Navigating the complexity of European policymaking on China

This is the second chapter of the report “Is Europe waking up to the China challenge? How geopolitics are reshaping EU and transatlantic strategy.” Read the full report here.

In a well-known anecdote often attributed to Henry Kissinger, the national security advisor allegedly asked, “Who do I call if I want to call Europe?”1Vanessa Gera, “Kissinger Says Calling Europe Quote Not Likely His,” Associated Press, June 27, 2012, https://www.yahoo.com/news/kissinger-says-calling-europe-quote-not-likely-145223724.html. Whether or not Kissinger actually voiced it, the question still resonates today—and reflects the uncertainty faced by outside observers trying to understand EU policies on China, unsure who holds ultimate authority.

EU policymaking on China involves a multilayered process in which institutions and member states pursue overlapping and sometimes conflicting interests. At the EU level, the European Commission, the European Parliament, the European Council, and the European External Action Service (EEAS) play distinct roles in shaping policy. At the same time, member states develop their own national approaches, influencing EU-level decision-making. The result is a complex, often opaque interplay of actors, issues, and interests that collectively shape the EU’s approach to China.

How does the EU’s policymaking process impact its China policy?

Much of the confusion about the EU’s China policy stems from its multilayered and complex decision-making structure. Broadly, China policy operates on two levels: the EU-level and the member state level. Different functional areas are covered by different rules and actors. Trade, for instance, is an exclusive EU competence—led by the Commission—while technological development and energy are shared competences between the EU and member states. Foreign policy and security policy are unique cases because the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is determined collectively at the EU-level, with member states formulating policy together in the Council by unanimous vote. Non-EU level foreign and security policy, in contrast, is autonomously shaped by individual member states.

At the EU-level, policy on China is formally adopted by the member states in the Council, but historically much of the initiative has come from the European Commission and, to some extent, the European Parliament. The Commission and Parliament are supranational bodies, while the European Council is intergovernmental, giving member states a direct role in shaping policy. In the European Council—the body of EU member state leaders—they agree on general guidelines, while joint actions and common positions are adopted in the Council of the European Union, which is composed of national ministers from each EU country. EU-level China policy thus emerges from the interaction between member states and EU institutions.

The role of EU institutions

EU-level China policy is shaped by the Commission, the European Council, the Parliament, and the EEAS—each exercising distinct functions and degrees of influence. The Commission serves as the EU’s executive, proposing legislation to the Council and Parliament and implementing policies; the Council acts as a co-legislator and sets the CFSP; and the Parliament reviews legislation while exercising democratic oversight.

With regard to China policy, the Commission plays a dominant role by preparing policy proposals, initiating legislation, and implementing policies. Within the CFSP, the Commission formally holds limited competences but has gradually acquired de facto influence, reducing member state veto power.2Akasemi Newsome and Marianne Riddervold, “The Role of EU Institutions in the Design of EU Foreign and Security Policies,” in The Routledge Handbook of European Security Law and Policy (London: Routledge, 2019), 55. It works closely with the EEAS, whose head also serves as Commission vice president. The Commission maintains oversight in key external-policy areas, including aid, development, energy, and trade. In these areas, it influences China policy through its “communications”—high-level policy papers that set EU priorities. Since 2019, under the first Ursula von der Leyen Commission, the EU has shifted from framing Beijing as a partner, competitor, and a systemic rival to emphasizing China as a “systemic rival,” codifying the EU’s “de-risking” in the European Economic Security Strategy.3“EU-China—A Strategic Outlook,” European Commission, March 12, 2019, https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2019-03/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf; “Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council, and the Council on European Economic Security Strategy,” European Union, June 20, 2023, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=JOIN:2023:20:FIN. The Commission has also leveraged its trade and regulatory powers to advance China-related policy, including instruments such as the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI), the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR), and the International Procurement Instrument (IPI).4“New Tool to Enable EU to Withstand Economic Coercion Enters into Force,” European Commission, press release, December 26, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_6804; “Foreign Subsidies Regulation,” European Commission, July 12, 2023, https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/foreign-subsidies-regulation_en; “International Public Procurement Instrument,” European Commission, last visited September 5, 2025, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/content/international-public-procurement-instrument.

