Building a navy fighting machine

Table of contents

- Key terminology

- The navy’s approach to strategy development and force planning

- The sources of the problem

- Problem definition

- Key issues shaping problem solution

- Recommendations

- First recommendation: Establish a new assistant secretary of the navy

- Second recommendation: stand-up the navy strategy cell

- Third recommendation: Stand-up the force planning directorate

- Resourcing the recommendations

- Conclusion

- About the author

Key terminology

This paper uses five key terms. The first two, force design and force development, are precise US Navy terms that are not interchangeable.

Force design is the innovation and the determination of future Navy ships, aircraft, and weapon systems, along with a warfighting concept for a twenty-year and beyond timeframe. Force development is the adaptation and modernization of Navy in-service ships, aircraft, and weapon systems, along with a warfighting concept within a two-to-seven-year timeframe. The difference between these two official Navy terms may seem arcane: force design is all about the future force, and force development is all about the current force. However, both address Navy requirements based on an appraisal of US security needs, and then choose naval capabilities (along with a warfighting concept) to meet those requirements within fiscal limitations.

The following terms are also important for the reader’s comprehension.

- Force planning is the more commonly understood term—used in place of force design and force development—and is used across Congress, defense media, academia, and industry. While force planning is not an official Navy term, the term is used in this paper to encompass both force development and force design.

- Force structure is used by the Congress to mean the number and types of combat units the Navy can generate and sustain, as well as to represent the Navy’s combat capability.

- Budget is an informal and shortened expression to encapsulate all Navy activities in the Defense Department’s Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) system, especially the programming activity.

The navy’s approach to strategy development and force planning

The US Navy’s approach to strategy development and force planning in 2023 is not working. Strategy development is on life support and force planning uses an incremental approach of buying marginally better and more expensive versions of the same platforms the Navy has relied upon for decades. In effect, it is producing the Navy’s force structure one ship class at a time, without reference to an overall Navy strategy and force plan to field an integrated, aligned, and synchronized “Navy fighting machine.”1Borrowed from, Bradley A. Fiske, The Navy as a Fighting Machine (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1916). He wrote the Navy, “must first determine the units of the force and their relation to each other: it must, in other words, design the machine.” Its use herein represents the ultimate objective of Navy force planning, i.e., an integrated combination of air, surface, sub-surface, and cyberspace lethality for the Navy to fight as a unified whole. Moreover, this approach is delivering an unaffordable fleet over too long a procurement time. Proposals for developing new capabilities are viewed as threats to in-service platforms and programs, thereby blocking innovation.

Navy F/A-18E Super Hornets prepare to launch from the USS Harry S. Truman in support of Exercise Trident Juncture 18. Credit: US Navy, Navy Petty Officer 3rd Class Adelola Tinubu.

Congress, defense media, defense analysts, the Defense Department, and independent US government agencies have all found fault with the US Navy’s strategy development and force planning. Most notably, Congress has expressed its dissatisfaction.

In December 2017, Congress mandated a Navy with 355 crewed ships, a goal based on the Navy’s 2016 Force Structure Assessment (FSA) and, in February 2020, Representative Joe Courtney (D-CT) complained to then Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper about, “the lack of a shipbuilding plan and the [Donald] Trump administration not delivering a strategy to build a 355-ship Navy.”2Mac [R-TX-13] Rep. Thornberry, “H.R.2810 – National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018,” Pub. L. No. 115–91 (2017), http://www.congress.gov/; Mark T. Esper, “Chapter 7: The Politics of Building a Better Navy,” in A Sacred Oath: Memoirs of a Secretary of Defense During Extraordinary Times, First edition. (New York, NY: William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2022), p.196. In December 2021, Congress mandated the Navy to submit the Battle Force Ship Assessment and Requirement Report on its force structure plans for the near, middle, and far terms to meet the combatant commanders’ requirements using Defense Department-approved scenarios.3Please see section 1017 of, Rick [R-FL] Sen. Scott, “S.1605 – National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022,” Pub. L. No. 117–81 (2021), http://www.congress.gov/. However, Congress reacted with little enthusiasm for the Navy’s thirty-year shipbuilding plan for fiscal year 2023 (FY2023), despite its being the first such report from the Navy to Congress in more than three years, and was similarly unimpressed by the following year’s iteration. This has led Congress to mandate the establishment of an independent National Commission on the Future of the Navy in December 2022 to determine the size and force mix of the fleet by mid-2025.4Section 1092 of, Peter A. [D-OR-4] Rep. DeFazio, “H.R.7776 – James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023,” Pub. L. No. 117–263 (2022), http://www.congress.gov/.

This litany of events—particularly the unprecedented direction for the Navy to submit the Battle Force Ship Assessment and Requirement Report, the establishment of an independent National Commission on the Future of the Navy, and the assignment to the commandant of the Marine Corps of sole responsibility to develop amphibious warfare ships requirements—indicates Congress’ displeasure with Navy force planning. Moreover, the inability of the Department of Defense (DoD) and Navy leaders to consistently state how many ships the Navy needs to meet its requirements may be a driving factor in Congress’ decision to legislate these unprecedented mandates. During the first seven months of 2022, DoD leaders suggested five different targets for the objective size of the Navy—316, 327, 367, 373, and five hundred.5Lara Seligman, Lee Hudson, and Paul McLeary, “Inside the Pentagon Slugfest over the Future of the Fleet,” POLITICO, July 24, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/07/24/pentagon-slugfest-navy-fleet-00047551.For further background see, Sam LaGrone, “Lack of Future Fleet Plans, Public Strategy Hurting Navy’s Bottom Line in Upcoming Defense Bills,” USNI News, June 18, 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/06/18/lack-of-future-fleet-plans-public-strategy-hurting-navys-bottom-line-in-upcoming-defense-bills; Sam LaGrone, “Navy Lacks ‘Clear Theory of Victory’ Needed to Build New Fleet, Experts Tell House Panel,” USNI News, June 4, 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/06/04/navy-lacks-clear-theory-of-victory-needed-to-build-new-fleet-experts-tell-house-panel; Mark Cancian Saxton Adam and Mark Cancian, “The Spectacular & Public Collapse of Navy Force Planning,” Breaking Defense, January 28, 2020, https://breakingdefense.sites.breakingmedia.com/2020/01/the-spectacular-public-collapse-of-navy-force-planning/. In addition, the use of three options in both the FY2023 and FY2024 thirty-year shipbuilding plan—rather than a single projection—handicaps congressional understanding of the Joe Biden administration’s goals concerning the future size and composition of the Navy, and assessing the Navy’s proposed FY2024 shipbuilding budget, five-year shipbuilding plan, and thirty-year shipbuilding plan. Moreover, to follow its mantra of providing best military advice to civilian leadership, the Navy must have a preferred option for what it needs to get the job done, and, most importantly, must assess the risk to the United States if it does not get the resources it needs (see Table 2).

As Dr. Scott Mobley pointed out in his November 2022 Proceedings essay, the Navy largely focuses on programming and budget to develop the means for strategy while “devaluing the strategic underpinnings for rationalizing and justifying those means.”6Captain Scott Mobley, US Navy, Retired, “How to Rebalance the Navy’s Strategic Culture | Proceedings – November 2022 Vol. 148/11/1,437,” U.S. Naval Institute, November 2022, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/november/how-rebalance-navys-strategic-culture.

Navy force planning uses a piecemeal approach—“buying at the margin [fewer, but] better [and more expensive] versions of the same [type] of platforms [the Navy] has relied upon for decades”—that is delivering an unaffordable fleet over too long a procurement time.7Christian Brose, The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare, First edition. (New York, NY: Hachette Books, Hachette Book Group, 2020). Navy force planning almost always occurs in a resource-constrained environment imposing a zero-sum approach, in which proposals for new capabilities are frequently viewed as threats to in-service platforms, thereby blocking innovation. At the end of the day, the Navy’s new platforms, weapons, and systems are quite similar to what is already in the fleet.

The preponderance of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) platform and capability staffs each focus on a single platform or capability. No one looks at all the platforms and capabilities as an integrated, collective whole. No single staff entity ensures all these individual platform and capability staffs are integrated by a well-articulated, comprehensive strategy and warfighting concept to achieve the required strategy-force match.

The Navy cannot create a lasting OPNAV organizational structure to ensure its strategy drives its force planning and its budget in that order. OPNAV cannot conduct its business “with strategic intent” at all times in its key processes. Because it operates within the Defense Department’s mandated five-year Future Years Defense Program and is focused on the budget, OPNAV tends to concentrate on numerous process-centric products, which, coupled with cascading short-term urgent projects, frequently sees its strategic guidance displaced, or even lost, in the sausage making.

