The European Union (EU) is facing numerous crises, including massive migration flows, the UK’s vote to leave the EU (Brexit), and rising support for anti-EU and populist parties. In “The EU’s Capital Markets Union—Unlocking Investment Through Gradual Integration,” author Zdenek Kudrna, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Salzburg, argues that these crises all share one characteristic: They would be easier to resolve if EU economies grew faster. To reinvigorate economic growth across Europe, the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, launched the “Juncker Plan” in November 2014. Kudrna introduces the Capital Markets Union (CMU) as the core regulatory initiative of this plan.

The policy paper provides a brief overview of the CMU’s action plan and accompanying initiatives and the progress achieved during its first year. The author discusses multiple goals that motivated the European Commission to develop the CMU and assesses the likely impact of Brexit, which represents both a major blow and a major opportunity for completing the single capital market in the EU. Finally, the paper summarizes the lessons learned from similar EU initiatives over the last three decades to gauge the likelihood that the CMU will deliver on its promises.

This publication is part of the Atlantic Council’s EuroGrowth Initiative. The EuroGrowth Initiative is made possible by generous support from Beretta, the European Investment Bank, JPMorgan Chase & Co., United Parcel Service, Inc. (UPS), Ambassador C. Boyden Gray, and Ambassador Stuart Eizenstat.

This publication is in part funded by the European Union’s “Getting to Know Europe” program. The program aims to promote greater knowledge and understanding of the European Union and the significance of the EU-US transatlantic partnership within local and regional communities in the United States.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) is facing numerous crises, including wars in its neighborhood, terrorist attacks, massive migration flows, fragile economies on the southern periphery, unfinished reforms of the eurozone, the United Kingdom’s (UK’s) decision to leave the EU (Brexit), and rising support for anti-EU and populist parties. These unprecedented challenges all share one characteristic: they would be easier to resolve if EU economies grew faster.

The European Commission has launched numerous reform initiatives to stabilize European economies, increase their competitiveness, and stimulate growth. These reforms have focused primarily on the supply side of the economy, because fiscal policy remains firmly in the hands of national governments and the EU budget is limited to about 1 percent of its total gross domestic product (GDP). The Commission thus concentrates on regulatory reforms that remove barriers for cross-border investments.

The current Commission, headed by Jean-Claude Juncker, launched an Investment Plan on its inauguration in November 2014. The plan focuses on removing obstacles to investment, making smarter use of new and existing financial resources, and stimulating spending on infrastructure. The Capital Markets Union (CMU) is the core regulatory initiative of the plan, together with the Single Digital Market and the Single Energy Market. The CMU was developed by the UK’s commissioner, Jonathan Hill, in 2015 and, following his resignation after the UK’s Brexit referendum, is currently advanced by Commission Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis.1See European Commission, Green Paper: Building a Capital Markets Union (Brussels, 2015), http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=COM:2015:63:FIN&from=EN; European Commission, Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union (Brussels, 2015), http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0468&from=EN. All official documents are available on the European Commission’s CMU website at ec.europa.eu/finance/capital-markets-union. See European Commission, Green Paper: Building a Capital Markets Union (Brussels, 2015), http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=COM:2015:63:FIN&from=EN; European Commission, Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union (Brussels, 2015), http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0468&from=EN. All official documents are available on the European Commission’s CMU website at ec.europa.eu/finance/capital-markets-union.

This policy paper provides a brief overview of the CMU’s action plan and accompanying initiatives and the progress achieved during its first year. It discusses multiple goals that motivated the European Commission to develop the CMU and assesses the likely impact of Brexit, which represents both a major blow and a major opportunity for completing the single capital market in the EU. Finally, the paper summarizes the lessons learned from similar EU initiatives over the last three decades to gauge the likelihood that the CMU will deliver on its promises.

Key findings

- The EU needs to stimulate investment to improve economic growth and create new jobs.

- The EU capital markets remain underdeveloped; public equity markets are half the size of US markets despite the EU’s economy being slightly larger.

- The City of London, which serves as the EU’s financial center, is likely to leave the European Single Market in the next few years. This creates both the necessity and opportunity to develop competing financial centers elsewhere in continental Europe.

- Only cross-border capital markets can achieve the necessary scale because most EU member states’ economies are too small to develop complex and liquid markets.

- The eurozone needs an additional economic shock-absorption mechanism to address internal economic asymmetries.

- The Capital Markets Union is not a breakthrough achievement with immediate results, but an evolutionary development that needs to be sustained well beyond 2019 before it delivers tangible outcomes.

- The Commission should increase the CMU’s potential by complementing it with additional reforms such as supranational supervision, similar to the Banking Union, or the introduction of some kind of joint Eurobond.

Capital Markets Union: the proposal

The free movement of people, goods, services, and capital are the four fundamental goals of European economic integration. While the EU can guarantee nearly seamless trading in goods and unrestrained traveling for its citizens, the flow of capital and financial services suffers from fragmentation of markets along national lines. The recent financial crisis deepened the problem and even reversed economic integration, making EU capital markets less integrated than they were in 2008. To counter this development, the European Commission developed an action plan for a Capital Markets Union focusing on improvements in six domains.2The summary description is based on Angelos Delivorias, The Capital Markets Union Package (Brussels: European Parliamentary Research Service, 2015), http://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/the-capital-markets-union-package—european-parliament–1-10-2015.pdf.

