Italy’s policy on China: The Belt and Road gamble and its aftermath

This is the sixth chapter of the report “Is Europe waking up to the China challenge? How geopolitics are reshaping EU and transatlantic strategy.” Read the full report here.

Italy’s relationship with China is among the oldest in Europe, dating back to the Middle Ages, when Marco Polo and other Venetian merchants traveled east along trade routes that would later be known as the Silk Road. Modern engagement resumed when Rome recognized the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1970—ahead of many other Western nations—reflecting Italy’s ambition to diversify its foreign policy, serve as a bridge between East and West, and expand economic opportunities.1Seamus Taggart, “Italian Relations with China 1978–1992: The Long Carnival Decade—Burgeoning Trade and Diplomatic Kudos,” Cahiers de la Méditerranée 88 (2014), 113–134, https://journals.openedition.org/cdlm/7512. Economic ties grew steadily after China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), culminating in a comprehensive strategic partnership by 2004.

Until recently, the Sino-Italian relationship fluctuated considerably. Successive Italian governments, facing economic stagnation, viewed engagement with China as a potential lifeline for growth, which culminated in Italy’s decision to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2019. Yet a coherent and sustainable trade policy never fully materialized, constrained by Italian political volatility, global crises, and the hardening of China’s internal politics. The early promise of cooperation was repeatedly undermined by events such as the 2008 global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Beijing’s support for Russia in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine.

Under Prime Minister Mario Draghi, Italy reassessed its China policy, aligning more closely with European and transatlantic partners. Since the election of Giorgia Meloni in 2022, Italy has moved from BRI-era optimism to pragmatic realignment with the West. Rome now combines transatlanticist loyalty with economic caution, strengthening controls and formally exiting the BRI. Anchored in EU and NATO frameworks, the country pursues a measured and resilient approach that balances EU de-risking with national pragmatism, while acknowledging Beijing’s human rights violations and its support for Russia. Central to this approach has been a vocal commitment to the importance of transatlantic alliances and values.

Trade and investment: Made in Italy vs. Made in China

Sino-Italian economic ties expanded significantly from the late 1970s, accelerating after China joined the WTO. Italian exports emphasized high-quality manufacturing, while imports were dominated by low-cost goods, reflecting China’s rise as a global manufacturing hub and Italy’s comparative strength in design and high-value products. In 2004, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao elevated the bilateral relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership, broadening cooperation in trade, investment, energy, culture, and politics.2Nicola Casarini and Marco Sanfilippo, “Italy and China: Investing in Each Other,” in Mikko Huotari, et al., eds., “Mapping Europe–China Relations: A Bottom-Up Approach,” Mercator Institute for China Studies, October 2015, 46–50, https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/2015_etnc_report.pdf.

By 2007, China had become one of Italy’s top trading partners, with trade rising more than sevenfold, from $9.6 billion in 2001 to $70.3 billion by 2024.3“Italy Imports from China,” Trading Economics, last visited October 10, 2025, https://tradingeconomics.com/italy/imports/china. In the mid-2010s, Rome, seeking capital and export opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), deepened ties with China, drawing inspiration from the United Kingdom’s “golden era”.4The Conservative–Liberal coalition (2010–2015) pursued a liberal, finance-driven approach to China, laying the groundwork for the so-called “golden era” in bilateral relations. Coined around Xi Jinping’s 2015 state visit, the term reflected the David Cameron government’s effort to deepen engagement and attract Chinese investment in finance and infrastructure. William Matthews, “What the UK Must Get Right in Its China Strategy: Resilience, Flexibility and Autonomy as Core Principles for Engagement,” Chatham House, July 2025, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2025-07/2025-07-08-uk-china-strategy-matthews.pdf. Prime Minister Matteo Renzi’s 2014 visit to Beijing produced the 2014-2016 Action Plan for Economic Cooperation and memorandums of understanding (MoUs) in key sectors, followed by high-level exchanges, including President Sergio Mattarella’s 2017 state visit and Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni’s participation in the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. Optimism for closer ties grew in Italy, but the global context shifted dramatically by late 2017, with the first Trump administration’s confrontational stance toward China, Xi Jinping’s assertive 19th Communist Party Congress, and the onset of a US-China trade war in 2018.

