The year 2019 marks one hundred and one years of relations between the United States and the countries of Central Europe that emerged from the wreckage of the First World War. After a century of work together, of tragedy and achievement, Central Europe and the United States have much to celebrate and defend, but also much to do. After accessions to NATO and the European Union, Central Europeans may have thought that their long road to the institutions of the West, and to the security and prosperity associated with them, was finished. The United States began to think so as well, concluding that its work and special role in Central Europe were complete.

Now, Central Europe, the United States, and the entire transatlantic community face new internal and external challenges. As a result, the transatlantic world has seen a rise of extremist politics and forms of nationalism that many thought had been banished forever after 1989. The great achievement of a Europe whole, free, and at peace, with Central Europe an integral part of it, is again in play. The Atlantic Council and GLOBSEC’s new report “The United States and Central Europe: Tasks for a Second Century Together” examines a century of relations between the United States and Central Europe: what went right, what went wrong, and what needs to be done about it.

Table of contents

What, then, must the United States and Central Europe do?

Introduction

The year 2019 marks one hundred and one years of relations between the United States and the countries of Central Europe that emerged from the wreckage of the First World War. They also celebrate thirty years since the end of the Cold War, as the peoples of Central Europe dismantled the Iron Curtain, sometimes literally.1This paper defines “Central Europe” as comprising the “Visegrad” countries (Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary), the Baltics (Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia), Romania, Bulgaria, and Slovenia and Croatia, the post-Yugoslav states now in NATO and the EU. Many of the arguments also apply as well to the Western Balkans, and to Europe’s east, especially Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova. But, these countries face challenges different from those already “inside” the institutions of the Euroatlantic community, and they deserve separate treatment and recommendations. Through their overthrow of communist regimes that year, and their success in democratic and free-market transformation, Central Europeans opened the door to a Europe whole, free, and at peace, allied with the United States—a powerful center of a strengthened democratic community also known as the “Free World.”

The United States supported this transformation because Americans had learned the hard way, through two World Wars and the Cold War, that their interests and future were tied to Europe, including Central Europe. This realization had been at the core of the US grand strategy ever since President Woodrow Wilson presented his Fourteen Points little more than a century ago.

With Central Europe’s subsequent accessions to NATO and the European Union (EU), Central Europeans may have thought that their long road to the institutions of the West, and to the security and prosperity associated with them, was finished. The United States began to think so as well, and concluded that its work and special role in Central Europe were complete.

This judgment may have been premature. Central Europe, the United States, and the entire transatlantic community face new external challenges from powerful authoritarians—from Russian aggression, both overt and covert, and from Chinese ambition. They also face challenges generated from within: economic stresses, concerns about national identity, and loss of confidence in their own institutions and even democratic principles. As a result, the transatlantic world has seen a rise of extremist politics and forms of nationalism that many thought had been banished forever after 1989. The great achievement of a Europe whole, free, and at peace, with Central Europe an integral part of it, is again in play.

After a century of work together, of tragedy and achievement, Central Europe and the United States have much to celebrate and defend, but also much to do.

This paper examines a century of relations between the United States and Central Europe: what went right, what went wrong, and what needs to be done about it.

The hard road to success

A narrative of tragedy and achievement emerges from the anniversaries marked in 2019, conveying the sweep of US-Central European relations, including

- one hundred and one years of US relations with the newly independent nations of Central Europe;

- eighty years from the catastrophic failure of European security and the start of the Second World War, in part the baleful result of US strategic withdrawal from Europe;

- thirty years since the overthrow of the Soviet-imposed communist regimes in Central Europe, which generated immediate and sustained US (and general Western) support and led to the end of “Yalta Europe”;2“Yalta Europe” refers to a Europe divided by Joseph Stalin with the acquiescence, however grudging, of Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, symbolized by agreements reached at the Yalta Conference of the United States, UK, and USSR in February 1945.

- twenty years since NATO’s first enlargement beyond the Iron Curtain, a process in which the United States played a leading role;

- fifteen years since the EU’s enlargement beyond that same line, a process led by Europeans and supported by the United States; and fifteen years since NATO’s “Big Bang” expansion, including Slovakia.

Central Europe’s history is indivisible from the great themes of European and world history, and the United States’ policy toward Central Europe cannot be separated from its general policy toward Europe or global strategy. In the past, when the United States attempted to make this separation—to treat Central Europe as apart from, and subordinate to, other foreign policy interests—it ended up with bad policy and worse results.

Launch of the first American grand strategy. The first US policy toward Central Europe was embedded in President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the United States’ first grand strategy, which Wilson presented to the US Congress in January 1918. He took these principles to Europe when he sailed there in early 1919, just after the end of World War I, trying to organize a rules-based world, a new system built on a foundation of US power and reflecting democratic values. The Fourteen Points—a major break with centuries of great-power practice—included

- “equality of trade conditions” instead of closed economic empires;

- limitations on (though not yet an end to) colonialism;

- inviting post-war Germany and post-revolutionary Russia into the new system if, but only if, they respected its rules;

- welcoming the emergence or re-emergence of nation states in Central and Eastern Europe; and

- establishment of a League of Nations, backed by US power, to enforce the peace.

This strategy was not vapid “Wilsonian idealism,” as it is often dismissed, but reflected shrewd assumptions (and massive self-confidence) that: “Yankee ingenuity” would flourish best in a rules-based, open world without closed economic empires; US national interests would advance with democracy and the rule of law; the United States would prosper best when other nations prospered as well; and, thus, the United States could make the world a better place and get rich in the process. Its flaws notwithstanding, this first US effort at world leadership ought to be seen in the context of the competition: Vladimir Lenin’s world communist revolution and French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau’s rebooted great-power system.

In this grand strategy, Central Europe’s new nations were to be an integral part of the new system, embedded in an undivided transatlantic community with their independence and security implicitly underwritten by American power. Little wonder that Central Europeans—living in vulnerable states between a sullen Germany and aggressive Bolshevik Russia—liked it (the Poles and Czechoslovaks especially). The legacy of this appreciation still lingers. On the centenary of the Fourteen Points in 2018, Warsaw’s main downtown street near the Presidential Palace had a large outdoor display in honor of Wilson and the Fourteen Points (which is more than can be said for Washington or New York.)

But, Wilson’s Fourteen Points did not survive their first contact with reality at the Versailles Peace Conference. As Clemenceau famously forecast, “God gave us the Ten Commandments and we broke them. Wilson gives us the Fourteen Points. We shall see.”France and the UK insisted on imposing a punitive settlement against Germany, rather than welcoming it back to the European family, and the new nations of Central Europe were more fractious than Wilson and his foreign policy team anticipated. They were insecure, often poor, administratively weak, sometimes unsatisfied with post-war borders (especially Hungary, but also Poland, which would shortly be attacked by Bolshevik Russia); and with large, often unsatisfied minorities. Creating more or less homogenous nation states in Central Europe was not possible, given where people actually lived.

The most profound US failure was its unwillingness to underwrite the flawed, but potentially workable, peace that emerged from the Treaty of Versailles. Communist Russia was still weak. The emerging nations of Central Europe were still democracies, seeking allies and models. Even after Versailles, the Germans still had pro-Western leaders. The weaknesses of the Treaty of Versailles might have been mitigated had the United States taken responsibility for implementing the peace of which it was co-author.

Instead, the United States withdrew from Europe. Wilson’s political rigidity at home killed the US Senate’s ratification of the League of Nations. Wilson was a broken man finishing his term in ill health, and the United States abandoned his attempt at world leadership. It left the Germans to themselves, and the French to deal with the Germans. It also forgot about the Poles, Czechoslovaks, and Yugoslavs, of whose independence the United States was a sponsor.