- Providing financing for innovation, start-ups, and non-listed companies by following best practices for the development of crowdfunding and amending the legislation on European Venture Capital Funds and Social Entrepreneurship Funds.3These funds support young and innovative companies; the latter scheme targets those that combine a social, ethical, or environmental mission with the entrepreneurial goals. For small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) seeking financing, the CMU proposes to ensure that banks give structured feedback when declining SMEs’ credit applications; provide information on alternative funding options; and enhance private placements by developing standardized processes based on the International Capital Market Association and the German Schuldscheine regime.4The Schuldschein is a traditional German debt instrument with a typical maturity of two to ten years. It combines the legal features of a loan and bond, which make them attractive instruments for small volume transactions (typically €10 to 500 million). They are used by German SMEs as well as by banks and public authorities.

- Making it easier for companies to enter and raise capital on public markets by streamlining the information required and the approval process for securities prospectuses. In addition, the Commission plans to review regulatory barriers for publicly traded SMEs and develop a regulatory environment that fits the needs of SME-focused markets. The action plan also includes a review of how EU corporate bond markets are functioning, focusing on measures to improve market liquidity and assess the cumulative impact of regulatory reforms.

- Investing in infrastructure and sustainable development by recalibrating the regulatory framework for insurance companies; supporting long-term infrastructure financing through the European Fund for Strategic Investments; and developing standardized, transparent, and accountable environmental, social, and corporate governance for investments, including green bonds.

- Fostering retail and institutional investment by reassessing European markets for retail investment products and assessing the case for a policy framework to establish a successful European market for simple and competitive personal pensions. The Commission also plans to evaluate potential changes in the context of the Solvency II review, eliminating key barriers to the cross-border distribution of investment funds.5Solvency II is an EU legislative program that introduced a new, harmonized EU-wide insurance regulatory regime in 2016. Its structure was inspired by the Basel II approach to bank regulation.

- Leveraging banking capacity to support the wider economy by proposing an EU framework for simple, transparent, and standardized (STS) securitization combined with new prudential calibrations of banks’ capital requirements; starting a consultation on the development of a pan-European framework for covered bonds that combines well-functioning national regimes and market best practices; and exploring the possibility of exempting credit unions and nonprofit cooperatives serving SMEs from EU’s capital requirements framework for banks.

- Facilitating cross-border investing by removing the barriers to cross-border clearing and settlement identified by the Giovannini Group.6The Giovannini Group of experts identified fifteen barriers rooted in different market practices, regulatory requirements, tax procedures, and guarantees of legal certainty in 2001, and proposed a strategy to gradually remove these impediments in 2003. The Commission also proposes to introduce principles-based legislation on business insolvency and early restructuring as well as a code of conduct on withholding-tax-relief principles and standardized refund procedures, which would reduce national barriers for cross-border capital market development.

The above goals are to be achieved within five years (see timeline below) through collaboration among regulatory and supervisory agencies on the EU and national levels. While the Commission plans to complete the CMU by 2019, the European Parliament has urged a 2018 deadline. The process is monitored by annual progress reports and a midterm review in 2017. The first report was published in September 2016. It concluded that the action plan is broadly on track, but cautioned that the CMU’s effects will need time to materialize. The new legislation on STS securitization has made the most progress, but is only halfway through the EU legislative process. Similarly, harmonized rules for security prospectuses and the proposal on venture capital markets and social investments are not expected before the end of 2016.

Timeline for the Capital Markets Union initiative

The timeline for implementation of the CMU covers the full term of the Juncker Commission (2014 to 2019).* The early measures focus on encouraging access to finance, while the later period focuses on eliminating barriers stemming from national differences in taxation, securities regulation, and insolvency laws.

2014

- Juncker’s European Commission unveiled a plan to boost growth and jobs

2015

- Over seven hundred stakeholders contributed to the consultation on the CMU green paper

- Action Plan on CMU was launched by the Commission

- Drafts of the securitization and prospectus rules were published

- Consultations were launched on the following: covered bonds, insurance recalibration (Solvency II), infrastructural investment funds (so-called European long-term investment funds), retail finance, and the cumulative impact of financial reforms

- European Parliament urged implementation of the CMU by 2018 rather than 2019

2016

- June status report confirms all initiatives are broadly on track

- Legislative initiatives on the following are launched: venture capital, social entrepreneurship, loan origination by funds, and cross-border funds’ investments

- Reports on personal pensions and crowdfunding are due

2017

- Midterm review

- Reports on the following are due: exploring initiatives on SMEs’ access to funding, retail investments, bond markets, tax base, venture capital tax incentives, and information systems and government support

2018

- The following will be started: legislative initiatives on cross-border tax changes, insolvency regime harmonization, and additional Solvency II recalibration

- Report on retail investment markets is due

- European Parliament’s deadline for CMU implementation

2019

- European Commission’s deadline for CMU implementation

- CMU will be handed over to the next European Commission

* The Juncker Commission strives to act in a more political manner than most of its predecessors. It has issued a manifesto of ten priorities for jobs, growth, fairness, and democratic change. It is available at ec.europa.eu/priorities.

The drivers of the Capital Markets Union

Several policy rationales converge in the CMU’s action plan. While the headline motivation is “growth and jobs,” its design is driven primarily by the need to streamline EU and national legislation to remove barriers that protect the dominant role of banks and deprive the eurozone of a private-sector shock-absorption mechanism. As it stands now, the initiative has the potential to improve the integration and diversification of capital markets, but it lacks any game-changing measure that could speed up the glacial pace of capital market integration in Europe.