Italy’s 2019 entry into the BRI was intended to boost “Made in Italy” exports. Trade, however, grew unevenly: Chinese exports to Italy jumped 50 percent, from $35 billion to $66 billion, while Italian exports to China rose only modestly, from $14.5 billion to $17 billion. Imports later fell amid the war in Ukraine, shifting geopolitical dynamics, and Italy’s withdrawal from the BRI. Despite these developments, the trade deficit reached $37 billion in 2024. These figures also include Italian exports to China routed through Germany as part of European supply chains.

Today, Italy’s exports to China—roughly $17 billion—pale in comparison to more than $54 billion in Chinese exports to Italy, making China the country’s third-largest import partner. While Italy is flooded with Chinese products (the PRC accounts for 8.8 percent of imports, second only to Germany), exports to China account for only 2.5 percent of Italy’s total exports, far below Germany (12 percent), the United States (11 percent), or France (10 percent).5“Italy Exports by Country,” Trading Economics, last visited October 10, 2025, https://tradingeconomics.com/italy/exports-by-country. Italian products make up just 1.1 percent of China’s total imports.6“China Imports by Country,” Trading Economics, last visited October 10, 2025, https://tradingeconomics.com/china/imports-by-country.

Chinese investments in Italy surged in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, with Chinese entities quick to capitalize on vulnerable Italian firms. From a negligible $5 million in 2008, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows rose to $100 million in 2010 and continued climbing, reaching $4.3 billion by 2024. Cumulatively, according to the Mercator Institute for China Studies,7Agatha Kratz, et al., “Chinese Investment Rebounds Despite Growing Frictions—Chinese FDI in Europe: 2024 Update,” Mercator Institute for China Studies and Rhodium Group, May 21, 2025, https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-investment-rebounds-despite-growing-frictions-chinese-fdi-europe-2024-update. Chinese investment totaled $18 billion (€15 billion), making Italy the EU’s fourth-largest recipient after Germany, France, and the Netherlands. The American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker estimates the broader figure—including contracts and loans—at more than $24 billion in 2025, concentrated in transport ($8.7 billion), energy ($6.5 billion), and technology ($5.3 billion).8“China Global Investment Tracker,” American Enterprise Institute, last visited October 9, 2025, https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/. Major deals include ChemChina’s $8 billion acquisition of a 17 percent stake of Pirelli in 2015, and over $4 billion in stock purchases in top Italian companies—including Intesa Sanpaolo, Unicredit, Eni, Enel, Telecom Italia, Generali, and Terna—via the People’s Bank of China. Beijing has shown particular interest in Italy’s financial and insurance sectors, with State Grid of China investing in Cassa Depositi e Prestiti Reti to acquire 35 percent stake ownership and help launch its “Panda” bond program.

BRI membership promised large infrastructure projects, notably at the port of Genoa and through the “Five Ports” initiative, which envisaged Chinese ownership stakes in the ports of Venice, Trieste, and Ravenna, as well as Capodistria (Slovenia) and Fiume (Croatia) under the North Adriatic Port Association (NAPA). Results were mixed: Trieste and Genoa initially expressed interest and signed cooperation agreements with China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) but eventually withdrew in 2023 amid political and administrative hurdles. Now serving as an EU-focused platform for sustainable and digital logistics, NAPA has supported EU and national investments in Trieste, Venice, and Ravenna—signaling the Adriatic strategy’s return to European oversight.9Karin Smit-Jacobs, “Chinese Strategic Interests in European Ports,” Think Tank, European Parliament, February 27, 2023, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_ATA%282023%29739367. Still, targeted investments continued, flowing into the GAC Design Center and a Geely Auto design studio in Milan, as well as China Ocean Shipping Company Limited’s 2024 acquisition of Trasgo, a major Italian logistics firm with an integrated international supply chain company. In 2020, Rome froze several agreements with Chinese state-owned companies due to security concerns, replacing CCCC in Trieste with a German firm and withdrawing from joint space cooperation on the Tiangong-3 space station. Yet Italy’s economic structure complicates security-driven decoupling from China: its SMEs are embedded in German supply chains, and around 60 percent of its regional industries are linked to China through these networks, particularly in the manufacturing and automotive sectors.