Yalta: axioms of a divided Europe. The catastrophic results are worth recalling. In the power vacuum of US withdrawal and under pressure of the Great Depression starting in 1929, the European post-World War I order collapsed, with Adolf Hitler’s Germany acting as a revisionist power in the face of weak resistance from France and Britain. In 1939, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin partitioned Central and Eastern Europe with Nazi Germany, and the Second World War was on.

US President Franklin Roosevelt’s initial war aims recalled the Fourteen Points. In August 1941, Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill issued the Atlantic Charter, which essentially sought to apply the Fourteen Points’ principles to a prospective post-World War II settlement, including all of Europe. But, the military reality of World War II, and the consequence of US withdrawal, stacked things against this vision. The Western powers now needed the USSR (which had been attacked earlier that summer by its erstwhile German ally) to defeat Hitler.

Thus, US thinking about Central Europe’s place started shifting. Journalist and author Walter Lippmann, the United States’ foremost foreign policy thinker and co-author of the Fourteen Points, argued as early as 1943 that the United States would have to underwrite the post-World War II peace after Germany’s defeat, and could not again withdraw from Europe. He also argued that the United States would have to maintain the peace in concert with the other great powers, including the USSR. According to Lippmann, that meant that Soviet interests in Eastern Europe would need to be respected; peace would depend, he wrote, on “whether the border states will adopt a policy of neutralization, and whether Russia will respect and support it.”3Walter Lippmann, US Foreign Policy (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1943), 152. It is not clear whether Lippmann understood what “neutralization” —meaning ceding hegemony to Moscow— would mean when interpreted by Stalin.

This was the first major US expression of a “realist” option for Central Europe based on spheres of influence. It assumed that the Atlantic Charter applied only to Western Europe, rather than all of Europe. This was the intellectual foundation of Roosevelt’s tacit acquiescence at Yalta of Soviet control of Poland and, by extension, the rest of Europe’s eastern tier of countries. This thinking continued throughout the Cold War, famously exemplified by President Richard Nixon’s framework of détente with the Soviet Union, which tacitly accepted Soviet control of the “Eastern Bloc” in exchange for a general relaxation of tensions and strategic stability. This was the best deal the Kremlin ever got from the United States during the Cold War.

The Yalta axioms—basing general European peace on recognition of Kremlin domination of its neighbors—are the strategic alternative to the Fourteen Points and the Atlantic Charter. The first reflects traditional great-power politics; the second represents the larger US grand strategy of a rules-based world favoring freedom.

Return to the grand strategy of freedom. The Yalta axioms of a divided Europe, consolidated in Nixon’s détente, turned out not to be the final word. Even under conditions of détente, Soviet communism did not work economically and, without economic success, could not build political legitimacy—especially in Central Europe, where it had little or none to start with. The Helsinki Final Act and CSCE process, and President Jimmy Carter’s human-rights policy, injected values back into the US approach to Central Europe.4The Helsinki Final Act, or the Helsinki Accords, was a non-binding agreement between thirty-five countries signed on August 1, 1975, that set standards for regional security as well as economic and humanitarian cooperation. The Helsinki Accords now have fifty-seven signatories and laid the groundwork for the formation of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). The CSCE process refers to the development of the Helsinki Final Act at the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in the early 1970s, where representatives from the original signatory countries met for two years to develop standards of cooperation between Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and their respective allies. Dissident movements in Central Europe and the first Solidarity in Poland (in 1980–81) challenged the assumptions that Yalta Europe, even under détente, meant a stable Europe. One unanticipated consequence of détente was that Western students, scholars, human-rights activists, and journalists came to know Central European dissidents, making Central Europe less of a gray abstraction.

In the wake of Solidarity, President Ronald Reagan turned US policy back to the framework of the Fourteen Points and the Atlantic Charter, just as Soviet communism was entering its terminal decline. Reagan’s insights held that the United States’ interests and values were ultimately indivisible, and that security was not ultimately compatible with Soviet domination of one-third of Europe.

Facing economic stagnation, Soviet Communist Party General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev concluded that the Soviet system needed major reform to survive, and this had a foreign policy corollary of outreach to the West. Under these new circumstances, repeats of the Hungarian repression of 1956 or martial law in Poland in 1981 were less viable options for him. Reagan was willing to work with Gorbachev on this basis, while still rejecting the Yalta axioms of Soviet domination of Central Europe.

Under these new conditions, starting in 1989, Central Europeans overthrew communism. After Reagan set the policy stage, President George H. W. Bush committed the United States to support the Central Europeans as they ventured onto new ground. The initial stages of post-communist transformation were fraught. As Polish leader Lech Walesa noted, communism was like turning an aquarium into fish soup: no special skill is required. Building democracy after communism, however, was like turning fish soup back into an aquarium: harder to manage.

Central Europeans’ success—sometimes spectacular success—in the democratic, free-market transformations that followed set the stage for strategic transformation. After fierce internal debate, President Bill Clinton set aside the Yalta axioms and, with Republican Party support, committed the United States to consolidate freedom’s advance in Europe along the lines of the Fourteen Points and the Atlantic Charter, working throughout with key allies in Western Europe, especially Germany. President George W. Bush, with Democratic Party support, continued this approach.

Through parallel NATO and EU enlargements, a Europe whole, free, and at peace expanded to include Central Europe. Central Europeans generated the political capital for this achievement through the steady success of their reforms and, at key moments, applied political pressure when the world reputations of leaders such as Lech Walesa and Vaclav Havel were at their peak. Though it remains a work in progress—as the Georgians and Ukrainians rightly point out—Central Europe’s long and difficult road of the twentieth century ended, as former Polish dissident and Solidarity activist Adam Michnik put it once, like a Hollywood movie: with an improbably happy ending.

What’s gone wrong?

The great achievement of a united Europe allied with the United States—and, thus, the core of a world democratic community—is at risk, beset with pressure from emboldened authoritarians and doubts from within. This is true on both sides of the Atlantic and in all parts of Europe.

Causes include: economic stresses, including persistent unemployment and slow growth (especially in parts of Europe); extreme and widening income disparities (especially in the United States); the decline of traditional industries and rise of new ones, generating new sets of relative winners and losers; and uneven benefits of trade. Structural weaknesses of the euro and economic differences between Europe’s north and south currently seem to be in remission, but may return.

Issues of national identity are another source of internal stress. This has been triggered in the United States by an influx of asylum seekers and would-be immigrants, especially from Latin America, and in Europe by the same categories of people from the Middle East and North Africa, exacerbated by anxieties about radical Islam and problems with newcomers’ integration into their receiving societies. In the UK, concerns about immigration also seem to apply to people from Poland and others from the EU’s eastern tier of countries.

In the United States, years of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have fed dissatisfaction with the consequences of US leadership and commitments in the world.

European and US publics often regard established political parties and leaders as having failed to cope with these challenges, and this has generated unusual—and sometimes extremist—political parties, candidates, and policies. As a result, the world’s democratic core is experiencing its worst period of internal doubt and dissension since the 1930s. Russia and China—aggressive and ambitious autocracies in their own fashion—may feel empowered to take advantage of this moment, and may even convince themselves, as did the dictators of the 1930s, that their time has come.

US leadership in question

The US version of these trends in the Donald Trump administration includes a political reaction of nativism, unilateralism, and a style of disruption, including skepticism about a rules- and values-based order underwritten by American power. The US political right of the Reagan era, which embraced freedom as a foundation of a US grand strategy, is being challenged today by a political right that draws on the language and sentiments of the nativist unilateralism of the 1930s (e.g., “America First”). Some of the nativist right’s rhetoric about Latino and Muslim immigration—including from President Trump himself—recalls the US nativist right’s anti-immigrant rhetoric from the 1920s. In parallel fashion, some on the US political hard left seem to share some of the hard right’s views about limiting US international leadership.