Growth and jobs

Growth and jobs are the CMU’s ultimate objectives, yet the initiative does not contain any policy instrument that directly impacts GDP or employment. Arguably, the growth of the EU economies is constrained primarily on the demand side as most countries pursue restricted fiscal policies. In the prosperous northern countries, such as Germany, that can afford to increase public investments and reduce taxes to expand aggregate demand, majorities of their voters support deficit and debt reductions. In contrast, macroeconomic expansion in the southern EU countries, such as Italy or Greece, and eastern states, such as Poland or Hungary, is constrained by various combinations of past debts, weak banking sectors, and general economic uncertainty. As a result, macroeconomic policies across the EU remain biased toward austerity and do not adequately complement the expansionary monetary policy of the European Central Bank (ECB) and other central banks in Europe.

Growth and jobs are the CMU’s ultimate objectives. . .

The European Commission cannot step in and provide fiscal stimulus on its own as its overall budget is limited to about 1 percent of the EU28 economy. Its policy toolbox is thus reduced to regulatory initiatives, such as CMU, that can stimulate the economy only indirectly. At the same time, there are policy proposals, such as the joint issuance of bonds, that could create a major breakthrough for development of the EU-wide capital market and foster higher growth and more jobs by alleviating fiscal constraints on stagnating economies.

Since the start of the euro crisis, academics and practitioners have put forward many proposals for a joint eurozone/EU issuance of bonds. The Commission explored several potential designs of joint bonds in a green paper on stability bonds in 2011.7European Commission, Green Paper on the Feasibility of Introducing Stability Bonds (Brussels, 2011), ec.europa.eu/europe2020/pdf/green_paper_en.pdf. In addition, the EU’s Five Presidents’ Report outlined a long-term vision for the eurozone that also included some aspects of a fiscal and political union by 2025.8Jean-Claude Juncker, Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union (Brussels: European Commission, 2015), ec.europa.eu/priorities/sites/beta-political/files/5-presidents-report_en.pdf. Although this vision remains vague, it spells out principles for the fiscal stabilization mechanism: the mechanism should not lead to permanent transfers; it should not undermine incentives for sound fiscal policy; and it should improve the through-the-cycle resilience of the eurozone. Various designs of joint Eurobonds could meet these criteria and provide the capital markets with a liquid, risk-free asset that could improve the transmission mechanism of monetary policy, support the diversification of the balance sheets of European banks, and induce the creation of cross-border banking groups.9See Ángel Ubide, “Stability Bonds for the Eurozone,” VOX, December 9, 2015, voxeu.org/article/stability-bonds-eurozone. In turn, these effects would enhance the shock-absorption capacity of the EU’s economies by diversifying risks on a cross-border basis and breaking the vicious sovereign bank link that led the eurozone to the brink of break up in 2012.10Eurozone member states agreed on the financing of the European Stability Mechanism (and its predecessor, the European Financial Stability Facility) though jointly guaranteed bonds. However, their use is limited to temporary stabilization programs in crisis countries.

Combining the CMU with joint bonds would represent a major breakthrough for capital market development and would directly impact jobs and growth across participating countries. Yet, the political debate on adopting Eurobonds is currently stalled as Germany and other northern eurozone members view any proposal as an attempt of southern countries to share the cost of fiscal misgovernance and avoid the need to complete structural reforms.11See Daniel Gros, “Eurobonds: Wrong Solution for Legal, Political, and Economic Reasons,” VOX, August 24, 2011, voxeu.org/article/eurobonds-are-wrong-solution. In the absence of a political consensus on Eurobonds, the CMU can improve growth and job prospects only indirectly and over the long term.

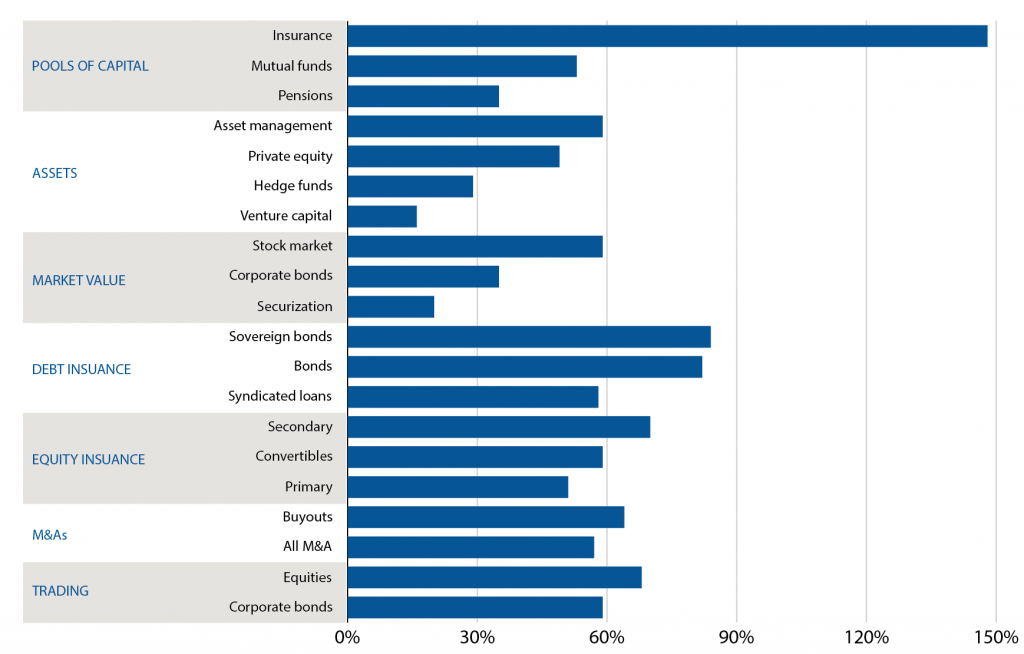

Figure 1. The size of and activity on European capital market segments as a proportion of corresponding US segments (both are expressed as a percentage of GDP)