Since the mid-2000s, especially after the “bra war”10Until 2005, global textile trade was governed by the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA), but after its expiry on January 1, 2005, China’s low-cost textile exports surged—rising by more than 200 percent in Europe within six months. Italy’s textile industry was among the hardest hit, struggling to withstand the influx of cheap Chinese imports. that devastated textile manufacturers, many Italians have viewed China’s rise as a threat, citing cheap imports, job losses, and Beijing’s industrial policies undermining SMEs, the lifeblood of the Italian economy.11“The EU and China in ‘bra wars’ deal,” The Guardian, September 6, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2005/sep/06/politics.europeanunion. Public opinion has grown more critical of China, fueled by pandemic narratives and Chinese acquisitions linked to business closures. Tensions over values add another layer of friction: although Italian leaders rarely press China on human rights—a practice fairly common in Europe—public sympathy for Tibet and concerns about human rights violations have fueled negative perceptions.

Mask diplomacy and Italy’s BRI misstep

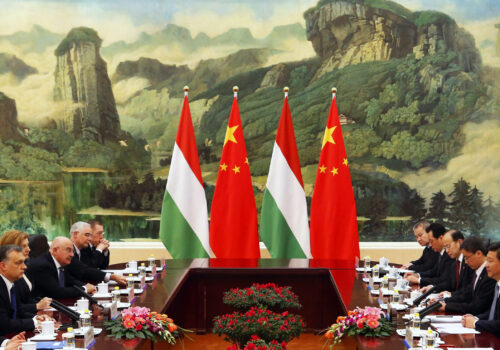

In March 2019, the signing of an MoU on the BRI during Xi Jinping’s state visit to Rome and Palermo proved controversial. The MoU, covering fifty agreements in economic, cultural, and infrastructural areas, made Italy the first G7 member—and the largest EU country—to join the BRI. Though legally non-binding, it was a major geopolitical win for Beijing and raised alarm in Brussels and Washington for breaking transatlantic unity. Strategically, Italy’s membership was crucial to China’s Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road.

The BRI deal, signed under the 2018-2019 Giuseppe Conte government—a coalition of the Five Star Movement and Lega—aimed at short-term gains but misread the broader strategic context. Ironically, it was finalized just one day after the European Council adopted a sharper China strategy, framing the PRC as a threefold challenge: negotiating partner, economic competitor, and systemic rival. Rome hoped the MoU would boost trade and attract investment to offset sluggish growth and mounting debt, with expectations of Chinese financing for infrastructure.

Before any traction was gained, however, the COVID-19 pandemic flipped the dynamic.12Valbona Zeneli and Federica Santoro, “COVID 19 Pandemic and How It Affected Sino Italian Relations,” Orbis, Foreign Policy Research Institute, July 12, 2023, https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/07/covid-19-pandemic-and-how-it-affected-sino-italian-relations/. Italy, one of Europe’s hardest-hit countries, became the focus of what was later called China’s “mask diplomacy”—Beijing’s effort to bolster its image as a responsible global power and shape the narrative around the pandemic. While Italy did purchase planeloads of masks and medical supplies from China, Beijing deliberately distorted the nature of this exchange through media, diaspora networks, and disinformation channels, portraying itself as Italy’s rescuer while casting the EU as absent. Italian intelligence and parliamentary reports later confirmed the coordinated nature of these influence and disinformation efforts, highlighting how China, alongside Russia, sought to manipulate Italy’s domestic discourse and weaken European cohesion. By late 2020, public opinion shifted, with 62 percent of Italians holding a negative view of China and seeing the pandemic-aid narrative as political manipulation. Chinese disinformation campaigns undermined the Italian government’s enthusiasm toward Beijing. Amid this growing skepticism—and increasing supply chain vulnerabilities—the second Conte government (2019-2021) began reassessing Italy’s BRI membership.