President Trump and some in his administration have expressed hostility to the European Union on the (false) grounds that it was established to damage US economic interests and supposedly represents a “globalist” transnational ideology harmful to US interests. President Trump has publicly—and, reportedly, privately—expressed skepticism about the value of NATO. If such politics turned into policy, the consequences would devastate the US grand strategy, erasing the lessons of two World Wars and the Cold War with terrible consequences.

Happily, the Trump administration has not acted on the most extreme elements of its rhetoric. Under President Trump, the United States has built on the Barack Obama administration’s support for strengthening defense of NATO territory against potential Russian aggression, including through US rotational deployments to Poland and support for UK, German, and Canadian-led NATO battlegroups in the Baltics, and by encouraging Europeans to invest more in NATO (while President Trump’s rhetoric can be seen as anti-NATO, his recommendation for more defense spending would strengthen it). The United States has at least started to work through trade issues with the EU Commission, and has maintained US-EU sanctions against Russia for its aggression against Ukraine. The administration’s National Security Strategy, produced under the leadership of former National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster, makes a credible case that the world has re-entered a period of great-power competition (in terms of Russia and China), and suggests that alliance with Europe (including through NATO), with greater burden sharing (especially for defense), can help address the challenge.

Nevertheless, US political distraction and flirtation with neo-nativism and unilateralism have opportunity costs, and could lead to greater dangers as Russia and China seek to challenge the rules-based, values-based world that the United States led in building.

Central Europe’s challenge of history and transformation

Shadows of the past. Where is Central Europe today?

Central Europe is living through its own version of the turbulence shaking democracy in Western Europe and the United States. Central Europe’s vulnerability is more pronounced, however, given its lower levels of prosperity, shorter tradition of democratic institutions, and profound legacy of communist misrule. Central Europe’s difficult history and ongoing transformation weigh heavily on it.

History in Central Europe is never far away. Behind its democratic, free-market transformation lie unfinished debates concerning wartime collaboration with Nazi Germany, as well as the special services and communist regimes, anti-Semitism, and old national and regional conflicts that have re-emerged and are piled onto the contemporary challenge of defining Central Europeans’ place in the enlarged European Union.

After 1945, Western European societies had two generations to work out issues of patriotism, nationalism, and the complex realities of their national behavior in World War II. Forty years of communist rule deprived Central Europe of that opportunity.

Though there were successes, the shock of transition from communism to democracy was great. The benefits of economic transformation have not spread evenly across society; even if all gained, some gained much more than others. While big cities Westernized quickly, provinces were sometimes forgotten in the reformist push of the 1990s to dismantle communist structures, deregulate, and adopt EU standards wherever possible.

Today, with the reality of freedom of movement in the Schengen zone, travel allows people to experience the prosperity in other EU countries that is lacking in their own. Many express frustration with their own countries’ conditions, and blame their own political establishments for the persistence of significant gaps in living standards. Moreover, many who were part of the old communist regimes prospered under the new ones, their earlier collaboration notwithstanding, adding to the sense of injustice many feel today.

Extremist populism in Central Europe, thus, should not come as a surprise. Since France and Germany have it, why not Hungary and Poland? Moreover, in Central Europe, constitutional norms are less enshrined in political cultures. There is less of a backstop against political leaders who make empty or irresponsible promises and are ready to change the rules of the democratic game, putting pressure on independent media and judiciaries. The middle class, with its default preference for moderation, is less established. Mainstream political parties often have an ephemeral existence. The region’s welfare states tend to have a smaller capacity to provide opportunities for the poor.

The facts are stark: despite good, and sometimes massive, economic progress during the past generation, Central Europeans will need at least thirty or forty more years to reach Western European levels of prosperity. People may look for leaders who offer shortcuts to mend broken public policies, secure rapid economic growth, and “restore dignity.”

This last factor plays an important role: people understand dignity as the freedom to choose social models and standards perhaps different than those prevailing in contemporary Western Europe. Those societies are ecologically minded, tolerant toward sexual orientation, and sometimes pacifist—the result of decades of harmonious growth under security provided, in large part, by the United States. Central Europeans, who overthrew communism in the name of democratic but also national values, sometimes have a different mindset: more socially conservative, more defensive about national sovereignty, and more protective of national values, often interpreted in a conservative light. This may help explain some of the anti-EU and anti-German posturing, and the careless use of irredentist rhetoric that casts a shadow over Europe.

Central Europes’s geopolitical context

Central Europe’s neighborhood remains challenging. Gone is the mix of hope and disappointment of Boris Yeltsin’s era in Russia. Vladimir Putin’s Russia is resurgent, assertive, and revisionist. Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia are struggling to develop resilient democracies built upon successful economic models. To block their Western future, Russia has attacked Ukraine and Georgia, invading and occupying their territory. While Georgia’s and Ukraine’s reforms are impressive, they have not yet achieved the critical mass necessary to decisively escape the post-Soviet model of governance. Central European governments have kept Eastern Europe high on the EU agenda, but neither Europe nor the United States have decided how, or even whether, the West can incorporate Eastern Europeans into its structures a s it did with Central Europeans.

Having said this, Central Europe has never had it so good. With no foreign claims on its territory and Russia’s potential threat mitigated by nations’ membership in NATO, the region seems to have finally broken free from its curse of horrific geopolitical conditions and domination by outside empires. Relatively secure in Europe, Central Europeans are at last able to build ties with the United States in a mature way: as partners in Europe and beyond, not as supplicants. To do so, they will need to draw on their best traditions, the ones that propelled so much success in 1989, and for a generation thereafter.

The United States as seen from Central Europe

The thirteenth-century Spanish King Alfonso X once remarked, “Had I been present at the creation, I would have given some useful hints for the better ordering of the universe.”5“Present at the Creation,” Economist, June 29, 2002, https://www.economist.com/special-report/2002/06/27/present-at-the-creation.

Central Europeans have long invested great hopes in the United States. But, whether Central Europeans like or not, the United States is no longer the uncontested superpower; rising and revisionist powers are nipping at its heels. The United States and its allies, including Central European countries that still count on US power, must live with this. Central Europeans have noted that the United States has been shifting from an overwhelmingly European ethnic base to a more global population. The number of Americans with roots in Europe (and Central Europe specifically) serving in US administrations has been decreasing. Politicians vying for support of ethnic minorities in the United States once focused great attention on the Central European-American communities (particularly those from Hungary and Poland in the Northeast, or from Czechia in the Southwest); now they concentrate on larger groups.

Transatlantic relations, and the US leadership on which they rest, are not doomed to a downward spiral, but much depends on two US characteristics. The first is the United States’ readiness to practice what it preaches. Deeds should follow words. If the United States says it favors free trade, it should not readily slap tariffs on imports from its friends. If the United States says it favors democracy, it should not tacitly support dictators or shut its eyes to authoritarian trends. The second indispensable trait is the United States’ proven ability to adapt to new challenges, and even to reinvent itself. At its best, the United States has found ways to reverse its mistakes and return to its best traditions. Americans, like Central Europeans, must draw on their own best traditions to deal with present dangers.

Addressing weak points of the current US strategy toward Central Europe

A successful track record of cooperation and a wide scope of common interests have allowed some Americans and Central Europeans to forget that their work is not yet done. The integration of Central Europe into Western institutions, while well embedded in the minds of most Americans and Europeans, must be maintained.

However, some Western European and US assessments of trends in Central Europe are shallow, reflecting misunderstandings of local dynamics and worst-case-scenario projections of the future. As in the United States and Western Europe, political stresses in Central Europe are generating problematic political flirtations in some countries. These include indulgent anti-EU or anti-German rhetoric, careless use of irredentist language, and pressures on independent institutions both within and outside of government, such as the courts and media. Sometimes-rocky relations between the EU Commission and some governments from the region, coupled with growing feelings of disenfranchisement within the EU, pose additional challenges.