Reducing dependency on banks

The EU financial system is dominated by large, universal banks. These banks provide about 80 percent of corporate debt, while the corporate bond markets supply the rest. In the United States, the situation is almost the opposite (see figure 1). Although the bank-based system has worked rather well for most EU economies historically, nearly all large banks were severely weakened during the financial crisis. Currently, their poor financial health provides a major drag on the financing of economic growth and poses a persistent risk to financial stability. Hence, the EU would benefit from rebalancing its economic structures toward more market-based finance.

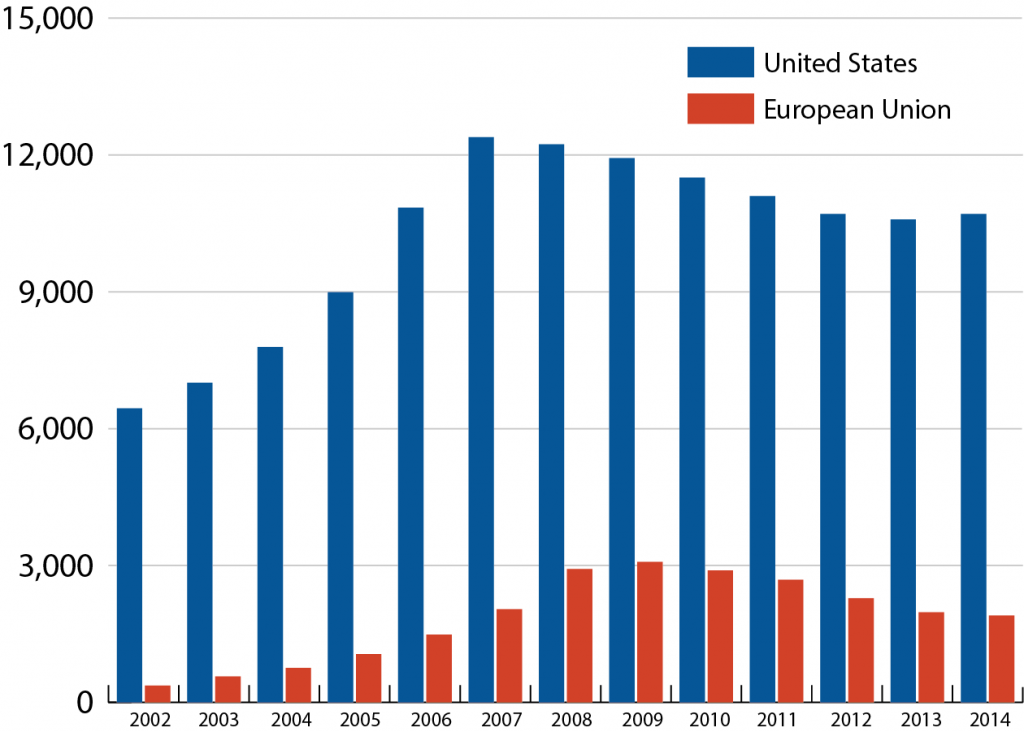

The CMU should help with the rebalancing process by integrating nationally fragmented capital markets. This would improve the efficiency and stability of the capital markets by enhancing opportunities for diversification. The CMU measure with the most significant and immediate potential impact is the commitment to introduce STS securitizations. Although the securitization market in the EU is much smaller than that in the United States (see figure 2)—primarily due to the absence of government-sponsored entities in residential mortgages—merely returning to the pre-crisis average would add €100 to €150 billion to the financing of the EU’s economy.12“A European Framework for Simple and Transparent Securitisation,” Fact Sheet, European Commission, 2015, europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-15-5733_en.pdf.

The EU also needs to stimulate the issuance of equities, which the CMU aims to achieve by streamlining rules for securities prospectuses and simplifying market entry. This is particularly important because SMEs contribute a higher proportion of GDP in the EU than they do in the United States, but their access to non-bank financing is much more limited in the EU. The EU can emulate some US measures introduced in support of start-ups and other small firms by reducing access barriers to public training platforms and by developing venture capital, private financing, and crowdfunding. However, since the stock exchanges and financing platforms for SMEs have appeared only recently and only in a few EU countries, it will take a long time before private actors use and scale these improvements to volumes comparable to the United States.

Integrated capital markets would also lower economic volatility through increased geographic diversification of equities and bonds. . .

While the overall EU savings rate is higher than that in the United States (20 and 17 percent of GDP, respectively), most of it is deposited in banks located in the home country of the given saver. Hence, the CMU also needs to attract more household and corporate-sector savings in vehicles that will invest in capital markets and encourage them to diversify across the entire EU. Since insurance assets are proportionally larger in the EU than in the United States (see figure 1) and insurance companies are now looking for opportunities in the low interest rate environment, the CMU aims to change regulatory and self-imposed constraints on insurance investments. This recalibration should steer more capital towards both long-term infrastructure investments and venture capital funds.