The continuing need to reconcile the interface between the Navy’s strategy with its mid-range to long-range forecasts, and between the Navy’s budget and its short-term timelines and all-consuming fiscal pressures, has eluded OPNAV. Numerous OPNAV reorganizations since the early 1980s underscore this observation. As a 2010 Center for Naval Analyses study highlighted: “successive CNOs have sought to make [OPNAV] responsive to their needs—chief among which is usually construction of a balanced and integrated program and budget.”8Peter M. Swartz and Michael C. Markowitz, “Organizing OPNAV (1970 – 2009),” January 1, 2010, https://www.cna.org/reports/2010/organizing-opnav-1970-to-2009. They failed and, as a result, the Navy continues to address its force requirements incrementally, which frustrates innovation, alarms Congress, and delivers fewer, more expensive, and almost always bigger platforms. The various uncrewed surface vessels and aircraft may break the bigger-is-better paradigm, yet they are arriving too slowly.

The sources of the problem

The causes of the Navy’s problem with its approach to strategy development and force planning are numerous and diverse.

Divergent CNO proclivities prevent strategic consistency

Effective force planning suffers from insufficient strategic consistency between chiefs of naval operations (CNOs). The historical record suggests these service chiefs seem to believe they must differentiate themselves from their predecessors, with their own distinct, separate strategy—or what is typically a strategic, aspirational plan rather than a strategy with ends, ways, and means. As Dr. Peter Haynes explained in his book, Toward a New Maritime Strategy:

In the political climate of Washington, a place that demands constant change and where only new ideas can be ensured a hearing, strategic statements have a shelf life. Navy leaders have to replace or update their ideas or risk being seen as too slow in responding to changes in the domestic political or international security environments.9Peter D. Haynes, Toward a New Maritime Strategy: American Naval Thinking in the Post-Cold War Era (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2015), p. 246.

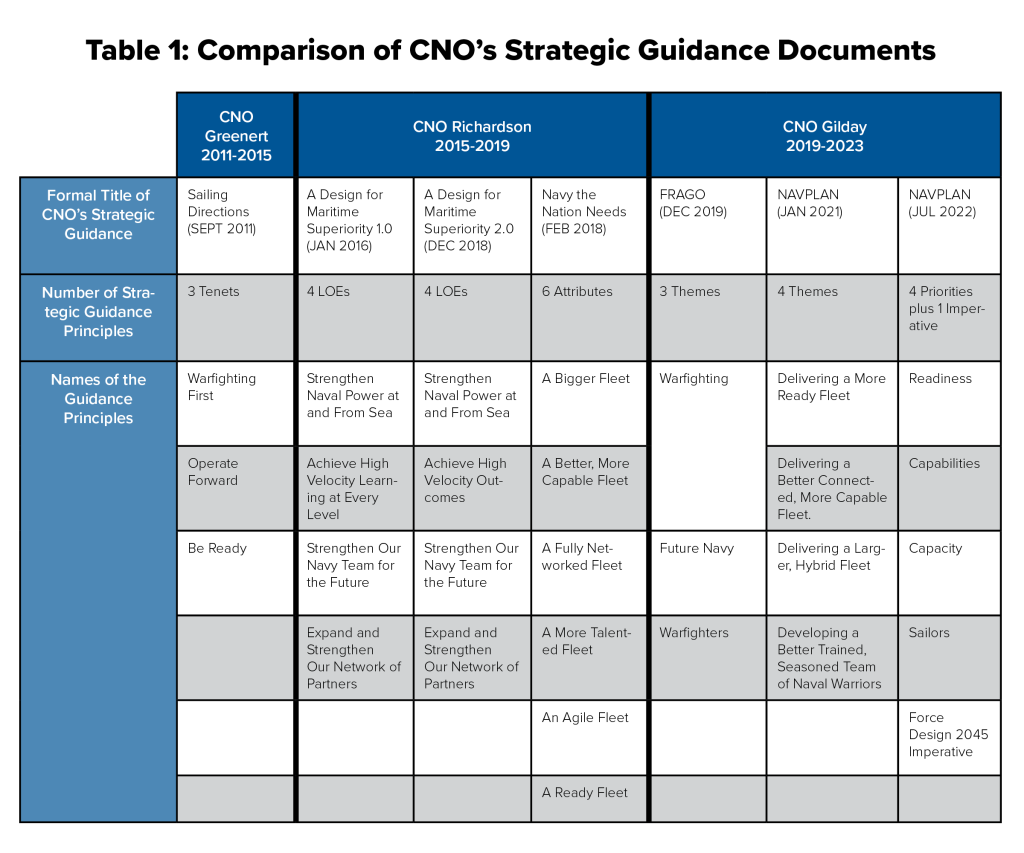

Assuredly, senior Navy leaders would agree that, regardless of who is the CNO, the Navy has enduring institutional objectives and the benefits of consistency would be enormous for strategy development and force planning. There would be: assured continuity of strategic direction over the fielding of major platforms and weapons systems; no requirement for an incoming CNO to craft a “new” Navy strategic direction from whole cloth; unity of effort on the Navy’s way ahead based on organizational agreement hammered out at four-star updates; a consistent Navy message for strategic communications; and reduction in false starts and nonproductive efforts (see Table 1).

The service needs each CNO to build upon what has gone on before so that the Navy can benefit from continuous unity of effort over time. The service also needs a consistent planning process, and not a completely new version to accompany the incoming CNO’s new strategy. The challenge is to sustain consensus in a planning and acquisition process that runs a decade or more, and is instigated by a CNO who typically serves a four-year tenure.

OPNAV’s budget process dominates strategy and force planning

OPNAV remains focused on the budget as its overarching and defining process, believing strategy can be generated during the budget process. This narrow focus constrains the development of long-range strategies and plans to address transcendent challenges and opportunities. There is an irreconcilable difference between the needs of the budget process and the strategy-development process.

In a 2021 interview, a former deputy director of the Integration of Capabilities and Resources Directorate (OPNAV N8), Irv Blickstein, provided an explanation of why the budget process dominates. First, it is impossible to follow literally the linear prescript of strategy, requirements, and budget. If a strategy is unaffordable, then capability trade-offs must be made. The budgeteers knew that just opining about strategy would not carry the day for funding. Instead, the Navy needed analysis to show the effectiveness of its programs and the validity of its arguments. As deputy programmer in OPNAV in the early 1980s, Blickstein noted:

I had no relationship with anybody in OP-06 [Plans, Policies and Operations Directorate]. And you’d think, well you’re building a [budget] and they’re in charge of the Maritime Strategy, shouldn’t you guys be talking all the time? The answer is yes, but did the Maritime Strategy have an impact on our programming work? It really didn’t…Historically, there was no relationship between strategists and programmers, but I think it would be a good thing to have.10Dimitry Filipoff, “Irv Blickstein on Programming the POM and Strategizing the Budget | Center for International Maritime Security,” 1980s Maritime Strategy Series (blog), March 26, 2021, https://cimsec.org/irv-blickstein-on-programming-the-pom-and-strategizing-the-budget/.

In June 2015, the Naval Postgraduate School published a report on strategy’s role to drive the Navy’s budget process. The report’s principal findings stated that the “Navy has failed to ensure that strategy and policy priorities drive [budget] development and execution.” Specifically, within OPNAV, the budget process “eclipses strategy” and “is substituted for, and is often equated to, strategy.”11Dr. James A. Russell et al., “Navy Strategy Development: Strategy in the 21st Century,” Naval Research Program (Naval Postgraduate School in support of OPNAV N3/ N5, n.d.), https://news.usni.org/2015/07/24/document-naval-post-graudate-school-study-on-u-s-navy-strategy-development. The report noted that the Integration of Capabilities and Resources Directorate, a directorate that acts essentially as OPNAV’s Chief Financial Officer, “wields most of the intra-bureaucratic authority and power when it comes to the making and implementation of strategy” and that the Operations, Plans, and Strategy Directorate (OPNAV N3/N5), with its strategy staff, does not “play meaningful role in strategy development and execution.” During his tenure as CNO (2015–2019), Admiral John Richardson attempted to change this attitude. His efforts did not succeed.

Currently, there are significant alignment issues among the budget process, strategy development, and long-range planning processes. The budget process focuses on a five-year period and emphasizes the application of quantitative analysis, which is effective for near-term resource decisions. However, with no clear-cut beginning or end to its annual cycle, the budget process dominates all OPNAV planning activities and “tends simply to encourage the continuation of programs already under way” and discourage “the development of fresh new alternatives.”12Commander Gordon G. Riggle, “Looking to the Long Run,” U.S. Naval Institute, September 1980, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1980/september/looking-long-run. The Navy needs to avoid defaulting to budget execution to develop its strategy. All strategies are shaped and informed by available resources, but the budget should serve the strategy—not the other way around.

