Singapore must shift from state-led expansion to productivity-led growth

Bottom lines up front

- The “Singapore model” of a market economy under heavy government direction has led to strong headline numbers that obscure signs of significant stress.

- High land and housing costs, extreme inequality, and a very low fertility rate suggest that everyday life feels precarious for many in one of the world’s richest cities.

- Singapore needs a new playbook—otherwise the model may start to look more like a warning.

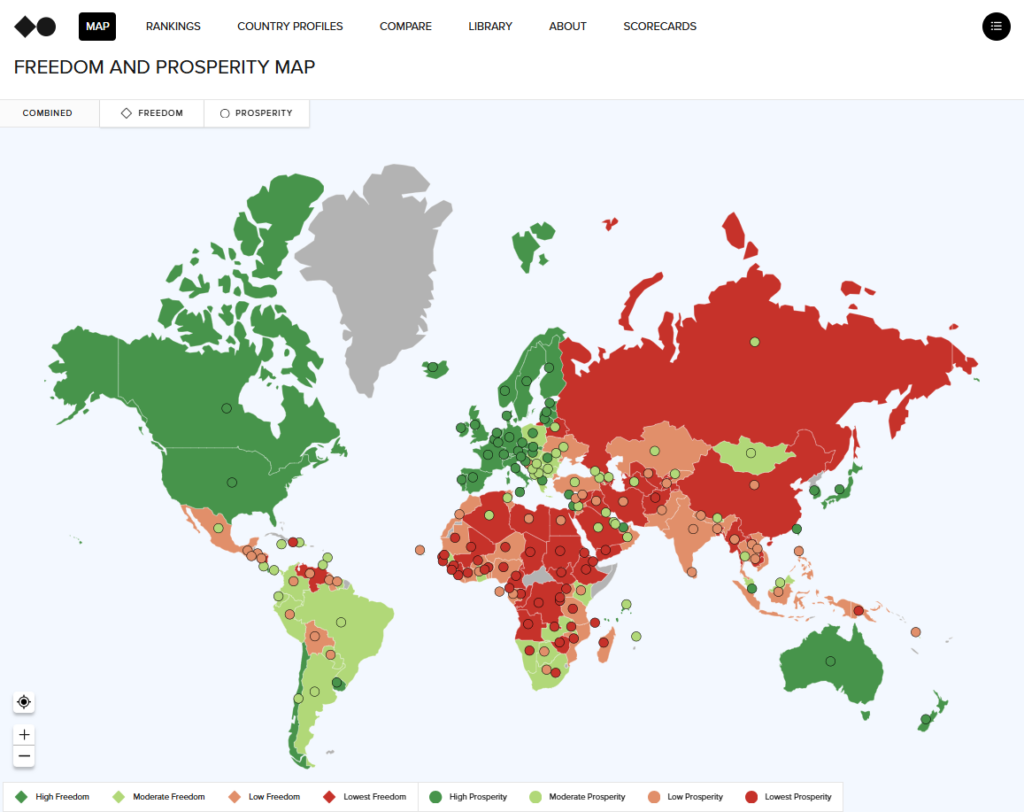

This is the fourth chapter in the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s 2026 Atlas. The Atlas analyzes the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

Evolution of freedom

Singapore’s post-independence development strategy was clear and, for a long time, well suited to the country’s advantages and constraints. A free port under British colonial rule since 1819, Singapore separated from Malaysia in 1965, which made continued outward orientation an existential necessity for the city-state’s survival. Developed-country trade liberalization encouraged offshore sourcing by multinationals, enabling Singapore’s government to build an export-oriented economy anchored in foreign direct investment. It prioritized manufacturing, later adding high-end services, and used targeted industrial policy to achieve its priorities. The strategy was reinforced by disciplined macroeconomic management, public investment in world-class infrastructure, and efficient public administration.