In order to successfully reverse these trends and build on the positive aspects of the current US strategy toward the region, four specific areas of concern need to be addressed.

First, the lack of concerted effort to take into account Central Europe’s regional security sensibilities. The United States, through several decades of disengagement from Central Europe and an attitude of “mission accomplished” (specifically on issues of free markets or institutional development) often gives the impression to many in the region that Washington does not wish to remain engaged, and that Central Europe must fend for itself. Democratic institutions in the region are still comparatively weak due to their relatively short period of existence and the geopolitical realities in which they operate. There is a desire for a stronger US presence in the region, at both the governmental and nongovernmental levels. US failure to understand the security environment in which Central European democracies must function and support the development of these democracies, at all levels of society, is a costly miscalculation.

Second, US ambivalence toward the European integration project. Central Europeans should never be forced to choose between European integration and partnership with the United States. Similarly, the United States should take into account that bilateral relations with specific member states should not come at the expense of multilateral formats such as US-EU dialogue. Disruptive rhetoric—for example, in support of the Brexit agenda—is perceived as anti-EU. Some in Central Europe might see this as an opportunity to advance US-Central European relations, but such advancement must not happen to the detriment of the European project. Europe, including Central Europe, is an important economic and ideological partner of the United States, and an integrated, successful European Union will only benefit US interests.

Third, the growing neglect of Europe’s strategic importance, more broadly. The continuing shift of US attention and resources from Europe toward Asia has not gone unnoticed, and has alienated some within Central Europe for whom the United States is still an important partner. Many in the region believe the frequent anti-EU and anti-NATO rhetoric used by President Trump is simply a theme of the current administration and will dissipate with a new president. This should not be assumed, however. Neither Europe nor the United States can withstand the growing global economic or ideological competition alone. The European Union is a critical partner for the United States, and a shared transatlantic approach will strengthen the ability of both sides to maintain the principles of the democratic and free-market world order.

Lastly, failure to persevere in supporting Ukrainian and Georgian freedom and Euro-Atlantic integration. Abandoning efforts to extend the West’s institutions to Europe’s eastern neighbors could have unintended consequences in Central Europe. Not only are Central Europeans vulnerable if NATO security guarantees are no longer deemed sacrosanct by the Alliance’s adversaries, but an unprincipled reset with Russia and acquiescence to Moscow’s illegal territorial gains in Ukraine and Georgia could be interpreted as tacit acceptance of a sphere-of-influence arrangement. Resisting spheres of influence is, first and foremost, about imposing costs on Russia and supporting Ukraine and Georgia, politically and economically. Even if Europe underperforms in terms of increasing its military expenditure, on the whole, Europeans are investing more in their own defense. No shadow should be cast on the United States’ loyalty and willingness to defend its allies and the principle of an undivided Europe, whose institutions extend as far as its values. The need for cooperation, especially related to hybrid and cyber threats, has never been greater, and Central Europeans are at risk. Visible commitment to the sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity of Ukraine and Georgia—and their Euro-Atlantic future—are important pieces of US strategy.

Despite these challenges, the current state of the US strategy in the region remains sound, and its more problematic elements are reversible. Nevertheless, the United States needs to reevaluate some aspects of its current approach to the region. While Central Europe’s national interests and major strategic goals are, in fact, likely to keep the region in the Western community, there will inevitably be some variance among countries in terms of how actively they are involved in various institutions. Even so, it should be the United States’ goal to keep Central Europe firmly integrated in the Western democratic order.

What, then, must the United States and Central Europe do?

Following Central Europe’s accession to NATO and the European Union, many on both sides of the Atlantic concluded that the United States’ work (and special role) there was done. This was not so.

While Central European countries are institutionally part of the West, in some cases (e.g., Hungary and Poland) those ties, especially with respect to the European Union, have come under stress. At the same time, Putin’s government is using disinformation, energy, corruption, and other forms of pressure to exploit these differences and weaken these bonds, seeking to decouple Central Europe from Europe and the United States, part of its larger strategy of weakening the West. As a result, the great achievement since 1989—of a Europe whole, free, and at peace, with Central Europe an integral part of it—is again in play, and possibly at risk.

This paper recommends an action plan for the United States and Central Europe, as they start their second century together, sorted into baskets of democratic values and politics, security, and economics. The specifics should reflect longstanding and shared strategic objectives: Central Europe has, over the past one hundred and one years, sought a secure and inalienable place within Europe as a whole, while regarding the United States as a champion of its cause. The United States, at its best, likewise regarded Central Europe as part of an undivided Europe, while regarding Central Europeans as natural partners and allies. Both, at their best, have understood that security, prosperity, democracy, and the rule of law were indivisible. That common strategic vision has guided the Central European-American partnership, now an alliance, and should continue to do so.

Democratic values and politics

Democratic values have been at the heart of US-Central European relations since 1945. The Central European dissidents who succeeded in 1989 resisted communism, in the name of both national patriotism and universal democratic values, and the United States ultimately supported them for the same reasons. The successful democratic reforms in Central Europe after 1989 generated the political capital necessary for NATO and EU enlargement.

Conversely, the relationship will fade (and Russian and Chinese goals will advance) should the most negative trends continue and Central Europe’s democratic transformation falter or degrade. The worst case would include deterioration into what might be termed “plebiscite authoritarianism”—a system democratic in form only, with economic power increasingly in the hands of state-controlled companies and mini-oligarchs; a return to government- or ruling-party-dominated media; and an authoritarian and nationalist political culture.

If this became the reality in most, or even a significant number of, countries in Central Europe, the political underpinnings of the US commitment to Central Europe would be weakened and, simultaneously, Central Europe’s standing with the rest of Europe would decline. A split over values would weaken the EU and even NATO. In such a situation, the Kremlin could take up its desired role as an off-stage, controlling presence, exercising influence through corruption, disinformation, and use of energy and other forms of economic leverage. The Chinese could do the same, to a lesser extent and using primarily economic tools.

US and Central European leaders, in and out of government, must find ways to address issues of democratic values in more productive ways than has sometimes been the case in recent years. This paper recommends the following actions.

The United States should pick its “democracy issues” carefully. Media freedom, judicial independence, and the rule of law generally—to which all Central European governments are already formally committed—should top the list of US concerns. Issues such as abortion rights, other social issues, historical issues, or immigration/migration, may not be on top of the list. If the United States seeks to take on everything, it may succeed at nothing.

Tactics for addressing the issues of the rule of law and democratic governance will vary. Expressions of concern, especially strong ones, should usually be delivered confidentially. In some cases, however, public messages will be needed. A US public narrative should be framed to put the United States on strong ground for the expected counter-charge of “foreign interference,” by rooting democratic values in terms of shared history, values, and the struggle against communism. The Western tradition—including the Enlightenment and older Christian traditions—qualifies sovereignty by positing that even a king is answerable to higher standards. The US public narrative could also emphasize that a strong, modern state has strong, independent institutions; a politicized state that allows for “telephone justice” is, in fact, a weak state.

The United States cannot be shrill or impatient. Lecturing from a distance and finger wagging are unlikely to produce good results. Restricting bilateral dialogue as attempted leverage, which the US government attempted with respect to Hungary under the Obama administration, led to anomalous outcomes, such as when the US secretary of state would eagerly meet his Russian counterpart while refusing to meet his Hungarian counterpart.

The United States must be persistent. It should make its points about the rule of law and democracy so consistently that the United States becomes branded as a force for higher principles, and one with enough sophistication to maintain a reputation for knowing the facts, rather than being stuck in abstractions or exaggerations. The United States should resist transactional trade-offs that require ignoring problems with the rule of law in return for favors in other areas.

