The Maduro Regime’s Illicit Activities: A Threat to Democracy in Venezuela and Security in Latin America

Key Points

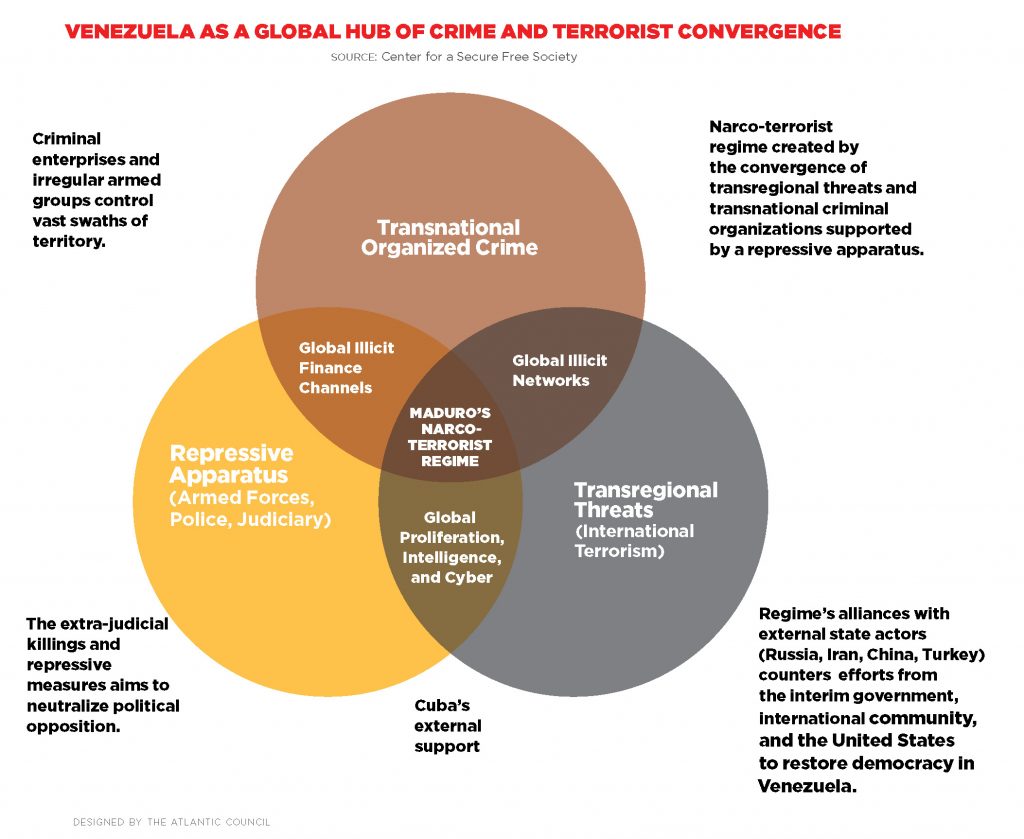

- Nicolás Maduro’s global web of illicit activities provides a lifeline of support to his regime and impedes a restoration of democratic stability in Venezuela.

- Though the Maduro regime's partners of choice include authoritarian states such as Russia and Iran, the criminal network has also reached actors in democracies in Western Europe.

- Disrupting Maduro's criminality will require sustained pressure and the close collaboration of international partners, especially among the United States, Europe, and Venezuela's neighbors.

Introduction

By Diego Area and Domingo Sadurní

Two months after the internationally recognized interim government marked its first year, Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis, the worst ever in the Western Hemisphere’s modern history, entered a new phase. The coronavirus pandemic, which has rattled even the most developed nations, is further straining a crippled health system already unable to provide even the most basic medicines, stalling an economy in never-ending hyperinflationary collapse, and fueling social unrest as food and gasoline become increasingly scarce.1Fabiola Zerpa, James Attwood, and Nicolle Yapur, “Venezuela on Brink of Famine with Fuel Too Scarce to Sow Crops,” Bloomberg, June 11, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-11/venezuela-on-brink-of-famine-with-fuel-too-scarce-to-sow-crops. Nicolás Maduro has taken advantage of this crisis to further restrict political liberties and stifle any political dissent.

The pandemic has also disrupted migrant and refugee flows. Still, worsening conditions inside the country will inevitably force even more Venezuelans to seek better lives elsewhere, at the same time that regional neighbors struggle with their own public resources already pushed to the brink. The reverberations of a growing migration crisis—the world’s largest outside of war—will place increasing strains on fragile institutions across the region already reeling from the shocks of coronavirus.

The need for a political resolution to the Venezuela crisis is more urgent than ever. In June 2020, following a humanitarian agreement with the interim government, the regime-controlled Supreme Court appointed new officials to the national electoral body for this year’s legislative elections in a move to shore up regime control of the vote. Opposition figures are under increasing attack, while the regime is focused on creating divisions to erode the unity of democratic forces.