The overall logic of the CMU initiative is to facilitate capital market development by reducing the dependency of EU economies on banks. However, this approach does not fully correspond to the United States’ historical experience, where the capital market evolution was at least partially motivated by legal restrictions imposed on banking. The Glass-Steagall Act that separated commercial and investment banking, Regulation Q that capped interest rates on bank deposits, and the restriction on bank charters to a single US state all induced innovations that expanded the role of capital markets at the expense of banks. The EU is considering some form of Glass-Steagall-like restrictions for the largest, systemically important banks, as suggested by the Liikanen report in 2012.13Erkki Liikanen et al., High-level Expert Group on Reforming the Structure of the EU Banking Sector, (Brussels: European Commission, 2012), ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/high-level_expert_group/report_en.pdf. However, the proposal lingers in the decision-making process,14European Commission, Capital Markets Union: First Status Report, (Brussels, 2016), ec.europa.eu/finance/capital-markets-union/docs/cmu-first-status-report_en.pdf. while being gradually watered down. If the restrictions are adopted, then—in combination with other banking regulatory reforms—it may provide additional incentive for capital market innovation and development.

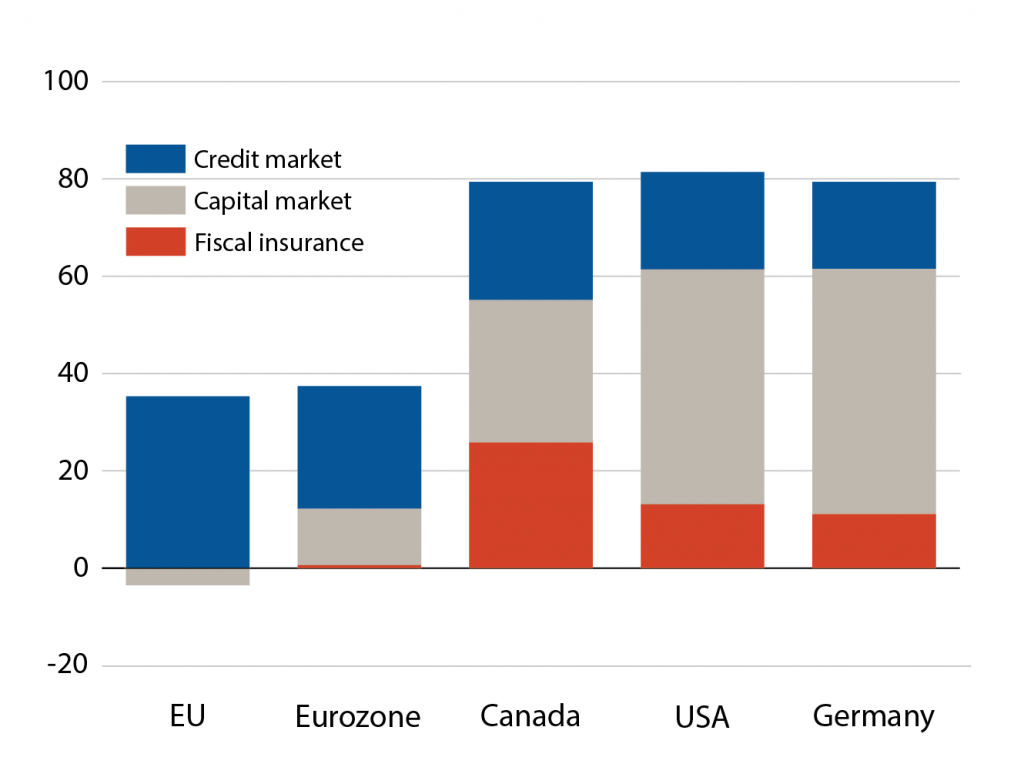

Macroeconomic shock-absorption

The macroeconomic shock-absorption capacity in the EU is lower than that in the United States because it lacks any form of federal redistribution and integrated capital market (see figure 3). This is a serious problem, especially for the eurozone countries that are unable to rely on country-specific monetary policy to respond to asymmetric shocks or financial crises.15Philip R. Lane, “The European Sovereign Debt Crisis,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 26, No. 3 (2012), 49–67. The expansion of integrated capital markets could provide additional capacity by increasing private-sector risk sharing. Integrated capital markets would also lower economic volatility through increased geographic diversification of equities and bonds, which makes these assets as well as general consumption and investments less sensitive to shocks in any one national economy. Moreover, cross-border capital flows should enable households and firms to lend to or borrow from other economies that are less impacted by any given crisis, while also involving a more diverse investor base with various funding profiles, trading horizons, and risk preferences, which also improves overall financial resilience.