US and Central European leaders should avoid being drawn into the other’s partisan politics. This elementary diplomatic lesson bears repeating: democracy is not the same as political identity.The United States should have no partisan preferences in Central Europe, but should focus on common values and strategic interests, working with a wide spectrum of groups and parties to advance them. Central European leaders, especially on the right, should similarly avoid overinvesting political capital in their presumed US ideological counterparts. This problem is mutual, because some individuals in or close to the Trump administration have sought to advance a rightist, partisan agenda as an organizing principle of US policy toward Europe.

US and Central European governments should create an unofficial or “track 1.5” process to address issues of democratic politics and values. Given polarized politics in both the United States and Central Europe, a track 1.5 process (a mixed official/unofficial dialogue involving governments and selected nongovernmental experts) may be a productive way to address these issues. The purpose would be to help identify common ground, avoid mischaracterizations, and avoid cycles of recrimination and polarization. Such a process could, for example, seek to define the common values of the transatlantic community in ways that include a wide spectrum of political views consistent with democratic fundamentals.

A dialogue could address challenges to the integrity of institutions, both in and out of government, essential to the functioning of a modern, democratic country. This could include the roles of the media and judiciary, financial and regulatory transparency, and other aspects of a common tradition of independent branches of government. Such a dialogue also could take up complicated issues such as national identity, the nature of patriotism and nationalism, and the role and perception of these concepts in both US and European history. The United States could also use such dialogue to further support “horizontal” ties between US and Central European institutions, e.g., think tanks, the judiciary, universities, and students.

The United States needs to underscore the critical place democratic values have in its relations with Central Europe, but without partisanship or lecturing. Central Europeans need to recall that their claim on US support was their linkage of national patriotism and universal democratic values.

Security

Central Europe’s integration into NATO and the EU put the region’s overthrow of Soviet rule on a solid institutional footing. Within Central Europe, NATO and EU memberships were regarded as part of a strategic whole. As Central Europeans argued at the time—accurately, as it turned out—NATO membership supported economic development and reform in Central Europe, conveying to Western investors that these countries were secure. Through their conditionality (general for NATO, and detailed for the EU), both the NATO and EU membership processes helped stabilize democratic politics through the most difficult years of systemic transformation.

At the same time, for twenty years after the end of the Cold War, even as NATO grew, the United States drew down its forces in Europe, and many European countries allowed their militaries to decline. The United States regarded Russia as a potential partner, rather than a threat, and did not fully reassess its assumptions even after Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia. Indeed, the United States did not fully heed prescient early warnings about Russian intentions from the Poles, Baltic governments, and others in Central Europe. The United States and its allies shifted their military focus to the “war on terrorism” and efforts to transform the Middle East.

Only after the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine did NATO reassess its assumptions. Through decisions made at three post-2014 NATO summits (Wales in September 2014, Warsaw in July 2016, and Brussels in July 2018) NATO started increasing the strength and readiness of its deployable forces, and began to deploy forces to the Baltic states and Poland as a form of deterrence against potential Russian aggression. Now, the British lead NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) battalion in Estonia, the Canadians lead in Latvia, and the Germans lead in Lithuania. The United States leads a NATO eFP battalion in Poland, stationed near the Suwalki Gap, and has also stationed an armored brigade in Poland on a rotational basis. Central Europeans are doing their part; in 2019, five countries are meeting the 2-percent-of-GDP benchmark for defense spending, and others are approaching this target. This welcome progress may not, however, be enough to deter Russian aggression or intimidation.

Underlying perceptions in Central Europe

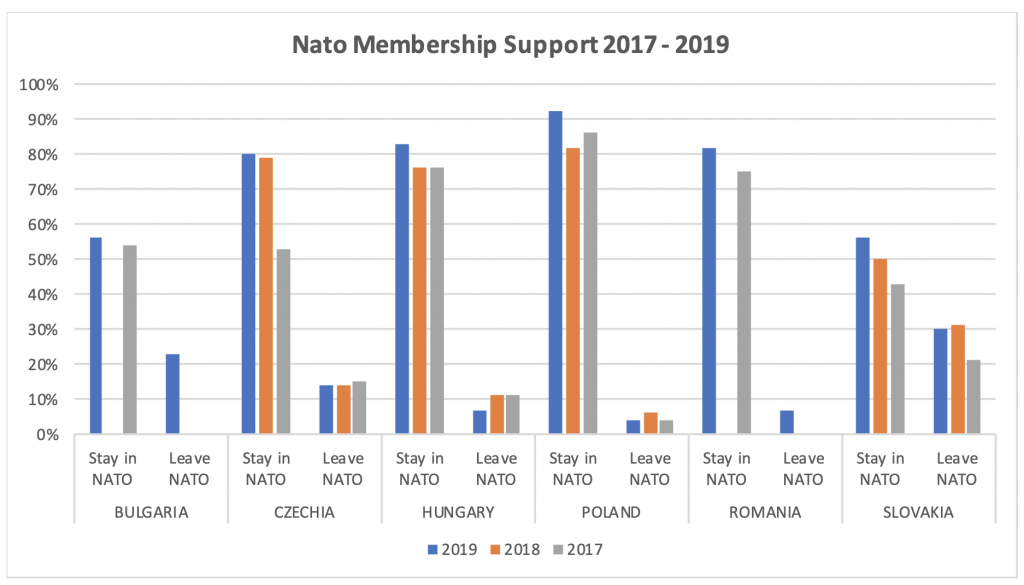

Support for NATO membership, as well as for US leadership, varies significantly in Central Europe, reflecting each country’s historical experience and tradition. Views of Russia as a threat also vary markedly between countries, with Poles and Romanians the most apt to regard Russia as a threat, and Bulgarians and Slovaks the least. The differences notwithstanding, GLOBSEC Trends 2019 data show two important patterns (see graphs further down).

- Even in the Central European countries with strong economic, cultural, or historical links to Russia, twice as many people support NATO membership as oppose it.

- The share of NATO supporters has been growing in Central Europe since 2017, including a 27-percent increase in Czechia, 13 percent in Slovakia, 7 percent in Romania, 7 percent in Hungary, and 6 percent in Poland. Increasing public support for NATO membership can be attributed to an increase in instability in Central Europe’s neighborhood, as well as instability in the Middle East and successful communication efforts such as the #WeAreNATO campaign.

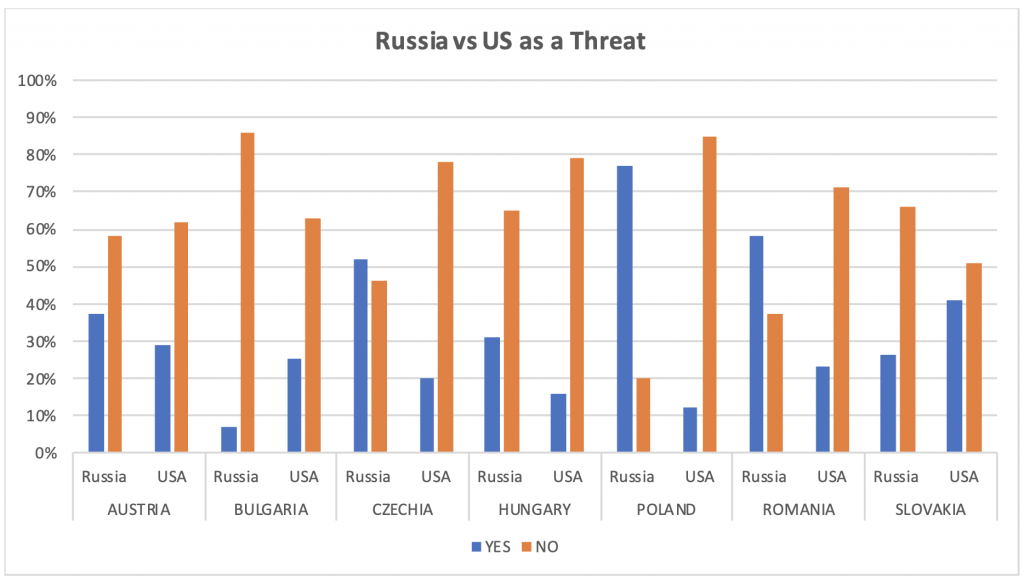

But, alongside growing support for NATO, there is a worrying trend in some Central European countries—possibly related to Russian disinformation—of negative perceptions about the United States. Although all the countries in the region are members of NATO, 23 percent, on average, see the United States as a potential threat.6Dominika Hajdu, Katarina Klingova and Daniel Milo, GLOBSEC Trends 2019: Central & Eastern Europe 30 years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, GLOBSEC, June 2019,https://www.globsec.org/publications/globsec-trends-2019/. Worse, more people in Bulgaria and Slovakia believe that the United States presents a greater threat to their country than does Russia.

