Recommendations for coordinating US-EU policy

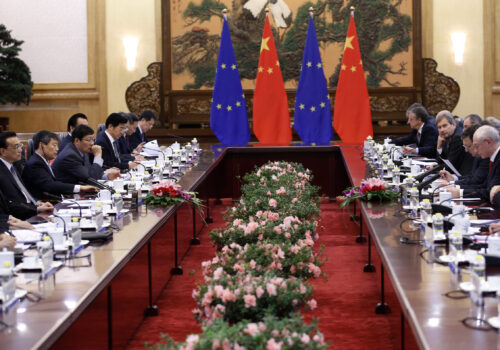

This is the final chapter of the report “Is Europe waking up to the China challenge? How geopolitics are reshaping EU and transatlantic strategy.” Read the full report here.

In recent years, European institutions have elevated China to a key priority on the European Union (EU) agenda, developing a comprehensive set of policies and strategic documents aimed at aligning member states more closely and strengthening transatlantic coordination. As the previous chapters of this report have shown, the EU’s China policy emerges from both formal and informal negotiations involving a wide range of actors. Where the EU holds exclusive competencies—such as in customs, competition, and trade—the European Commission and the European Parliament take the lead, producing the most consistent policy strands. The Commission’s Directorate-General for Trade (DG Trade) and the Parliament’s International Trade Committee (INTA) are particularly influential. By contrast, the EU’s role in foreign and security policy is far more limited, with decisions primarily left to member states via the European Council. The Council’s unanimity rule in this area has hindered a common position on China in the past, prompting several member states to advocate a shift toward qualified-majority voting to strengthen cohesion.

As this report has highlighted, the evolving transatlantic agenda on China is driven by four distinct forces: US-China rivalry, growing doubts about US engagement in Europe, the deepening Russia-China partnership, and China’s growing competitiveness in key sectors. Together, these pressures make closer US-EU coordination both urgent and necessary—not only in words but also in action. The United States should prioritize building durable mechanisms of cooperation with the EU in the areas that matter most: economic security, supply chains, anti-coercion, and strategic investment. Aligning US economic power with EU regulatory clout would enable the United States and the EU, as transatlantic partners, to shape global competition and respond to China with greater unity and credibility. The recommendations below are aimed at achieving this goal. They should be accompanied by the reestablishment of the Transatlantic Trade and Technology Council, a consultation forum initially founded under the first Trump administration, to coordinate China-related issues between the US administration and the European Commission.

Recommendations for US policy and strategy

Trade and investment

1. Deepen joint supply-chain de-risking of critical minerals

The United States should partner with the EU to launch a coordination platform on critical minerals and supply chains—backed by co-financing, harmonized standards, and strategic stockpiles—to put the shared doctrine of de-risking into practice. This would involve:

- Establishing a standing US–EU critical minerals coordination platform to jointly manage supply chains, reduce dependence on single suppliers, strengthen resilience, and align industrial policies. This platform could coordinate project pipelines, risk screening, and offtake calendars for lithium, cobalt, rare earths, and magnets, and would be led jointly by the European Commission’s DG Trade, the Enterprise Directorate-General (DG GROW), and US State Department officials, who oversee the US Minerals Security Partnership. It would reinforce transatlantic strategic alignment by creating a shared database, harmonizing risk assessments, synchronizing purchase schedules to prevent subsidy races, and conducting stress tests to establish buffer stock levels in critical sectors such as electric vehicles (EVs), renewable energy, and defense.

- Setting up a co-financing mechanism between the US International Development Finance Corporation and the European Investment Bank to support projects that de-risk third-country mining, processing, and recycling, and to attract private capital, modeled on the US-Australia-Japan infrastructure partnership.

- Harmonizing standards and supporting rare earth separation plants in Estonia and Sweden to expand EU processing capacity and secure US-EU offtake for defense and EV industries. Meanwhile, nickel- and cobalt-recycling hubs in Finland and Germany should be developed to reduce reliance on raw extraction and advance EU circular-economy goals—anchoring industrial cooperation in Germany and France.