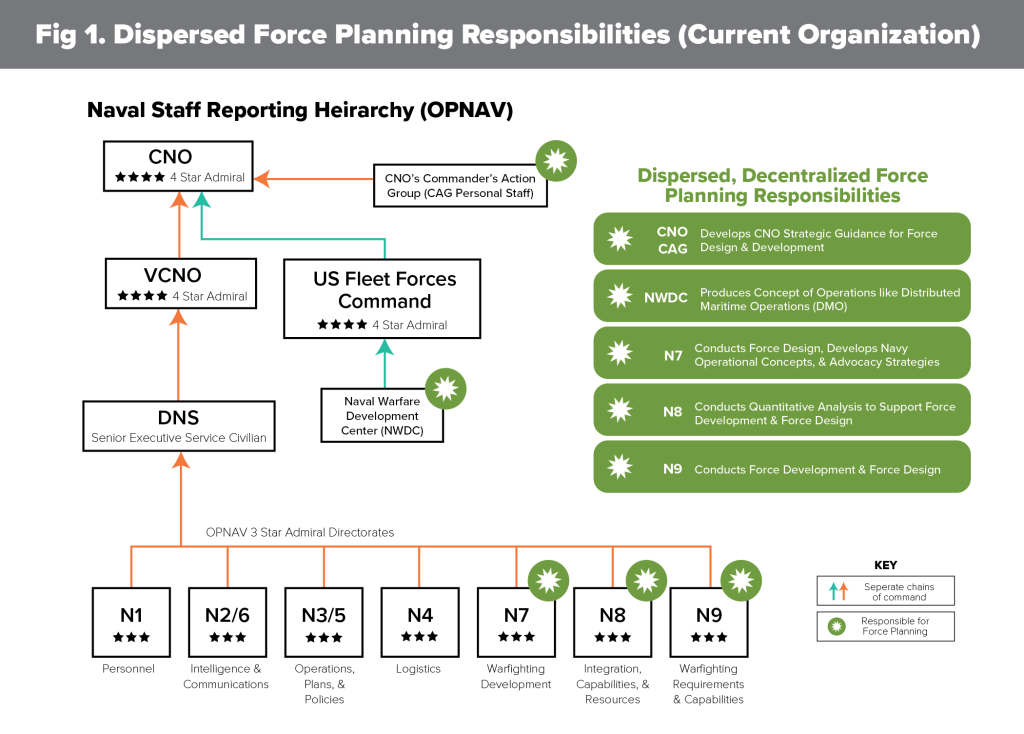

Currently,the responsibility to manage the Navy’s force-planning ecosystem is dispersed throughout OPNAV. The Warfighting Development Directorate (OPNAV N7) addresses force design. The Integration of Capabilities and Resources Directorate (OPNAV N8) addresses the quantitative means to support force design and development, and the Warfighting Requirements and Capabilities Directorate (OPNAV N9) addresses force development and force design. The CNO’s Commanders Action Group provides the terms of reference—strategic guidance—for force design and force development. The Naval Warfare Development Center produces warfighting concepts, such as the current Distributed Maritime Operations (See Figure 1).

Each of these responsibilities must occur, but they are uncoordinated. No directorate integrates these force-planning efforts along with the ongoing production of new ships, aircraft, and weapons to produce a unified Navy fighting machine. As a result, decisions about production of new forces and modernization of in-service forces directly shape decisions about determining future platforms and capabilities, and vice versa. This interrelationship among force development, force design, and the production of new platforms and capabilities demands alignment, integration, and synchronization into a comprehensive process—not as individual platforms and capabilities—along with a shared understanding of the future security environment and a common warfighting concept to deter and defeat future adversaries in specific time periods.

Furthermore, this dispersion of force-planning responsibility has harmful consequences. In February 2022, OPNAV sponsored a workshop, titled the Force Design Sprint, to assess the Navy’s force-design posture. At the conclusion, a senior N7 leader informed the author that the workshop determined, “everyone in OPNAV was in charge [of force design], but no one was in charge.” It was an astonishing discovery for a military service to declare no one in OPNAV actually held responsibility for force design, with its focus on future ships, aircraft, and weapon systems, along with warfighting concepts for the twenty-plus-year time horizon.

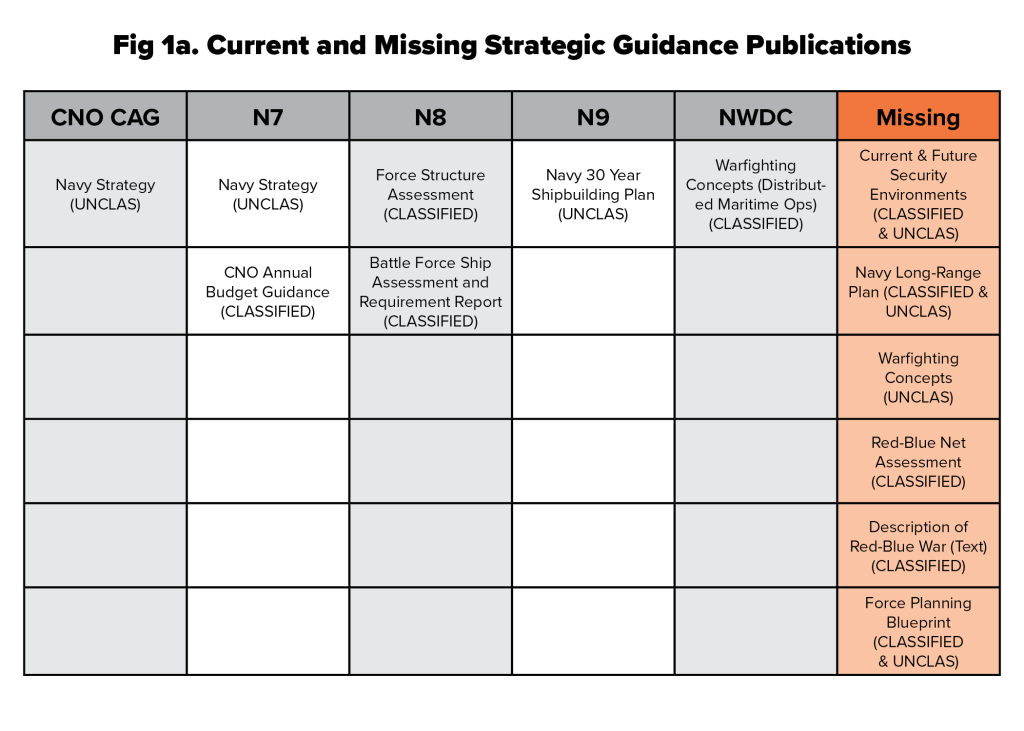

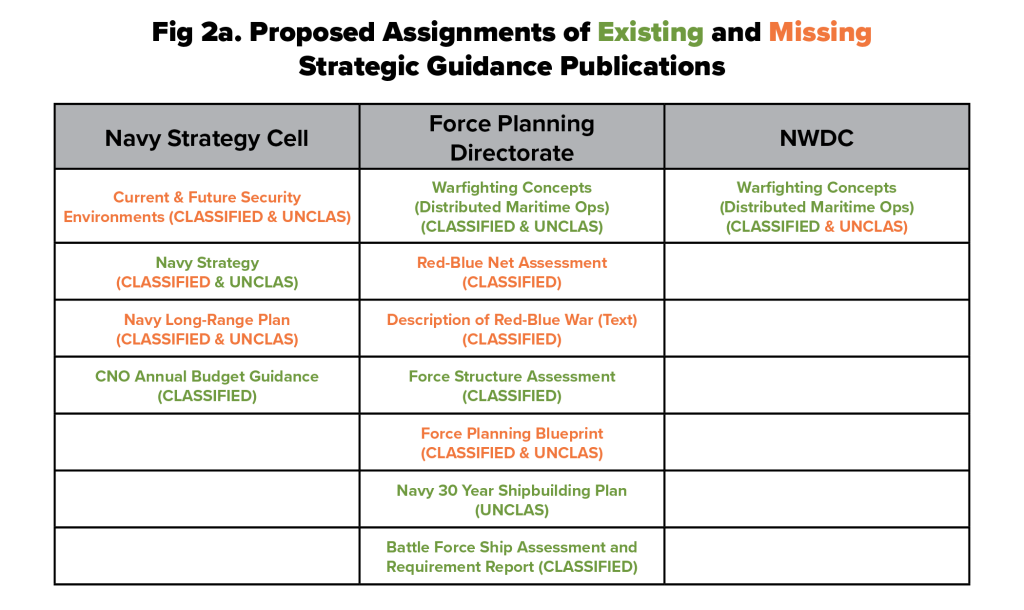

Insufficient strategic guidance misdirects force planning

The Navy lacks sufficient and coherent guidance to ensure strategy shapes its budget and warfighting concepts. It has no classified strategy to facilitate an unambiguous expression of its ends, ways, and means. It has no codified assessment of both the current and future security environments to provide baseline understandings of them and set conditions for effective concept-driven, threat-informed capability development. Another missing document is a warfighting concept for the 2040s timeframe. The result is that, in 2023, specialized N9 staffs are planning the next-generation platforms without the benefit of a common set of capstone strategic guidance. (See Figure 1a)

Navy platform communities distort force planning

Internecine warfare by the Navy’s three platform communities (its surface, aviation, and submarine communities) severely unbalances the Navy as a whole. Expected in theory to rise above their individual platform advocacy and warfare concerns, the communities are all too susceptible to pressures and rivalries from the others. Each warfare community produces an unclassified strategic guidance document with little regard for how the other communities interact and cooperate to generate a unified Navy fighting machine.