These trends are not taking place in a vacuum. The Russian government currently employs a full spectrum of hybrid-warfare tools to sow doubts about NATO and the United States, using energy dependence, economic ties, business opportunities, cyberattacks, strategic corruption, information campaigns, or direct support to Russia-friendly political actors and parties. The Kremlin uses its assets to target specific vulnerabilities: Euroscepticism and migration, protection of so-called “traditional values,” disillusionment with the state of economic development, shortcomings of post-1989 transformations, ethnic and historical disputes, conspiracy theories, or open anti-American sentiments. Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia appear particularly susceptible to Russian disinformation campaigns and other forms of pressure.

Security issues again matter in Central Europe; Putin’s Russia has become a real and enduring threat. To strengthen US-Central European security relations, this paper recommends the following.

The United States should raise its public profile on security in Central Europe. Without increased US presence, through high-level visits (executive and Congress) and through think tanks and other nongovernmental organizations, Russia can continue to exploit the information space in Central Europe. Furthermore, if negative perceptions of the United States in the region remain unchallenged, such trends may continue to rise and, in the short term, undermine NATO’s principle of collective defense, while causing greater harm in the long term.

To improve the United States’ public profile, this paper first recommends that the United States and Central Europe intensify their official military and security dialogue throughout Central Europe, both bilaterally and multilaterally. The military and security dialogue should rest on the assumption that NATO will remain the major instrument of common security. One example of how the United States could signal such leadership is by sending a high-level representative to high-level meetings of the Bucharest Nine format (the Baltic states, Visegrad countries, and Romania and Bulgaria) and to Nordic-Baltic defense ministers’ meetings.

The United States should remain engaged in European security—not only through the institutional frameworks of NATO, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), or its bilateral partnerships with particular countries, but also as a constructive partner of the European Union in its efforts to foster closer cooperation among its members on defense. The United States should, directly or through its likeminded allies, approach the process of European defense integration and, where necessary, constructively point out the issues where EU processes like the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Defence Fund risk creating duplications or reducing the overall defense readiness of NATO.

Next, the United States should support greater public outreach in Central European countries. Bilateral US security relations and arrangements with Central European countries should not be seen as replacement or circumvention of NATO, but as an addition. Maximum possible transparency regarding US plans and goals is necessary to avoid creating the impression that the United States wants to organize the defense of NATO’s eastern border without full knowledge or buy-in of the countries involved. The United States should also publicly address false, but widespread, concerns that US security interests in the region are driven by interest in major defense contracts. Sustained public efforts will boost Central Europe’s support for a strong response to the re-emerging Russian security threat and give the United States an opportunity to improve its brand.

Finally, this paper recommends an increase in cooperation between US and Central European nongovernmental organizations and think tanks. These would bolster productive public conversations about NATO and collective security, while drawing upon the research and the wide network of expertise that nongovernmental organizations produce.

The United States and Central Europe should intensify (hard and soft) cybersecurity cooperation. Central Europe, like the rest of the Europe and the United States, has faced technical and disinformation attacks from the East. This includes an attack on the Slovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs in October 2018, which the prime minister attributed to foreign actors. In the same month, the Slovakia-based ESET, an information-technology (IT) security company, released a report outlining the malicious activities of a hacker group against Polish and Ukrainian energy and transport companies.7Anton Cherapanov, GreyEnergy: A Successor to Black Energy, ESET, October 2018, https://www.welivesecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ESET_GreyEnergy.pdf. That group, Sandworm, has been accused by the British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) of having ties with Russian military intelligence. There is also evidence of interference in election processes, both against technical electoral infrastructure (data breaches in voter-registration databases, tampering with voter data, and defacement, denial-of-service, and attacks on websites while communicating results etc.) and spreading disinformation. Despite the threat, regional cooperation in cybersecurity has been inadequate.

Central European capacity and resources to combat cyber threats vary by nation. Poland continues to heavily invest in its cyber defense capabilities, having recently announced plans for a new cyber defense force, and Estonia is known for cyber sophistication. But, Slovakia and other countries still heavily rely on NATO membership and collective cyber defense. The United States, and NATO in general, must respond to the challenge of the differing and fragmented cyber capabilities of allies to build strong cyber deterrence and, eventually, active cyber defense.

Cyber vulnerabilities also arise from an overall lack of social and individual awareness about cybersecurity: unwitting or careless users continue to be the number-one vector for attackers to penetrate networks. Unprepared and cyber-naive workforces and populations, therefore, continue to be one of the biggest obstacles to securing digital economies and infrastructure. Investment in social awareness and resilience may prove at least as effective as short-term cyber defense.

In parallel, the United States and Central Europe should, working with the EU, combine efforts to expose Russian disinformation campaigns. Many techniques to combat disinformation, such as tools to introduce new standards of transparency and integrity on social media (e.g., exposing and removing inauthentic accounts or impersonators) may be developed by EU (and US) regulatory bodies, perhaps supported by law enforcement. One area for tailored US and Central European cooperation may be support of their respective civil-society groups—those so-called “digital Sherlocks,” or bot and troll hunters—which have a proven capacity to expose Russian and other disinformation campaigns to the public. Russian efforts to exploit long-standing social, ethnic, and racial divisions are likely to be as present in Central Europe as they have proven to be in the United States, and exposure of Russian disinformation efforts to support extremists may help discredit them.

The United States and allies in Central Europe should work bilaterally to strengthen deterrence on NATO’s eastern flank, complementing and reinforcing what is taking place within NATO. NATO’s forward stationing of forces, along with US forces, in the Baltics and Poland, and the establishment of two Multinational Division HQs (Northeast in Poland and Southeast in Romania) are welcome, but only a start. Given the capabilities of Putin’s Russia and its demonstrated willingness to commit aggression in Europe, this paper recommends that US allies on the eastern flank work together to increase the West’s military deterrent capacity, as the United States is discussing with Poland. The purpose would be to demonstrate to Russia that it cannot hope to mount a sudden assault on NATO countries—either with conventional forces or through hybrid means—without triggering a much wider conflict.

The Atlantic Council’s recent study on “permanent deterrence” outlines a useful combination of increased US permanent and rotational deployments and development of military infrastructure to support rapid reinforcement—in parallel with capabilities from other allies, “old” and “new” members alike, and all in congruence with NATO’s strategy of deterrence.8Philip Breedlove and Alexander Vershbow, Permanent Deterrence: Enhancements to the US Military Presence in North Central Europe, Atlantic Council, December 13, 2018, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/issue-briefs/permanent-deterrence-enhancements-to-the-us-military-presence-in-north-central-europe. This would increase coherence between allies, and would politically contribute to reducing tensions in Europe, including between western and eastern members within the European Union.

Additionally, the United States should strive to gradually align its bilateral military measures in Central Europe with those of NATO under the European Deterrence Initiative. Other allies, especially Germany and France, should be strongly incentivized to co-own these enhanced measures and contribute their personnel to defend the eastern border of NATO. This would increase coherence between the allies and, politically, contribute to reducing tensions in Europe and within the EU, between western and eastern members, and between old and new ones.