2. Advance transatlantic convergence on investment screening

Inbound and outbound investment screening remain areas where US-EU cooperation has been attempted with limited success. While the EU has made progress, it has lagged behind US policy. One challenge is that, although the European Commission actively promotes strengthening investment screening, the authority ultimately rests with member states—and consensus among them is often lacking. Most recently, transatlantic parties discussed cooperation at the US-EU Trade and Technology Council meeting in April 2024.1“U.S-EU Joint Statement of the Trade and Technology Council,” White House, April 5, 2024, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/04/05/u-s-eu-joint-statement-of-the-trade-and-technology-council-3/. Despite these challenges, signs of potential transatlantic alignment are emerging. These include growing EU recognition of the risks Chinese investments pose to critical sectors2“European Parliament Endorses New Screening Rules for Foreign Investment in EU,” European Parliament, press release, May 8, 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20250502IPR28218/european-parliament-endorses-new-screening-rules-for-foreign-investment-in-eu. and the almost simultaneous rollout of new US and EU outbound investment screening regulations in January 2025.3Bob Savic, “U.S. and EU Strengthen FDI Screening Rules,” Geopolitical Intelligence Services, March 26, 2025, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/fdi-screening/. Based on these developments, we recommend that the United States re-engage Brussels to establish common threat perceptions and to cautiously explore member states’ willingness to coordinate on fortifying Europe’s defenses against Chinese security risks.

The United States should work with the EU and member states to coordinate both inbound foreign direct investment (FDI) and outbound investment controls, safeguard critical technologies and sensitive data, reduce asymmetries between US and EU policies, and develop a coherent, dual-track US-EU screening regime to keep strategic technologies and infrastructure under trusted control. Key steps include:

- Establishing a transatlantic investment screening forum to bring together the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), the European Commission’s DG Trade and Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services, and Capital Markets Union (DG FISMA), and national authorities to coordinate inward FDI. This forum could help expand intelligence sharing and integrate Financial Intelligence Units to track capital flows and investment structures linked to China.

- Institutionalizing joint risk monitoring by producing annual US-EU risk assessments of Chinese investment patterns in strategic sectors—drawing on US intelligence, the European Commission, and national regulators—and sharing findings with industry to guide compliance and risk-management practices.

- Advancing outbound FDI controls within the EU. The United States should work with the European Commission to develop future outbound investment restrictions aligned with shared definitions of sensitive technologies. This includes partnering with France and Italy as early adopters, engaging Germany to shape consensus, collaborating with the Netherlands on high-tech export-control expertise, and supporting Nordic, Central, and Eastern European states with best practices and capacity-building.

- Enhancing legislative engagement through a US Congress-European Parliament working group, supported by national parliamentary dialogues, staff exchanges, and technical briefings, to ensure transparent and durable political consensus on investment screening.

- Developing a transatlantic FDI monitoring instrument by proposing a US-EU mechanism that involves the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), CFIUS, Eurostat, and the European Central Bank, to track Chinese FDI systematically. This instrument would harmonize data methodologies, increase transparency, and provide timely intelligence on sectoral capital flows, thereby strengthening screening decisions and reducing regulatory arbitrage.

3. Discuss overcapacity and coordination of trade defenses

Both the United States and the EU face strikingly similar challenges from China’s industrial overcapacity and dumping, yet their approaches to trade are so divergent that no coordination under the current US administration has been possible. The EU approaches trade on the basis of the principles of free trade enshrined in the World Trade Organization, while US trade policy is based on an “America First” approach aimed at addressing decades of persistent “lack of reciprocity in our bilateral trade relationships.”4“Fact Sheet: The United States and European Union Reach Massive Trade Deal,” White House, July 28, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/07/fact-sheet-the-united-states-and-european-union-reach-massive-trade-deal/. Despite this gap, the challenges faced by both sides are nearly identical—and China exploits the loopholes created by incoherent US-EU policymaking to its advantage.

The United States and the EU should therefore re-engage to align their approaches to countering Chinese industrial overcapacity in critical sectors such as EVs, solar, and steel, where US broad tariffs and EU targeted duties currently diverge. This effort should include:

- Establishing a transatlantic trade defense forum as a standing platform for US and EU officials to discuss trade defense tools, share evidence of Chinese state subsidies, and seek to synchronize remedies.

- Aligning G7 messaging on Chinese overcapacity by leveraging the organization to issue unified warnings on destabilizing effects of Chinese overcapacity in EVs, solar, and steel. This could amplify deterrence, reassure industry of fair competition, and limit Beijing’s ability to exploit US-EU divisions.

- Coordinating enforcement of forced-labor import bans under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act with the EU’s forthcoming Forced-Labour Regulation to strengthen restrictions on goods linked to forced labor and enhance credibility.