Problem definition

In response to this criticism, CNO Admiral Michael Gilday reassigned force-design responsibilities to N7 and focused its efforts on 2045, as outlined in the CNO’s 2022 Navigation Plan.13CNO Admiral Mike Gilday, “Chief of Naval Operations Navigation Plan 2022,” CNO Navigation Plan (US Navy, July 22, 2023). . However, the Navy has largely already decided upon a 2045 force design and, moreover, the Navy is full speed ahead on its implementation. The year 2045 is only about twenty years away, well within the service life for the ongoing production of new ships, aircraft, and weapon systems. CNO Gilday has approved the Navy’s future direction for its next generation of platforms and capabilities, which N9 has developed with the priority order of acquisition as the next-generation aircraft first, the next-generation destroyer second, and the next-generation attack submarine third.14Sam LaGrone, “CNO Gilday: Next-Generation Air Dominance Will Come Ahead of DDG(X) Destroyer,” USNI News, January 18, 2023, https://news.usni.org/2023/01/18/cno-gilday-next-generation-air-dominance-will-come-ahead-of-ddgx-destroyer. This prioritization seems to cement the aircraft carriers as the Navy’s warfighting center of gravity, rather than precision weapons launched from a variety of air, surface, and subsurface platforms.

The long-term problem confronting Navy strategy development and force planning is larger than reassigning force-design responsibility to N7. The Navy needs to address the problem of how it conducts and organizes for strategy development and force planning in toto, not as disparate processes. Based on this paper’s assessment of the Navy’s strategy development and force planning posture, the Navy faces a three-part problem.15A Navy problem statement can either be posed as a question about how to solve an issue or as a negative statement.

- Part one: How does the Navy produce “a force structure, now and in the future, of the right size and the right composition (force mix) to achieve the nation’s security goals, in light of the security environment and resource constraints” and avoid a strategy-force mismatch?16Mackubin Thomas Ownes, “Force Planning: The Crossroads of Strategy and the Political Process – Foreign Policy Research Institute,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, July 1, 2015, https://www.fpri.org/article/2015/07/force-planning-the-crossroads-of-strategy-and-the-political-process/.

- Part two: How does the Navy ensure its strategy—based upon codified current and future assessments of the security environments, along with associated warfighting concepts—drives force-planning decisions in its budget process, and not have those decisions made by default?

- Part three: How does the Navy ensure its force-planning activities include revision of existing warfighting concepts and development of new ones that fully integrate all platforms to produce a single, lethal Navy fighting machine?

Key issues shaping problem solution

Several key issues significantly influence the formulation of recommendations to improve Navy strategy development and force planning.

Organizing OPNAV for effective strategy development

Given the enduring nature of developing, maintaining, updating, and iterating capstone strategic guidance, a dedicated strategy staff (to include responsibility for long-range planning) must have continuity and longevity. Because this guidance is so central to the Navy’s future, their production cannot be an on-again-off-again process. The key is for the CNO to select its director and have confidence in its staff. Once a strategy staff is up and running, the Navy needs to keep it in place. If the CNO is unhappy with its product, he or she should certainly bring in their own selectee to run the show, but the organization itself needs to retain its role, rather than being shoved aside and replaced with a new, favorite staff group.

Avoiding a federated organization to conduct force planning

OPNAV is using a federated organizational construct, which is problematic for conducting force planning. This construct attempts to achieve simultaneously decentralization of responsibilities and unity of effort. It supposedly unites, under a central entity, diverse responsibilities along with distinctive, associated processes, but with the responsibilities still controlled by different and independent entities. It is aspirational and relies on goodwill to meet mission in lieu of a hierarchical structure with authorities to make hard decisions and not focus on achieving consensus. Given the importance of successful force planning to the Navy, the organizing model to follow is a dedicated entity reporting directly to the CNO, such as the Navy Strategic Systems Programs and Naval Nuclear Propulsion, which, respectively, have cradle-to-grave responsibility for sea-launched nuclear-deterrent capabilities and for the Navy’s nuclear propulsion. The Navy needs to borrow a page from these two organizational successes and establish a dedicated, single entity responsible for all matters pertaining to force planning. The CNO’s force-planning responsibilities are so vast in scope, so complex, and so critical, that the Navy cannot disaggregate them across the OPNAV staff or employ a federated construct. It needs to establish a dedicated entity reporting directly to the CNO.

Providing CNO’s direct oversight of force planning and strategy

Only the CNO and the vice chief of naval operations (VCNO), with the authority vested in their offices, can ensure OPNAV maintains a strategic focus. They alone can focus the staff to keep the Navy’s strategic direction front and center, to drive force planning and the budget. The vice admirals who are the deputy chiefs of naval operations leading the seven major functional directorates cannot do it individually; they are challenged enough to meet the urgent demands of the budget process and the press of their daily business.

Understanding defense-analysis limitations to support force planning

Quantifiable defense analysis makes a strong contribution to force planning, especially in the near and middle terms, by understanding trade-offs among platforms and weapons systems. Defense analysis—operations research, campaign analysis, and systems analysis—has restricted relevancy to force planning with its long-range focus of twenty or more years into the future. Defense-analysis methods require certainty of data before they can productively yield reliable certainty in answers. The Navy’s current force-structure assessment methodology, which uses these quantifiable defense analysis tools, will be hard pressed to generate useful data about the long term. Its processes require data for modeling that are simply unavailable twenty years from now—hence, the need for a strong component of risk analysis, wargames, red teams, and alternative-futures work.

Incorporating net assessment capability to support force planning

Force planning requires long-range comparative assessment of trends, key competitions, risks, opportunities, and future prospects of Navy capability. Net assessment provides this comparison of red-blue interaction, using qualitative and quantitative factors across alternative future scenarios. The Navy cannot predict the future with certainty. However, net assessments generate a spectrum of needed capabilities for the Navy to draw upon. The Navy needs this capability because its reliance on campaign analysis, systems analysis, and operations research is grossly unbalanced. The Navy needs to conduct force planning based upon an assessment of the future security environment, and then use tools such as strategic wargames, emulations, expert-panel reports, and net assessment to build a strategy and a warfighting concept, and derive required capabilities. Once that is done, the quantifiable tools can refine the types and number of capabilities.

Clarifying N7 and N9’s force-planning roles

Force planning encompasses force design (i.e., the future fleet) and force development (i.e., the current fleet). CNO Gilday reassigned force-design responsibility from N9 to N7 in July 2022. In reality, N9 will likely continue to conduct force-design responsibility as it determinines the next generation of platforms for operational employment in the 2040s. Given all the approved and funded N9 force-design activity to plan the 2040s Navy, N7’s force planning responsibilities are far from clear.

Incorporating the secretary of the Navy into force planning

Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro has signaled caution and unease with Navy force planning, and wants a realistic approach to understand the total cost and impact of the next-generation destroyer, attack submarine, and crewed/uncrewed aircraft. He wants to test new technologies for these platforms before any production. Given the Navy’s uneven track record in planning and delivering surface ships, along with the issue of affordability to fund an immense recapitalization, his caution is warranted.

Evaluating new technologies and concepts for force planning

The Navy is replacing in-service platforms with newer, follow-on versions, with the exception of uncrewed platforms. This is significant because strong platform attachment may be preventing the Navy from embracing new technologies and warfighting concepts. More importantly, such a possible attitude may prevent the Navy from understanding the changing character of war at sea. For example, because of the convergence of technologies, by 2045 the air and surface domains might become so significantly transparent that, in the competition between the “finder” and the “hider,” the finder might well dominate. If this is correct, surface ships and even aircraft will be increasingly vulnerable to continuous enemy tracking, targeting, and long-range attacks, thereby ending their role—or, at a minimum, severely limiting it—as the principal means of conventional naval power projection. Such an outcome has enormous consequences for the design of a 2045 Navy fleet.

