Seven years from the Syrian revolution, the conflict in Syria has altered the course of history for the generation coming of age in the region. It has killed, wounded, or displaced millions of Syrians, worsened regional sectarianism, raised the risk of war between Israel and Iran, generated the worst refugee crisis since World War II, and created a new and more pernicious wave of violent radicals. Its effects extend beyond the region, shaping the outcome of politics around the world.

US Policy in Syria: A Seven-Year Reckoning, by Atlantic Council Senior Fellow Faysal Itani and New America International Security fellow Nate Rosenblatt, is a retrospective analysis of key US policy decisions in Syria and how they shaped the Syrian revolution’s outcome. It also draws broader lessons about US policy in the region based on the United States’ actions in the twenty-first century’s most acute and profound geopolitical crisis, and outlines the key policy challenges ahead in Syria.

Executive summary

Analytical findings

- By calculating that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad would fall quickly in the face of protests, the United States lost valuable time to shape the outcome of the Syrian uprising. Nor did it plan adequately for alternative scenarios, which would have allowed it to better identify and organize mainstream revolutionary forces before better-organized extremists undermined them.

- The United States wrongly calculated that the crisis could be contained to Syria itself. Instead, it quickly spread and enabled international terrorism, displaced millions to foreign countries, and bound itself to global geopolitics, all of which harmed US interests.

- The US decision not to strike the regime for using sarin gas against civilians in August 2013 was critical and costly. The regime’s subsequent agreement to surrender its chemical and biological weapons was a failure for three reasons:

- It did not do so. The Syrian government has used chemical weapons, including sarin gas, against civilians at least thirty times since August 2013.

- It undermined international norms against these weapons’ use more generally, likely encouraging other regimes to employ them against their populations.

- It weakened US credibility in Syria and undermined actual partners among Syrian rebel groups while signaling to others that the United States was unreliable.

- The campaign against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) was artificially compartmentalized from the broader war, highlighting the lack of US interest in the latter’s core drivers. This helped the conflict to progress in a manner that has harmed US interests.

- The United States missed a potential opportunity to apply pressure on Russia and Iran over the civil war, despite years of de-conflicting while fighting ISIS—an effort that helped Iran and Russia.

- Without enforcement mechanisms, cease-fires will last only as long as the Syrian regime, and, to a lesser extent the armed opposition, want them to last. They ought not be a pillar of policy except in areas that are not highly contested (e.g., Kurdish areas, Syria’s south).

- This conflict is mainly about Assad’s future. He will not negotiate away a political monopoly that he has killed tens of thousands to preserve. Iran and Russia cannot force him to do so unless they can credibly threaten to abandon him, which they will not do as it would carry unacceptable risks and uncertainty over any successor’s foreign policies and viability.

- There cannot be a meaningful political transition—and therefore an enduring peace—without Assad’s departure, which is a stated US policy goal. Yet he will not compromise, unless perhaps in response to a credible US-backed threat or use of military force. On the current course, Assad will defeat the insurgency and be reelected president in 2021.

Introduction

This paper is a retrospective analysis of key US policy decisions in Syria and how they shaped the Syrian revolution’s outcome. It also attempts to draw broader lessons about US policy in the region based on the United States’ actions in the twenty-first century’s most acute and profound geopolitical crisis. Finally, it outlines the key policy challenges ahead in Syria.

The United States had abandoned its policy of aggressive democracy promotion by the time Syrian protests erupted in 2011. Syrians were slow to understand this, which contributed to some of the mistakes they made. Yet while Syrians have much to account for in their revolution’s failure, the United States was the international actor with the greatest capacity to alter events in Syria, deliberately or not, and its actions deserve special scrutiny.

The Syrian revolution has altered the course of history for the generation coming of age in the region.

The Syrian revolution has altered the course of history for the generation coming of age in the region. It has killed, wounded, or displaced millions of Syrians, worsened regional sectarianism, raised the risk of war between Israel and Iran, generated the worst refugee crisis since World War II, and created a new and more pernicious wave of violent radicals. Its effects extend beyond the region, shaping the outcome of politics around the world.

Some argue the Pax Americana is over, certainly in the Middle East.1Hal Brands, “The ‘American Century’ Is Over, and It Died in Syria,” Bloomberg, last updated March 8, 2018, http://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-03-08/the-american-century-is-over-putin-and-assad-killed-it. It is more accurate to say the Middle East has changed, but not in ways that make the useful projection of US power impossible. Syria’s failed revolution could encourage introspection and a revitalization of the US role in the Middle East in pursuit of US values and interests. Alternatively, Syria could be a precursor to recurrent future conflicts in a post-Pax Americana Middle East, not necessarily in the US or regional interest.

These authors recognize the fiendishly difficult policy problem that Syria has presented. But we continue to believe the US role in the region is vital for US interests and, properly deployed, a potential force for progress in the region itself.

A new beginning

In June 2009, six months after his inauguration, President Barack Obama visited Cairo University to announce a reset of US relations with the Muslim world. His speech, “A New Beginning,” was intended to repair the relationship between the United States and Muslim world after the George Bush administration’s belligerent policies in the Middle East. The speech made the requisite mention of individual freedoms and political liberty, but also the “controversy about the promotion of democracy in recent years.” President Obama stated the United States would remain committed to “governments that reflect the will of the people,” but crucially emphasized that “no system of government can or should be imposed upon one nation by any other.”2Jeff Zeleny and Alan Cowell, “Addressing Muslims, Obama Pushes Mideast Peace,” New York Times, last updated June 4, 2009, www.nytimes.com/2009/06/05/world/middleeast/05prexy.html?action=click&contentCollection=Politics&module=RelatedCoverage®ion=EndOfArticle&pgtype=article&mtrref=www.nytimes.com&gwh=E7EF499D8A957C7BCC1CA142FC25592F&gwt=pay.