Technology

1. Deepen US-EU coordination on semiconductors and the chip supply chain

Mirroring the 2025 US-EU trade framework, the United States should make semiconductors a top-tier track for transatlantic coordination—covering both advanced and “legacy” chips, fab tools and services, and subsidy rules—so that policy efforts reinforce each other and limit Chinese exploitation. Key measures should include:

- Aligning licensing standards for advanced chipmaking tools and related services—including installation, maintenance, software updates, and spare parts—with the Netherlands5The Netherlands is a crucial player in the global semiconductor industry, primarily due to ASML (Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography), the sole global supplier of EUV lithography machines needed for the most advanced chips. and the European Commission’s DG TRADE and Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content, and Technology (DG CONNECT). This would ensure mutually reinforcing controls consistent with the US-EU trade framework, in which the EU vowed to “work with the United States to adopt… [US] security requirements in a concerted effort to avoid technology leakage” to China.6“Joint Statement on a United States-European Union Framework on an Agreement on Reciprocal, Fair, and Balanced Trade,” White House, August 21, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/08/joint-statement-on-a-united-states-european-union-framework-on-an-agreement-on-reciprocal-fair-and-balanced-trade/.

- Piloting light outbound investment coordination with the Commission’s economic-security team using reciprocal notifications and shared risk categories for chips, supporting early alignment while the EU considers establishing a formal regime.

2. Align US-EU policy on AI, quantum, and defense-related technologies

China is making rapid progress in advanced technologies, with implications for both military and commercial sectors. It is therefore in the interest of the United States and the EU to coordinate policies on artificial intelligence (AI), quantum, and defense-relevant technologies. However, several obstacles remain. First, the EU—pursuing “strategic autonomy”—is concerned about dependence on US tech companies as well as Chinese firms. Second, the United States currently leads in AI and quantum computing, while the EU has lagged behind. Third, the EU has established a comprehensive data protection regime and a binding AI framework, whereas the United States has not. Nevertheless, both sides have complementary capabilities, and containing China unilaterally is not feasible. Expanding transatlantic discussions and coordination in this area is urgent.7“Tech 2030: A Roadmap for Europe-US Tech Cooperation,” Center for European Policy Analysis, September 30, 2025, https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/tech-2030-a-roadmap-for-europe-us-tech-cooperation/.

The United States should treat AI, quantum, and defense-relevant technologies as a top-tier US-EU coordination track—covering safety rules and testing, aligned listings and sanctions, tighter controls on risky transfers including services and data, light outbound-investment coordination, and joint action against Russia-related diversion. To align rules and reduce pathways for Chinese evasion, the United States should:

- Build an AI-governance bridge with the European Commission’s DG CONNECT to provide companies with a single set of expectations on high-risk uses, testing, transparency, and incident reporting, even if legal texts differ.

- Synchronize listings and sanctions affecting AI, quantum technology, and defense-linked firms with the Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS) to ensure common criteria and simultaneous timing for maximum impact.

- Collaborate with the Commission’s DG TRADE to bring export controls into alignment with the Trump administration’s AI Action Plan objective to “align protection measures globally,”8“AI Action Plan,” White House, July 2025, https://www.ai.gov/action-plan. and encourage the creation of an EU-wide export control framework.

- Pilot light outbound-investment coordination with the Commission’s economic-security team using reciprocal notifications and a simple shared-risk taxonomy for AI and quantum while the EU is considering a formal regime.

Security

1. Counter Chinese support for Russia’s war

While the EU has made notable progress in articulating its interests and tools regarding China in the economic domain, this strategic reflection has scarcely expanded to encompass global security and grand strategy. The March 2025 EU White Paper on Defense outlines in detail how China constitutes a “systemic challenge” for Europe, but navigating China’s grand strategy amid intensifying Sino-American competition and strengthening Sino-Russian partnership is complex, and the EU’s role as a security actor will hinge on the trajectory of these relationships. The United States should treat China’s support for Russia’s war in Ukraine as an urgent US-EU enforcement priority—covering synchronized listings, joint customs and financial targeting, shared industry advisories, coordinated border checks, outreach to key transit states, and rapid deconfliction. This approach would choke off procurement routes, close security gaps faster, and provide banks, shippers, and manufacturers with clear, consistent rules on both sides of the Atlantic. Key steps include:

- Prioritizing China-enabled procurement coordination with the European Commission’s DG TRADE and the EEAS, aligning listings and timing so actions land together, known intermediaries are shut down, and a clear message is sent to banks, shippers, and manufacturers.

- Building a small US-EU enforcement cell with the Commission and lead member states such as Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Lithuania to share real-time customs and financial red flags, match serial numbers and shipment data, and run coordinated end-use checks on high-risk consignments moving through hubs in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East.