Communicating Navy force-structure requirements

Given the December 2022 establishment of the National Commission on the Future of the Navy and the new reporting requirement for a Battle Force Ship Assessment and Requirement Report in December 2021, the Navy’s strategic-communications capability appears to have had little effect in countering the criticism of its force-planning efforts. The Navy’s strategic communications require an adjustment.

Recommendations

The overarching intent of these recommendations is to link OPNAV’s strategy, analysis, and budget processes. This is a challenge, as the work among the budgeteers, analysts, planners, and strategists is so different. Producing a budget is incremental work that “involves a great deal of analysis and negotiation, over and over again, year after year” and requires “orthodox bureaucratic labor.” Conversely, producing a strategy or a warfighting concept demands “unorthodox leaps of thought—of drawing exceptional inferences from exercises, war games, technology, intelligence, and events.”17Thomas Hone, Private memorandum to author, March 9, 2023.

Historically, with a few notable exceptions, effectively linking these two groups has eluded OPNAV. Consequently, the recommendations address eliminating this gap by consolidating force-planning functions under the direct and strategic oversight of the CNO and VCNO to ensure the linkage between these two groups is maintained. In effect, force planning becomes OPNAV’s center of gravity, with the production of the budget in support.

The logic behind these recommendations is straightforward. The recommendations are governed by an overarching objective to ensure that the Navy’s strategy and policy priorities drive its force planning and budget, not the other way around. The Navy needs to build its forces and capabilities to implement the CNO’s recommended strategy. Force planning begins with that strategy, but the force-planning staff does not create that strategy; the origins of that strategy reside in the CNO’s personal domain, drawing upon higher-level guidance such as the National Defense Strategy. Using the CNO’s strategy, the force-planning staff determines the naval tasks required, and the problems and impediments—such as geography and the adversary’s capabilities—in the current and future security environment that must be surmounted. This activity, in turn, drives the development of warfighting concepts, which leads to the discovery of required naval forces and capabilities and their associated attributes (i.e., operational requirements). Finally, force planning calculates the number and mix of forces and capabilities required to achieve the strategy.18Mackubin Thomas Ownes, “Force Planning: The Crossroads of Strategy and the Political Process – Foreign Policy Research Institute,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, July 1, 2015, https://www.fpri.org/article/2015/07/force-planning-the-crossroads-of-strategy-and-the-political-process/. The following recommendations make this logic a reality.

The eleven primary documents written by the proposed Navy Strategy Cell and the Force Planning Directorate would not be carved in stone and immutable like the Ten Commandants. In the final analysis, they would be the CNO’s documents. Vitally, they would be developed through the active participation of the Navy’s four-star leadership to identify the biggest challenges to the service’s continued relevancy and contribution to national security, and to devise a coherent approach to overcoming them, which the Navy senior leaders would hammer out and support. The purpose of this effort is to define how the Navy will move forward over successive five-year increments of the budget-planning process, with its senior leaders sharing and agreeing to a common approach. It is all about institutionalizing a force-planning process that can endure over decades from first inception to acquisition to initial operational employment, all managed by relatively short-tenured senior leaders.

Obviously, as the threat, budget, technology, and higher-level policy change, the CNO would update these documents on an annual basis, such as the process the Navy employed in the 1930s with at least nineteen major iterations to its War Plan Orange, and in the 1980s with several successive versions of the Maritime Strategy. Full participation of serving four-star and selected three-star admirals in this process will be vital, because, without question, one of these flag officers will become the next or subsequent CNO. If this participation does not occur, the probability for false starts and radical course changes will greatly increase as CNOs change.

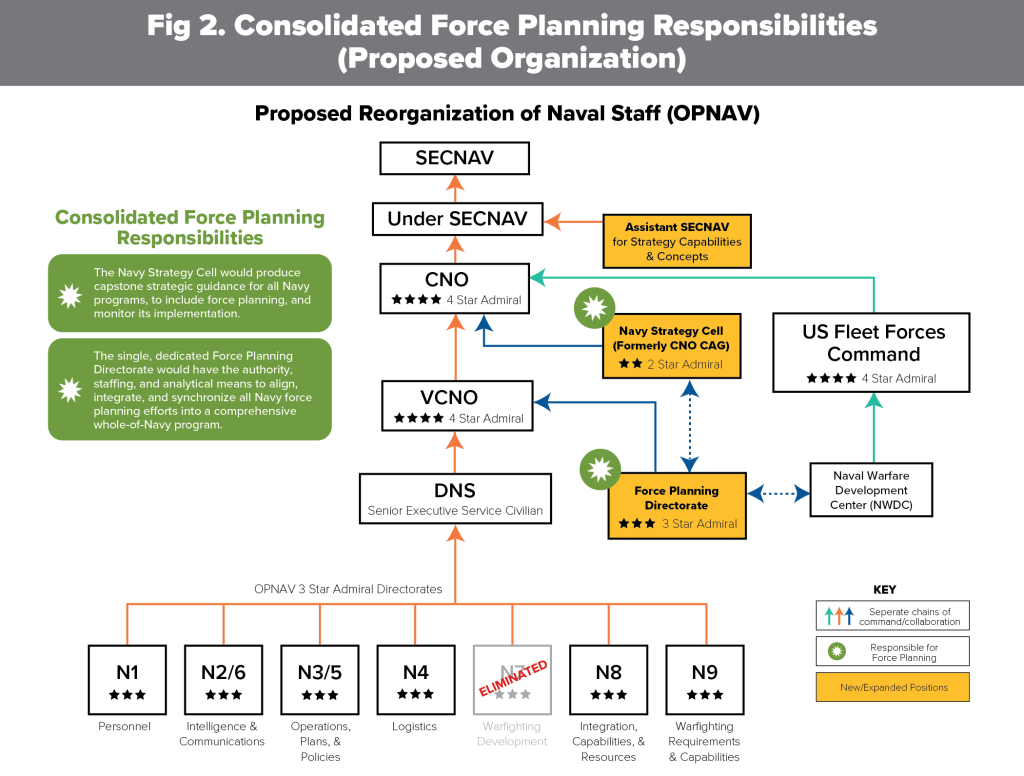

First recommendation: Establish a new Assistant Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy should establish an assistant secretary of the Navy for strategy, concepts, and capabilities (ASN/SC&C) to assist the uniformed Navy (See Figure 2). The standing up of this position would deliver that assistance without needing another management layer. Instead, it offers enormous, impactful benefits by providing the secretary of the Navy the means to ensure:

- Alignment of both Navy and Marine Corps resources, activities, and capabilities with the strategic military objectives and force planning goals of the National Defense Strategy and National Military Strategy;

- Synchronization of Navy and Marine Corps force planning by integrating their efforts at the service-chief level, as well as at developmental level between the Navy’s Naval Warfighting Development Center and the Marine Corps’ Warfighting Laboratory;19The Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory generates and examines threat-informed, operating concepts and capabilities and provides analytically-supported recommendations to inform subsequent force design and development activities.

- The establishment of a strategy-focused counterpart to the assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development, and acquisition (ASN/RDA), and a vital interface with the assistant secretary of defense for strategy, plans and capabilities (ASD/SPC);20Captain Scott Mobley, Retired, “How to Rebalance the Navy’s Strategic Culture | Proceedings – November 2022 Vol. 148/11/1,437,” U.S. Naval Institute, November 2022, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/november/how-rebalance-navys-strategic-culture..

- The development of a single Navy Department strategy, vis à vis the three separate strategies of the department, Navy, and Marine Corps;

- Reform of Navy force-planning activities, reinvigoration of Navy strategic expertise, and the promotion of a strategy-centric culture in both the secretariat and OPNAV; and21Mobley, Retired, “How to Rebalance the Navy’s Strategic Culture | Proceedings – November 2022 Vol. 148/11/1,437.”

- A resolution of protracted issues and problems bedeviling Navy strategy development and force planning.

The final benefit has immense implications, and requires elaboration. The number of issues and problems confronting Navy strategy development and force planning seem almost enduring, foster significant congressional concern, and underscore the compelling need for great secretariat and OPNAV integration. On its own, the Navy has been unable to solve, correct, or mitigate these issues and challenges. Examples of such issues and problems that substantiate the services of a new assistant secretary are as follows.

