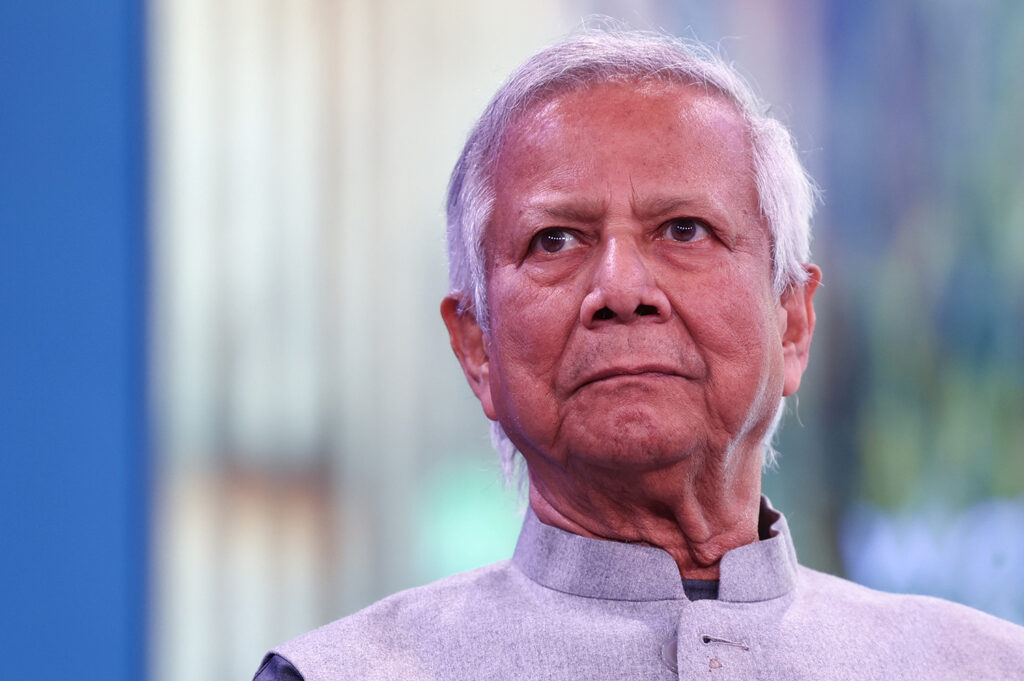

When Muhammad Yunus, chief adviser of the Bangladeshi interim government, stepped off his plane and onto a red carpet in Beijing in March, he did not just break tradition: He lit a fuse in South Asia.

Typically, new Bangladeshi leaders head to India for their first bilateral visit abroad, but Yunus instead traveled to China. Peking University bestowed him with an honorary doctorate. China’s ambassador in Dhaka hailed the trip as the “most important visit” by any Bangladeshi leader in the last half a century. Yunus himself declared that the Bangladesh-China relationship has entered “a new stage.” The symbolism was unmistakable: Dhaka is abandoning its decades-long balancing act between India and China for a more assertive embrace of Beijing.

Bangladesh, with which India shares its longest international border, is critical to India’s security. For China, Bangladesh is a vital partner in its Belt and Road Initiative and String of Pearls ambitions, offering a strategic foothold in India’s backyard. Welcoming Chinese influence may put wind in Bangladesh’s economic sails, but it comes with the risk of transforming the nation into a battleground for the Sino-Indian rivalry. Bangladesh, in its hasty geopolitical gambit, may have just traded a delicate tightrope for treacherous quicksand.

China’s gains and India’s losses

China didn’t hold back during Yunus’s visit. Bangladesh secured $2.1 billion in investments, loans, and grants. The real wins for Beijing, however, were strategic: a $400 million modernization deal for Mongla Port—Bangladesh’s second-largest seaport—and increased engagement with the Teesta River Comprehensive Management and Restoration Project.

The Teesta project, in particular, strikes at the heart of regional tensions. For over a decade, negotiations between India and Bangladesh over sharing the river’s water have stalled, with Bangladesh wanting a larger share to address water scarcity in the north. The Teesta Barrage, built to direct the flow of the Teesta River, sits perilously close to India’s “Chicken’s Neck”—the narrow corridor linking India’s mainland to its turbulent northeastern states, known as the Seven Sisters. This narrow corridor lies just a few hundred miles south of an area where China’s military presence is growing, positioning the strip as a strategic chokepoint. India perceives Chinese military presence in the region as an existential threat, as Chinese boots on the ground could quickly divide India in two.