In 2021, Mario Draghi’s technocratic government accelerated this policy shift, strengthening the so-called “golden power” rules, tightening scrutiny of Chinese investment, and aligning more firmly with transatlantic partners. Meloni’s election in 2022 reinforced this course. Calling BRI membership a mistake, she blocked ChemChina’s bid for control of Italy’s iconic tire maker Pirelli in June 2023—and in December of the same year she opted not to renew the BRI deal. Still, Italy diplomatically reaffirmed its economic ties with China under the broad “strategic partnership,” first signed in 2004 and renewed in 2014 and 2024.13Valbona Zeneli, “Italy’s ‘Arrivederci’ to China’s BRI Could Be a Template for Others,” Atlantic Council, December 11, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/italys-arrivederci-to-chinas-bri-could-be-a-template-for-others/. Its BRI-exit did not trigger Chinese retaliation, but it dismantled key symbols of Beijing’s influence, realigning Rome with the EU’s de-risking strategy.

Technology: Pivoting to a “buy transatlantic” strategy

Chinese investment in Italy’s tech sector has focused on acquiring manufacturing know-how, expertise, and established brands in specialized manufacturing clusters. Essentially, it aims to move into higher-value products by building on—and at times blatantly copying—Italy’s strengths in industrial design and branding.14Carlo Pietrobelli, Roberta Rabellotti, and Marco Sanfilippo, “Chinese FDI Strategy in Italy: The ‘Marco Polo’ Effect,” International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation and Development 4, 4 (2011), 277–291, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264821612_Chinese_FDI_strategy_in_Italy_The_%27Marco_Polo%27_effect. The Conte government exacerbated Italy’s risky ties with China in infrastructure and high tech, including Huawei’s role in 5G. Draghi later sought to reverse course but faced pro-China voices within his coalition. Under Meloni, however, Rome moved to cut dependencies, including plans for a full ban on Chinese information and communication technologies (ICT).

During the first Trump administration, Huawei was branded a security threat, with the United States pressing allies to exclude the company from their 5G networks as part of a broader campaign of “de-coupling” from China in critical technologies, including semiconductors and artificial intelligence (AI). Italy, like several other EU states, opted for tighter vetting rather than an outright ban. By 2021, Huawei’s role in European networks had already begun to shrink. Italy’s “golden powers” framework, introduced in 2012, gave the government authority to block or condition foreign takeovers in strategic sectors.15“Golden Power: The Italian Government’s Powers over Companies of Strategic Importance,” Rödl & Partner, May 10, 2024, https://www.roedl.com/insights/italien/golden-power-italian-government-powers-companies-strategic-importance. Initially limited to defense and security, it was expanded in 2017 to energy, transport, and communications.

After parliamentary calls in 2019 to “very seriously” consider banning Huawei, Conte resisted but agreed to expand oversight under “golden power” rules.16Daniele Lepido, “Italian Lawmakers Urge Government to Consider Huawei 5G Ban,” Bloomberg, December 20, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-12-20/italian-lawmakers-urge-government-to-consider-huawei-5g-ban. Under US pressure, the framework was eventually expanded in 2020 to cover 5G, finance, health, AI, and media. During Draghi’s term, it became one of Europe’s broadest and most closely coordinated measures for blocking Chinese acquisitions in high-tech industries, complementing the EU’s new FDI screening mechanism.17The “golden power” instrument has been used to prevent three Chinese takeovers, and undo one takeover that had been concluded during the previous government. These actions started with the blocking of the Chinese Shenzhen Investment Holdings from acquiring the Italian semiconductor enterprise LPE (specializing in epitaxy reactors). The prospective buyer had ties with the Chinese arms industry. The Italian government has blocked a Chinese robot maker’s 2-million euro investment in a domestic robotics company under the country’s “golden power law” for sensitive industries. Meloni further reinforced the “golden power” rules in 2023, restricting ChemChina’s influence over Pirelli and curbing Huawei and ZTE in the telecommunications sector. Huawei’s share in Italy’s 5G infrastructure has since fallen from over 50 percent in 2019 to about 35 percent in 2024.18“Is There a Correlation between European Nations’ Level of Chinese Telecom Equipment, the Consumption of Russian Energy, and Military Aid to Ukraine?” Strand Consult, March 18, 2025, https://strandconsult.dk/is-there-a-correlation-between-european-nations-level-of-chinese-telecom-equipment-the-consumption-of-russian-energy-and-military-aid-to-ukraine/. Yet dependence remains, as Huawei and ZTE built much of Italy’s 4G network.19In 2020, the Italian government reviewed seventeen telecom-related cases; Huawei’s bid to supply Fastweb’s core 5G equipment was blocked, while the other sixteen proceeded under special conditions and monitoring. Today, the “golden power” framework has become central to Italy’s broader de-risking strategy. In May 2025, Italy adopted a “Buy Transatlantic” law, prioritizing procurement from Italy, the EU, NATO, and allied partners to secure ICT and cybersecurity supply chains. The law goes beyond the EU’s “Buy European” policy and the United States’ “Buy American Act,” fostering a transatlantic zone of trusted suppliers and potentially serving as a model for defense procurement.