Increasing affordability of platform

In June 2021, then acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Harker signed a memo addressing Navy funding priorities in its fiscal year 2023 planning cycle to match fiscal guidance from the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

The Navy cannot afford to simultaneously develop the next generation of air, surface, and subsurface platforms and must prioritize these [three] programs, balancing the cost of developing next-generation capabilities against maintaining current capabilities. As part of the budget [program objective memorandum 2023], the Navy should prioritize one of [these three] capabilities and rephase the other two after an assessment of operational, financial, and technical risk.22Megan Eckstein, “Memo Reveals US Navy Must Pick between Future Destroyer, Fighter or Sub for FY23 Plan,” Defense News, June 8, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2021/06/08/memo-navy-will-have-to-pick-between-its-future-destroyer-fighter-and-sub-in-fiscal-2023-planning/.

However, it was not until January 2023 that the Navy explicitly admitted that it could not afford all three major acquisition programs simultaneously, when the Navy announced that the order of acquisition as first is Next Generations Air Dominance (NGADS), then Next-Generation Guided-Missile Destroyer program (DDG(X)), and finally the Next-Generation Attack Submarine program (SSN(X)).23Sam LaGrone, “CNO Gilday: Next-Generation Air Dominance Will Come Ahead of DDG(X) Destroyer,” USNI News, January 18, 2023, https://news.usni.org/2023/01/18/cno-gilday-next-generation-air-dominance-will-come-ahead-of-ddgx-destroyer.

Navy platforms keep getting bigger and more expensive

Strong platform attachment may be preventing the Navy from embracing new technologies and concepts, and consequently replacing in-service platforms with newer, follow-on versions. Navy force planning uses an incremental approach—“buying at the margin [fewer, but] better [and more expensive] versions of the same [type] of platforms [the Navy] has relied upon for decades”—that is delivering an unaffordable fleet over too long a procurement time.24Christian Brose, The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare, First edition. (New York, NY: Hachette Books, Hachette Book Group, 2020).

Proposals for new capabilities can be viewed as threats to in-service platforms, thereby blocking innovation. Quite often, the Navy’s new platforms, weapons, and systems are quite familiar to what is already in the fleet. The DDG(X) is the large surface-combatant replacement for the Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class Aegis destroyers, currently still being procured by the Navy. A November 2022 Congressional Budget Office report on the Navy’s FY-2023 thirty-year shipbuilding plan states, “the Navy has indicated that the initial [DDG(X)] design prescribes a displacement of 13,500 tons,” about 39 percent greater than the 9,700-ton Flight III DDG-51 design.25Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy DDG(X) Next-Generation Destroyer Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” In Focus (Congressional Research Service, March 23, 2023), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11679. There are media reports that actual displacement may be closer to fifteen thousand tons, which would make them comparable to a World War II heavy cruiser.

Technological developments are changing the character of warfare.

The principal means of conventional naval power projection are transforming, and this has enormous consequences for the design of a 2045 Navy fleet. According to US strategist Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr., a disruptive shift is occurring from “precision-warfare regimes” to an emerging one based on “a new military revolution” incorporating “artificial intelligence, additive manufacturing, synthetic biology, and quantum computing, as well as military-driven technologies, including directed energy and hypersonic weapons.”26Captain Gerald G. O’Rourke, USN (Ret.), “Great Operators, Good Administrators, Lousy Planners,” U.S. Naval Institute, August 1984, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1984/august/great-operators-good-administrators-lousy-planners.

Jr Krepinevich, The Origins of Victory: How Disruptive Military Innovation Determines the Fates of Great Powers (New Haven ; Yale University Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300271584, p. 19. Krepinevich cautions that, too often, the US military gets the cart before the horse by fielding capabilities based on new technologies and not addressing “how these new capabilities would maintain their effectiveness” as a technological revolution matured, as was the case with the Navy’s next-generation cruiser.27Jr Krepinevich, The Origins of Victory: How Disruptive Military Innovation Determines the Fates of Great Powers (New Haven ; Yale University Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300271584, p. 19. Unfortunately, as of May 2023, such strategic-planning documents do not exist for the US Navy.

Ineffective strategic communications

The Navy’s poor strategic-communications practices are exemplified by its annual, unclassified thirty-year shipbuilding plan.28Formally titled as the Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year XXXX. The plan fulfilled its purpose, but it was devoid of even a summary of a rigorous, unclassified, analytical rationale to make the case for a larger, more lethal Navy. With that, political leadership could understand the Navy’s defense role and support its claims upon the nation’s resources. It was a missed opportunity to strategically communicate the Navy’s case for resources to one of the Navy’s most important audiences.29Mark Cancian Saxton Adam and Mark Cancian, “The Spectacular & Public Collapse of Navy Force Planning,” Breaking Defense, January 28, 2020, https://breakingdefense.sites.breakingmedia.com/2020/01/the-spectacular-public-collapse-of-navy-force-planning/.As noted, “Planning for a 21st century Navy of unmanned vessels, distributed operations, and great power competition has collapsed. Trapped by a 355-ship force goal, a reduced budget, and a fixed counting methodology, the Navy can’t find a feasible solution to the difficult question of how its forces should be structured. As a result, the Navy postponed announcement of its new force structure assessment (FSA) from January to “the spring.” That means the navy will not be able to influence the 2021 budget year much, forfeiting a major opportunity to reshape the fleet and bring it in line with the national defense strategy.” The Navy does not know how to communicate its force requirements consistently. The best construct for Navy strategic communications is to use platforms. Right now, the Navy is using platform attributes—such as “Ensure Delivery,” which conjures images of Domino’s Pizza or Amazon delivery services—to communicate its requirements to Congress and the American people. Aircraft and ship types are not abstract; they are real things that people can easily visualize when they hear their names—submarine, destroyer, aircraft carrier, and jet fighter, among others.

An a-strategic Navy culture

Strategy is not an institutional Navy value; the service values operational and technocratic expertise above all. Indeed, one telling example illustrates this attitude. Unlike the five other armed services, the Navy does not formally board its selectees to attend the war colleges as students; in effect, the Navy assigns whoever is available. The Navy largely focuses on programming and budget to develop the means for strategy, while “devaluing the strategic underpinnings for rationalizing and justifying those means.30Mark T. Esper, “Chapter 7: The Politics of Building a Better Navy,” in A Sacred Oath: Memoirs of a Secretary of Defense During Extraordinary Times, First edition. (New York, NY: William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2022), p. 200. Captain Scott Mobley, USN (Ret.), “How to Rebalance the Navy’s Strategic Culture | Proceedings – November 2022 Vol. 148/11/1,437,” U.S. Naval Institute, November 2022, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/november/how-rebalance-navys-strategic-culture. Regrettably, the Navy has become, “a technocracy—a technologically centered bureaucracy,” with the CNO and OPNAV staff acting as the “Navy’s lead programmers and budgeters, incentivizing a career system that rewarded officers who acquired the technical skills needed for these roles,” but not incentivizing a career path for strategists.31Captain Scott Mobley, USN (Ret.), “How to Rebalance the Navy’s Strategic Culture | Proceedings – November 2022 Vol. 148/11/1,437,” U.S. Naval Institute, November 2022, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2022/november/how-rebalance-navys-strategic-culture.

A prescient 1984 US Naval Institute Proceedings essay encapsulated the Navy’s astrategic culture: “The finest personal accolade an officer can receive is, ‘He’s a great operator.’”32Captain Gerald G. O’Rourke, USN (Ret.), “Great Operators, Good Administrators, Lousy Planners,” U.S. Naval Institute, August 1984, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1984/august/great-operators-good-administrators-lousy-planners. However, the essay identified a major shortcoming these “great operators” have: they experience, “great difficulty comprehending or even identifying—long-term problems” and are, “convinced that only short-term problems are real, and that continued solutions to each in turn will eliminate or indefinitely postpone the distant ones.”33O’Rourke, USN (Ret.), “Great Operators, Good Administrators, Lousy Planners.” As a consequence of this attitude, the Navy cannot determine a lasting OPNAV organizational structure to ensure its strategy drives its force planning and its budget, in that order. On its own, the Navy cannot sustain its strategy enterprise over the long haul. Underscoring this assessment is the current lack of capstone strategic and force-planning guidance. The Navy does not have:

- A classified version of a combined “2020 Advantage at Sea” and “2022 Navigation Plan” to facilitate a clear and unambiguous expression of Navy ends, ways, and means along with such topics as strategic assumptions, risk, capacity, concepts, and threats;

- A classified assessment of the current and future security environments to provide baseline understandings of operating environments, setting conditions for effective concept-driven, threat-informed capability development;

- A classified warfighting concept for the 2040s timeframe;

- A classified red-blue net assessment at the strategic level;

- A classified description of a red-blue war; and

- A classified Navy long-range plan.