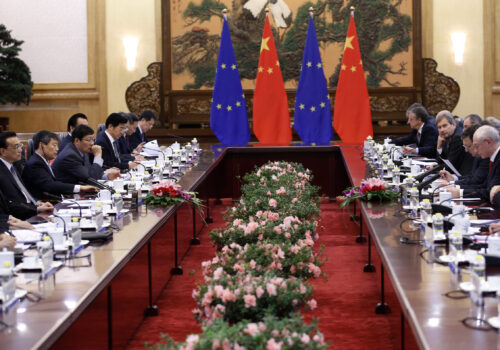

The Council adopts EU-level official policies on China within the CFSP framework. Comprising the heads of state and governments of each member state, it sets general guidelines, while the Council of Ministers—attended by relevant ministers—agrees on joint actions or common positions. The Council can establish diplomatic relations with China, as in 1975, and conclude agreements such as the 1978 Trade Agreement and the 1985 Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement.5“Trade Agreement between the European Economic Community and the People’ s Republic of China,” European Commission, May 2, 1978, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:21978A0403%2801%29; “Agreement on Trade and Economic Cooperation between the European Economic Community and the People’s Republic of China,” European Union, September 19, 1985, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/agree_internation/1985/2616/oj/eng. Council conclusions are typically declaratory, emphasizing EU values and principles, yet they carry weight due to collective member state authority. In practice, Council and Commission leaders coordinate external initiatives on China closely. They also meet Chinese leaders jointly at the annual EU-China Summit.

The European Parliament functions as a co-legislator and plays both advisory and agenda-setting roles. Members and committees actively debate China policy, publish reports, and issue resolutions. The 2009 Lisbon Treaty further strengthened the Parliament’s role, requiring its approval for major agreements with China—a power that the Parliament exercised when it suspended ratification of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) in 2021.6“EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (EU-China CAI),” European Parliament, June 20, 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-a-global-europe-leveraging-our-power-and-partnerships/file-eu-china-investment-agreement. It also publishes major policy documents, such as the 2021 EU-China strategy, reports on EU-China relations, and adopts resolutions addressing human rights and other issues.7Ibid.; “European Parliament Recommendation of 13 December 2023 to the Council and the Vice-President of the Commission/High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Concerning EU-China Relations,” European Parliament, 2023, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2023-0469_EN.html. The Parliament has maintained quasi-diplomatic relations with China over the past decade. At the same time, it has repeatedly employed tools such as the EU Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime, prompting China to sanction several of its members in 2021.8Unai Gómez-Hernández, “European Parliament Elections Will Set the Tone for EU-China Relations,” China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe, April 12, 2024, https://chinaobservers.eu/european-parliament-elections-will-set-the-tone-for-eu-china-relations.

Finally, the EEAS serves as the EU’s diplomatic service, coordinating central institutions and external bodies in implementing the CFSP. The High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR/VP), who appoints EEAS staff and oversees overall foreign policy, coordinates closely with the Commission and Council as Commission vice president and chair of the Council of Foreign Ministers. While the HR/VP represents EU China policy and ensures institutional coordination, the EEAS enacts it. However, both the HR/VP and the EEAS have limited influence over the policy’s formulation.

The role of the member states

The role of EU member states in shaping China policy is twofold. First, they participate in the Council, where they set the direction of EU-level policy. It should be noted, however, that the influence of member states varies significantly, and the Commission often plays an outsized role in steering policymaking. Second, each member state also formulates its own national policy on China.

As the Council formulates not only the CFSP but is also acts as a co-legislator on other policies and strategies related to China (e.g. economic security instruments), member states can shape policy decisions through the participation of their heads of state and government, as well as through the various configurations of the Council of the European Union, including the Foreign Affairs Council, the Economic and Financial Council, and the Competitiveness Council. Once member states formulate CFSP policies in the Council, they are obliged to implement them, and their national policies must align with EU positions.