Security: Chinese diaspora networks and covert activities

Italy’s view of China has shifted from economic optimism to strategic caution, with heightened concerns about security, covert influence, and geo-economic risks. Rome’s 2019 BRI decision alarmed both the United States and the EU, while at home, politicians and security experts warned about Chinese investment in strategic sectors and the implications for Italy’s Western alignment.

Chinese information operations, which intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic alongside Russian propaganda, aimed to undermine democratic debate, promote pro-China narratives, stoke anti-EU “Italexit” sentiment, and weaken societal cohesion.20Zeneli and Santoro, “COVID 19 Pandemic and How It Affected Sino Italian Relations.” Beijing also mobilized its diaspora network in Italy, one of the largest in Europe, with 309,000 people, including 50,000 students, blurring humanitarian engagement with influence operations.21“ISTAT. Popolazione Residente e Dinamica Della Popolazione,” POP.ACLI, January 8, 2025, https://pop.acli.it/rubriche/post-it/759-istat-popolazione-residente-e-dinamica-della-popolazione. A report by the Italian parliamentary intelligence oversight committee confirmed these efforts, prompting Italy to strengthen counter-hybrid measures and align more closely with NATO and EU security frameworks to reinforce its transatlantic posture.22Gabriele Carrer, “Hybrid Threats from Russia and China: Italy under Siege,” Decode39, March 4, 2025, https://decode39.com/10078/hybrid-threats-from-russia-and-china-italy-under-siege/.

Amid broader concerns about Chinese influence operations,23Gabriele Carrer, “Chinese ‘Police Stations’ in Italy under US Scrutiny,” Decode39, April 3, 2025, https://decode39.com/10078/hybrid-threats-from-russia-and-china-italy-under-siege/. reports of unofficial Chinese “police stations” in Italy—used to monitor the Chinese population abroad and force dissidents to return—drew scrutiny. Academic ties have also raised alarms: since the early 2000s, over one thousand agreements between sixty-four Italian and Chinese universities have included cooperative in sensitive dual-use fields such as biomedicine, robotics, and semiconductors. New agreements have declined since 2020 and the current government is preparing national research security guidelines to address security risks in research and academia. Still, sixteen Confucius Institutes operate in Italy without clear regulations.