Competition among the Navy platform communities

The internecine warfare between the Navy’s three platform communities (the surface, aviation, and submarine communities) can severely unbalance the Navy as a whole. For example, the aviation tribe focuses on strike from the air; the submarine tribe on strike from the subsurface; the surface tribe on strike from the surface; and the amphibious tribe on strike across the beach. All the while, it is unclear if anyone is asking two fundamental questions: “What are we trying to do? And how can we accomplish this in a far more effective way than we can at present?”34Jr Krepinevich, The Origins of Victory: How Disruptive Military Innovation Determines the Fates of Great Powers (New Haven ; Yale University Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300271584, p. 401. Invariably, there is a competition among tribes for manpower and funding, resulting in disagreements over strategy and the allocation of resources. Reaching consensus among them has always been difficult, and remains a fundamental service chief responsibility.

As defense secretary, Mark T. Esper rejected the Navy’s force plans.

They seemed to be a product of internal Navy logrolling among the various tribes— surface, subsurface, aviation, etc.—to keep their share of the Navy budget largely unchanged. Insiders were confirming this to me.

— Mark T. Esper35Mark T. Esper, “Chapter 7: The Politics of Building a Better Navy,” in A Sacred Oath: Memoirs of a Secretary of Defense During Extraordinary Times, First edition. (New York, NY: William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2022), p. 200.

Esper wanted more attack submarines and a mix of light aircraft carriers (large-deck amphibious ships with F-35B aircraft) for more operational choices and affordability.36Esper, “Chapter 7: The Politics of Building a Better Navy.” He did not want a plan bounded by past warfighting constructs and irrelevant to a future fight with China.37Esper, “Chapter 7: The Politics of Building a Better Navy.” Because the naval-warfare tribes could not give him what he wanted, he directed Deputy Secretary of Defense David Norquist in the spring of 2020 to lead a new force-structure assessment study to maintain naval dominance.

Each warfare community produces an unclassified strategic guidance document—the aviation community has Navy Aviation Vision 2030–2035, the submarine community Commander’s Intent 4.0, and the surface community has Surface Warfare: The Competitive Edge. Each document, for the most part, encompasses community strategy, planning, policy, and vision topics about operations, capabilities, and personnel. There is little in each document about how that community interacts and cooperates with the other two to generate a unified Navy fighting machine. The lack of stated cooperation among the aviation, surface, and submarine-warfare communities in these documents is palpable. The three communities act like a true team of rivals whose intra-service actions have contributed substantively to the establishment of the National Commission on the Future of the Navy.

To resolve these and other such issues and problems challenges, the secretary of the Navy’s role in strategy development and force planning needs to be strengthened by the services of this new assistant secretary.

Second recommendation: Stand up the Navy strategy cell

The CNO should repurpose his Commander’s Action Group as the Navy Strategy Cell to produce the Navy’s capstone strategic guidance and to monitor its implementation by this one, central, and empowered staff entity reporting directly to the CNO (See Figure 2).

All CNOs understand that their most important responsibility as a service chief is to identify the biggest challenges to the Navy’s continued relevancy and contribution to national security, and to devise a coherent approach to overcoming them. This fundamental role serves as the basis for this recommendation. A 2010 Center for Naval Analyses report bluntly stated that developing and implementing such guidance “for the Navy is the CNO’s number 1 job.”38Peter M. Swartz, William Rosenau, and Hannah Kates, “The Origins and Development of A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (2015),” 136 (Center for Naval Analyses, September 18, 2017), https://www.cna.org/reports/2017/origins-and-development-of-cooperative-strategy. Indeed, from what many senior OPNAV veterans have privately communicated to the author, if this responsibility is not “totally owned by CNO,” OPNAV has no strategic focus. They believe the CNO most important responsibility is identifying the biggest challenges to the Navy’s continued relevancy and contribution to national security, and devising a coherent approach to overcoming them.

Already working directly for the CNO, the Commander’s Action Group produces strategic documents such as the annual posture statements, congressional testimony, keynote speeches, and the 2022 Navigation Plan. Building upon this foundation, the proposed Navy Strategy Cell would be uniquely positioned to describe preferred outcomes for the whole Navy. OPNAV’s seven directorates, on the other hand, tend to focus on the outcomes of individual supporting programs. With expansion, empowerment, and augmentation, the Navy Strategy Cell would:

- Enable the CNO to break away from the budget and programming processes that dominate so much of OPNAV’s time and thinking, and increase his or her focus on realistic and effective strategies and concepts for fighting at and from the sea;

- Strengthen the CNO’s ability to align and coordinate the activities of Navy organizations; communicate with a single Navy voice to external and internal audiences; and assess Navy policies, budgets, plans, and programs, and the resultant allocation of scarce resources; and

- Ensure capstone strategic documents reflect a consistent and aligned set of principles, concepts, and tenets regarding the Navy’s fundamental role in implementing national policy, as well as the CNO’s direction.

This recommendation mirrors what most corporate chief executive officers do, which is to make their capstone strategy functions a direct report to the chief executive officer. Consequently, this is no longer a lead role for N3/N5. Every CNO requires the direct support of a staff to provide a coherent, contemporary, authoritative body of Navy strategic thinking—comprehensive in scope—that they can use to help conceptualize, develop, coordinate, maintain, communicate, refine, and assess their thinking. The CNO needs to be optimally assisted and supported by a small, dedicated strategy staff, which is a corporate best practice. The production of capstone strategic guidance and other strategic documents requires a close relationship and physical proximity to the CNO, with no interlocutors. It is a one-on-one relationship between the CNO and, in effect, their “chief strategist” residing in the Navy Strategy Cell. The one-on-one relationship is needed to:

- Implement explicit CNO guidance, not guidance altered by OPNAV directorate agendas;

- Provide unfiltered advice, especially alternative views to CNO; and

- Do it quickly and with a minimum of interference from others.

Capstone strategic guidance describes how CNO intends to overcome “the biggest challenges to the Navy’s continued relevancy and contribution to national security”39Rumelt, Richard P. Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters. Crown Publishing Group, Random House. New York. 2011. across different timeframes and security environments. These documents require significant CNO involvement, visibility, and signature. They provide overarching direction to the service for planning, programming, and budgeting future forces, force planning, and operational employment, and convey fundamental principles about the application of naval power to achieve national policy goals. They drive all subordinate force-planning efforts and connect the Navy’s annual budget submissions and investment plans with the Navy’s key priorities. These documents are truly primus inter pares. They are consequential and substantive, must be derived from national and joint policy and strategy, and reflect a comprehensive, global view informed by the Navy’s current and future capabilities. The Navy Strategy Cell would draft for the CNO’s signature classified and unclassified versions of these four documents that comprise the Navy’s capstone strategic guidance (i.e., its “crown jewels”).

- Assessments of Current and Future Security Environments (classified and unclassified versions do not currently exist).

- The Navy Strategy (classified version does not currently exist).

- Navy Long-Range Plan (classified and unclassified versions do not currently exist).

- CNO’s Annual Budget Guidance (classified).

Third recommendation: Stand up the force-planning directorate

The CNO should consolidate all OPNAV force-planning responsibilities into a new Force-Planning Directorate under a vice admiral reporting to the VCNO and disestablish N7 (See Figure 2).

The unprecedented wakeup call from Congress, when it established an independent National Commission on the Future of the Navy, is sufficient reason to consolidate Navy force-planning efforts under one roof and reform them.

The Navy’s current federated organizational construct to force planning is ineffective. It is unclear in 2023 what OPNAV staff element acts as the central entity to coordinate all OPNAV force-planning efforts conducted by decentralized and independent staff elements. The functions of force planning are expansive, complex, and critical, as Congress just reminded the Navy. In recognition of the weakness of the federated approach, the Navy should follow its own successful examples of non-federated entities reporting directly to the CNO—the Strategic Systems Programs and Naval Nuclear Propulsion—and consolidate all matters pertaining to force planning into a new and dedicated single entity.

This single, dedicated Force-Planning Directorate would have the authority, staffing, and analytical means, to align, integrate, and synchronize the force-planning efforts into a comprehensive whole-of-Navy strategic plan. The relationship among force development and force design, as well their connection to the production of new ships, aircraft, and weapons systems, demands alignment, integration, and synchronization into a comprehensive force-planning blueprint.

This Force-Planning Directorate would have the authority, personnel, and analytical means to align, integrate, and synchronize all force-planning efforts to produce a Navy fighting machine. The new directorate would assess and integrate the future operational environment, emerging threats, and technologies to develop and deliver concepts, requirements, and future force designs, and support delivery of modernization solutions. Most importantly, it would position the Navy for the future by setting strategic direction, integrating the Navy’s future force-modernization enterprise, aligning resources to priorities, and maintaining accountability for modernization solutions.

