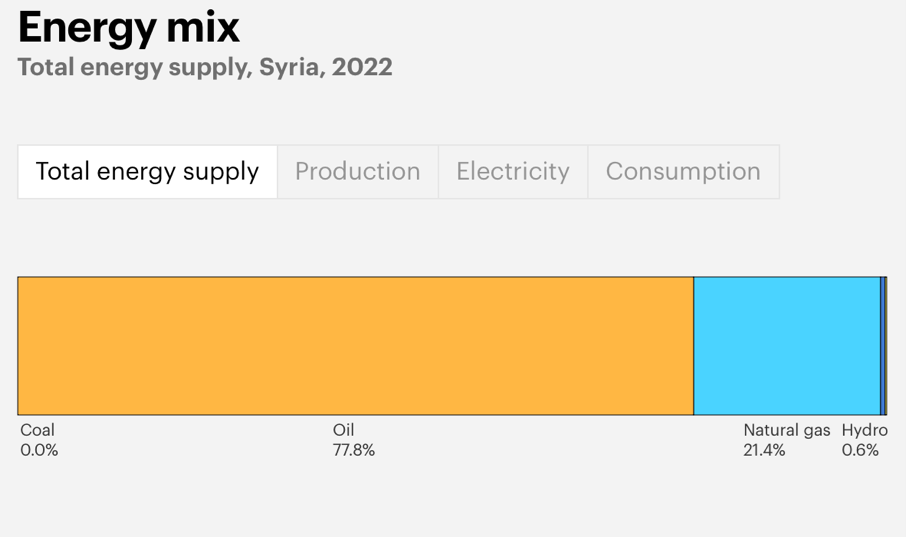

Prior to the outbreak of Syria’s civil war in 2011, the country’s oil and natural gas reserves meant it was self-sufficient in terms of energy supplies. Before the civil war, Damascus also exported oil. Sales of oil and gas provided 20 percent of the government’s revenue.1“Syria Overview,” US Energy Information Administration, last updated June 24, 2015, https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/country/syr.

Most of Syria’s oil and natural gas fields are located in the eastern part of the country. As of publication, the YPG controlled the bulk of the fields in northeast Syria. Control of these fields is a major factor in the new regime’s efforts to establish its full authority in Syria. The new central government aims to gain control of these fields, and this plays a role in the unfolding conflict between it and the YPG, as well as disagreements between Turkey and the United States.

Foreign actors are already increasing their involvement in Syria via the energy sector. Qatar and Saudi Arabia have pledged to supply fuel to Syria.2Benoit Faucon and Summer Said, “Arab States Race Turkey for Influence in New Syria,” Wall Street Journal, January 10, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/world/middle-east/arab-states-race-turkey-for-influence-in-new-syria-cb33670b.

Turkish companies such as TPAO and BOTAŞ are positioned to play a leading role in future oil and gas exploration and production in Syria, while Turkish power companies will likely play a major role in Syria’s electricity sector. Azerbaijan will also likely play a role in developing the Syrian energy sector.3“CEO: SOCAR Türkiye Poised to Aid Syria’s Post-Conflict Energy Needs,” Caliber, January 6, 2025, https://caliber.az/en/post/ceo-socar-turkiye-poised-to-aid-syria-s-post-conflict-energy-needs. Azerbaijan has already sent significant aid to Syria, including fuel supplies. Due to its close alliance with Turkey, Azerbaijan will likely work together with the Turkish government and Turkish energy companies in energy provision and development in Syria. In addition, foreign companies such as Total and Shell, which operated in Syria before the civil war, will have an advantage in gaining access to Syrian exploration and production.4“How Has the Fall of Assad Impacted Syria’s Energy Sector?” Reuters, December 9, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/how-has-fall-assad-impacted-syrias-energy-sector-2024-12-09/.