The Maduro regime remains entrenched. Its cronies control Venezuela’s electoral council, and two illegally formed judicial and legislative bodies rule at its direction. Importantly for this paper, the regime also controls an international web of criminal activities providing financial lifelines of support. That is why democratic forces in Venezuela, in coordination with regional and international allies, must engage new courses of action to disrupt and deter the illicit funding sources and the nefarious external and non-state partners that help sustain Maduro and his backers. Reining in the influence of malign regional and global actors, especially their roles in regime-supported narcotrafficking, illegal gold mining, and money-laundering operations will be critical to advancing democratic stability in Venezuela.

This policy brief provides critical insight into some of the Maduro regime’s illicit activities impeding a recovery of democratic institutions in Venezuela. It examines the origins of the regime’s criminal enterprises, how the regime leverages economic and political ties with regional and international states to advance its illicit networks, and the criminal partnerships with Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) dissidents and National Liberation Army (ELN) in drug and gold mining operations. It also focuses on the role of Europe—a unique and powerful partner of democratic forces in Venezuela, but also a place where illicit funds originating from the regime flow through its banks and financial system. With that, how should international allies of the interim government respond?

The Joint Criminal Enterprise that Maduro Inherited

With his 1998 election as president of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez initiated a regional movement known as the Bolivarian Revolution, using his nation’s oil wealth to inaugurate his “Socialism for the 21st Century” political project. The project was aimed at creating an ideologically linked alliance of state and non-state actors to remake Latin America’s political landscape and diminish US influence in favor of extra-regional actors such as Russia, Iran, and China. As Chávez systematically consolidated power, he transformed Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA)—the Venezuelan national oil company—into a multi-billion-dollar enterprise that provided oil and financial resources to his allies. Over the years, this social and political network would morph into the Bolivarian Joint Criminal Enterprise (BJCE)—an alliance of state and non-state actors that operates in concert with sympathetic political leaders, economic elites, and criminal organizations.2Name coined by the author. More about the BJCE here: Douglas Farah and Caitlyn Yates, “Maduro’s Last Stand,” IBI Consultants, LLC, and National Defense University, May 2019, https://www.ibiconsultants.net/_pdf/maduros-last-stand-final-publication-version.pdf It was led first by Chávez, and now by the Nicolás Maduro regime.

While Chávez led the project, he was aided by an array of allies. Regionally, Chávez, with Cuban advisers, used PDVSA funds to back the successful electoral campaigns of like-minded leaders in Nicaragua, Bolivia, Ecuador, Suriname, and El Salvador beginning in the mid-2000s, forming the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA).3In 2010, several communications were sent to Washington, DC, from the US embassy in Nicaragua, revealing financial ties between Hugo Chávez and Daniel Ortega. The US ambassador identified a scheme in which top Nicaraguan officials received cash and gifts from Venezuela, as well as funds to finance the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) party. “EE UU: Chávez y el Narcotráfico Financian la Nicaragua de Ortega,” El País, December 6, 2010, https://elpais.com/internacional/2010/12/06/actualidad/1291590036_850215.html; “Chavez Funding Turmoil across Bolivia,” Guardian, January 24, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/jan/24/venezuela.colombia; In 2008, Interpol certified that there was evidence of financial links between Hugo Chávez´s administration, FARC, and the campaign of then-candidate Rafael Correa. “Interpol Confirma la Relación de Chavez y Ecuador con las FARC,” El País, May 15, 2008, https://elpais.com/internacional/2008/05/15/actualidad/1210802418_850215.html; Along with accusations of funding Desi Bouterse´s election, Chávez created a regional scheme to provide subsidized oil for countries in the Caribbean and Central America, creating an official mechanism to provide support to his political allies in the region. “Chavez Encabezará Petrocaribe,” BBC, December 21, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/spanish/business/newsid_7155000/7155145.stm; According to El País, US intelligence reports show Hugo Chávez´s strategy to fund Frente Farabundo Martí. “Washington Asegura que Chávez Financiará a la Izquierda Salvadoreña,” El País, February 6, 2008, https://elpais.com/internacional/2008/02/07/actualidad/1202338808_850215.html; Joel D. Hirst, “A Guide to ALBA,” Americas Quarterly, https://www.americasquarterly.org/a-guide-to-alba/. The BJCE also extended extra-regionally, with Venezuela and its allies primarily engaging actors in Iran, Russia, China, and, to a lesser extent, Syria and North Korea.

For over a decade, Chávez maintained close diplomatic and economic relations with Iran. Venezuela saw an opportunity to advance its anti-US agenda and Iran sought to expand its influence in Latin America via Caracas. For example, with support from the Chávez administration, Iran established eleven new embassies in the region from 2005–2009 and provided funding for a Bolivarian military training academy in Bolivia.4Roger F. Noriega, et al., “Kingpins and Corruption: Targeting Transnational Organized Crime in the Americas,” American Enterprise Institute, June 26, 2017, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/kingpins-and-corruption-targeting-transnational-organized-crime-in-the-americas/. While Iran-Venezuela relations dwindled after Chávez’s death in 2013, Maduro has recently sought closer ties to Tehran—which is also facing strong sanctions from the international community. Earlier this year, Iran—defying US sanctions—shipped gasoline to fuel-starved Venezuela in exchange for gold.5Stephen Johnson, “Iran Is Working Hard to Revive Anti-U.S. Operations in Latin America, June 1, 2020,” https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/01/iran-venezuela-alliances-latin-america/.