These caveats are important because they made clear that the administration would avoid complex entanglements in the Middle East in pursuit of democratization. The Iraq War had given rise to an anti-war sentiment that helped put Barack Obama in the White House. Those views, the president shared, inspired a policy mantra in his administration: “don’t do stupid shit.”3Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine,” Atlantic, last updated April 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/. While admittedly glib, the motto revealed deep skepticism about the projection of US power toward ambitious ends, especially in the Middle East.

It was the Arabs’ bad luck, then, that they launched their “Arab Spring” uprisings just as the United States was drifting away from the core US foreign policy tenet of activist liberal internationalism, and the US role as enforcer of that order. While US power has not always served democracy abroad (and has often done the opposite) it has also been the most common tool for pressuring foreign governments, mobilizing opposition, deterring aggression by adversaries, and, where interests and principles overlap, enforcing international humanitarian norms. President Obama sought a “new beginning,” but not for the region. Despite his rhetorical appeals to shared values, this new beginning marked a less involved US role in the region and a deep reluctance to intervene or pressure regional governments in pursuit of those values.

… Misplaced faith in the inevitability of justice in a moral universe contributed to the first of several unfortunate policy misjudgments over Syria: the expectation Bashar al-Assad would go quickly, and that the central US contribution should be calling and preparing for his departure.

In the abstract, the Obama administration would have liked to see liberal democracies emerge in the Arab world, including in Syria. But it would not do any heavy lifting to bring them about.4The NATO intervention in Libya might be seen as an exception to this point, but it was largely pursued by Europe and was, by Barack Obama’s admission, his presidency’s “worst mistake”—see “Barack Obama Says Libya Was ‘Worst Mistake’ of His Presidency,” Guardian, last updated April 11, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/apr/12/barack-obama-says-libya-was-worst-mistake-of-his-presidency. Instead, the United States either expected or hoped that things would fall into place accordingly, and that its chief duty was to be “on the right side of history”—which presumably favored liberalism and democracy. This historical optimism—a sharp contrast with the president’s own skepticism about US power—is reflected in a line attributed to Martin Luther King Jr.: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” The president was so fond of this quote that he had it woven into a rug in the Oval Office.5Matt Lewis, “Obama Loves Martin Luther King’s Great Quote—But He Uses It Incorrectly,” Daily Beast, last updated January 16, 2017, https://www.thedailybeast.com/obama-loves-martin-luther-kings-great-quotebut-he-uses-it-incorrectly.

But this belief in a moral universe, where justice would inevitably prevail against evil, was more a declaration of faith than a statement of values the United States would advance abroad. This misplaced faith in the inevitability of justice in a moral universe contributed to the first of several unfortunate policy misjudgments over Syria: the expectation Bashar al-Assad would go quickly, and that the central US contribution should be calling and preparing for his departure.6Helene Cooper, “Washington Begins to Plan for Collapse of Syrian Government,” New York Times, last updated July 18, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/19/world/middleeast/washington-begins-to-plan-for-collapse-of-syrian-government.html.

When it became clear Assad would not step down, the United States did not commit to shaping the Syrian revolution’s outcome. By 2013, Syria’s atavisms and competing regional forces overwhelmed the initially peaceful protest movement. The revolution was fully militarized.

The so-called Free Syrian Army, or FSA, was the military incarnation of the Syrian protest movement, originally conceived to protect demonstrators. It was less a coherent ideological movement and more a network of rebel franchises, but it was not hostile to the United States as it fought Iran and Hezbollah. The FSA fought not only Assad, his backers in Iran and Russia, and various Shia militias, but also extremist Sunni Islamist militants flush with foreign money from sympathetic individuals and governments.

In the crucial months in which the FSA’s fate was being decided, the president revealed not only his strong bias against military intervention or serious proxy backing for the rebels, but deep skepticism about the Syrian opposition itself. In his 2013 interview with Jeffrey Goldberg for the Atlantic, President Obama described one side of the Syrian conflict as Assad’s “professional army,” fighting for “huge stakes” and supported by “large states”—Russia and Iran. Arrayed against this army, on the other side, was “a farmer, a carpenter, an engineer who started out as protestors and suddenly now see themselves amid a civil conflict.”7Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine.” Although this could be seen as contempt toward the rebels, it is perhaps better understood as indicating a deep malaise toward the Middle East, and an almost nonexistent belief in the US ability to shape events positively there, especially through military action. Whatever its origins, the administration’s insistence that the revolutionaries were amateurs despite their good intentions implicitly justified noninterventionism.

Opponents of intervention also repeatedly insisted that “we don’t know who the rebels are.”8See, for example, Zack Beauchamp, “The War in Syria, Explained,” Vox, last updated April 13, 2018, https://www.vox.com/2017/4/8/15218782/syria-trump-bomb-assad-explainer. This confusion was particularly acute in 2011-12, when the United States had the greatest leverage over the revolution’s outcome. For example, Buck McKeon, the former Republican chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, said: “my understanding is we don’t know who the good guys and bad guys are.” See John T. Bennett, “Is Syria Becoming a Proxy War between U.S. and Russia?” U.S. News & World Report, June 21, 2012, https://www.usnews.com/news/blogs/dotmil/2012/06/21/is-syria-becoming-a-proxy-war-between-us-and-russia. Despite these statements, enterprising analysts used open source media and personal contacts to map out opposition groups and their capabilities in painstaking detail throughout the conflict. Moreover, the US intelligence services that maintained close contact with FSA units as part of a covert train and equip program did not lack for information either.