It is crucially important that Central European countries be engaged in efforts to increase the Alliance’s deterrent capacity. The means will vary.9Some recommendations for the way forward were also elaborated upon in the GLOBSEC NATO Adaptation Initiative’s 2017 report: Gen. John R. Allen (Ret.) et. al., One Alliance: The Future Tasks of the Adapted Alliance, GLOBSEC, November 27, 2017, https://www.globsec.org/publications/one-alliance-future-tasks-adapted-alliance/. Stationing forces in Poland and the Baltics has logic given geography, including those countries’ common borders with Russia (and Belarus). Other forms of US and NATO presence may make sense in other countries (e.g., Romania and Bulgaria), which face Russian forces operating in the Black Sea and potentially mounting new attacks on Ukraine. Strengthening NATO’s deterrence-and-defense posture, to prevent conflict and deter aggression by enhancing the readiness and responsiveness of NATO conventional forces, must be the overarching priority for all allies. US involvement on the eastern flank and enhanced effort of the eastern allies are indispensable to achieve this goal. While most countries in Central Europe are reaching, or are on the path to reach, the 2-percent threshold, better equipping and affording NATO and smarter spending should be joint priorities with the United States. With the case for enhanced European effort in the area of defense becoming overwhelming, all Central European countries are also willing to participate in ongoing closer cooperation within the EU, particularly in the framework of PESCO. The justified concerns about possible duplication of structures in the EU and NATO, and skepticism about prospects of European strategic autonomy, need to be addressed by a more ambitious and comprehensive NATO-EU partnership.10Ibid.

The United States may have neglected Central Europe’s security concerns after NATO enlargement, but is making up for lost time. Central Europe should take advantage of the opportunity, working with the United States and European NATO allies such as Germany.

Economics

At the start of Central Europe’s systemic transformation thirty years ago, its economic challenge was existential: whether the region’s communist economies, then in various states of stress or collapse, would be able to grow at all. Most experts in the West were betting against it. Desperate to re-start their economies, the new democratic governments introduced free-market reforms. These worked. The more radical reforms—implemented by Poland, and later the Baltic states and Slovakia—were generally the most successful, with results ranging from good to spectacular (Polish, Baltic, and Slovak gross domestic products (GDPs) roughly tripled in less than thirty years). State-owned banks and enterprises still play a large role in the region, however.

Central Europe’s most profound reforms and the shift to rapid growth took place before EU membership, but were supported by the prospect of EU integration and the reforms required along the accession path, which strengthened economic institutions and rules including around property rights. When it came, EU membership deepened and extended the region’s economic development, especially in the relatively poorer countryside. Central Europe’s economies are today integrated with the rest of Europe, and are likely to remain so. Germany, particularly through its automotive industry, has an outsized impact in the region. German-Polish trade, for example, is greater than German-Russian trade (a fact not always appreciated, including by many Germans).11“Poland Now Germany’s Most Important Trade Partner in Eastern Europe,” Deutsche Welle, February 27, 2014, https://www.dw.com/en/poland-now-germanys-most-important-trade-partner-in-eastern-europe/a-17463227. Central Europe’s economies, at last part of the giant European and transatlantic economy, are poised to move up to a next level of wealth and sophistication, reflecting the original intent of US and Central European policymakers starting in 1989.

This has brought enormous benefit to Central Europe, along with new challenges. One such challenge comes from an EU coping with Brexit and other internal issues. EU structural funds available for Central Europe have spurred development (as they did for Spain and other earlier EU entrants), but economic infrastructure in Central Europe remains far behind that in Western Europe, and EU structural and other funds are likely to drop in the mid-term, as Brexit may put downward pressure on the EU budget. Freedom of movement within the European Union has opened opportunities for young people from Central Europe, but also exacerbated a brain drain of talented youth.

At home, Central European economies face challenges from the risk of systemic exercise of political influence over the economy—applied through the large state-owned banks and other enterprises—potentially crowding out other, perhaps more creative and entrepreneurial, business actors. The region also faces external challenges, including from Russian pressure (and corruption); valuable, but sometimes problematic, Chinese investment, which brings political strings and security concerns; and an inward-looking United States with a protectionist agenda.

Russia still provides most of Central Europe’s oil and gas (especially the latter) and has demonstrated its willingness to use energy as political leverage. Russia’s share of Central Europe’s trade in oil and gas is beginning to decline, the Nord Stream gas pipeline project notwithstanding, but slowly. In overall trade, however, Russia has become a secondary player. In Hungary and Poland, for example, US and Russian levels of trade are roughly the same, even including energy.12“Russia,” Observatory of Economic Complexity, accessed April 2, 2019, https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/rus/; “United States,” Observatory of Economic Complexity, accessed April 2, 2019, https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/usa/. Given Russia’s geographic proximity and economic domination throughout the Cold War, Central Europe’s shift in one generation from Russian to Western economic orientation is remarkable. At the same time, as is the case throughout Europe and in the United States, Russia has established the practice of disguised (and, reportedly, frequently corrupt) investments in Central Europe, including in real estate, but also in and through financial institutions.

China has become a major trading partner in Central Europe (for example, the second-largest source of Poland’s imports, after Germany). Its investments are growing, promoted through China’s One Belt One Road initiative and, in Central Europe, the “16+1” initiative (sixteen Central and Southeast European countries plus China—now “17+1” with the addition of Greece). In Hungary, foreign nationals who invested significantly in the country, in large part from China, received residency permits.13“Hungary: Golden Visas Take New Form in Orban’s Government,” Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, last updated May 16, 2018, https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/8088-hungary-golden-visas-take-new-form-in-orban-s-government. Chinese practice in other parts of the world includes using investments strategically, seeking influence and political leverage; Chinese telecommunications investments (e.g., Huawei) have raised security concerns now being considered on both sides of the Atlantic.

The US economic role in post-1989 Central Europe was initially that of assistance provider, through expert advice (some excellent, some less so), debt relief, and infusions of capital and entrepreneurial training through government-sponsored enterprise funds. This helped the Central Europeans, especially Poland, through the most difficult period of economic transformation. By the mid-1990s, as Central European economies began to take off, US direct investment became (and remains) a significant factor.14“United States,” OECD International Direct Investment Statistics 2018 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1787/b859c708-en. Much of that investment is in high-tech, high-value-added industries, cyber, telecom, and energy. Though bilateral trade remains modest (it is comparable to Russian-Central European trade) there are natural opportunities for growth. The recently volatile nature of trade relations under the Trump administration, however, threatens this. Any potential trade war with the EU will have tremendous repercussions for Central Europe, given its linkages to the German economy: car-industry tariffs, for example, would hit many Central European economies hard, as many German manufacturers have operations in the region.

The United States can play a useful role with Central Europe in addressing these “next-stage” challenges. To do this, this paper recommends the following.

The United States and Central Europeans should use the “Three Seas Initiative” to accelerate the development of Central Europe’s infrastructure. The “Three Seas Initiative” (3SI) originated with parallel US and Central European ideas for thickening energy, transportation, and cyber infrastructure networks among post-1989 EU member states, and was championed by Polish President Andrzej Duda and Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović.15“The Joint Statement on The Three Seas Initiative” (statement presented at the 2016 Dubrovnik Summit of the Three Seas Initiative, Dubrovnik, Croatia, August 25, 2016). The Trump administration embraced 3SI, which became a substantive centerpiece of President Trump’s July 2017 visit to Warsaw (through a simultaneous Three Seas Summit there). Originally viewed with skepticism by the EU and German governments as a possible anti-EU, US “wedge” project, 3SI has developed into a uniting initiative, bringing together the EU and United States in support of common objectives, thanks in part to the Romanian role as host of the 2018 Three Seas Summit in Bucharest. Poland’s National Development Bank (BGK) has established an initial investment fund to support TSI projects. Identification of viable projects and funding for them will be the test of 3SI’s effectiveness.