Russia has been Venezuela’s most important military, economic, and political ally under both Chávez and Maduro. During the last decade and a half, Venezuela purchased $11 billion in weapons from Russia (only India purchased more from Moscow), including tanks, advanced fighter jets and anti-ballistic missile systems.6Douglas Farah and Kathryn Babineau, “Extra-regional Actors in Latin America: The United States is not the Only Game in Town,” PRISM Journal of Complex Operations, National Defense University, February 26, 2019, https://cco.ndu.edu/News/Article/1767399/extra-regional-actors-in-latin-america-the-united-states-is-not-the-only-game-i/. Russia has provided a lifeline to Maduro by purchasing Venezuelan oil and offering key diplomatic support at the United Nations. Regionally, Moscow is increasingly a regional spoiler seeking to undermine US legitimacy in Latin America. Meanwhile, China has become the primary financial enabler of Venezuela, providing tens of billions of dollars in loans and direct foreign investment, often in extractive industries like oil and mining.7Ibid. As of 2018, Beijing’s investments in Venezuela totaled $67 billion, comprising more than 40 percent of China’s investment in the region.8Kevin P. Gallagher and Margaret Myers, “China-Latin America Finance Database,” Data as of 2019, https://www.thedialogue.org/map_list/.

With high oil prices and an abundance of crude reserves, Chávez used PDVSA as an avenue to not only build his alliance, but also to consolidate power and launder money through his alliance with other states in the BJCE.9For more information regarding the influence Chávez created in the Caribbean through Petro Caribe and Alba see Asa K. Cusack, “Protests, Polarization, and Instability in Venezuela: Why Should the Caribbean Care?” Caribbean Journal of International Relations & Diplomacy 2, 1, March 2014, 99–111, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1477139/1/459-974-1-SM.pdf; For a full discussion of criminalized states, see Douglas Farah, Transnational Organized Crime, Terrorism, and Criminalized States in Latin America: An Emerging Tier-One National Security Priority (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2012), http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=1117. Using PDVSA as the primary laundering vehicle, Chávez (and later Maduro) moved money through PDVSA coffers using programs like “oil exchanges,” fictitious massive infrastructure projects, front companies, and sophisticated offshore financial structures to not only siphon off money from the oil company, but also to launder billions of dollars in illicit proceeds from the sales of cocaine, gold, and other commodities.

While the extent of the criminal endeavors led first by Chávez and now by Maduro are not entirely known, reasonable estimates of parts of the expansive enterprise have come into focus. A 2019 investigation by Connectas, a Latin American consortium of investigative journalists, estimated that Venezuelan officials siphoned off $28 billion from PDVSA under the Petrocaribe program that Chávez began in 2005.10Investigación #Petrofraude, “El descalabro continental chavista con dinero de los venezolanos,” Connectas, https://www.connectas.org/especiales/petrofraude/. IBI Consultants traced at least $10 billion in Venezuelan funds that moved through PDVSA’s criminal network, operated by Central American allies in Nicaragua (Albanisa) and El Salvador (Alba Petróleos), from 2007 to 2018.11Douglas Farah, “Convergence in Criminalized States: The New Paradigm” in Beyond Convergence: World Without Order (Washington, DC: Center for Complex Operations, National Defense University Press, 2016), https://cco.ndu.edu/Portals/96/Documents/books/Beyond%20Convergence/BCWWO%20Chap%208.pdf?ver=2016-10-25-125402-247. Based on ongoing review of legal cases and investigations, the total amount of illicit revenues that moved through PDVSA structures is likely to be closer to $40 billion through 2018.12Farah and Yates, “Maduro’s Last Stand.”

Some of the illicit funds moving through the PDVSA structure were generated from cocaine sales by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), with whom Chávez built a close alliance beginning in the 1990s, at a time when the group was the largest producer of cocaine in the world and a designated terrorist organization by the United States and European Union. While the FARC and the government of Colombia signed a peace agreement in December 2016, dozens of senior FARC commanders and several thousand combatants have rejected the agreement and declared themselves “dissidents.” These dissidents, along with Colombia’s National Liberation Army (ELN), now operate primarily out of Venezuelan territory under the protection of the Maduro regime.13Venezuela Investigative Unit, “FARC Dissidents and the ELN Turn Venezuela into Criminal Enclave,” InSight Crime, December 10, 2018, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/farc-dissidents-eln-turn-venezuela-criminal-enclave/.