The move to reject decisive military intervention against the regime, whether to overthrow it or force it to compromise, raised the question of what exactly the United States should do instead. The United States settled on a policy of containment—not of the regime or its backers, but of the war itself. This was the United States’ second misjudgment: the premise that the war would burn itself out and perhaps fragment Syria, but that regional allies could be protected from its spillover. This was not realistic. The rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and its eventual expansion in Iraq and Syria is one example that shows that containment was a failed policy. The displacement of millions of refugees to neighboring countries and Europe, where their presence polarized local politics, is another.

The third fateful US decision was the unwillingness to attack the regime after it killed hundreds of civilians using sarin gas in the Damascus suburbs in August 2013. This violation of President Obama’s “red line” on chemical weapons use in Syria, an offhand remark made at a time the administration did not take seriously that Assad would use any means to remain in power, went unpunished.9James Ball, “Obama Issues Syria a ‘Red Line’ Warning on Chemical Weapons,” Washington Post, last updated August 20, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/obama-issues-syria-red-line-warning-on-chemical-weapons/2012/08/20/ba5d26ec-eaf7-11e1-b811-09036bcb182b_story.html?utm_term=.c7897eaa9016. At first a US attack seemed likely, but the president clearly felt trapped and chose to seek congressional approval. This stalling created a space for Russia to offer a deal to dismantle Syria’s chemical weapons program, which the United States accepted.10Mark Landler and Jonathan Weisman, “Obama Delays Syria Strike to Focus on a Russian Plan,” New York Times, last updated September 10, 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/09/11/world/middleeast/syrian-chemical-arsenal.html?pagewanted=all.

The chemical deal was problematic in three ways. First, the regime did not stop using chemical weapons.11Michael Grunwald, “Ben Rhodes and the Tough Sell of Obama’s Foreign Policy,” Politico, last updated May 11, 2016, https://www.politico.eu/article/ben-rhodes-barack-obama-foreign-policy-tough-sell-war-middle-east-afghanistan-libya-syria; Scott Shane, “Weren’t Syria’s Chemical Weapons Destroyed? It’s Complicated,” New York Times, last updated April 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/07/world/middleeast/werent-syrias-chemical-weapons-destroyed-its-complicated.html. The Syrian government has launched at least thirty chemical attacks since August 2013.12Sara Kayyali, “Chemical Weapons Resurface in Syria,” Human Rights Watch, last updated February 3, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/03/chemical-weapons-resurface-syria.

This means that the Obama administration bargained for a temporary reduction in Syria’s chemical weapons at the price of possibly signaling to Assad that he was safe from any US action. The second failure of the deal was that it eroded international norms against using chemical weapons, setting precedent for future dictators to use them when under duress. Third and finally, it signaled the end of any serious prospect of victory for the mainstream, nonextremist opposition in Syria. It undermined US credibility as being serious about getting involved in Syria and highlighted to both fighters and the local population that they were essentially on their own and at the mercy of the regime and extremists. Many would choose the latter.

It is impossible to debate hypothetical alternatives and construct scenarios for Syria with any degree of confidence because the possible outcomes are nearly infinite. There is no certain way to know how events in Syria would have unfolded had the administration made different decisions during this stage of the conflict. But that uncertainty ought to have informed administration thinking as well, which began with principles adopted after the Iraq War, making the intervention appear as nothing but an Iraq redux—a “slippery slope.”

The anti-ISIS campaign

The rise of ISIS sealed the Syrian revolution’s fate. The emergence of ISIS and al-Qaeda-linked groups removed any flexibility that remained in US Syria policy. The administration decided that ISIS had to be defeated as quickly as possible and with minimum risk to US personnel. Any anti-Assad efforts would only distract from and complicate the anti-ISIS fight. Rebels who refused to drop the fight against Assad to fight ISIS exclusively would find themselves misaligned with US priorities and deprived of support.13Rebecca Collard, “The U.S. Challenge of Turning Syria’s Ragtag Rebels into a Fighting Force,” Time, last updated September 30, 2014,

http://time.com/3446604/free-syria-army-hazem-assad/. Since Assad had no intention of pausing his war effort, this meant the rebels were besieged by regime forces and ISIS even as US attention shifted away from them.

In a last-ditch effort to save its revolution—although it did not know it at the time—the Syrian opposition argued at the United Nations that confronting Sunni radicalism in Syria without supporting efforts to overthrow Assad would address the proximate cause of a more profound disease.14National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, “Remarks of SOC President Hadi al Bahra to the UN Press Corps at the 69th UN General Assembly,” last updated September 22, 2014, https://www.etilaf.us/preshadi_unstatement. Sunni radicals would continue to flock to Syria to fight Assad, just as, by this time, Shia militants were being recruited from Afghanistan and Iraq and flown into the Syrian theater by Iran. It is true that opposition supporters have sometimes lazily argued that Assad is the “root cause” of all evil in Syria and should be removed from power. Noninterventionists would reject this root cause argument, noting it cannot be addressed at an acceptable cost. However, completely decoupling US counterterrorism strategy from Syria’s broader war was ultimately harmful.15Hannah Allam, “It’s Official: U.S. Will Build New Syrian Rebel Force to Battle Islamic State,” Olympian, last updated October 16, 2014, http://www.theolympian.com/news/nation-world/national/article26084077.html.