If it were funded, 3SI could become a vehicle to address Central Europe’s relative infrastructure gaps in a time of declining EU funding, bringing together the region’s governments, the United States, and the EU Commission (a mechanism bringing the Trump administration and the EU Commission together in common purpose would be a major achievement). Though it was not the initial intent, 3SI could also be a transatlantic counterpoint to China’s 16+1 project. Southeast European countries not in the EU (Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, North Macedonia, and Montenegro) are also not included in 3SI, but are in 16+1. Chinese influence and debt diplomacy may be especially attractive to them. Their concerns and vulnerabilities will need to be addressed, perhaps by opening 3SI up to them in some fashion.

Finally, through its pillar on energy/pipeline infrastructure, 3SI could also mitigate Russia’s potential energy leverage over Central Europe by developing regional gas pipelines, reducing the importance of Nord Stream and its southern counterpart, Turkstream. Germany, which may seek membership or at least observer status in 3SI, may find it useful to support 3SI energy projects to offset Russian leverage, seeking to ease tensions with Poland and other Central European countries over German support for Nord Stream.

The United States and Central Europe should develop regular economic dialogues. These dialogues would gather the highest-level economic leaders from the public and private sectors to address the challenges referred to above, and would address a variety of topics.

One such topic could include dialogue on transparency and security in foreign investment. Foreign investment helped transform Central Europe’s economies after 1989 and will be a key factor in continued growth. But, good things can be badly used. The US government’s Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), in existence since 1975 and more active starting at the end of the George W. Bush administration, screens foreign investment in the United States against security and national-interest standards. While not directed explicitly at Russia or China, CFIUS is a useful tool for dealing with the general challenge of foreign investment as a strategic tool of the state, a practice of both governments. Despite some concerns, CIFIUS has not been politicized or used as a tool of protectionism. In March 2019, the European Union launched its own mechanism to screen foreign investment. Such an investment-transparency dialogue could be constructed as official-only, track 2, or track 1.5 (official/nongovernment hybrid, as recommended above). It could include all interested governments, but it might be more practical to start with a subset of countries and the EU.

The United States would bring both expertise and credibility to such a dialogue with Central Europe.For one thing, the United States has less baggage than some of the larger EU member states (German investment has sometimes been pilloried by the current Polish government, playing to historic memories). An investment-transparency dialogue could be a vehicle for exchanging best practices—and cautioning against pitfalls, such as arbitrary protectionism—in addressing the potential abuses of state-directed foreign investment (sometimes supported by corruption). Russian and Chinese investment would be a major topic. Additional topics could include issues of intellectual property rights (IPR) protection (a problem with China), means to enforce transparency (e.g., uncovering Russian investment that is hidden, for example, through layers of third-country-registered limited-liability companies or host-country shell partners or corporations).

Another topic could include business dialogues addressing cutting-edge opportunities (such as cyber) and the challenge of how to maintain an entrepreneurial edge given the power of state-owned large enterprises. The explosive growth of small and medium enterprises in the initial period of post-1989 reforms saved many Central European economies and propelled their steady growth for a generation. In Central Europe, as in the United States, the cutting edge of economic development in the twenty-first century will be similarly bottom-up and technologically forward-looking. Such dialogues should encourage cutting-edge business opportunities and pro-entrepreneurial policies, and address how economies characterized by large, state-owned banks and enterprises can maintain their entrepreneurial edge and avoid the traps of cronyism and politicization.

A third topic would be harnessing the financial industry to promote broad-based economic growth. Enhanced transatlantic dialogue between the public sector, international financial institutions (such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the European Investment Bank), and the financial-services industry could be used to promote policies that enhance financial inclusion and broad-based growth, including through innovative financing techniques and instruments such as green bonds (used to finance environmentally friendly projects issued by the private or public sector).

While Central Europe’s principal economic orientation will be with the rest of the European Union, the US-Central Europe economic dialogue can add value by encouraging infrastructure development, and improved investment and business practices. The US strength in value-added investment and relative lack of historic baggage continue to give it a major role to play.

Bottom-line recommendations

Beyond specific recommendations, the United States needs to “show up” in Central Europe with a broad agenda. The United States has played a special role in Central Europe for one hundred and one years. It still has influence, and needs to use it to advance a common cause of a united West, not give the impression that it has surrendered its strategic and historic interests there. As hard experience has taught, the United States should not treat Central Europe instrumentally, either as an object to be traded with the Kremlin or as a wedge against a strong and united European Union (a bad idea with which some in Washington occasionally flirt). On the contrary, the United States and Central Europe both gained most when they were working together with common purpose and in service of a big vision: to resist communism when the United States supported democratic movements in the 1980s, and to build a united Europe and an undivided transatlantic community after 1989.

Today’s common vision includes consolidating the gains of the past thirty years in Central Europe by strengthening the pillars of common values, security, and economics, and finding ways to advance these gains to the countries in Europe’s east. The United States and Central Europeans should lead the effort to keep the door to the West open and help the most eager countries, such as Ukraine and Georgia, prepare for the time when it is possible to move through it. Addressing difficult issues—whether democracy and the rule of law or business problems—works better in the context of a broad agenda rooted in US and Central European core interests, including security.

The Trump administration deserves credit for “showing up,” starting with presidential and vice-presidential visits to Warsaw and Tallinn in July and August 2017, respectively, and recently with visits by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to Budapest and Bratislava, and visits by Baltic and Visegrad leaders to Washington. The administration deserves additional credit for addressing Polish (and, to varying degrees, broader Central European) security concerns by continuing rotational military deployments, and by holding discussions about increasing them. Finally, the Trump administration deserves credit for embracing the Three Seas Initiative and the need to design constructive and cooperative solutions for its implementation in coordination with the EU.

The United States must avoid instrumentalizing Central Europe. Nevertheless, the Trump administration has also sent mixed messages about its views of a united Europe, transatlantic solidarity, Russia policy, and even democratic values. Western Europeans have periodically accused the United States of using Central Europe as a lever (or “Trojan Horse”) against Europe as a whole. This is generally false, but the Trump administration’s habit of anti-EU rhetoric has brought back this skepticism. The United States should not use its political capital or exploit its historic role to enlist Central Europe in an anti-EU agenda. The United States cannot offer Central Europe the benefits of EU membership (freedom of travel, a single market, EU funds), so pushing Central Europeans to choose between the United States and the European Union would be strategically divisive and politically damaging; the United States should not ask Central Europeans to act against their own interests.

Central Europeans can now step up. For much of the twentieth century, Central Europe saw itself, with reason, as an object and victim. For the first generation after 1989, Central Europe was preoccupied with the basics of reform and securing a place for itself inside a united Europe and transatlantic community. Central Europeans saw the United States as their champion. Having achieved so much, and no longer poor and beleaguered, Central Europeans should assume greater responsibility for working with the United States, and within Europe as a whole, to help set and execute a US-Central European agenda and a common US-European agenda.

Both the United States and Central Europe should remember their best traditions. Americans and Central Europeans face major challenges from without. Success lies in recalling how the West, with Central Europe and the United States in the lead, succeeded in the Cold War: by understanding that their national interests and shared values were ultimately indivisible. Now, as then, the way ahead lies in recalling their best traditions and avoiding their worst. The Central Europeans must avoid retreat to transactional parochialism, such as flirtation with “neutrality” (while accepting the benefits of the European Union and NATO) and short-term nationalist indulgence. The United States must avoid a retreat to nationalist isolationism and cynical spheres-of-influence deal-making. National patriotism, it is important to remember, is at its most compelling when rooted in universal values. The old slogan of nineteenth-century Polish freedom fighters is still apt: “We fight,” the cry went, “for your freedom and ours.”