At the same time, EU member states retain broad autonomy in developing their own bilateral policies toward China, despite the existence of the CFSP and the EU’s exclusive competence over trade. This autonomy allows states to declare strategic partnerships, sign agreements, or conclude memoranda of understanding with China on a wide range of issues, from education and culture to investment to security. A striking example is Hungary’s 2024 security cooperation agreement with China, which allows Chinese police officers to patrol on Hungarian territory.9Liz Lee and Ryan Woo, “In Unusual Move, China Offers to Back Hungary in Security Matters,” World, Reuters, February 20, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/unusual-move-china-offers-back-hungary-security-matters-2024-02-19.

Member states thus influence EU China policy both through their bilateral engagements with Beijing and through their decision-making on EU-level policy in the Council. Because member states’ preferences and priorities differ widely, reflecting divergent national interests, formulating a coherent and unified EU-level policy on China is highly complex. In practice, even after agreeing on common policies in the Council, some member states pursue actions that contradict EU-level decisions.

Differences among EU member states

Much of the ambiguity in EU policy on China arises from its multilayered and complex decision-making structure. EU institutions seek unity, but national governments often have divergent priorities, making coherence difficult. National approaches depend on the depth of bilateral relationships with China, the scale of economic and technological dependencies, tensions between business communities, leadership attitudes, and public opinion toward China. Together, these factors produce varied national policies that range from openness and engagement to strategic caution and restriction. The EU, meanwhile, tries to balance these positions by recognizing interdependence with China while managing strategic risks.

Intensity of European relationships with China

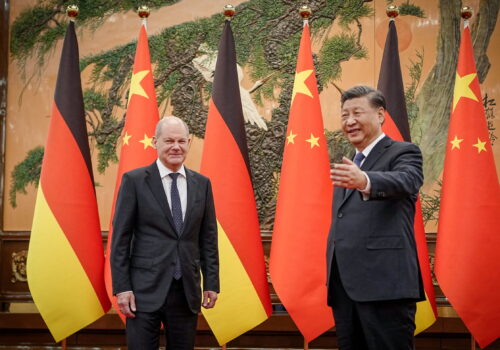

Broadly speaking, EU member states fall into three categories in terms of their relationships with China. The first group includes economic powerhouses such as Germany, France, Italy, and others, which have built long-term, multidimensional partnerships with China encompassing trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange. Many of these countries—for instance, Germany and France, have export-oriented economies and are especially sensitive to issues of market access in China. Their industrial competitiveness depends heavily on sectors such as automation, machinery, and chemicals, which are deeply integrated into Chinese supply chains and consumer markets.

Naturally, this group dominates European trade with China—with Germany alone accounting for roughly 35 percent—and has greater influence than others in shaping the EU’s overall China policy. Six member states—Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, France, Spain, and Poland—together represent around 75 percent of total EU-China trade.10Authors’ calculations based on Trading Economics data. Last visited August 24, 2025. Chinese investment in the EU is equally concentrated: since 2000, the United Kingdom ($92 billion), Germany ($38 billion), France ($26 billion), the Netherlands ($20 billion), and Italy ($16 billion) together have attracted 66 percent of cumulative Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the EU.11Statistics include the United Kingdom when it was still an EU member, but not since 2016. Agatha Kratz, et al., “Chinese Investment Rebounds Despite Growing Frictions: Chinese FDI in Europe: 2024 Update,” Mercator Institute for China Studies and Rhodium Group, May 21, 2025, https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-investment-rebounds-despite-growing-frictions-chinese-fdi-europe-2024-update.

This pattern reflects Beijing’s long-term objective of embedding itself in Europe’s advanced research and development networks. To advance its “Made in China 2025” strategy, Beijing has sought to acquire strategically important companies in Western Europe.12Valbona Zeneli, “China and Europe” in Scott D. McDonald and Michael C. Burgoyne, eds., “China’s Global Influence: Perspectives and Recommendations,” Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, 2019, https://dkiapcss.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/8-China_and_Europe-Zeneli.pdf. The concentration of Chinese FDI highlights how a select group of member states serves as the primary conduit for Europe’s engagement with China—and vice versa—shaping not only the EU’s opportunities but also its vulnerabilities.