Launched in 2014, the anti-ISIS campaign overlapped with another key development in US foreign policy that influenced US thinking on Syria. The secret back-channel meetings between the United States and Iran, which began in July 2012 and continued in earnest in 2013, had made enough progress by the time the counter-ISIS coalition was announced that the Obama administration did not want to jeopardize a potential nuclear deal.16Indira A.R. Lakshmanan, “‘If You Can’t Do This Deal … Go Back to Tehran,’” Politico, last updated September 26, 2015,

https://www.politico.eu/article/if-you-cant-do-this-deal-go-back-to-tehran-iran-us-nuclear-deal/. “The sale of Syria to Iran was baked into the Iran deal” according to a long-term Syria observer with close ties to the current and previous administrations. On the other hand, at least some administration officials, publicly and privately, deny any such linkage. The fair conclusion is that outsiders cannot be absolutely sure of just how much this consideration shaped Syria policy. Indeed it may have played an exclusively subconscious role in administration thinking, and it was one of many strong drivers of nonintervention.

Whatever the exact reason, the United States was eager to wage the anti-ISIS war in a compartment—ignoring the link between the sectarian civil war’s radicalizing effect and the rise of Sunni extremists. Such acknowledgement would have pressured the administration to end the war, and certainly to remove Assad from power. Instead, the United States focused on the problem to which it had a ready and comfortable solution: air strikes and proxy warfare. That meant putting the “boots on the ground” that were previously taboo.17Robin Wright, “Trump to Let Assad Stay until 2021, as Putin Declares Victory in Syria,” New Yorker, last updated December 11, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/sections/news/trump-to-let-assad-stay-until-2021-as-putin-declares-victory-in-syria; Since the 2014 anti-ISIS coalition announcement, the United States has deployed two thousand troops and spent roughly $13 million a day on its campaign. Yet since the September 11 attacks, the US public has largely supported military campaigns against Sunni extremists. This kept the administration in a political comfort zone as well.

This deliberate splitting of the anti-ISIS effort from Syria’s broader war sometimes led to bizarre policy outcomes, such as in the so-called train and equip program of Syrian rebels. The program was a debacle in which the US Department of Defense committed to training several thousand Syrian fighters against ISIS. Only a few dozen volunteers passed the vetting process, and the United States failed to commit to defending them should they come under regime attack.18Paul Mcleary, “Carter: ‘Awfully Small Number’ of Syrian Rebels Being Trained by U.S.,” Foreign Policy, last updated July 7, 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/07/07/carter-awfully-small-number-of-syrian-rebels-being-trained-by-u-s/; “My understanding of that question is that we don’t foresee that happening anytime soon,” Carter said. “But a legal determination, I’m told by the lawyers, has not been made.” See David Welna, “Syrian Rebels Will Face ISIS, but the U.S. May Not Have Their Backs,” NPR, March 14, 2015, https://www.npr.org/2015/03/14/392945308/syrian-rebels-will-face-isis-but-the-u-s-may-not-have-their-backs. The insistence that US-aligned fighters ignore the regime was one reason the train and equip program fizzled—the other being the relative strength of extremist groups by the time the handful of program graduates reentered the battlefield.

This deliberate splitting of the anti-ISIS effort from Syria’s broader war sometimes led to bizarre policy outcomes.

The Russian intervention in September 2015 irreversibly cemented the boundaries delinking the ISIS war from the Syrian civil war. The introduction of Russian forces and anti-aircraft systems into the Syrian theater was a strong deterrent against serious US involvement outside the anti-ISIS fight.19Jonathan Marcus, “Russia S-400 Syria Missile Deployment Sends Robust Signal,” BBC, last updated December 1, 2015, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-34976537. This strengthened the noninterventionists’ argument, as they could cite the risk of a catastrophic military confrontation with Russia. Avoiding antagonizing Syrian forces—and Russian forces by extension—became not just a policy choice but a military necessity. By fall 2015, the United States could not fly through Syrian airspace without Russia’s approval. Paradoxically, even as the administration sought to avoid such a collision, the president himself dismissed claims of Russian strength or the idea that its deployment in Syria posed a threat, insisting it was entering a “quagmire” and that its actions demonstrated weakness rather than strength.20James S. Robbins, “A Strategic Muddle in Syria,” U.S. News & World Report, last updated October 12, 2016, https://www.usnews.com/opinion/articles/2016-10-12/obama-wont-admit-were-fighting-a-proxy-war-with-russia-in-syria.

Despite the American defeat of ISIS, the Syrian conflict will continue to drive radicalization in the Middle East. The regime’s survival in western Syria will not address its dysfunctional political economy, sectarian character, or severe repression of much of the Syrian population.

Coordinating US and Russian forces in Syria evolved into the “de-confliction” program, which resulted in several years of carefully coordinated air strikes—sometimes through as many as twenty phone calls a day.21Guy Taylor, “U.S. Military Uses Russian ‘Deconfliction’ Line 20 Times a Day to Separate Jets over Syria,” Washington Times, last updated October 5, 2017, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/oct/5/us-russia-use-military-deconfliction-phone-20-time/. But since it further isolated its anti-ISIS fight from the wider Syrian conflict, the United States lost all meaningful leverage. As a result, years of high-level military communications with Russia, and by extension Iran and Syria, brought no military or political progress on Syria’s broader conflict, which depended on adversaries’ willingness to make at least some concessions. In the absence of coordination between these powers, other diplomatic efforts went nowhere.

