JUST IN

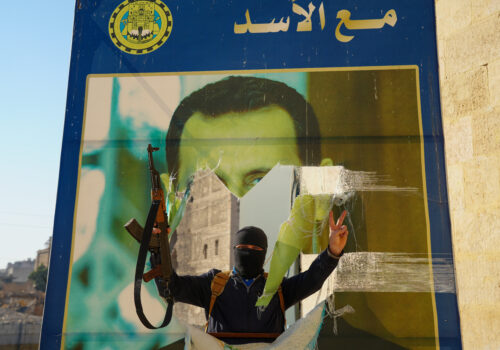

The butcher has left the building. On Sunday, Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad fled the country as rebel groups took over Damascus, in a stunning turn of events in Syria’s devastating thirteen-year civil war. The power shift in Syria will reverberate across the Middle East and the world, from Russia and Iran to Turkey and the United States. Our experts are here to explain all the implications.

TODAY’S EXPERT REACTION BROUGHT TO YOU BY

- Rich Outzen (@RichOutzen): Nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Turkey Program, former US State Department official, and former US Army foreign area officer

- Qutaiba Idlbi (@Qidlbi): Senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs, where he leads the Syria portfolio

- Kirsten Fontenrose: Nonresident senior fellow in the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs and former US National Security Council senior director for the Gulf

- Jonathan Panikoff (@jpanikoff): Director of the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and former US deputy national intelligence officer for the Near East

What Syrians are thinking

- Celebrations across Syria reflect the bottom line: “The long suffering of the Syrian people under a brutal regime that killed, tortured, dispossessed, and exiled millions of its people has ended,” Rich tells us.

- The United States can step in to help prevent chaos, Qutaiba argues. The Biden administration should surge funding immediately to “rebuild infrastructure, provide healthcare, and support the momentum for a quick return of refugees and displaced persons.”

What HTS is thinking

- The Syrian rebel group that led the offensive, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which is listed as a terrorist organization by the United States, has earned a seat at the table of transition talks, Kirsten tells us. But there are dangers to HTS-led governance. “Statements from HTS about respecting minorities should not be interpreted as a sign of moderation in the group’s ideology,” she cautions, adding that “the Taliban made similar ‘campaign trail’ promises to protect women’s rights and minorities in order to smooth their way into power, then flagrantly betrayed them.”

- Noting that US President-elect Donald Trump has asserted that the United States should not get involved in the conflict in Syria, Kirsten, who served in the first Trump administration, tells us that “the only way for the [Syrian] opposition to gain advocacy from the next US administration is to quickly present a pragmatic and unified plan for a transitional government, elections, and ongoing governance.”

- An important factor will be how the international community uses its newfound leverage. “No entity, including HTS, will be able to effectively run the country without near-total dependence on foreign aid,” Kirsten says. Yet “this is the point in post-conflict scenarios where donors usually muck things up” by pursuing divergent reconstruction plans, empowering competing political actors, funding duplicative projects, and not tying funding to specific milestones.

What regional powers are thinking

- “Iran and Russia have suffered a dramatic loss of influence in Syria and the region as a result of wars in the Middle East and Ukraine,” Rich says. The two powers were capable of coming to Assad’s rescue in 2014-15, but it was “impossible” for them to do so now, he points out.

- For the Gulf states, the reaction to Assad’s ouster will be conflicted, Jonathan tells us from Doha. Qatar “might be more inclined to provide financial resources for whatever government emerges in Damascus,” he says, but the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have “long-standing concerns” about Islamist governments and “a reluctance simply to give away free money, as opposed to investing in countries.” That could lead the latter two countries to wait and see what leadership emerges in Syria.

- Israel, too, is likely to have mixed feelings, Jonathan explains, given the uncertainty about who will follow Assad. Still, Israel in recent months weakened Lebanon-based Hezbollah, a key backer of Assad, to the point that “Syrian opposition forces felt confident they could take advantage.” Israel, Jonathan reasons, may now want to leverage the development to privately negotiate with Syria’s emerging leaders to ensure security in the north.

- “Turkey is the only country that seems to have had a winning strategy for Syria,” says Rich. It opposed Assad while negotiating with his backers, hosted refugees, and supported the opposition politically and militarily. Ankara, Rich adds, now has “unrivaled leverage” over the stabilization and rebuilding process, and the goodwill of many Syrians.

- Stabilization, Qutaiba notes, will require the United States to engage Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Israel, and Jordan in talks. “Encouraging dialogue between adversarial states,” he argues, could “help reduce tensions and foster cooperative security arrangements.”

Further reading

Sun, Dec 8, 2024

Experts react: Rebels have toppled the Assad regime. What’s next for Syria, the Middle East, and the world?

New Atlanticist By

Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad has been ousted as opposition forces quickly took the Syrian capital. Atlantic Council experts share their insights on the developments.

Thu, Dec 5, 2024

What does Turkey gain from the rebel offensive in Syria?

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

The rebel offensive took many by surprise, but analysts familiar with the situation in Syria were aware that the rebels were prepared to launch it by mid-October.

Tue, Oct 8, 2024

A bipartisan Iran strategy for the next US administration—and the next two decades

Report By

As tensions spike in the Middle East, how should the next US president approach Iran and its network of proxies including Hezbollah and Hamas? With a strategy that can be maintained for decades, by administrations of either party. A bipartisan, expert working group lays out the details.

Image: Women use their mobile phones near a damaged picture of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad as people celebrate, after Syrian rebels announced that they have ousted President Bashar al-Assad, in Qamishli, Syria December 8, 2024. REUTERS/Orhan Qereman