Under Maduro, the criminal element of the regime, in coordination with the FARC and the BJCE, has grown as oil prices have fallen and Venezuela’s production has plummeted, hitting a 76-year low in May 2020.14Marianna Parraga, “Venezuela’s oil exports sank in June to 77-year low: data,” Reuters, July 1, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-oil-exports/venezuelas-oil-exports-sank-in-june-to-77-year-low-data-idUSKBN2427AC. This internationally diversified portfolio includes illicit gold mining, drug trafficking, money laundering, weapons trafficking, and massive corruption. While these relationships have been reported in recent years, two key events in 2020 established a public record of the Maduro regime’s criminal alliances. The first was the indictment by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) of senior Venezuelan government officials, including Maduro, unsealed in March 2020, which described the criminal partnership between the Maduro regime and the FARC to move tons of cocaine under state protection to international markets. The second was the June Interpol capture of Colombian-Venezuelan businessman Alex Saab, the Maduro regime’s front man, which publicly highlighted the flurry of illicit schemes paid for by public funds, and the international actors who allegedly aided and abetted such operations.15United States of America v. Nicolas Maduro Moros, 1:11-CR-205 (S.D. N.Y. 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/page/file/1261806/download; @Armando.Info, “A propósito de las versiones sobre la posible detención de Alex Saab, aquí rescatamos algunas de nuestras investigaciones que revelan parte de los negocios de quien en los últimos años se convirtió en el principal contratista y sostén financiero de Nicolás Maduro,” Twitter, June 12, 2020, 10:49 p.m., https://twitter.com/ArmandoInfo/status/1271650768458788864.

Taken together, the investigative reporting, indictments, and US Treasury Department of asset forfeiture and designation actions clearly document how the Maduro regime’s adaptable, multifaceted illicit network provides much-needed financial and political support, enabling Maduro, and his cronies and allies, to steal billions of dollars for personal gain and regime survival, at the expense of the Venezuelan people.

A Venezuela-Colombia Guerrilla Partnership: Drug Trafficking, Illicit Mining, and More

As outlined in the March DOJ indictment of Maduro et al., as well as dozens of preceding indictments, Maduro regime officials operating under the criminal military-based structure known as the Cartel de los Soles (referring to insignias of high-ranking military officials in the Venezuelan armed forces) have a robust symbiotic relationship with dissident members of the FARC, including its top commanders, Iván Marquez and Jesús Santrich.16“Nicolás Maduro Moros and 14 Current and Former Venezuelan Officials Charged with Narco-Terrorism, Corruption, Drug Trafficking, and Other Criminal Charges,” US Department of Justice, press release, March 26, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/nicol-s-maduro-moros-and-14-current-and-former-venezuelan-officials-charged-narco-terrorism. The cartel allows FARC-produced cocaine to move through Venezuela in exchange for cash and services used to win cartel loyalty. In return, the regime offers the FARC a safe haven in Venezuelan territory, weapons, and secure cocaine-transportation routes.17Ibid.

The 2008 killing of senior FARC commander Raúl Reyes in Ecuador, and the subsequent recovery of six hundred gigabytes of internal FARC documents, showed the deep web of connections among the FARC, Chávez, and Chávez’s regional allies at the time, including leaders in El Salvador, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Bolivia.18“Colombian Farc rebels’ links to Venezuela detailed,” BBC News, May 10, 2011, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-13343810. This included evidence of the direct involvement of Chávez and senior Venezuelan intelligence and military officials in the cocaine trade, and the use of FARC money to fund electoral campaigns in the region. For example, multiple investigations have shown how the Banco Corporativo in Nicaragua and the joint Venezuelan-Russian Evrofinance Mosnarbank—both shut down following US sanctions—as well as a host of small banks across Central America and the Caribbean, have been vital to moving illicit funds, including funds generated from illicit mining operations.19“Treasury Targets Finances of Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega’s Regime,” US Department of Treasury, press release, April 17, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm662; “Treasury Sanctions Russia-based Bank Attempting to Circumvent U.S. Sanctions on Venezuela,” US Department of Treasury, press release, March 11, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm622.