But what made the approach distinctive was not just openness to trade and investment—it was also the degree to which the state integrated regulatory, proprietorial, and allocative power. The government planned land use, owned most of the land base, channeled compulsory savings, and exercised strategic ownership through sovereign wealth funds and government-linked companies. This tight coupling of state and market produced order and speed and made full use of a global economic environment that favored openness. At the same time, however, it embedded government discretion at the center of daily life.

The economic engine was an extensive growth model, which expanded output by adding capital and labor to a fixed land base, rather than by sustained gains in total factor productivity. Singapore incentivized multinationals to produce in the country, scaled public investment, and—critically—liberalized foreign labor inflows to keep costs predictable. That choice made sense when the priority was to build a platform economy quickly. It is less convincing as a path to future prosperity. Heavy reliance on lower-wage foreign workers depresses incentives to automate, redesign jobs, and raise productivity. At the same time, large inflows of higher-skilled foreigners add to demand for scarce urban resources and amenities, especially housing, putting pressure on prices and widening social distance. Such social distance is seen where differences in income, opportunities, and daily living conditions deepen divides between groups. In such a system, the state can point to impressive aggregate outcomes while households at the lower end experience stagnant real wages and rising costs.

Households at the lower end experience stagnant real wages and rising costs.

Institutionally, Singapore has combined strong commercial rule of law and administrative capability with persistently narrow political competition. Elections are regular and cleanly administered, but contestation is constrained. The playing field is shaped by districting changes implemented shortly before each election; official campaign periods that last just nine days; and a long tradition of filing defamation actions against critics, including for statements made during the hustings. Mainstream media is not fully independent—there is substantive state ownership and oversight—and online speech is governed by broad statutes that give the executive sweeping, fast-acting powers. Passage of POFMA (Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act) in 2019 and FICA (Foreign Interference [Countermeasures] Act) in 2021 was justified by the government as defenses against misinformation and foreign interference, but the measures have also generated uncertainty about what is out of bounds. In practice, the fear and reality of punishment lead risk-averse citizens and institutions to overcomply. The effect is anticipatory discipline, more than visible coercion, engendering a climate in which people self-censor and where policy debate narrows.

The legal environment reinforces this equilibrium. Singapore courts are efficient, free from corruption, and commercially reliable—central reasons investors locate there. But the same state that regulates also owns land, large companies, and the largest pools of domestic savings. Political appointments, the use of civil defamation in political contexts, and the fusion of political and administrative authority create ambiguity for anyone engaged in contentious public speech or organizing. For most commercial actors, rules are clear and enforcement swift; for citizens considering robust political contestation, the boundaries are less legible and the costs potentially high. That asymmetry lowers the expected return on civic initiative and removes information the state needs for timely course correction.

The tight state-economy nexus is particularly visible in land, housing, savings, and capital allocation. Because the government owns nearly all the land and leases public housing on 99-year terms, “market prices” are necessarily shaped by policy. The Central Provident Fund (CPF) holds employees’ mandatory savings (currently amounting to 37 percent of employee compensation) and links a very large share of it to housing purchases and other government-defined uses. The sovereign wealth funds Temasek and GIC intermediate large public assets and maintain strategic holdings in major enterprises, while government-linked companies dominate substantial portions of the corporate landscape. This architecture has delivered order, speed, and scale. It has also raised economy-wide prices, encouraged rent extraction through asset inflation, and tilted returns toward capital and land rather than labor. When the state is everywhere—as de facto landlord, employer, investor, banker, business partner, regulator, customer, supplier, and even competitor in the provision of goods and services beyond public goods—experimentation by private enterprise narrows, not by prohibition but by crowding out, and by the rational impulse to align with official priorities, especially when reliant on the state for incentives or sales.