For years, China has expressed its interest in the Teesta River management project due to the river’s strategic significance. Just last year, then Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina indicated that she would cede the project to India, given both nations’ shared stake in the river’s water, or perhaps a calculated measure aimed at soothing New Delhi’s security concerns regarding Chinese influence in the region. Yunus’s decision to greenlight China’s involvement constitutes a major shift, representing a diplomatic coup for China and a direct challenge to India.

Compounding this tension, some media outlets reported a possible Chinese proposal to construct an airfield in Bangladesh’s Lalmonirhat district, which is also near India’s “Chicken’s Neck” region. Soon afterward, media outlets also reported that India has bolstered its military presence in the area.

Bangladeshi diplomatic moves toward China didn’t stop there. For the first time, Dhaka explicitly opposed Taiwan’s independence. And the two countries brokered a deal to invite Chinese investment to modernize and expand facilities at the Mongla Port, which hands China another strategic foothold in the Bay of Bengal.

Yunus appears to see China as a springboard to elevate Bangladesh’s global stature. He even mused that Bangladesh could serve as “an extension of the Chinese economy” and the sole oceanic gateway for India’s Seven Sisters states, calling the states “landlocked”—a remark that surely rattled New Delhi.

This pivot toward China marks a stark departure from Hasina’s cautious ambiguity in balancing China and India during her fifteen-year tenure. Over the last decade of Hasina’s administration, China has become Bangladesh’s largest trading partner, top supplier of military hardware (including two submarines and support for a naval dock), and leading development partner under the Belt and Road Initiative. Yet, Hasina ensured that economic cooperation with China never undermined Dhaka’s relationship with New Delhi—especially given that her political party, the Awami League, has long been India’s ally.

Since Hasina’s dramatic exit amid the July 2024 uprising, India-Bangladesh relations have plummeted to their lowest ebb. Tensions along the border have flared. Just before taking power, Yunus issued a warning that any Indian attempt to destabilize Bangladesh could spill over to India’s volatile Seven Sisters states—a statement many Indian analysts interpreted as a veiled threat. Last year, Dhaka accused India of opening water gates to flood Bangladesh. India, in turn, raised alarms over attacks on minorities in Bangladesh—claims Dhaka dismissed as grossly exaggerated. In addition, the spread of disinformation among Indian media has added to these tensions.

On top of that, Hasina, now exiled in India, remains a festering sore in bilateral ties. Bangladesh has demanded her extradition to face charges related to mass killings and forced disappearances during student-led uprisings in July and August 2024, but India has so far refused. The Indian Army chief has publicly stated that normalized relations between the two nations hinge on Bangladesh installing an elected government—a pointed jab at Yunus’s unelected interim regime.

Eight months into his tenure, Yunus finally secured face time with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in April after New Delhi rebuffed Dhaka’s earlier overtures before the pivotal Chinese visit in March. Yunus brought up long-standing issues such as border killings and Hasina’s extradition, while Modi reiterated concerns about minority oppression in Bangladesh and cautioned against provocative rhetoric—likely referencing Yunus’s recent comments about India’s Seven Sisters region. Although a necessary first step toward repairing relations, the talks more closely resembled a recitation of grievances than an attempt at reconciliation. The ice finally cracked—but hardly melted.

Why Bangladesh must move with caution

Bangladesh has outgrown its days as a small power. As one of South Asia’s largest economies—and with a strategic position at the Bay of Bengal and a population of 170 million—Bangladesh now wields considerable political clout. With that clout, Bangladesh can more easily chart an independent foreign policy.

As the global order continues to evolve, great powers are realigning, and nations across Asia (including Bangladesh) are recalibrating their relationships to match new realities and national interests. Yet, this moment of opportunity demands caution. A headlong rush toward China risks Bangladesh’s future for four critical reasons.

First, China’s allure comes with caveats. Though Bangladesh has benefited from Chinese investment, there are still risks. Since 2014, China has pledged forty billion dollars to Bangladesh through its Belt and Road Initiative, yet only $7.07 billion has materialized. Although now operational, ventures such as the Padma Bridge and Payra Power Plant faced delays and cost overruns during construction. Furthermore, Chinese loans come with a 3 percent interest rate, higher than the rates offered by other lenders, though Beijing is now considering lowering the rate. Yunus’s government must continue to pursue careful loans and avoid the common risks associated with an overreliance on Chinese investments to secure Bangladesh’s economic future.