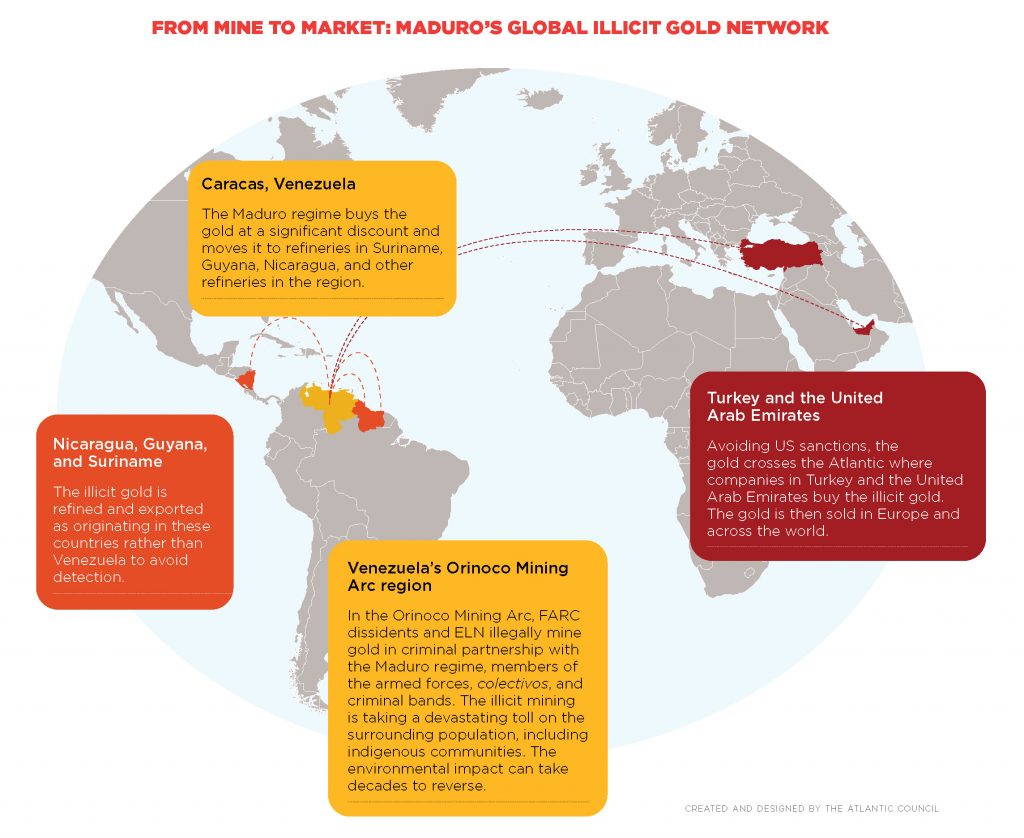

The armed groups and the regime have a complex scheme in which the former operate the mines and the latter sells the minerals through state-owned companies.

The Maduro regime has also offered safe haven for the ELN, which controls much of the illicit gold mining in Venezuela and Colombia—the fastest-growing criminal economy in the region.20James Bargent and Cat Rainsford, “Game Changers 2019: Illegal Mining, Latin America’s Go-to Criminal Economy,” InSight Crime, January 20, 2020, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/gamechangers-2019-illegal-mining-criminal-economy/. The ELN, as well as the FARC, serves the dual purpose of providing funds to the Maduro regime while also helping the regime retain territorial control in remote, but strategically vital, areas bordering Colombia and Guyana.21“ELN in Venezuela,” InSight Crime, January 28, 2020, https://www.insightcrime.org/venezuela-organized-crime-news/eln-in-venezuela/; Venezuela Investigative Unit, “Colombia and Venezuela: Criminal Siamese Twins,” InSight Crime, May 21, 2018, https://www.insightcrime.org/investigations/colombia-venezuela-criminal-siamese-twins/. The armed groups and the regime have a complex scheme in which the former operate the mines and the latter sells the minerals through stateowned companies. The ELN also plays a political and military role, with presence in at least thirteen of twenty-four Venezuelan states. As political tensions have increased, this group has pledged to defend the Maduro regime from foreign intervention.22“The ELN is now Latin America’s biggest guerrilla army and has vowed to defend Maduro’s government in the event of a foreign intervention.” Bram Ebus, “Venezuela’s Mining Arc: a Legal Veneer for Armed Groups to Plunder,” Guardian, June 8, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/08/venezuela-gold-mines-rival-armed-groups-gangs.

The human and environmental impact in and around these mines—which produce not only gold, but also coltan, bauxite, and thorium—must be a matter of international attention. As reported in the most recent report by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), illicit mining is commonly tied to other criminal activities, such as murders, human trafficking, child labor, sexual exploitation, and massive ecological destruction.23“Venezuela: UN report highlights criminal control of mining area, and wider justice concerns’” UN News, July 15, 2020, https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/07/1068391; “The Nexus of Illegal Gold Mining and Human Trafficking in Global Supply Chains: Lessons from Latin America,” Verité, July 2016, https://www.verite.org/the-nexus-of-illegal-gold-mining-and-human-trafficking-report/. In 2018, the municipalities of El Callao and Guasipati—two key mining areas—witnessed rates of 620 and 458 homicides per one hundred thousand inhabitants, respectively.24“Informe Anual de Violencia 2018,” Observatorio de Violencia, 2018, https://observatoriodeviolencia.org.ve/news/ovv-lacso-informe-anual-de-violencia-2018/. In the Orinoco Mining Arc region, in mines run by FARC and ELN—and aided by Maduro-directed colectivos, criminal bands, and members of the armed forces—workers are subject to torture, forced prostitution, and even massacres, according to anecdotes from Venezuelans who escaped to Colombia.25Algimiro Montiel and Jorge Benezra, “Crimen Organizado Controla la Explotación de Oro en Venezuela,” Venezuela, El Paraíso de los Contrabandistas, https://smugglersparadise.infoamazonia.org/story. The ecological impact is also alarming. While the precise scale of the environmental damage is unknown, the illicit mining partnership between Maduro and criminal groups operates unchecked in the Orinoco Mining Arc, home to Venezuela’s largest national parks, natural reserves, and indigenous ancestral lands. The use of mercury—which is taking a biological toll on miners and surrounding villagers—is contaminating waterways around the mines to such an extent that it will require decades to reverse.26Luis Alvarenga, “Alejandro Álvarez: La Mayor Tragedia En El Arco Minero Del Orinoco Es La Contaminación Por Mercurio” Amnistía Internacional, September 4, 2019, https://www.amnistia.org/en/blog/2019/09/11553/la-mayor-tragedia-en-el-arco-minero-es-la-contaminacion-por-mercurio.