These facts sit awkwardly with conventional measures of “economic freedom,” such as those produced by the Fraser Institute or Heritage Foundation, which reward contract enforcement, low tariffs, and investment openness, have historically placed Singapore at top positions in their indexes. The economic pillar of the Freedom Index, mainly based on these same external sources, consequently ranks Singapore as the eighth most economically free country among the 164 nations covered. Those measures capture real policy strengths, but rankings such as these cannot capture how a directed ecosystem works on the ground when the state chooses where investment is most desired, sets the volume and terms of labor inflows, prices land it largely controls, and deploys large public capital to back favored sectors. Under such conditions, entrepreneurship is not forbidden, but it is less central to the model than in economies where the state is smaller and competition wider. A rules-based marketplace can coexist with discretionary steering from above. The visible results—macro stability, fast approvals, coordination in areas the state prioritizes—are valuable. But hidden costs—muted productivity incentives, lower household consumption, and limited diffusion of capability—accrue slowly and become apparent only when the external environment turns unfriendly.

Some might argue that Singapore’s example indicates that political freedom is unnecessary for economic development. After gaining independence, the government justified expanded restrictions on labor, media, and freedom of association as necessary to ensure political stability and attract foreign direct investment (FDI). But these restrictions remain in place even as South Korea and Taiwan, formerly authoritarian regimes, showed that political liberalization and a more participatory system could reinforce and enhance, not undermine, stability as economies mature (see Figure 1). In Singapore, constraints on expression—including in academia—reduce the diversity and depth of policy discussions. When dissent is costly and information selectively released, the system hears less from those who see problems first: low-wage workers, squeezed middle-class families, independent researchers, and small firms facing rising costs. This is not an abstract normative concern but rather a practical handicap in a complex, rapidly changing economy.

Figure 1. Political liberalization did not slow economic growth in South Korea or Taiwan

Gross domestic product per capita (purchasing power parity-adjusted, in 2021 constant international dollars) was obtained from the IMF data portal. The Political Rights component has been extended back to 1980 using V-Dem data and the same methodology as in the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes.

Evolution of prosperity

Singapore’s achievements on headline income are undeniable. Gross domestic product per capita has tripled since 1990, placing the country among the richest in the world. The Prosperity Index also records the country’s high levels of life expectancy and educational attainment. Singapore joined the world’s most developed countries several decades ago. These are the peers with which it should be compared, not its lower-income regional neighbors, particularly since the Singapore model of growth is clearly distinct from that of other high-income nations. An extensive growth model powered by factor accumulation leaves characteristic fingerprints. Singapore runs large current-account surpluses (over 20 percent of GDP annually since 2005) and builds fiscal buffers (persistent large budget surpluses); public investment is high; private consumption is low by advanced-economy standards; and productivity growth has been episodic outside a few frontier activities. This is the logic by which the system operates: Singapore prioritizes external competitiveness, recycles surpluses into foreign assets, and leans on a managed exchange-rate regime to hold down imported inflation and to maintain credibility. The main questions behind the numbers are how broadly they translate to all social strata and whether the current model is sustainable in the long run.

When dissent is costly and information selectively released, the system hears less from those who see problems first: low-wage workers, squeezed middle-class families, independent researchers, and small firms facing rising costs.

The inequality component of the Prosperity Index gives a visual answer to the first question. Compared to the Nordic European countries, Singapore has a much higher level of income inequality (see Figure 2). Other distributional measures, such as an estimated 0.7 Gini coefficient in terms of wealth inequality, point to the same conclusion. What’s more, these numbers most likely underestimate the actual level of inequality in Singapore. Most OECD countries include all legal immigrants (permanent and temporary residents) when estimating inequality, but Singapore excludes non-permanent immigrants, though they account for 39 percent of the labor force and are concentrated at the lower end of the income distribution. The country’s official measures of inequality (a 2024 Gini coefficient of 0.435 before and 0.364 after taxes and transfers) also exclude non-labor income, more than half the total. The real inequality gap in Singapore, compared with other developed countries, is probably much wider than estimated, while Singaporeans’ share of national income has almost certainly shrunk since 2014, the last time this number was released. Socioeconomic inequality is a direct product of the Singapore model, which generates costs borne by households through higher local-currency prices, crowding out of small and medium enterprises, thin wage growth at the base, and a muted share of national income going to labor and citizens.