The budget dominates all OPNAV activities. The only way to guarantee the budget supports and serves the needs of Navy strategy and force planning is to ensure the CNO or VCNO has direct oversight via a dedicated senior leader who has no other writ. The director of the new Force-Planning Directorate should report to the CNO via the VCNO. A Force-Planning Directorate addressing force design with its long-range time horizons and long-range results will not survive in an environment dominated by short-term results unless OPNAV clearly understands that the Force-Planning Directorate is working directly for the CNO, and that the OPNAV directorates have a supporting relationship to this new staff. As the Navy historical record documents, anything less than a direct report will repeat OPNAV’s past mistakes and failed attempts.

The Force-Planning Directorate would draft for the CNO’s signature classified and unclassified version of these seven documents.

- Warfighting concepts (current and future): Classified and unclassified versions do not exist for the 2045 timeframe. A classified version for the current timeframe exists (i.e., distributed maritime operations), but not an unclassified version. The Naval Warfare Development Center would support the development of these service-level concepts.

- Red-blue net assessment: Classified and unclassified versions do not currently exist.

- Description of a red-blue war (current and future): Classified and unclassified versions do not currently exist.

- Force Structure Assessment: Unclassified versions do not currently exist. The June 2023 Battle Force Ship Assessment and Requirement Report will provide a classified version.

- Navy force planning blueprint (current and future): Classified and unclassified versions do not currently exist.

- Thirty-year shipbuilding plan: An unclassified version exists.

- Battle force ship assessment and requirement report: A classified version exists. The June 2023 version of this report could potentially serve as a classified Force Structure Assessment.

The Warfighting Concepts would establish a baseline understanding to set conditions for effective concept-driven, threat-informed force planning, in order to produce a Navy Force Planning Blueprint. It would be based on a common understanding of the current and future security environments and a shared articulation of how the Navy fights as a whole, and not merely as a collection of individual classes of platforms. It would be the Navy’s comprehensive plan—not a strategy—to integrate, align, and synchronize all its force-planning efforts, including the efforts of force development and force planning along with the ongoing production of new ships, aircraft, and weapons systems to produce the Navy fighting machine (i.e., a unified combination of air, surface, and subsurface Navy lethality). Figure 2a depicts the consolidated production of the Navy’s eleven key strategic guidance documents from numerous OPNAV organizational elements to just two.

Establishment of this new Force-Planning Directorate topples the budget process as OPNAV’s dominant process. Force planning would become OPNAV’s center of gravity, with the budget in support, and no longer the other way around. It turns over the proverbial apple cart, with force planning reporting directly to the CNO and leading a strategic-centric staff dialogue, as opposed to a budget-centric dialogue. This reversal will generate strong resistance from N8 and N9 in particular. Because the Force Planning Directorate will be the primus inter pares, and as the other OPNAV directorates are all headed by a vice admiral, the new Force-Planning Directorate must likewise be headed by a vice admiral or else be doomed to failure.

This new Force-Planning Directorate requires the capability to conduct Navy net assessments for strategic analysis of red-blue interactions for informed and realistic plans. Net assessments (along with defense analysis) are diagnostic means, whereas force planning is a prescriptive means. The two belong together; if not, dysfunction will continue to hamstring efforts. This capability does not currently exist in OPNAV, and would require new personnel resources.

Resourcing the recommendations

The resources to make these recommendations real are readily available; it is just a matter of resetting priorities. The Navy is under heavy congressional fire for its strategy-development and force-planning efforts. Correcting this situation for the long term is surely one of the Navy’s highest priorities.

Given these circumstances, can the Navy say, for example, that the large number of officers assigned to the front office of its three-star leaders is more important than staffing its capability for strategy development and force planning? Again, it is a matter of priorities. If staffing these front offices is more important than retrieving control of force planning from the National Commission on the Future of the Navy, then so be it. It is simply a matter of priorities, and making the tough choices that many leaders say they like to do. Here is another opportunity.

For the reasons presented in this paper, leadership of the Navy Strategy Cell and Force-Planning Directorate requires senior flag officers. Disestablishing the N7 directorate would provide the vice admiral billet to lead the Force-Planning Directorate and a rear admiral billet to head the Navy Strategy Cell. The majority of N7’s functions can return to OPNAV N3/N5 and a portion of N7’s functions can relocate to staff the Navy Strategy Cell and the Force-Planning Directorate.

While there are no perfect organizational frameworks, there are organizational frameworks that better align a greater number of common functions, as outlined in these recommendations. A strategy office reporting to the corporate chief executive officer—in the Navy’s case, the CNO—is a proven practice, and a direct-report senior leader responsible for all Navy force planning is no different than having the Naval Nuclear Propulsion and Nuclear Weapons Program/Strategic Systems Programs as direct reports.

The emphasis of the proposals in this white paper is on strategy-development and force-planning reinvigoration and reasonable consolidation of similar functions, given the centrality of Navy strategy and force planning to all other OPNAV responsibilities. Force planning, if done properly with strategy in the lead and with its capstone strategic-guidance documents, will generate enormous benefits.

Conclusion

Congress has lost patience and confidence in the Navy. There is no way to sugarcoat this action. It is nothing less than a strong condemnation of the Navy’s approach to strategy development and force planning. When US Representative Rob Wittman (R-VA) in December 2022 penned his scathing commentary in Defense News, he was on target in stating, “if the Navy refuses to learn lessons from this year, it will be doomed to repeat them.”40Rob Rep. Wittman, [R-VA-1], “Congress Is Building a Stronger Fleet than the Navy,” Defense News, December 1, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2022/12/15/congress-is-building-a-stronger-fleet-than-the-navy/.

The warning signs have been evident for years. However, much like the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance’s stubborn, twenty-one-month resistance in World War II to correct three major defects of the Mark 14 torpedo, the Navy since the end of the Cold War has neglected its strategy enterprise and resisted effective force planning.41Clay Blair, Silent Victory: The U.s. Submarine War Against Japan., 1st edition (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1975). It has repeatedly failed to understand and act on the mismatch between OPNAV’s robust organization for building the budget and its ineffective organization for developing and implementing Navy strategy.

The Navy needs to think and act like it did in the 1920s and 1930s, when it prepared to confront the Imperial Japanese Navy. The US Navy’s strategy, future security environment, and warfighting concept were all reflected in nineteen iterations to its War Plan Orange and updates to the Rainbow series of war plans. The Naval War College focused its curriculum and wargames throughout the 1930s on defeating the Imperial Japanese Navy, and almost every Navy flag officer was a war-college graduate. While far from perfect, the Navy of the past shared a common view of what a war with Imperial Japan entailed and clearly understood logistics were a top-tier priority for warfare across the vast distances of the Pacific. Likewise, in 2023, the Navy needs the same level of focus and preparation as its predecessor, and the proposed Navy Strategy Cell and Force Planning Directorate will help ensure it is ready for whatever lies ahead.

The author would like to be more of an optimist than a realist, but the Navy continues to allow mistakes to go uncorrected decade after decade. It is, like Winston Churchill stated, a “long dismal catalogue of the fruitlessness of experience and the confirmed unteachability of mankind.”42Robert Kagan, The Ghost at the Feast: America and the Collapse of World Order, 1900-1941, First edition. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023), p. 468. It is foolish to believe that the Navy will change on its own to conduct more effective strategy development and force planning.43Leonard Dr. Wong and Stephen Dr. Gerras, “Changing Minds In The Army: Why It Is So Difficult and What To Do About It,” Monographs, Collaborative Studies, & IRPs, October 1, 2013, 48, p. 20. The only way the Navy will change is for Congress to direct it, or else the Navy will continue with its flawed ways.

About the author

As a member of the Senior Executive Service for the Department of the Navy, Bruce Stubbs served on the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) staff from June 2011 to September 2022 as the Director of Strategy and Strategic Concepts (OPNAV N7), the Director of Strategy (OPNAV N3/5), and the Deputy Director of Strategy and Policy (OPNAV N3/5). Prior to those assignments, he served on the Secretary of the Navy’s immediate staff from June 2008 to May 2011 with responsibility for the coordination and implementation of Maritime Domain Awareness programs, policies, and related issues across the Defense Department.

Forward Defense, housed within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, generates ideas and connects stakeholders in the defense ecosystem to promote an enduring military advantage for the United States, its allies, and partners. Our work identifies the defense strategies, capabilities, and resources the United States needs to deter and, if necessary, prevail in future conflict.

Image: The aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73) is seen underway in the Pacific Ocean Sept. 8, 2012. George Washington is the centerpiece of Carrier Strike Group Five, the only continuously forward deployed carrier strike group in the U.S. Navy. (DoD photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Paul Kelly, U.S. Navy/ Released)