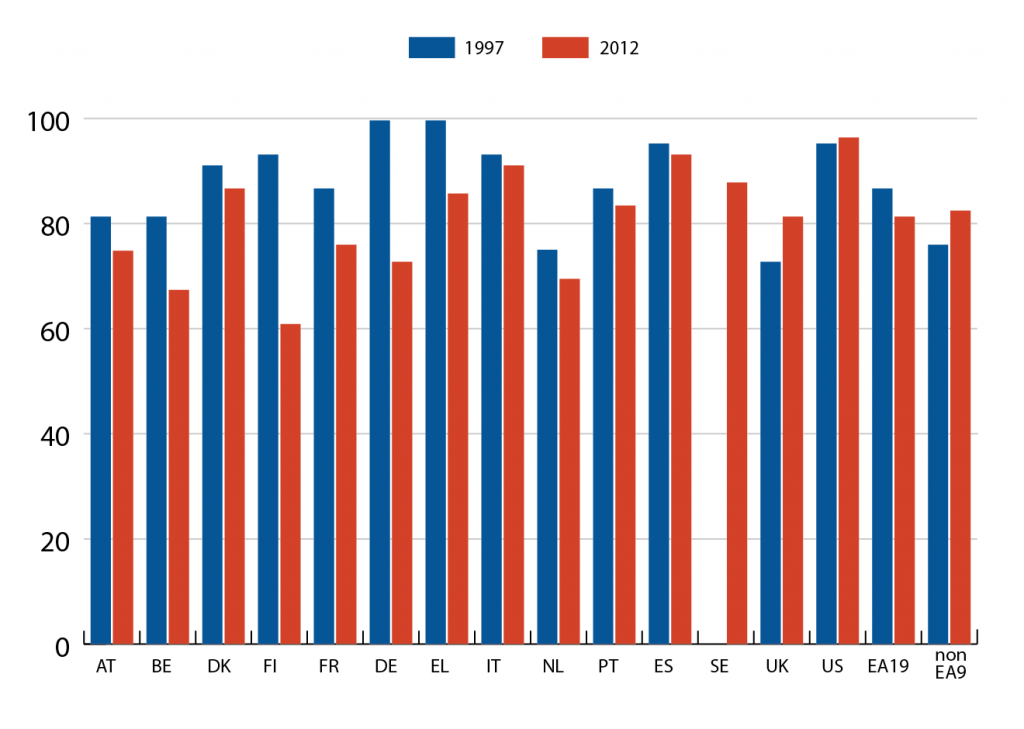

The EU capital markets are less integrated today than they were in 2008 because the financial crisis increased the tendency towards home bias (see figure 4). In uncertain periods, investors flee towards markets they are most familiar with, which has the negative consequences of concentrating risks in their portfolios, reducing portfolio diversification, and—when investors are banks—creating a dangerous link between the solvency of sovereigns and their banking sectors. The CMU can reduce home bias by lowering the costs of cross-border transactions and facilitating information flows (see figure 4). However, these steps require reducing impediments that stem from national differences in supervisory, regulatory, tax, and legal practices as well as, ultimately, cultural and language barriers.

Figure 2. US and EU securitization (USD billions)

Figure 3. Risk-sharing through fiscal, capital market, and credit channels (percent of shock smoothed by each channel)

Finishing the single market

The European Single Market will celebrate its twenty-fifth anniversary next year. While it has achieved major success integrating markets in goods, its results for financial services are less triumphant.16Elliot Posner and Nicolas Véron, “The EU and Financial Regulation: Power without Purpose?” Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 17, No. 3 (2010), 400–415. The Commission strove to keep the legislative framework updated and in line with market developments so most laws are in their third or fourth generation. It has also repeatedly attempted to launch initiatives to integrate EU capital markets on a cross-border basis. In 1996, it established the Giovannini Group of financial market experts to identify inefficiencies in EU financial markets and propose practical solutions to improve integration. In 1999, the Commission launched the Financial Services Action Plan to create a single capital market for the single currency. In 2001, the Lamfalussy expert group redesigned the regulatory governance of EU financial markets, which was consolidated by the introduction of European Supervisory Authorities in 2009. The CMU is thus an incremental next step in this series of similar schemes that strove to integrate and modernize the EU’s capital markets.17Emiliano Grossman and Patrick Leblond, “Financial Regulation in Europe: From the Battle of the Systems to a Jacobinist EU” in Jeremy Richardson (ed.), Constructing a Policy-Making State? Policy Dynamics in the EU (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 1–20.

All past initiatives were based on an idea that worked wonders for a single market in goods: that it is sufficient to eliminate barriers for cross-border trade and harmonize product standards for the markets to integrate seamlessly. However, this proved insufficient for regulated markets in financial services, where the enforcement of common standards inevitably provides considerable discretion to regulatory and supervisory authorities. As long as enforcement remains decentralized within a network of national supervisors, market fragmentation arises from differences in how each authority exercises its discretionary powers.18Zdenek Kudrna, “Financial Market Regulation: A ‘Lamfalussy Exit’ from the Joint-Decision Trap,” in Gerda Falkner (ed.), The EU’s Decision Traps: Comparing Policies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). National authorities within the EU do not necessarily trust each other; they defend their own turf and often protect national champions.19Nicolas Véron, “Europe’s Capital Markets Union and the New Single Market Challenge,” Bruegel, September 30, 2015, bruegel.org/2015/09/europes-capital-markets-union-and-the-new-single-market-challenge. Hence, without centralizing the enforcement powers on the EU level (i.e., supranationalization) the European Single Market in financial services will remain fragmented and its integration will proceed at a glacial pace as national enforcement practices gradually converge.

Figure 4. Degree of home bias in bond markets

Source: Anderson et al., A European Capital Markets Union.