The Maduro regime is not only involved in the illegal extraction of gold and other minerals, but also participates in their sale to international markets via malign global actors and regional allies. In a desperate move to mitigate the gasoline shortage causing massive unrest across Venezuela, the Maduro regime paid Iran $500 million in gold bars for 1.5 million barrels of fuel delivered from April to June 2020.27Patricia Laya and Ben Bartenstein, “Iran Is Hauling Gold Bars Out of Venezuela´s Almost-Empty Vaults” Bloomberg, April 30, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-30/iran-is-hauling-gold-bars-out-of-venezuela-s-almost-empty-vaults. Tehran-based carrier Mahan Air, sanctioned by the US Treasury Department for direct support of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force, flew at least sixteen times between Tehran and Caracas as part of this agreement to bring technical teams to help repair PDVSA facilities and fly the gold to Iran.28“Treasury Designates IRG-QF Weapons Smuggling Network and Mahan Air General Sales Agents,” US Department of Treasury, press release, December 11, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm853. Given tightening international sanctions, Iran has now become Maduro’s partner of choice in the sale of illicit gold.29Scott Smith and Joshua Goodman, “Venezuela Turns to Iran for a Hand Restarting its Gas Pumps,” Associated Press, April 23, 2020, https://apnews.com/41a1b06ec3a64dd292d06ffd2a542e23.

In addition to Iran’s increasing role in the Maduro regime’s illicit activities, the Maduro regime sold 73.2 tons of Venezuelan gold to companies in the United Arab Emirates and Turkey in 2018. One of those companies—a Belgian-owned gold consortium with presence in Dubai and refineries in Uganda—bought 30 percent of the total gold sold by the Venezuelan Central Bank (BCV).30Lorena Meléndez and Lisseth Boon, “How Venezuela’s Stolen Gold Ended Up in Turkey, Uganda and Beyond” InSight Crime, March 21, 2019, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/venezuelas-stolen-gold-ended-turkey-uganda-beyond/. But, despite the regime’s sales in 2018, gold reserves in the BCV grew by eleven tons. Given the regime’s known criminal partnership with the ELN and FARC, the gold is likely to have been mined illegally, sold to the regime at a significant discount, moved to Guyana, Suriname, or Nicaragua, and exported as originating in those countries rather than Venezuela in order to avoid detection.31For further understanding of the connections between ELN and Maduro’s regime, see Ebus, “Venezuela’s Mining Arc: a Legal Veneer for Armed Groups to Plunder.”

The Caribbean is also a transport hub for illegally mined Venezuelan gold. To avoid scrutiny, private operators declare the gold destined to the United States, Europe, and the United Arab Emirates as “goods in transit,” according to a recent investigation conducted by Dutch authorities in Aruba.32A recent investigation conducted by Dutch authorities in Aruba and Curaçao revealed a scheme for gold trade that commercialized Venezuelan gold in markets around the globe, in places such as Dubai. For further detail, see “Pista 1: Los 50 Kilos de Oro” Runrun.es. https://www.connectas.org/especiales/fuga-del-oro-venezolano/pista-de-aterrizaje-1.html. Another key player in the illicit gold trade is the small country of Suriname, which has become a hub for exporting illicitly mined gold through an elaborate scheme that directly implicated former senior government officials.33Douglas Farah and Kathryn Babineau, “Suriname: The New Paradigm of a Criminalized State,” Center for a Secure Free Society, March 2017, https://www.securefreesociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Global-Dispatch-Issue-3-FINAL.pdf.

Europe as an Often-Forgotten Node: Money Laundering and Corruption

In addition to regional allies and sympathetic extra-regional malign actors, the Maduro regime has also made extensive use of European banking structures to move and hide billions of dollars in assets. Europe has been slower than the United States to make serious efforts to track and seize the billions of dollars in regime-connected proceeds that have been stashed in its financial systems, or to close the loopholes that allow the money to flow through European banks. US officials have repeatedly asked the European Union—particularly Spain, a favorite destination for Maduro regime insiders (see below)—to enforce its own rules banning Maduro officials’ visits, and to designate regime officials as criminal actors.34Author interviews with senior officials at the US State Department, Treasury Department and Department of Justice, March-April 2020.

Whether a result of lack of political will or overdue legal and financial reforms (or both) in EU member states and other non-EU countries in Western Europe to disrupt this flow of illicit funding, Europe can do more to step up its role in dismantling a key node for the Maduro regime’s international web of criminal activities. This is why Interim President Juan Guaidó formally asked the European Union in January 2020 to have a more robust and more agile response to the Maduro regime’s illicit activities, specifically in preventing the Venezuelan “blood gold” trade.35Brian Ellsworth and Vivian Sequera, “Update 2-Venezuela´s Guaido seeks EU ‘Blood Gold’ Designation for Informal Mining,” Reuters, January 9, 2020, “https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-politics/venezuelas-guaido-seeks-eu-blood-gold-designation-for-informal-mining-idUSKBN1Z82HP.”