- Issuing joint industry advisories with the Commission for freight forwarders, distributors, and university and lab partners, detailing China-related risks, simple screening steps, and reporting channels.

- Coordinating financial measures with the Commission and key finance ministries to block China-based intermediaries from accessing dollar and euro channels—pairing listings with practical guidance to banks on names, addresses, and tradecraft.

- Working with the Commission’s DG TRADE and customs authorities in priority member states—Poland, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia—to tighten border checks on items that originate from China and are rerouted to Russia through targeted inspection campaigns rather than blanket holds.

- Expanding joint outreach to key transit governments—in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Georgia, Türkiye, and the United Arab Emirates—offering training, scanners, and compliance toolkits while asking them to curb China-linked diversion networks.

- Briefing the European Parliament’s Committee on Foreign Affairs (AFET) and its Committee on International Trade (INTA) leadership to secure political and budget support for enforcement tools and reinforce the transatlantic position on China-linked evasion.

2. Counter China-linked espionage and cyber operations

The United States and the EU should treat counter-espionage and cyber defense as a shared priority, focused on Chinese state and proxy activity. This would ensure that investigations, public attributions, and protective measures move in step and close gaps that adversaries can exploit. The United States should:

- Coordinate counter-interference cases with the EEAS, the European Union Intelligence and Situation Center, and the European Commission, aligning investigative priorities on Chinese influence operations and overseas “police stations” and issuing joint guidance that universities, research councils, and local authorities can follow easily.

- Align public attribution and response with the EEAS and the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, agreeing on when to name Chinese actors, how to brief victims, and which immediate resilience steps operators should take across critical sectors.

- Synchronize listings and penalties for Chinese surveillance and defense firms with the Commission and the EEAS, timing actions jointly and pairing them with clear guidance to banks and platform operators.

- Run joint cyber-resilience sprints with the Commission and the EU Agency for Cybersecurity that focus on a few high-risk targets—government email, hospitals, ports, energy grid control systems—issuing straightforward hardening checklists and conducting follow-up scans to verify progress.

- Issue coordinated advisories with the Commission to technology vendors, cloud providers, and managed-service firms on China-linked cyber intrusions or espionage activity, including easy-to-understand red flags and a single reporting path usable on both sides of the Atlantic.

- The United States Congress and the European Parliament should establish a Transatlantic Legislative Forum on Countering Authoritarian Interference, with an initial focus on Chinese state and proxy activities. This forum would bring together members of the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China and the European Parliament’s Committee Foreign Interference to strengthen coordination and ensure coherent transatlantic approaches to counter-espionage, cyber defense, technology security, and strategic communication through joint hearings, secure briefings, and structured staff-level exchanges.

3. Coordinate with Europe on an Indo-Pacific approach to China

The United States and the EU should pursue a coordinated Indo-Pacific strategy toward China that links freedom-of-navigation messaging, presence at sea, Taiwan Strait diplomacy, partnerships with regional allies (Japan, South Korea, Australia, the Philippines, and India), defense-industrial cooperation with willing EU members, and sanctions and export-risk messaging. To implement this strategy, key actions should include:

- Aligning messages and actions on freedom of navigation and coercion at sea with the EEAS and key member states (France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands), pairing US operations and exercises with European port calls and patrols on a shared schedule and unified public messaging.

- Keeping Taiwan Strait diplomacy in lockstep with the EEAS by agreeing on standard phrasing regarding the status quo, coordinating high-level visits and parliamentary outreach, and establishing a quiet crisis-communications channel for rapid de-escalation messaging.

- Using NATO, the G7, and synchronized outreach to partners in the region (Japan, South Korea, Australia, the Philippines, and India) to roll out joint statements, tabletop exercises, and practical maritime capacity building, working with the EEAS Indo-Pacific team to avoid duplicate initiatives and share costs efficiently.

- Expanding practical defense-industrial ties with close US allies in the region while bringing in willing EU members where they add value (France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany), focusing on maintenance hubs, munitions availability, and interoperable communications rather than large new platforms requiring EU-wide consensus.

- Briefing the European Parliament’s AFET and its Subcommittee on Security and Defence (SEDE) leadership ahead of major Indo-Pacific announcements to secure political backing and maintain consistent public messaging on China, maritime rules, and crisis stability.