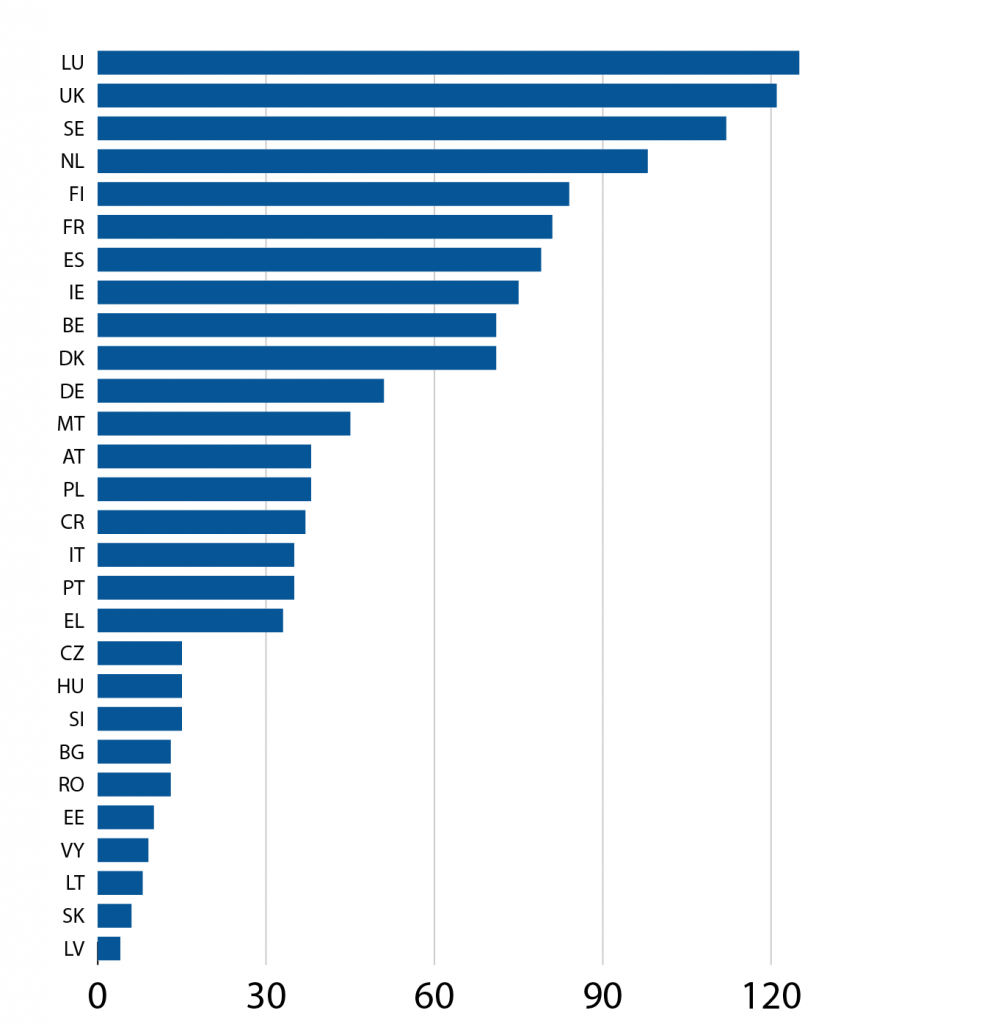

Figure 5. Stock market capitalization (percent of GDP)

The integration of the single capital market is particularly important for smaller member states that lack the scale necessary to develop complex and liquid markets (see figure 5). Consequently, companies from these countries are constrained by local financial circumstances, even if they do business successfully across the EU and globally. At the same time, differences in market size also indicate that there are variations in underlying economic structures and legal systems across EU member states. This also implies that following the CMU agenda will be more challenging for some countries that are likely to prefer a gradual pace of reforms.

None of the pre-CMU initiatives was able to shift enforcement powers to the supranational level because some member states—the UK most prominently among them—consistently opposed it. Each of the capital market initiatives over the last quarter century was thus limited to adopting common rules without common enforcement. Consequently, these initiatives removed some barriers for capital market integration by modernizing regulations, clarifying ambiguities, and eliminating unintended consequences of existing rules. Each of the barriers removed represented a step towards fully integrated capital markets, but none of them delivered any breakthrough that would have created a truly EU-wide capital market with supranational supervision. Unlike the similarly named Banking Union Initiative, the current version of the CMU lacks any supranationalization and therefore fails to address the fundamental problem, again.

Capital Markets Union after Brexit: less liberal, more supranational?

The UK is home to 27 percent of the EU’s listed companies by market value and 40 percent of its listed SMEs; moreover, 46 percent of the EU’s equity capital is raised through UK markets. The City of London is the undisputed financial center of Europe, which allows companies and investors to circumvent underdeveloped capital markets in their home countries. The Brexit referendum is likely to end this mutually beneficial arrangement as Theresa May’s conservative government seems to be leaning towards a “hard exit” that sacrifices single-market participation for control over immigration.20There is a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the post-Brexit status of the City as negotiation objectives and strategies of all key actors are only starting to emerge. It is still possible that the UK will be able to maintain some form of access to the single market. Hence, the UK—which was set to benefit most from CMU due to established competitive advantages—would now be threatened by it as the CMU is going to encourage a shift of business to the continent.

A UK departure would be a massive blow to capital market integration in Europe, but it would also be a major opportunity to increase the ambition of the CMU project.