Second, India, a geopolitical heavyweight next door, cannot be ignored. Bangladesh sits nearly encircled by India, leaving both countries mutually dependent. Any friction with India over strategic projects like Teesta would trigger cascading security and economic consequences. Bangladesh’s ties with China must be fostered with careful geopolitical calculation, not as an impulsive reaction to the friction with India that has appeared since Hasina’s ouster. Strategic clarity, not emotion, should guide Dhaka’s choices.

Third, the United States looms as Bangladesh’s “third neighbor,” meaning that Dhaka’s shift toward China may have consequences beyond South Asia. As Bangladesh’s largest export market, the United States wields outsized influence over Dhaka’s policy. In Hasina’s final years, Washington ramped up pressure over Bangladesh’s closeness to China and democratic backsliding. Hasina was able to juggle US demands and maintain bilateral ties with the United States by leveraging her connections with India. Indian officials were concerned about the opposition in Bangladesh gaining power and lobbied their US counterparts to temper their criticism of Hasina’s administration. Yunus’s interim government lacks that buffer. The interim government is courting the United States—seeking energy deals, rolling out Starlink, and implementing changes to secure lower tariffs on US goods—hoping that the Trump administration will prioritize trade over geopolitical considerations and will see Bangladesh on its own terms, not as India’s junior partner. Yet the United States announced a 37 percent tariff on all imports from Bangladesh—though that has been temporarily reduced to 10 percent, alongside most of the world—which would be a significant economic hit. Amid the US-China trade war, Dhaka should at least aim to understand Washington’s evolving red lines before doubling down on closer ties to Beijing.

Lastly, a major foreign policy shift by the interim government, currently operating with a dissolved parliament, may trigger domestic unrest, policy inconsistency, and diplomatic friction. The interim government’s stated priority is to guide Bangladesh toward reform and elections. But the interim team may not have the democratic legitimacy that is needed to make a sweeping foreign policy change. Yunus’s pivot to China could commit Bangladesh to a course that the public may not support and the next elected government might not honor. Decisions of this magnitude—potentially redrawing Dhaka’s regional and global stance—would ideally require parliamentary backing, a democratic mandate, and political weight to handle the consequences. An interim regime, by its very nature, may be better suited to prioritize stability over implementing revolutionary shifts.

Bangladesh can continue to chase opportunistic gains with China, risking Indian ire and isolation (without a clear signal from its people that it has a mandate to do so), or it can recalibrate with restraint, preserving the equilibrium that has long underpinned its rise. Regardless of what choice it makes, Bangladesh must tread with caution. The paths it chooses will ripple across South Asia, determining whether Bangladesh emerges as a bridge between giants or a battleground where they clash. For a nation outgrowing its small-power past, the stakes have never been higher.

Wahiduzzaman Noor is a Bangladeshi national security professional and former diplomat at the Embassy of Bangladesh in Washington, DC, with expertise in South Asian affairs, Indo-Pacific Security, and counterterrorism.

Samantha Wong is a program assistant with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. Her work centers on the technology and security portfolio, where she researches and develops collaborative solutions to global challenges arising from China’s rise.

Further reading

Thu, May 15, 2025

How South Asia’s ‘swing states’ navigate India-Pakistan tensions

New Atlanticist By

Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives are quiet strategists in South Asia—but ignoring their roles risks destabilizing the region's fragile geopolitical balance.

Tue, Jan 28, 2025

After the Monsoon Revolution, Bangladesh’s economy and government need major reforms

Freedom and Prosperity Around the World By

In 2024, Bangladesh’s student-led “Monsoon Revolution” ousted an entrenched autocratic regime, marking a historic shift. Yet, with deep systemic corruption and political resistance, the road to stability remains uncertain.

Wed, Aug 7, 2024

Hasina is out. Yunus is in. Here are the three biggest factors to watch in Bangladesh.

New Atlanticist By Ali Riaz

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has fled Bangladesh, and Nobel Prize–winner Muhammad Yunus will lead an interim government. But several important questions remain unanswered.

Image: Muhammad Yunus, chief adviser of the government of Bangladesh, attends the annual World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland on January 23, 2025. Photo via REUTERS/Yves Herman.