4. Strengthen coordination with Europe on China-related defense technology and critical infrastructure

The United States should work closely with the EU on China-related issues in defense technology and critical infrastructure. This includes coordinating on arms transfers, cooperation related to the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) security partnership with willing EU countries, protecting ports, energy and data hubs, addressing high-risk telecommunication vendors, and managing risks from military-civil-fusion. Doing so will strengthen resilience, close policy gaps, and give US and EU operators clear, predictable rules. To achieve this, the United States should take the following steps:

- Strengthen protection of critical infrastructure from China-linked risks by working with the Commission’s Directorate-General for Energy (DG ENER), DG CONNECT, and the EU Agency for Cybersecurity to develop simple, practical checklists of actionable security steps for ports, power grids, and data centers, giving operators one clear, consistent message.

- Coordinate with London and Canberra on AUKUS-related touchpoints and brief the Commission’s Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS) and EU member states—such as France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany—early on potential spillovers from AUKUS workstreams that will touch EU standards, supply chains, and workforce, allowing Europe to contribute wherever it adds value without formal membership.

- Explore the possibility of inviting EU NATO members to participate in future US Freedom of Navigation Operations, passing exercises, and the multilateral Rim of the Pacific Exercise alongside US allies in the Indo-Pacific region, while preserving their legal and operational integrity. The United States could establish a “Freedom of Navigation Partners Initiative” to facilitate parallel or sequential patrols by allies such as the United Kingdom, France, Australia, Japan, and Canada, ensuring a visible and sustained multinational presence in contested waters.

- Deepen cooperation on China-related military-civil fusion (MCF) risks with the Commission’s Directorate-General for Research and Innovation and DG DEFIS, giving universities, labs, and research funders a short, shared risk screen and a dedicated entity list of companies and institutions posing MCF or dual-use risk, ensuring that sensitive projects with clear defense implications are identified and stopped early.

- Establish a transatlantic mechanism (in cooperation with NATO) to identify and reduce Chinese investments in European strategic infrastructure that could undercut NATO’s ability to act both politically and militarily, especially in times of crisis. The starting point should be joint mapping of China-linked exposure in ports and logistics by working with the Commission’s Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport and coastal EU member states (the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, and Greece) to apply common risk tests for equipment, software, data access, and terminal stakes, and by coordinating review decisions and mitigation terms.

Conclusion

The research conducted for this report between November 2024 and October 2025 highlights several key findings regarding the EU’s evolving policies on China and their implications for US strategy and transatlantic unity.

The report finds that EU member states whose foreign policies are closely aligned with those of the United States tend to shape and support the European Commission’s approach to China, thereby influencing EU-level policy outcomes. This alignment strengthens transatlantic coordination but also exposes internal divisions within the EU, as not all member states share the same strategic outlook or level of risk tolerance toward Beijing.

Four geopolitical trends have collectively pushed the EU toward greater caution in its engagement with China: intensifying US-China strategic competition, uncertainty about continued US engagement globally and in Europe, Russia’s war on Ukraine backed by China, and China’s growing economic and competitiveness challenges to the EU. Together, these developments have prompted a shift toward balancing and de-risking strategies and a deeper recognition of the vulnerabilities and risks tied to economic dependence on Beijing.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the announcement of the China-Russia “no limits” partnership, most EU member states have adopted a more skeptical view not only of Moscow but also of Beijing, particularly given China’s support for Russia’s war effort. This shift has reinforced the European Commission’s position as a central actor in shaping EU-level policy on China and has prompted a gradual yet unmistakable movement toward a more unified strategic stance. Among the trends analyzed, this dynamic has had the most profound impact on the EU’s China policy.

Escalating US-China tensions represent the second most significant driver of change. As the rivalry between the two superpowers has intensified, the United States has increasingly encouraged its European partners to adopt complementary balancing measures. This has advanced transatlantic coordination, though differences remain regarding the extent—and the pace—of Europe’s alignment with US policy.

At the same time, the EU has become more attuned to China’s economic and competitiveness challenges. While the European Commission has taken the lead in crafting the EU’s economic security strategy, its success ultimately depends on implementation by member states. Progress has therefore been uneven, shaped by divergent national interests and persistent tensions between business communities seeking continued engagement with China and policymakers advocating stronger safeguards for economic resilience and security.

Overall, the EU is gradually moving toward a more strategic, cautious, and coherent approach to China. This evolution provides a renewed foundation for transatlantic cooperation—but only if the United States and Europe sustain close coordination to ensure that their respective China policies remain mutually reinforcing, forward-looking, and resilient in the face of a rapidly changing geopolitical environment.

About the authors

Related Content

Explore the programs

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

Image: European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen meets with U.S. President Donald Trump during the 80th United Nations General Assembly, in New York City, New York, U.S., September 23, 2025. REUTERS/Al Drago