“The illicit activities linking actors in Switzerland, Andorra, and Spain to the Maduro regime are not the same as the criminal partnerships with malign states such as Russia and Iran. But, they are a telling sign of how the regime’s illicit tentacles can reach actors in Western Europe’s democratic system.”

The Maduro regime’s use of Europe to move its fortunes is a seldom-analyzed aspect of its criminal toolkit. Companies and banks across Europe, particularly in Switzerland and Andorra, and European subsidiaries of Russian banks, have been identified in criminal cases and investigative reports as moving regime-linked funds. In Switzerland, for instance, Geneva-based Compagnie Bancaire Helvetique SA (CBH) is alleged to be the bank of choice for many high-level Venezuelan officials.36Charlie Devereux and Michael Smith, “A Swiss Bank Keeps Cropping Up in Venezuelan Corruption Cases,” Bloomberg, October 15, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-10-15/swiss-bank-cbh-keeps-cropping-up-in-venezuelan-corruption-cases. An ongoing criminal case in Florida implicates several Venezuelan elites in a multi-billion-dollar money-laundering case involving CBH and several of its past and current officers. In March 2020, a Swiss court required the bank to release documents and accounts related to the case.37Jay Weaver and Antonio Maria Delgado, “Huge U.S. Money-Laundering Probe Targets Widening Circle of Venezuelan Elites,” Miami Herald, February 26, 2020, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/article240482546.html. Based on the released evidence, US federal prosecutors are conducting an investigation into Luis and Ignacio Oberto, two Venezuelan bankers who allegedly developed a sham loans scheme through shell companies, in which PDVSA borrowed money and sent inflated payments to the Swiss accounts of the two bankers. The alleged money-laundering case would account for more than $4.5 billion, one of the largest of three cases involving Venezuelans in South Florida.38For a full discussion of the Alejandro Andrade case, see Jay Weaver, “Venezuela’s Ex-Treasurer Sentenced to 10 Years for South Florida Money-Laundering Scheme,” Miami Herald, November 27, 2018, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/article222226225.html. For further details, see Jay Weaver and Antonio Maria Delgado, “Venezuela’s Business Elite Face Scrutiny in $1.2 Billion Money Laundering Case,” Miami Herald, November 3, 2019, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/article236793383.html.

In another case, the now-defunct bank Banca Privada d’Andorra in the principality of Andorra served as a money-laundering hub for Venezuelan nationals tied to the Chávez regime. In 2018, two former Venezuelan officials, including a relative of the former head of PDVSA, Rafael Ramírez, were charged with corruption, along with twenty-six other individuals, after $2.3 billion in PDVSA bribery money was found to have moved through the bank and its subsidiaries in Panama and Uruguay.39“Venezuelan Ex-Officials Charged in Andorra over $2.3bn Graft Scheme,” BBC World News, September 14, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45507588.

More recently, Spain has been in the spotlight after a Spanish judge summoned Raul Gorrín, the sanctioned Venezuelan businessman and head of television outlet Globovisión, in an ongoing probe of alleged corruption and money laundering.40The Spanish judiciary is conducting an investigation of alleged corruption involving former officials of the Venezuelan government, some of them linked to other cases heard by federal courts in the United States. For more details see: “Imputan a Raúl Gorrín en España por el saqueo de PDVSA,” Runrun.es, February 20, 2020, https://runrun.es/noticias/398962/imputan-a-raul-gorrin-en-espana-por-el-saqueo-de-pdvsa/. He is accused of developing a scheme that allowed him and his collaborators to illegally take money from PDVSA to Spain. The US Treasury Department sanctioned Gorrín in 2019 for leading a currency-exchange network that produced billions of dollars for Maduro and his cronies.

There are also signs of political tolerance of the Maduro regime in Spain. In January 2020, Spanish Transportation Minister José Luis Ábolos met Maduro’s vice president, Delcy Rodríguez, in her aircraft on the tarmac at the Madrid airport for several hours, despite the EU prohibition on such meetings and such flight landings.41Sam Jones, “Airport Meeting Lands Spanish Minister in Venezuela Controversy,” Guardian, January 24, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/24/airport-meeting-lands-spanish-minister-venezuela-controversy-jose-luis-abalos#maincontent The next month, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez referred to Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s opposition leader, rather than the interim president, although the European Union officially recognizes the Guaidó administration.42“Sánchez llama a Guaidó “líder de la oposición” y cierra filas con Ábalos,” EFE, February 12, 2020, https://www.efe.com/efe/espana/politica/sanchez-llama-a-guaido-lider-de-la-oposicion-y-cierra-filas-con-abalos/10002-4171726 And, there has been a significant rise in Venezuelans purchasing Spanish real estate, often in cash, in cities across Spain, from Madrid to Salamanca.43Raphael Minder, “On Spain’s Smartest Streets, a Property Boom Made in Venezuela,” New York Times, July 29, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/29/world/europe/spain-property-boom-venezuela.html. For example, Hugo “El Pollo” Carvajal, the longtime head of Venezuela’s military intelligence under Chávez and Maduro, fled to Spain to live in his luxury estates when he feared his life was in danger.44“Hugo Carvajal: la Fuga en España del Exjefe de Inteligenica Venezolana que EEUU. Considera ‘Vergonzosa,’” BBC News, November 14, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-50417317. With the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, more opportunities could arise for regime-connected individuals to engage in money-laundering operations in Europe and beyond where there are near-insolvent companies in need of capital.