Prime Minister Meloni has long criticized Beijing, denouncing authoritarianism, mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic, human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and threats against Taiwan.24Serena Console, “Come Potrebbe Comportarsi il Governo di Meloni con la Cina,” Today, September 23, 2022, https://www.today.it/politica/governo-meloni-rapporti-cina-taiwan-elezioni-25-settembre.html. While staunchly condemning Russia’s war in Ukraine,25“Meloni si Schiera con Taiwan: ‘Ferma Condanna per l’Inaccettabile Condotta della Cina [Meloni sides with Taiwan. Strong condemnation for the unacceptable behavior of China],” Agenzia Nova, September 23, 2022, https://www.agenzianova.com/news/meloni-si-schiera-con-taiwan-ferma-condanna-per-linaccettabile-condotta-della-cina. she has warned that aggression toward Taiwan could jeopardize China’s access to the EU market. Despite limited public support for military aid to Ukraine (currently at 39 percent), Meloni has firmly backed Ukraine while making NATO solidarity, EU strategic autonomy, de-risking efforts, and close ties with the United States the foundation of her China policy.26“Transatlantic Trends 2022: Public Opinion in Times of Geopolitical Turmoil,” German Marshall Fund of the United States and Bertelsmann Foundation, September 29, 2022, https://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/Transatlantic%20Trends%202022.pdf.

Italy’s alignment with the EU’s China policy

Italy’s stance toward China has shifted toward EU alignment, shaped by external pressures and internal political dynamics. In 2017, Rome joined Berlin and Paris in advocating for an EU investment screening mechanism but abstained from the final vote, reflecting internal political divisions that also contributed to its decision to join the BRI in 2019. Its exit from the initiative in December 2023, coupled with stronger enforcement of “golden power” rules, signaled cross-party skepticism of China and Giorgia Meloni’s commitment to transatlantic cooperation.

China’s support of Russia’s war effort in Ukraine further reinforced Italy’s cautious stance, embedding the country firmly within the EU’s de-risking strategy by balancing economic ties with security vigilance. The discreet BRI withdrawal emphasized continuity through the relaunch of the strategic partnership and was aimed at depoliticizing relations while restoring Western credibility. Italian foreign policy is traditionally reactive and fragmented, driven by short-term economic gains and party politics rather than long-term strategic vision. Therefore, Rome is also less inclined than Brussels to cast China as a rival. Under Meloni, however, Italy has aligned more closely with the United States and the EU on security, adopting a cautious approach to limit Chinese access to strategic sectors.

Conclusion

Italy’s China policy has shifted from BRI-era optimism over economic benefits to a pragmatic need for closer alignment with the EU and the United States. Blending transatlantic loyalty with economic caution is now the guiding principle. Rome has strengthened investment screening, blocked Chinese acquisitions in strategic sectors, and withdrawn from the BRI, while still avoiding overtly confrontational rhetoric to protect its exports. The result is a China policy that is less ideological than the European Commission’s systemic rival framing and less securitized than the United States’ rivalry-driven approach. Nonetheless, Italy’s path reflects growing awareness of the geopolitical and security risks of conducting business with China—especially compared with the value- and security-based partnership it enjoys with the United States and the EU.

The US-China rivalry and Beijing’s alignment with Moscow have considerably hardened Italy’s stance. NATO engagement has reinforced Rome’s cautious security posture, limiting Chinese access to critical infrastructure and technology, while Russia’s war in Ukraine has deepened its resolve against Moscow and reaffirmed its commitment to the EU and NATO security frameworks. In the Indo-Pacific region, Italy participates selectively in deployments, signaling solidarity rather than projecting power, and avoids labeling China a direct security threat, focusing instead on resilience and coordination with transatlantic partners.

Economically, Italy balances EU de-risking with national pragmatism. Chinese investment has shifted from major takeovers to smaller greenfield projects under stricter “golden power” rules and EU screening mechanisms. Meloni’s alignment with the tougher US stance on China has reinforced this cautious, de-risking approach. Yet structural constraints remain: many Italian SMEs are linked to German supply chains that ultimately serve China. These dependencies could create domestic political risks if Italy attempts a radical decoupling from China. Italy’s exit from the BRI was a necessary recalibration and geopolitical realignment, not a rupture, as Sino-Italian ties have been repositioned toward a more pragmatic and cautious partnership.

The challenge ahead for Italy is to turn its reactive, domestically driven adjustments into a coherent long-term strategy that reconciles its domestic economic interests with transatlantic alignment. Italy’s ability to successfully balance US and EU demands with domestic economic realities will test both the strategic clarity of its vision and its skill in managing China as a geopolitical rival.

About the author

Related content

Explore the programs

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

Image: ITALY-CHINA/