Despite the American defeat of ISIS, the Syrian conflict will continue to drive radicalization in the Middle East. The regime’s survival in western Syria will not address its dysfunctional political economy, sectarian character, or severe repression of much of the Syrian population. ISIS, al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, and their successor organizations will recruit victims from Syria’s war, not least the large and disenfranchised population of several million Syrian refugees and internally displaced persons. Additionally, the consuming US focus on the ISIS fight and its artificial separation from the broader Syrian conflict left the latter to take its own unimpeded course. The implications of the rise of Iranian-backed Shia militias will become known only after this phase of the Syrian war resolves.

Post-ISIS Syria

The anti-ISIS campaign did not address any of the core struggles of the Syrian war. In the wake of ISIS’s defeat, four fronts have reemerged alongside one crucial new one.

The US-Kurdish alliance and its fallout

The United States’ closest ally in Syria is a Kurdish separatist group whose political aims not only undermine US policy for a united Syria but also threaten to unravel US-Turkish relations. This ally is the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), derived from and influenced by the Turkish Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). For the first year of the counter-ISIS coalition, from 2014 to 2015, Syrian YPG and Iraqi Kurds were on the front lines resisting ISIS’s territorial expansion.22Dexter Filkins, “The Fight of Their Lives,” New Yorker, last updated September 29, 2014, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/09/29/fight-lives. By late 2015, the counter-ISIS coalition had formed the Syrian Democratic Forces as a local partner to continue fighting ISIS—an umbrella organization to include an Arab component, but nonetheless dominated by the Kurdish YPG militia.23“Global Powers Seek to Revive Diplomatic Process,” Economist, last updated February 12, 2016, http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=1363937520&Country=Syria&topic=Politics. These Arabs are mainly from former ISIS territory and are interested in garnering US support for recapturing their hometowns from ISIS.24Kheder Khaddour, “A Shattered Relationship,” Carnegie Middle East Center, last updated September 27, 2017, http://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/73212.

In addition to being a US-designated terrorist group, the PKK is a historic enemy of Turkey, which itself is a NATO ally of the United States. This is an inherently unstable situation that neither Turkey nor the United States has found a way around. To further complicate matters, the United States wants to keep Syria territorially unified, as explained in January 2018 by then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Meanwhile, the YPG, and its political arm the Democratic Union Party (PYD), claim an anarcho-syndicalist ideology calling for extreme decentralization, which is hybridized with a Kurdish ethno-nationalism. The United States seeks to stabilize Kurdish-held Arab areas captured from ISIS, but it is wading into latent conflict: Arab-Kurdish suspicion runs high and there is a history of ethnic conflict.25“Mistrust Mars Deal between Syrian Arab Rebels, Kurds,” EKurd Daily, last updated April 8, 2013, http://ekurd.net/mismas/articles/misc2013/4/syriakurd772.htm; Aris Roussinos, “After Raqqa: The Challenges Posed by Syria’s Tribal Networks,” The Jamestown Foundation, last updated June 16, 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/raqqa-challenges-posed-syrias-tribal-networks/.

To make matters worse, there is a high probability that the regime and Turkey will seek to sabotage US stabilization efforts in Kurdish-held areas taken from ISIS, despite (or because of) the presence of hundreds of US soldiers there. One direct result of Turkish anxiety over the emerging PYD state is its campaign against Kurds in Afrin.Aaron Stein, “What Turkey’s 26Afrin Operation Says about Options for the United States,” Atlantic Council, February 14, 2018, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/what-turkey-s-afrin-operation-says-about-options-for-the-united-states-2.