A UK departure would be a massive blow to capital market integration in Europe, but it would also be a major opportunity to increase the ambition of the CMU project. The UK has been historically wary of supranational regulation. It has not joined the eurozone, avoided Banking Union, and consistently opposed delegation of supranational powers to EU agencies such as the European Supervisory Authorities. When formulating the CMU action plan, the Commission was aware that the UK government would be compelled to block any supranationalization during the run up to the June 2016 Brexit referendum. Consequently, the Commission avoided such proposals despite the recommendation of the Five Presidents’ Report that the Capital Markets Union “should lead ultimately to a single European capital markets supervisor.”21Juncker, Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union, 12. This means that the CMU legislation is to be enforced by a network of about thirty national and EU authorities, and will therefore inevitably be plagued by traditional problems of duplications, inconsistencies, turf wars, and tendencies to protect national champions. At the same time, the Banking Union adopted in June 2012 demonstrates that the eurozone is able to shift regulatory competences to the European Central Bank and related EU agencies. Brexit thus opens a new opportunity for the Commission to include the supranationalization of supervision to the CMU agenda. Transferring the clearing and settlement of euro-denominated securities from London to the eurozone and its supervision by some EU authority—long avoided at UK’s insistence—is likely to become only the first example of a more supranationalized CMU agenda.

The early political victim of Brexit was the British member of the European Commission, Jonathan Hill, who was responsible for the CMU and resigned after the referendum. His vision for the CMU was distinctly liberal, focused on removing barriers and avoiding regulatory interventions as much as possible. Without the UK’s voice at the table, the underlying approach to CMU is likely to become less liberal and include policy ideas emanating from continental Europe, such as the cultivation of financial-sector champions, the use of regulatory tools to support some indirect forms of industrial policy, or the introduction of excessively high standards of consumer protection. The UK departure may also help European banks water down CMU reforms that empower market-based competitors. Moreover, it is likely to strengthen voices that criticize the CMU agenda as a return to the pre-crisis trend of encouraging complexity and fragility in financial markets.22“Who Will Benefit from the Capital Markets Union?” Finance Watch, September 29, 2015, http://www.finance-watch.org/hot-topics/blog/1148-who-will-benefit-from-cmu.

The prospects of Capital Markets Union: lessons from past initiatives

Since the CMU proposal follows similar initiatives from the past, several observations can be made about the likelihood of its successful implementation. The CMU places emphasis on regulatory and legal framework changes, which need to undergo complex consultations—the adoption process of each package is thus likely to take at least two years. It will be a challenge to maintain political momentum throughout this process in the Council of the EU and European Parliament as other priorities and crises emerge. Moreover, the Commission cannot rely on the support of the ECB as in the case of the Banking Union, because the ECB does not have authority in capital market supervision.

Similar to every market initiative in the past, the CMU is exposed to a trade off between ambition and timely completion. The CMU combines some widely supported packages, such as simple securitization, with some notoriously difficult agendas, such as the harmonization of national insolvency laws. Hence, it is important for the Commission proposals that emerge from consultations to remain ambitious, while also avoiding lengthy political contestations (such as those that are currently blocking progress on related agendas including Liikanen’s bank restructuring or the adoption of a financial transaction tax). Moreover, since the CMU does not currently shift any supervisory powers to the EU level, the consistent day-to-day supervision of capital markets will depend on national authorities. Hence, pushing through an ambitious one-size-fits-all approach that does not accommodate legitimate country-specific circumstances is likely to face obstacles in the implementation phase. Therefore, it is better to focus on the less contested parts of the agenda, even if it means that the harmonization of capital market rules will have to continue beyond the self-imposed deadline in 2019.

At the same time, there are intervening factors that were not present when similar action plans were adopted in the past that can increase the chance of successful implementation. The UK departure represents a unique moment in EU history that makes success of the CMU much more urgent, as the other twenty-seven economies may no longer fall back on London to cover their capital market–related needs. The euro crisis has demonstrated the necessity of an additional shock-absorption mechanism for the eurozone, and deepening the private-sector risk sharing through CMU might be politically less difficult than agreeing on a corresponding fiscal mechanism. There also seems to be greater willingness to experiment with developing and harmonizing financial regulation, including the use of small-scale sandboxes to test innovations in financial technologies, increased reliance on international best practices, and collaboration with the industry outside of the UK. These circumstances conspire to increase the likelihood of successful completion, but also highlight the potential adverse consequences of an underachieving CMU.

Conclusion

The Capital Markets Union is an incremental initiative. Like similar projects in the past, it has the capacity to reduce barriers to capital market integration across the EU, but it delivers no major breakthrough. While it will fine-tune legislation and regulation of various market segments, it is not likely to induce a qualitative change in the structure of the European capital market. The distinguishing ambition of CMU is to make progress in converging the deep differences that underpin the fragmentation of the EU’s single capital market, such as the partial harmonization of the national insolvency law and variations in how capital is taxed. However, these issues are politically sensitive and—without drastic external pressure for reform—EU member governments are likely to prefer a gradual, step-by-step process that lasts years beyond the 2019 deadline.

The Commission may increase the CMU’s impact by instituting complementary reforms. It could centralize capital market supervision on the EU level, as Brexit creates both the political opportunity, by removing UK’s de facto veto on supranationalization, and economic necessity, by preventing other EU economies from relying on the City of London for their capital-market needs. The eurozone’s adoption of joint Eurobonds in some significant form could create the breakthrough moment for EU capital market development that reaches far beyond the current CMU ambitions. Similarly, imposing stringent regulatory and restructuring requirements on big banks could provide a stronger impetus for capital market development as was the case in the United States during the second half of the last century. However, without such enhancements, the Capital Markets Union is likely to remain a modest policy initiative with too grandiose a name.