2. Oil

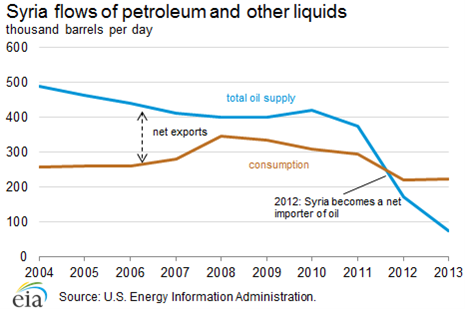

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimated in 2015 that Syria possessed 2.5 billion barrels of proved oil reserves.5“Syria Overview.” Syria’s crude is heavy and sour.6Ibid. In 2010, Syria produced 383,000 barrels per day of oil.7Ibid.

Estimates of Syria’s oil output on the eve of Bashar al-Assad’s ouster range between 40,000–80,000 barrels per day.8Ibid.; Tom Pepper, “Will Syria’s Oil Sector Be Revived?” Energy Intelligence, December 12, 2024, https://www.energyintel.com/00000193-bb07-dcf4-ab9b-fbaf4fb50000. Up until Assad’s departure, Iran was providing the bulk of Syria’s oil supplies, up to 100,000 barrels a day. Tehran supplied this oil to Syria essentially for free, via a credit line that Damascus did not pay. Iran stopped supplying oil to Syria on December 9, 2024.9“How Has the Fall of Assad Impacted Syria’s Energy Sector?” Iran has told the new regime in Syria that it owes Iran between $30–50 billion for these fuel supplies and other aid during the Assad period.10“Reopening Embassy in Syria Depends on Security Guarantees, Iran Says,” Iran International, December 17, 2024, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202412175122; Abhishek G. Bhaya, “Why Is Iran Asking for $30 Billion from Syria?” TRT World, December 24, 2024, https://www.trtworld.com/middle-east/why-is-iran-asking-for-dollar30-billion-from-syria-18246663. According to press reports, the new government in Syria does not intend to pay these Assad-era debts. Instead, it responded that Iran owes Syria $300 billion for the damage its forces did there.11“Syria to Target Iran with $300 Billion Compensation Demand—Lebanese Outlet,” Iran International, December 25, 2024, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202412254184.

3. Oil refineries

Syria has two oil refineries, located in Homs and Banias, and both are state owned. Before the war, these refineries’ capacity met Syria’s refined product demand.12“Syria Overview.” However, the refineries suffered extensive damage during the civil war.

4. Natural gas

In 2015, the EIA estimated Syria’s natural gas reserves at 240 billion cubic meters (BCM). Syria possesses both wet and dry gas.