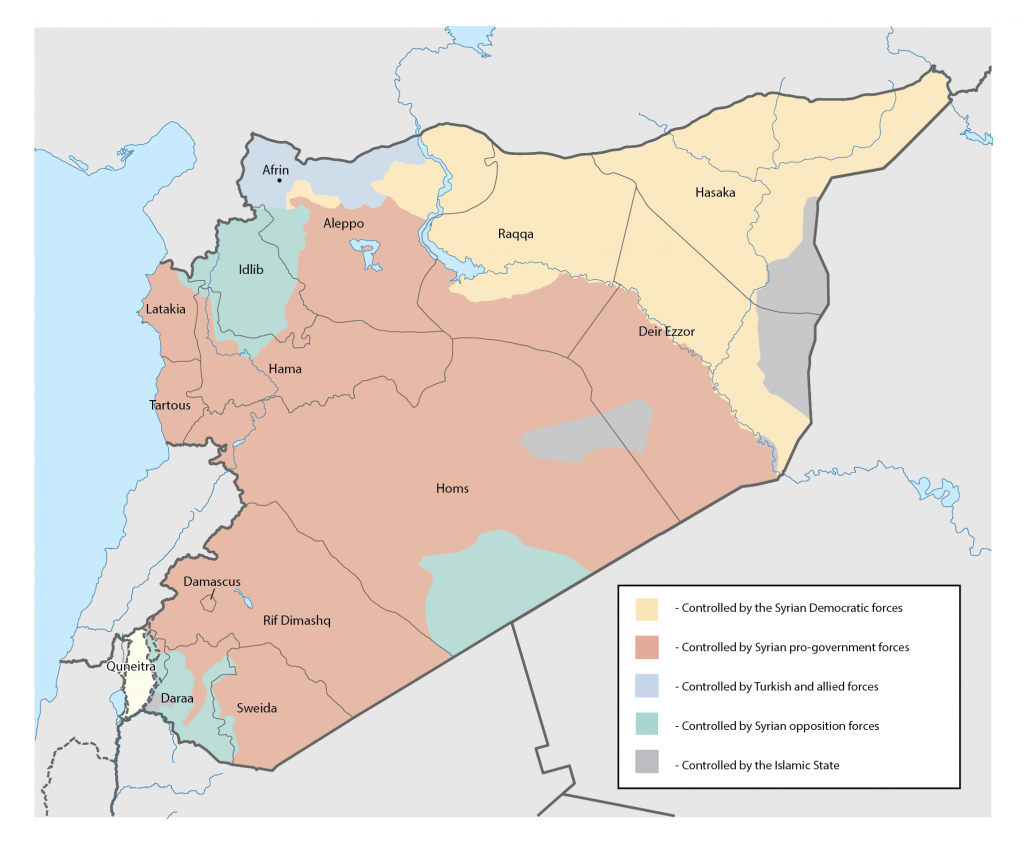

In January 2018, the Turkish military launched an operation into this largely Kurdish region of northern Syria. The basic goal of this operation is to defang Kurdish militants in the area and continue ongoing efforts to prevent them from connecting territory under their control with a much larger Kurdish territory to the east (see map above).27Aaron Stein and Michael Stephens, “The PYD’s Dream of Unifying the Cantons Comes to an End,” Atlantic Council, August 25, 2016, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/the-pyd-s-dream-of-unifying-the-cantons-comes-to-an-end.

It is also, to an extent, an expression of Turkish frustration at being unable to pursue the more ambitious goal of going after the YPG in the US-controlled northeast. In this case, it is likely to achieve its military goals.

The Syrian regime’s consolidation process is unlikely to prioritize resettling the estimated eleven million Syrians displaced by fighting … Their return would likely place an unbearable burden on state capacity and finances.

A ‘healthier’ Syria: regime consolidation

Since it turned the tides of the war in its favor in 2015, the Syrian government has planned to consolidate its gains with an eye to preventing any future opposition through punitive military action and forced displacement. Using a “starve or surrender” campaign, it recaptured opposition holdouts in densely populated urban areas.28Nour Alakraa, “Syria’s Cycle: Siege, Starve, Surrender, Repeat,” Wall Street Journal, last updated March 23, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/syrias-cycle-siege-starve-surrender-repeat-1521817360.

Roughly half a million Syrians—nearly 2.5 percent of the country’s pre-war population—have been subjected to this tactic in neighborhoods like Zabadani and Darayya (Damascus), al-Waer (Homs), and Eastern Aleppo (Aleppo). After surrendering, these areas are largely depopulated of usually aggrieved Sunnis. The regime then uses reconstruction plans and funds to reassert control over strategically important areas. There is a blueprint in the regime’s reconstruction plans to push out mainly Sunni lower-class communities—the parts of Syria’s cities most likely to participate in the revolution. The blueprint was passed in 2012: Decree 66/2012 provided the legal authorization for city planners to rezone “unauthorized or illegal housing areas” in Damascus. This blueprint was approved by the Syrian parliament in January 2018 to be applied throughout the provinces of the country and will likely be part of future efforts to entice foreign investors and change the character of once-hostile areas.29Joseph Daher, “Decree 66 and the Impact of Its National Expansion,” Atlantic Council, last updated March 7, 2018, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/decree-66-and-the-impact-of-its-national-expansion.

The Syrian regime’s consolidation process is unlikely to prioritize resettling the estimated eleven million Syrians displaced by fighting, both internally and as refugees. Their return would likely place an unbearable burden on state capacity and finances. Additionally, because they are largely Sunni from areas hostile to Assad, their permanent displacement represents a net gain for the regime. The war’s destruction and disruption have therefore had paradoxical effects on the Syrian government’s fortunes: they have undoubtedly shrunk the regime’s geographic reach and weakened its capabilities. However, they have also spared it the financial, political, and security strain of controlling millions of dependent and resentful Syrians. As Assad himself has put it: “We lost many of our youth and infrastructure [in the war] but we gained a healthier and more homogenous society.”30Mariam Elba, “Why White Nationalists Love Bashar Al-Assad,” The Intercept, last updated September 8, 2017, https://theintercept.com/2017/09/08/syria-why-white-nationalists-love-bashar-al-assad-charlottesville/.

The fight for Idlib

Anti-Assad rebel forces in Idlib benefit from the northwestern province’s rugged terrain and largely Sunni, anti-regime demography. As a result, rebels there will not be easily defeated. But they are not unified. Infighting mainly involves al-Qaeda-affiliated Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) on the one side (formerly Jabhat al-Nusra), and Nourredine al-Zinki and Ahrar al-Sham on the other. Neither the extremists of HTS and Ahrar al-Sham nor the guns for hire in Nourredine al-Zinki are worth international support despite some coming under Turkish domination. Many are merely an indication of the extent to which non-ISIS anti-Assad forces have become radicalized over the course of the conflict. Communities in Idlib clearly chafe under the rule of these radicals, but while the United States fought its battles against ISIS, these are the only ones left with guns in the remaining areas of “opposition-held Syria.”31Haid Haid, “The Regime Push against HTS in Idlib Could Backfire,” Chatham House, January 2018, https://syria.chathamhouse.org/research/the-regime-push-against-hts-in-idlib-could-backfire.

‘De-escalation’ in the south?