Concerned about Chinese acquisitions—mainly state-owned enterprises—in February 2017, the economy ministers of Germany, France, and Italy jointly urged then-EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström to establish an EU-wide mechanism for screening foreign investments.13Gisela Grieger, “Foreign Direct Investment Screening: A Debate in Light of China-EU FDI Flows,” European Parliamentary Research Service, May 2017, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2017/603941/EPRS_BRI(2017)603941_EN.pdf. They warned that European expertise was at risk of being sold off without adequate safeguards to protect strategic technologies and infrastructure. Their appeal followed the takeover of the German robotics firm KUKA—one of Europe’s most advanced technological companies—by China’s Midea Group. France joined the appeal because it reflected its tradition of protecting strategic sectors, while Italy worried about Chinese incursions into its energy and transport industries following a surge of Chinese takeovers after the financial crisis. This push marked a turning point, as major EU economies pressed Brussels to balance open markets with security concerns, laying the groundwork for the EU’s 2019 investment-screening regulation and

today’s broader debate on economic security and sovereignty. However, even among these three countries, policies have been inconsistent, as their governments have oscillated between openness and caution. Italy abstained from voting on the screening mechanism in 2019 and, around the same time, signed onto China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Germany likewise failed to coordinate effectively to block Chinese investment in the port of Hamburg.

The second group comprises countries whose ties with China have deepened markedly in recent years, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. Hungary—and the candidate country Serbia—are the most prominent cases. Their relationships with Beijing have developed primarily under the “16+1” framework (later “17+1”, now “14+1”), launched by China in 2012 to strengthen its engagement with new EU member states and candidate countries in the Western Balkans. Several of these states have since upgraded their bilateral relationship with Beijing to strategic partnerships and joined the BRI. In the past two years, Hungary has emerged as the predominant destination for Chinese FDI in Europe, particularly in electric-vehicle and battery manufacturing. In 2024, Hungary alone absorbed nearly 31 percent of all Chinese FDI in the EU and the United Kingdom.14Kratz, et al., “Chinese Investment Rebounds Despite Growing Frictions: Chinese FDI in Europe.”

Beijing’s cooperation with certain countries in regional frameworks such as 16+1 has raised concerns in the EU that, by acquiring strategic assets, China has gained political influence, strengthened its bargaining position vis-à-vis Brussels, and expanded its capacity to “divide and rule” the continent—weakening the EU’s ability to speak with one voice. Evidence suggests that in countries where Chinese presence is more pronounced, foreign policy choices have tended to align with Beijing, often opposing common EU positions on issues ranging from human rights to the South China Sea. For example, in April 2018, Hungary stood out as the only EU member state to refuse endorsement of a report critical of Beijing’s BRI. Similarly, Greece—which joined the 16+1 framework in 2019—together with Hungary and Croatia, diverged from the European consensus in 2016 by blocking the EU from endorsing the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling in favor of the Philippines in its case against China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea.15Robin Emmott, “EU’s Statement on South China Sea Reflects Divisions,” Reuters, July 15, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southchinasea-ruling-eu-idUSKCN0ZV1TS. Moreover, Athens later vetoed an EU statement on China’s human rights record, dismissing it as “unconstructive criticism of China”.16Robin Emmott and Angeliki Koutantou, “Greece Blocks EU Statement on China Human Rights at UN,” Reuters, June 18, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/greece-blocks-eu-statement-on-china-human-rights-at-un-idUSKBN1990FP.

Countries in these first two groups are heavily reliant on raw materials and technology supply chains—from semiconductors to rare earth elements and green technologies. These dependencies create structural asymmetries, such as those related to Chinese solar panels and batteries, which directly affect Europe’s energy transition policies. In addition, some states remain vulnerable due to dependencies in critical infrastructure, notably their continued reliance on Chinese firms like Huawei for telecommunications networks.

The third group of countries includes EU member states with limited engagement—those with weaker economic and political links to China, such as the Nordic and Baltic states. With minimal trade and economic ties to Beijing, these countries tend to pursue values-based policies that emphasize human rights and security concerns, often aligning closely with US positions. Twelve EU member states in this group—including Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Croatia, Cyprus, and Slovenia—account for less than five percent of the EU’s total trade with China.