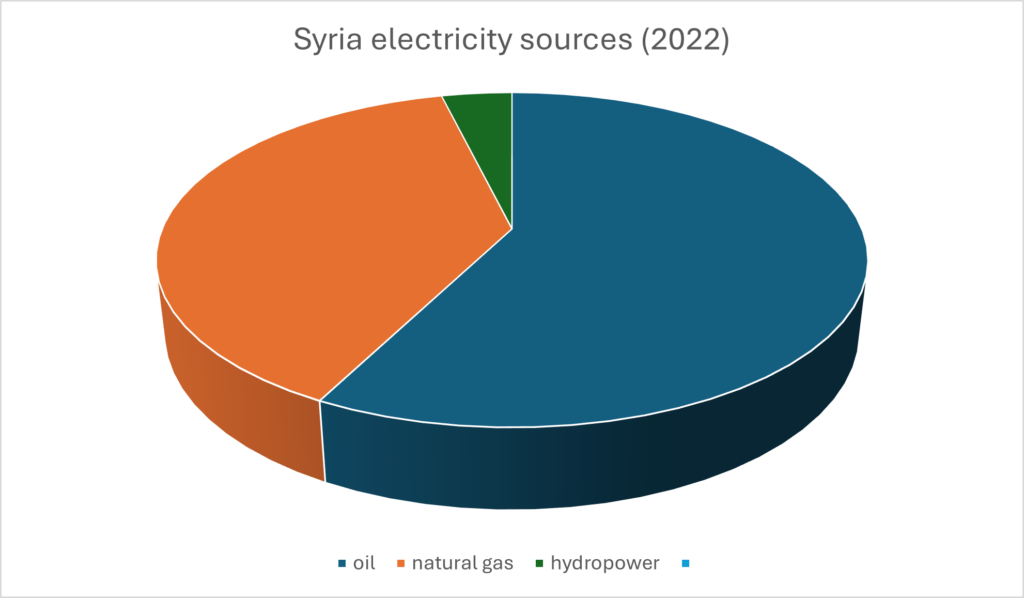

Syria’s natural gas is used for power production and is needed for reinjection into Syria’s oil fields. According to BP, Syria produced 8.7 BCM of natural gas in 2011, which fell to 3 BCM annually by the 2024 fall of the Assad regime.13“How Has the Fall of Assad Impacted Syria’s Energy Sector?” According to IEA estimates, natural gas provided one-quarter of Syria’s electricity supplies in 2022.14“Syria: Oil,” US Energy Information Administration, last visited January 13, 2025, https://www.iea.org/countries/syria/oil.

Syria has not explored for oil and natural gas in its EEZ, though legal preparations to commence exploration were under way prior to the war. Like its neighbors in the Eastern Mediterranean, Syria is likely to discover oil and gas resources in its EEZ.

Prior to the war, several foreign companies engaged in natural gas development in Syria, including Canada’s Suncor Energy, the United Kingdom -based energy group GulfSands Petroleum, and China’s Sinochem. In addition to its oil production, Total also developed the Tabiyeh natural gas project. Damascus contracted the Russian energy holding Soyuzneftegaz to explore in Syria’s EEZ, but exploration didn’t commence.

5. Electricity

Provision of electricity to the public is one of the new Syrian government’s most important tasks to establish its rule and attain stability. Syria’s leader Ahmed al-Sharaa has stated a goal of providing eight hours per day of power by late February.15John Irish and Alexander Ratz, “EU Could Lift Some Syria Sanctions Quickly, France Says,” Reuters, January 8, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/eu-could-lift-some-syria-sanctions-quickly-france-says-2025-01-08/.

Ankara has pledged to support Syria through restoration of electricity supplies to the public. Turkey has already extended electricity supply in Syria: the Idlib region receives power from Turkey, and Ankara is extending its reach to repair power plants in Syria. Turkey’s Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Alparslan Bayraktar stated that in the first phase, “[Turkey] must bring electricity to the places in Syria where there is no electricity very quickly. We will do this here first with imports. With medium-term plans, we are planning to increase the electricity installed capacity and the production capacity there.”16“We Will Bring Syria Together with Energy,” Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, December 27, 2024, https://enerji.gov.tr/news-detail?id=21424.

Turkey and Qatar have committed to deploy floating power-supply vessels to provide electricity to Syria.17“Syria to Receive Electricity-Generating Ships from Qatar and Turkey,” Reuters, January 7, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/syria-receive-electricity-generating-ships-qatar-turkey-2025-01-07/. Turkey has deployed a fleet of such vessels in various countries, including in Africa.

Prior to the outbreak of the civil war, Syria generated close to 29.5 billion kilowatt hours of electricity annually, while its consumption was 25.7 billion kilowatts.18“Overview: Syria.” The bulk of this came from thermal power plants fueled by oil and natural gas. The Tishrin hydropower plant in the Aleppo district provided 4 percent of Syria’s electricity.

6. From exporter to importer

In almost textbook manner, the civil war broke out just as Syria’s growing oil consumption became equal to its declining production. Thus the regime had dwindling financial means to sustain its power and provide public goods, coopt support, and pay the security services. The revenue drop from oil sales was a major factor in the regime’s inability to cope with public unrest and, thus, its decision to rely on support from Iran, Russia, and Hezbollah.

During the Arab Spring, governments in regional countries rich in oil and gas survived the challenge, supported by government subsidies to the public for energy and other goods. However, states like Egypt that went from energy exporters to energy importers, and states like Syria with dwindling oil production rates, were not able to mitigate the effects of rising fuel and foods costs through increasing subsidies because they no longer had significant revenues from energy exports.19For more on the impact of decreased oil revenue and regime stability, see: Brenda Shaffer, “A Guide to the Application of Energy Data for Intelligence Analysis,” Studies in Intelligence 61, 7 (2017), https://www.cia.gov/resources/csi/static/Application-of-Energy-Data.pdf.