While some would argue that Syria’s south is an example of the success of the cease-fire agreement brokered by the United States and Russia in 2017, it is more accurate to say that the south is different from the rest of Syria. The cease-fire and “de-escalation effort” brokered in southern Syria was the first meaningful diplomatic foray of the Donald Trump administration into the Syrian conflict. Then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson trumpeted it as “our first indication of the United States and Russia being able to work together in Syria.”32Jeff Mason and Denis Dyomkin, “Partial Ceasefire Deal Reached in Syria, in Trump’s First Peace Effort,” Reuters, last updated July 7, 2017, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-mideast-crisis-syria-ceasefire/partial-ceasefire-deal-reached-in-syria-in-trumps-first-peace-effort-idUKKBN19S2DA. And the southern front has largely been quiet, with the important exception of a simmering Israeli-Iranian confrontation (more below).

But the cease-fire holds not because the United States cooperated with Russia, but because the Syrian government has not broken it yet. No matter who brokers cease-fires, it is Assad who decides whether they hold. The Syrian government sees the south as nonessential (for now) given the regime’s already-strained resources. This is mainly because the so-called Southern Front, a unified band of anti-Assad rebels, has never advanced beyond southern Syria and because neighboring Jordan has essentially shut down its operations, seeking a rapprochement with the regime.33Mohamed Al-Daameh, “Jordan Denies Syrian Rebels Trained for Damascus Attack on Its Territory,” Asharq al-Awsat, February 2014, https://eng-archive.aawsat.com/mohamed-al-daameh/news-middle-east/jordan-denies-syrian-rebels-trained-for-damascus-attack-on-its-territory. This situation has no parallel elsewhere in Syria.

A new front line and potential war

The issues above were apparent before the anti-ISIS campaign, but a new volatile fault line emerged along the Israeli-Syrian border while US attention was elsewhere. The tit-for-tat exchange between an Iranian drone, Israeli jets, and Syrian anti-aircraft weapons in February 2018 is precisely the kind of seemingly minor, confusing incident that can spark a wider war between Israel and Iran and its proxies.34Anshel Pfeffer, “Two Days on, Israel Still Puzzled Why Iran Sent Drone into Its Airspace,” Haaretz, February 12, 2018, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israel-still-puzzled-why-iran-sent-drone-into-israeli-airspace-1.5809571.

As the Syrian conflict winds down, a powerful and fully mobilized Hezbollah poses enough of a threat to Israel. But it is being furnished with new Iranian weapons that can easily reach Tel Aviv. On the one hand, Iran’s weapons transfer to Hezbollah is inevitable as long as a pro-Iranian regime controls the Syrian-Lebanese border: Iran can and will arm Hezbollah with weapons that allow it to secure its gains in Lebanon and Syria.35Sam Dagher, “What Iran Is Really Up to in Syria,” Atlantic, last updated February 14, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/02/iran-hezbollah-united-front-syria/553274/. On the other hand, for Israel, the transfer of new weapons capabilities and newfound Iranian strategic depth in Syria are likely unacceptable.36“Israeli Minister: ‘We Will Prevent Iranian Activity in Lebanon as We Did in Syria,’” Middle East Monitor, last updated January 31, 2018, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180131-israeli-minister-we-will-prevent-iranian-activity-in-lebanon-as-we-did-in-syria/. By securing the Syrian regime at little direct cost, Iran is arguably the biggest winner in the Syrian war. This new balance of power in the region has made war with Israel more likely.

Reflections

It is easy to criticize US diplomats and decision makers for their mistakes on Syria in hindsight. But the problem with their choices on Syria is that they were predicated on the assumption that the United States could not and should not shape conflicts abroad in any ambitious way, especially in the Middle East. This was a departure from the self-evident benefit of projecting power to protect local populations from government predations and to reduce the gains of historic rivals such as Iran and Russia.

Through this noninterventionist lens, the United States misread key aspects of Syria’s conflict. In the first two years of Syria’s revolution, the instinct to avoid regional entanglements led to, or encouraged, faulty assumptions about the capabilities and intent of the Syrian regime. Those assumptions led to an underestimation about the extent to which the war in Syria would affect the region and the world. These two early assumptions undermined a chance to support the Syrian revolution in a way that might have constructively shaped its outcome.

There are no certain answers, but if the United States is to draw lessons from the Syrian revolution, it cannot be content with saying there were no better options than the very few it exercised.

To a very large extent, this attitude emerged from a combination of faith in a rules-based international order and an aversion to military intervention. But the rules-based international order offered no answer to the regional and international obscenities of the Syrian war, and single-minded noninterventionism ruled out a US shift to the language of power and coercion that could remove or constrain Assad.

In Perception and Misperception in International Politics, Robert Jervis describes how “a dramatic and important experience often hinders later decision-making by providing an analogy that will be applied too quickly, easily, and widely.”37Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 220. It was the administration’s processing of the Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya wars that arguably decided US policy before the insurgency’s radicalization, the emergence of ISIS, the Russian intervention, and other complications. President Obama could not imagine an intervention in Syria being anything other than a slippery slope to a large-scale, open-ended, quixotic US military deployment. This was the burden the Iraq War imposed on US decision-making over Syria. As a consequence, the Syrians should perhaps be considered the biggest casualties of the Iraq War after the Iraqis.

There will always be unanswered and unanswerable hypothetical questions about Syria: Should the United States have armed the rebels in 2012? Should the United States have bombed Syrian government military targets after they used sarin gas in August 2013? What would have happened had the United States intervened on purely normative or humanitarian grounds through no-fly zones or airdrops, after it became clear that entire towns were being leveled and starved into surrender? There are no certain answers, but if the United States is to draw lessons from the Syrian revolution, it cannot be content with saying there were no better options than the very few it exercised.