Business interests, public attitudes, and domestic politics

Domestic political dynamics, including the interplay between business interests, leadership styles, and public opinion, further shape EU member states’ approaches to China. The business community—particularly in EU countries with large trade and economic dependencies on China—often lobbies for stable and pragmatic relations with Beijing to safeguard market access and supply chains. This frequently conflicts with public policy actors, who increasingly emphasize security concerns (especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the “no-limits” partnership between China and Russia), human rights issues (for instance, in Hong Kong and in relation to the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang,) and resilience against strategic dependencies (especially after the COVID-19 pandemic). In some cases, governments have tightened screening mechanisms for Chinese investment even as companies sought to expand partnerships and joint ventures in China, creating friction between business elites and policymakers.

Similarly, national leadership styles and political cultures also strongly influence approaches. French leaders, for instance, often frame China policy in terms of strategic autonomy and global competition. German leaders, by contrast, traditionally emphasized “Wandel durch Handel”— change through trade—but have shifted toward de-risking in recent years. In countries where skepticism toward authoritarian regimes is high (for example, in the Baltic states and the Czech Republic), governments often adopt tougher stances, whereas public opinion in other countries remains more ambivalent, especially when economic benefits are at stake. Moreover, populist or nationalist administrations, such as Hungary’s Orbán government, sometimes instrumentalize relations with China as a counterweight to Brussels.

Just as European governments differ in their political approaches to Beijing, public attitudes toward China are far from uniform. These variations often mirror differences in economic exposure and security concerns, complicating efforts to forge a coherent EU China strategy. Recent polls suggest that many Europeans view China as a “necessary partner” (39 percent), rather than an ally (4 percent) or an adversary (26 percent). However, Southern Europeans generally hold more favorable views, reflecting perceived economic benefits, while Northern Europeans remain more skeptical, shaped by cautionary lessons on interdependence. Eastern Europeans, by contrast, express the strongest concern over Beijing’s deepening ties with Moscow.17Jana Puglierin, Arturo Varvelli, and Pawel Zerka, “Transatlantic Twilight: European Public Opinion and the Long Shadow of Trump,” European Council on Foreign Relations, February 12, 2025, https://ecfr.eu/publication/transatlantic-twilight-european-public-opinion-and-the-long-shadow-of-trump/#the-china-conundrum.

Conclusion

When it comes to the complexity of European political and policymaking processes on China, two conclusions stand out. First, EU policymaking on China is complex not only in appearance but also in practice. Since both EU institutions and member states are involved, contradictions naturally emerge. While national governments pursue their own interests, EU-level policies are designed to reflect the bloc’s broader geopolitical stance. Second, although member states pursue their own bilateral China policies, their influence still shapes EU-level approaches, which evolve through constant interaction between EU institutions and member state representatives.

The European Commission, at the heart of the EU’s institutional framework, has played a pivotal role in shaping EU China policy for decades, working closely with the European Council, the European Parliament, and the EEAS. The Parliament, strengthened by the Lisbon Treaty, has become increasingly influential—a development that is reflected by its rejection of the CAI and its continued push for a tougher line on human rights. Contrary to assumptions of constant disunity, the EU institutions have generally agreed on the overall direction of China policy. The more persistent divergence lies between EU-level consensus and the China policies of individual member states.

Divergent national interests, economic dependencies, and political orientations among EU member states add another layer of complexity to the EU’s collective approach on China. Major economies such as Germany, France, and Italy maintain deep economic engagement with China but also promote regulatory measures to protect strategic sectors. In contrast, many Central and Eastern European countries—most notably Hungary—favor closer political and economic ties with Beijing, raising concerns that China may exploit these internal divisions within the EU. Meanwhile, smaller states with limited links to Beijing, particularly in the Baltics and in Northern Europe, tend to support approaches centered on security and shared values. These differences are further intensified by domestic tensions between business communities, which seek stable market access, and policymakers, who often prioritize resilience, human rights, and security.

Taken together, these dynamics highlight that the EU’s approach to China is not monolithic but instead reflects a patchwork of national interests that Brussels must continually reconcile. This reality makes achieving coherence and unity a constant challenge in EU policymaking on China.

About the author

Related content

Explore the programs

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

Image: In Belgium, European Parliament Chamber, on November 20, 2024, lawmakers from across the EU convene in the plenary chamber of the European Parliament to debate and pass legislation that impacts millions of European citizens. (Photo by Siavosh Hosseini/NurPhoto)NO USE FRANCE