7. Future developments

Syria has significant potential to increase its oil and natural gas volumes. Syria can also serve as a transit state for natural gas from Israel and other producers in the Eastern Mediterranean to Turkey and onward to Europe. Turkey will play a major role in Syria’s reemerging energy sector. US, UK, and EU sanctions waivers and exemptions for World Bank loans are necessary to facilitate the investment for energy supplies in Syria. The World Bank has ended loans for fossil fuels projects, and an exemption will be necessary to allow public finance for Syria’s energy sector.

Turkey will likely lead the reconstruction of Syria, especially in the field of energy.20Gokhan Ergocun, “Türkiye Ready to Repair, Rebuild Infrastructure in War-Torn Syria, Says Minister,” Anadolu English, December 24, 2024, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/turkiye-ready-to-repair-rebuild-infrastructure-in-war-torn-syria-says-minister/3433287. Ankara plans to help develop Syria’s oil and natural gas resources and use energy exports to fund reconstruction. As Bayraktar explained, “We aim to develop these projects . . . we are acting with a vision to bring this potential of Syria to the Syrian economy and to use the resources obtained from there for the development, construction and development of Syria.”21“We Will Bring Syria Together with Energy.” He stated that Syria’s oil production can increase significantly and the oil can be sent to Turkey’s refineries. The minister stated that Turkey will work with the new government in Syria on an infrastructure masterplan.22Ibid.

Improvement of Syria’s electricity supplies can benefit Lebanon, which also suffers from insufficient power supplies. Bayraktar said Turkey could also send electricity to Lebanon via Syria.23Ibid. Future natural gas supplies from Syria or transited via Syria could also be supplied to Lebanon, which could greatly improve Lebanon’s economic prospects.

As developments unfold, the control of Syria’s oil and gas fields and power plants will change hands. As pointed out above, most of the oil and gas fields are located in areas controlled by the YPG and in proximity to US forces, which are partners of the Kurdish militia. Thus, the status of the oil and gas fields is intertwined with Damascus’s efforts to disband the YPG as well as the developing understanding between Turkey and the United States regarding Syria. The new regime in Damascus, together with Turkey, will challenge and likely prevail over the YPG and other Kurdish militias.

Discord between the new regime in Syria, Turkey, and the United States over the status of the Kurdish militias in Syria is likely to change with the departure of the Joe Biden administration. The Donald Trump administration will likely withdraw the US forces, albeit probably several months after entering the White House.

Syria will likely be integrated into regional gas trade and, as noted earlier, might serve as a transit state for gas exports from Israel and Egypt to Turkey and Europe. While this may sound farfetched, it is not without precedent. During 2021–2022, Biden’s energy coordinator, Amos Hochstein, led efforts to establish Egyptian gas exports via Jordan, along the Arab Gas Pipeline, to Syria and onward to Lebanon. Lebanon and Syria signed gas import agreements with Egypt while, in parallel, Egypt agreed to import additional Israeli gas volumes via Jordan.24Timour Azhari, “Lebanon, Syria, Egypt Sign Gas Import Agreement,” Reuters, June 21, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/lebanon-syria-egypt-sign-gas-import-agreement-2022-06-21/; “Eastern Mediterranean,” US Energy Information Administration, November 16, 2022, https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/regions-of-interest/Eastern_Mediterranean; Stuart Elliott, “Israel Approves New Route for Gas Exports to Egypt via Jordan,” S&P Global, February 17, 2022, https://www.spglobal.com/commodity-insights/en/news-research/latest-news/natural-gas/021722-israel-approves-new-route-for-gas-exports-to-egypt-via-jordan. Essentially, increased volumes from Israel would have enabled Egyptian exports to Syria and Lebanon, and Israeli gas would have been supplied to Syria and Lebanon. All the participants in the plan were aware of the reality that Egypt would be supplying Israeli gas to Syria and Lebanon.