Complex conflicts like Syria’s have multiple possible trajectories. Options emerge if there is a strong, lasting commitment to develop them. For example, if the United States had been interested in supporting the Syrian revolution early on, it might have found the opposition willing to cohere around a limited set of ideas and goals. The United States also did not need to stage a ground invasion and occupation of Syria to turn the tide of the war, as President Obama has implied, especially before Iran and Russia committed their own forces at a large scale. The mere threat of US air strikes in Syria in August 2013 sent Assad loyalists fleeing to Beirut. By taking one or two concrete steps to support imperfect Syrian revolutionary forces, the United States may have created more options than it at first thought.

The United States

The most important debate about the US role in Syria has little to do with the conflict and everything to do with the role the United States envisions for itself in the region. Despite their different sentiments towards Iran, the Obama and Trump administrations share a deep and abiding skepticism about the United States’ ability to shape the Middle East. They agree that American power is of limited use there beyond protecting narrow, core US strategic interests: counterterrorism; ensuring the flow of hydrocarbons; and guaranteeing the security of Israel.

Both presidents regularly refer to the lessons from what they see as the ill-fated wars in Iraq and Libya. Yet it remains the case that there is nowhere else in the world with as deep and widespread a deficit in political legitimacy as the Middle East. In an interdependent world where conflicts metastasize and spread, the incompetent despots of the region are not guarantors of stability, but powder kegs. Governments built upon fear, coercion, and brutality end as violently as they often start. When opportunities to change them arise with strong local support, is it truly in US national interest to ignore them?

The lesson from the Iraq War is not that the United States cannot and should not play a substantive role in shaping the region, including in situations like Syria’s. Instead, the lesson is that it must remain active and engaged in learning about these societies, holding governments accountable when they abuse their power, and reflecting the link between political legitimacy and US security in policy. In that sense, Syria was, and continues to be, a lost opportunity.

The competition with Iran and Russia in particular revealed that the United States is suffering from a deeper malaise as a superpower. It is not quite clear what the United States stands for in the Middle East. Iran has allies that it seeks to protect at all costs. Russia insists it supports states as complete sovereigns over their domains, regardless of the path the rulers of those states take to acquire and keep power. Meanwhile, the United States calls for Assad to step down while doing little to ensure this outcome, even as its small-scale support for certain insurgent groups helps keep the war going. Of course, Russia and Iran are neither consistent nor noble in pursuing their ideals, but they do appear to know what they want without making apologies for it. What kind of power does the United States want to be? What compelling story can it tell to counter Iran’s and Russia’s?

That one cannot spread democracy by force in the Middle East is an obviously true but glib response to all intervention arguments. The United States’ most reliable and established ideological compass is the belief that political stability and prosperity emerge from the consent of the governed—that is, when people’s rights are protected and human security is assured—whereas illegitimate government leads to eventual collapse. Sovereignty is earned, not a given. Of course, a superpower will always have broad interests that conflict and often trump its ideals, but without faith in the latter there is little direction or efficacy in policy, and ground is ceded to other parties who possess it.

Lessons for US policy

- Guard against policy prejudices. All administrations and leaders bring their own baggage and filters through which they assess policy options. The Obama administration was staffed by intelligent people who valued evidence-based analysis, but leadership often clung tenaciously to prior beliefs about US policy in the Middle East, which compromised decision-making about Syria.

- Adapt. The administrations that struggle most in the Middle East are those that cling dogmatically to positions regardless of conditions. George W. Bush believed the United States should overthrow dictators and install democracies, even as it became clear it could not. The Obama administration believed the United States should avoid complex involvement in the Middle East, even as the cost of nonintervention in Syria became increasingly clear. Rather, it is preferable to have a set of principles about the region and identify opportunities to advance them when those opportunities arise.

- Manage expectations. The Obama administration continued to claim it was committed to the ouster of Bashar al-Assad as part of a political transition in Syria. Yet it was clear that, after the rise of ISIS and the compartmentalization of the fight against Sunni jihadists in Syria, the United States was not interested in supporting efforts to bring about meaningful political change. This gap between actions and aspirations confused or alienated Syrians and discredited the United States among allies and adversaries.

- Expand the breadth of data collection and analy-sis. The Syrian conflict made clear that there are vast deficiencies in the way the US government collects and analyzes data in the Middle East. There are myriad new tools to analyze complex conflicts. Small research teams have demonstrated an ability to identify Syrian opposition groups and track their activities in high detail and at low cost. Such tools should be considered as part of a broader investment in learning about the region across the US government.

- Pick a side and back it. The United States held out for a political transition in Syria, but rather than give the opposition the means to force one, it exerted most of its energy on keeping the diplomatic process alive. This compromised the United States’ position in negotiations by signaling to rivals that in the absence of a hopeful outcome, it would settle for process. It also over-complicated the US relationship with the opposition, which never trusted the United States to go beyond limited support and rhetoric. The United States must either support a side or prioritize reaching a deal. By trying to do both, it failed at each. Iran and Russia faced no such problem.

Image: U.S. President Barack Obama speaks about the vote on Capitol Hill on his request to arm and train Syrian rebels in the fight against the Islamic State while in the State Dining Room at the White House in Washington, September 18, 2014. The U.S. Senate approved Obama's plan for training and arming moderate Syrian rebels to battle Islamic State militants on Thursday, a major part of his military campaign to "degrade and destroy" the radical group. REUTERS/Larry Downing