A Tunisia-based company operated a sophisticated digital campaign involving multiple social media platforms and websites in an attempt to influence the country’s 2019 presidential election, as well as other recent elections in Africa. In an exclusive investigation that began in September 2019, the DFRLab uncovered dozens of online assets with connections to Tunisian digital communications firm UReputation. On June 5, 2020, after conducting its own investigation, Facebook announced it had taken down more than 900 assets affiliated with the UReputation operation, including 182 user accounts, 446 pages, and 96 groups, as well as 209 Instagram accounts. The operation also involved the publication of multiple Francophone websites, some going back more than five years.

In a statement, a Facebook spokesperson said that these assets were removed for violating the company’s policy against foreign interference, which is coordinated inauthentic behavior on behalf of a foreign entity. “The individuals behind this activity used fake accounts to masquerade as locals in countries they targeted, post and like their own content, drive people to off-platform sites, and manage groups and pages posing as independent news entities,” the spokesperson said. “Some of these pages engaged in abusive audience building tactics changing their focus from non-political to political themes, including substantial name and admin changes over time.”

“Although the people behind this activity attempted to conceal their identities and coordination,” Facebook added, “our investigation found links to a Tunisia-based PR firm, UReputation.”

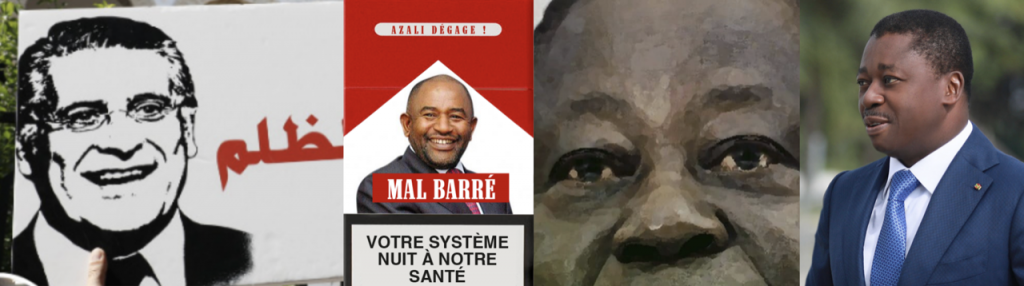

The influence operation, which for research purposes the DFRLab has given the designation Operation Carthage in reference to the ancient empire located in what is now modern-day Tunisia, was based around a collection of inauthentic Facebook pages targeting people in 10 African countries. According to open source evidence and a review of assets subsequently provided by Facebook, the operation exerted its influence in multiple African presidential campaigns, including supporting Togolese President Faure Gnassingbé’s February 2020 reelection campaign, as well as former Ivorian President Henri Konan Bédié’s campaign for the upcoming October 2020 election in Côte d’Ivoire. Approximately 3.8 million Facebook accounts followed one or more of these pages, with nearly 132,000 joining operation-administrated groups and over 171,000 following its Instagram accounts.

The DFRLab has previously reported on instances in which digital communications companies profit by engaging in coordinated inauthentic behavior on Facebook and other platforms. In May 2019, Facebook removed more than 250 assets created by Archimedes Group, an Israeli-based digital influence company that had established inauthentic pages in at least 13 countries, including Tunisia. A similar takedown took place in August 2019, when it removed online assets connected to public relations companies in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

These examples, as well as others ranging from Russia to the Philippines, demonstrate how otherwise legitimate digital communications companies and PR firms have taken up disinformation campaigns and online influence operations involving coordinated inauthentic behavior as part of their suite of services. While it remains unknown how many digital communications firms now engage in disinformation for profit — what has been referred to as “disinformation as a service” — investigations such as this one are discovering their involvement in influence operations with increasing frequency.

While companies engaging in disinformation for profit potentially expose themselves to enormous reputational risk, the potential revenues that can be made through running covert campaigns and influence operations are apparently enough to sway at least some digital communications companies toward the practice. Additionally, the ease at which a company can establish new brand identities through the incorporation of shell companies lessens these risks; if a company is caught and banned by a social media platform, there is nothing to stop it from setting up shop under a new name and in a new country to continue their business.

In this particular instance, the influence network cut across a large swath of countries and topics, notably elections. It appears to have been financially motivated, as there was no ideological consistency across the content. Much of the material was not outright false, but the pattern of behavior and the myriad connections across the network show a widespread intent to mislead — most specifically about the motives and connections of the network itself. According to Facebook, the operation invested the equivalent of around $331,000 in the form of Facebook ads, primarily paid in euros and U.S. dollars.

While much of the network engaged on political topics, candidates, and elections, this case is primarily about inauthentic influence operations for profit, and the temptations faced by otherwise legitimate communications firms to engage in it. The actors operating this particular network did not draw a distinction between a strategic communications firm, whose interests lie in serving the needs of a client, and journalism, where transparency, accountability, and facts are paramount. By not drawing that distinction, innumerate voters across multiple countries in Africa might have made their electoral decisions based in part on misleading information from inauthentic sources, potentially influencing the course of elections.

Image: Presidential candidates that were promoted or targeted in the influence operation, left to right: Nabil Karoui of Tunisia, Azali Assoumani of Comoros, Henri Konan Bédié of Côte d’Ivoire, and Faure Gnassingbé of Togo. (Sources: Facebook/hkb2020.com/tousfaure.com)