Export of Israeli gas and/or electricity to Syria—perhaps under the Egyptian or Jordanian label—could provide quick relief for Syria’s energy shortages. However, the lack of direct relations between Syria and Israel, and the currently poor state of relations between Ankara and Jerusalem, prevents this. Despite the harsh rhetorical exchanges between Israel and Turkey in recent weeks, the two countries share interests in Syria: stability, prevention of the country being used as a springboard for terrorism, and removal of Iranian militias and influence.

If stability is reached in Syria, Damascus will likely succeed in increasing its natural gas production and might be able to export gas to markets such as Lebanon and Turkey. Prior to the civil war, Egypt led efforts to extend the Arab Gas Pipeline to the Turkish border. A pipeline connection on land or a pipeline via Syria’s EEZ to Turkey would not require major investments.

Turkish officials announced that Ankara would like to quickly delimitate its maritime EEZ border with Syria in order to initiate oil and gas exploration.25Tuncay Sahin, “Türkiye Eyes Maritime Agreement, Infrastructure Revival in Syria,” TRT World, December 24, 2024, https://www.trtworld.com/turkiye/turkiye-eyes-maritime-agreement-infrastructure-revival-in-syria-18246911. The borders set between Syria and Turkey will likely pose a challenge to the declared EEZ of Cyprus. Thus, the Syrian-Turkish EEZ decision could trigger reaction from Cyprus and Greece, which could appeal to Brussels and Washington to take action.26“Cyprus Irked at Turkey’s Activities in Syria,” Famagusta Gazette, December 28, 2024, https://famagusta-gazette.com/cyprus-irked-at-turkeys-activities-in-syria/.

Finance for energy projects in Syria will require the removal—or at least the waiver—of US, EU, and UK sanctions that were imposed on Syria under the Assad regime. The United States has already declared a waiver of its sanctions for six months to facilitate humanitarian supplies to Syria, including fuel.27“U.S. Treasury Issues Additional Sanctions Relief for Syrian People,” US Department of Treasury, press release, January 6, 2025, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2770; “Syria Sanctions,” US Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control, last visited January 13, 2025, https://ofac.treasury.gov/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/syria-sanctions. The Trump administration is likely to support the removal of the sanctions on Syria. The president can grant waivers, even if the congressional sanctions are not removed. The actions of the new regime in Syria, and of Turkey in Syria, will affect congressional approval of sanctions removal.

An exemption from the World Bank and Group of Seven (G7) countries’ limitations on funding of fossil fuel projects would also be needed in order to access public finance to support the rebuilding of Syria’s energy infrastructure and production. The Trump administration is expected to remove the limitations on public finance for fossil fuels, which were adopted during the Biden administration. The Trump administration will likely advise the World Bank to remove the limitations as well. However, this could take time, while Syria will need loans to reestablish energy supplies quickly.

To summarize, this paper recommends the following action:

- The U.S. should support a process that leads to Syria’s oil and gas fields returning to central government control.

- Unlock World Bank and regional public bank financing for fossil fuel projects in Syria.

- Remove Western sanctions or grant waivers to allow investment and trade with Syria.

- Washington should work with Ankara to integrate Syria into regional electricity and natural gas trade.

Energy will play a major role in the developing events in Syria in the coming months. The new government’s ability to provide electricity and fuel will strongly affect public support and is necessary to jump-start the economy. Foreign engagement in Syria will focus heavily on the energy sector. Turkey will rebuild electricity supplies, while Saudi Arabia and Qatar will likely pay for the replacement of the free Iranian fuel supplies that Tehran had provided to Syria. Further along, Syria might play a role in regional natural gas trade.

About the author

Professor Brenda Shaffer is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center, a faculty member at the US Naval Postgraduate School and Advisor for Energy at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Follow her on X @ProfBShaffer.

The Atlantic Council in Turkey aims to promote and strengthen transatlantic engagement with the region by providing a high-level forum and pursuing programming to address the most important issues on energy, economics, security, and defense.

Related content

Image: A view shows electricity pylons in Kiswah, Damascus suburbs, Syria September 8, 2021. Picture taken September 8, 2021. REUTERS/Yamam al Shaar