The illicit activities linking actors in Switzerland, Andorra, and Spain to the Maduro regime are not the same as the criminal partnerships with malign states such as Russia and Iran. But, they are a telling sign of how the regime’s illicit tentacles can reach actors in Western Europe’s democratic system. Given that enforcement of EU rules is largely in the hands of member states’ governments and their agencies, these countries—as well as non-EU countries that participate in the single market system—must all play a more assertive role in dismantling the illicit activities supporting the Maduro regime.

Policy Recommendations

To the extent that the Maduro regime continues to profit from illicit activities in collaboration with regional and international partners, democratic forces inside and outside Venezuela will continue facing a well-entrenched foe with strong incentives to maintain its grip on power. Its drug and gold partnerships with Colombian terrorist groups, and its money laundering and corruption schemes across the Atlantic, are only a few of the nodes in a much broader global criminal network. The regime’s strong political, economic, and military relations with geopolitical players such as Iran, Russia, and China are key sources of support for Maduro and his cronies.

The Maduro regime, with its extensive international array of state and non-state allies, has proven to be resilient and adaptable in the face of strong US and international sanctions, managing to find the seams in the global financial system, shift operations to new geographical locations, or bring new partners to its fold. The interim government and its allies in the international community are essentially facing an opponent engaging in asymmetrical tactics. How, then, can they tap new policy toolkits at their disposal? What specific actions can international allies coordinate for a more comprehensive and assertive approach to tackling the regime’s illicit activities?

The key to combatting this criminal network is integrating the authorities and capabilities across the US government, in collaboration with trusted regional partners (and, importantly, Europe) to tackle the Maduro regime’s regional and global reach. Underpinning this approach is the objective of helping to recover democratic institutions in Venezuela. This approach includes the following actions.

- Creating a cross-agency task force in the US government that strategically incorporates specific resources and expertise of the intelligence community and relevant US agencies—including the Department of Treasury, Department of State, Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Defense—to tackle the diverse fronts of the Maduro-led criminal enterprise with a coherent, multifaceted strategy of asset forfeiture, financial-account seizures, front-company closures, indictments and prosecutions, visa revocations, information sharing with allies, and other actions. Each department has unique authorities that, when utilized in concert, can have tremendous impact that shorten the time the criminals have to adapt. This has worked best in the past when coordinated through the National Security Council (NSC), with the power to convene principals and deputies, when necessary, to elevate the issue for sustained policy focus. This must include looking at all facets and actors of the BJCE, rather than just Venezuela, to find ways to reduce the resiliency and adaptability of the structures that allow for the flow of multiple illicit products.

- Engaging in more continuous and robust diplomacy on the criminalized nature of the Maduro regime, the strategic, economic, and social consequences to the regime, and persistent, coordinated responses. This needs to go hand in hand with improving financial information-sharing and coordinating sanctions with trusted partners such in the European Union and Latin America, including the Caribbean. This would significantly reduce the spaces in the financial sectors in which the regime could operate. The Lima Group has agreed—at least on paper—to implement asset-tracing tactics and forfeiture measures, although no actions have yet been taken. This should be addressed so implementation begins in the shortest time possible. The Organization of American States (OAS) and its Department Against Transnational Organized Crime could be useful avenues for pursuing sanctions on illicit gold and other extractive industries.

- Working closely with Brazil, Colombia, Guyana, and Ecuador to increase border control—with the help of technologies such as monitoring drones, as well as increased personnel—with the goal of disrupting illicit supply chains usually focused in border regions. This would include cutting off resupply lines to FARC dissidents and ELN groups inside Venezuela, as well as trafficking networks moving products out of the region.

- Creating a multinational working group with policymakers and experts from the interim government of Venezuela, the United States, European Union and key member states, Lima Group, and CARICOM that focuses on devising policy strategies to confront the threat of irregular armed groups and transnational crime in order to provide the pathway for the restoration of democratic institutions.

Conclusion

The confluence of nefarious state and nonstate actors, and an interconnected global network of criminal activities, provides the Maduro regime with the financial, diplomatic, and military resources it needs to survive. This support is critical for further anchoring the regime’s position at a time when Venezuelans grapple with a pandemic that is deepening one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. Failing to combat the criminal nature of the regime and isolate it from its malign allies will only prolong the suffering of the Venezuelan people, and will increase the threats to security and stability in the hemisphere.

The next brief in this series will take a deep dive into how the Iran-backed Hezbollah terrorist group, with its network of operators and sympathizers, provides the Maduro regime with little-known, but significant, support, and how that support is a threat to democracy in Venezuela and security in the region.

Subscribe to the #AlertaVenezuela newsletter

To receive future editions of the #AlertaVenezuela newsletter each week, sign up below!

Image: Cover image credit: REUTERS/Carlos Garcia Rawlins