Figure 2. Income inequality is higher in Singapore than in Scandinavian countries

Labor-market design is central to these outcomes. Liberal foreign-worker inflows have long been used to match demand cycles, contain wage pressures, and deliver what has been referred to as “labor peace.” Over time, this has reduced the incentive for employers to automate or redesign low-productivity work. A dual structure persists. At one end, a sizeable segment of the economy depends on low-paying, physically demanding and risky jobs that do not lead to productivity ladders for residents. At the other end, inflows of professionals and executives meet genuine skills needs but also fuel demand for scarce urban resources and amenities, especially housing, raising costs and intensifying competition for positional goods and elite educational tracks. The structure widens the gap between those at the lower and upper ends of the economy without building domestic capability commensurate with the country’s income level.

The real inequality gap in Singapore, compared with other developed countries, is probably much wider than estimated.

Housing and savings amplify the distributional effects. Singapore links a very large share of forced savings to Housing and Development Board (HDB) purchases on 99-year leases, with 76 percent of the population (down from 85 percent) housed in these government-run properties. When home values rise, owners enjoy wealth effects; when leases age and policy signals shift, uncertainty grows for households that cannot easily diversify. Land prices—set in a market the state effectively controls—ripple through business costs and wages. The expectation of continuing asset inflation encourages rent-seeking over entrepreneurship and leads families to shoulder significant leverage. A model that relies on rising asset prices to sustain consumption in a city of high living costs is one that exposes households to policy-driven valuation risk. It also depresses fertility (the 0.97 total fertility rate is among the world’s lowest) by increasing the cost of raising children in an expensive, dense, competitive urban environment.

Singapore’s 37 percent labor share of national income has been low relative to its peers, while gross operating surplus and property-related incomes loom large, at 54 percent. Government-linked firms and multinationals dominate many input and output markets, crowding out smaller domestic enterprises. Private consumption’s share of GDP (36 percent in 2024, down from 49 percent in 2001) is strikingly low for an advanced economy. These features set Singapore apart from the most prosperous and inclusive societies, where thicker wage floors, broader diffusion of capability, and less reliance on asset inflation anchor the social contract.

Education and health present a complex picture. Attainment is high and standardized test scores in math and science rank among the world’s best. But in a relentlessly competitive school system, there are concerns that heavy reliance on private tuition (70 percent of students) contributes to unequal educational outcomes and diminished social mobility by giving an advantage to those whose families can afford the extra expenditure. Additionally, translating education into broad-based opportunity is uneven since the economic structure does not generate enough high-productivity, middle-income jobs for residents outside elite tracks. Without stronger productivity growth at the firm level—driven by job redesign, automation, and diffusion of best practice—credentials do not guarantee commensurate wages. On the health front, a technocratic system achieves strong population outcomes (in terms of average life expectancy) at relatively low public cost, but it deliberately shifts financial risk to households through compulsory savings and copayments. In a city with high living costs and thin wage growth at the base, that risk burden is felt keenly even when headline indicators look strong.

Externalities are increasingly salient. Sustaining growth through population increases and construction intensifies congestion and environmental stress in a tropical, high-density city increasingly beset by climate change (high temperatures, frequent floods, rising sea level). Industry clusters that anchor the export platform—energy-intensive manufacturing, petrochemicals, aviation-related services, data centers—carry emissions and transition risks that will be costlier to manage as climate policy tightens globally. Meanwhile, the shift to attracting family offices and private wealth poses reputational and security risks—from money-laundering and accusations of “Singapore-washing” (intermediating funds through Singapore to disguise their origin or destination) to international criminal syndicates and scammers who use Singapore as a hub for their illicit activities. The result of this shift is to concentrate purchasing power in neighborhoods and assets where residents already feel priced out, with only modest spillovers to domestic capability building and financial-market depth.

When the cost of dissent is high and data releases are selective, independent journalists, researchers, and civic groups struggle to map distributional outcomes in real time. That deprives policymakers of useful feedback, early warnings, and good ideas from outside the official complex. It also erodes trust. Citizens are more likely to accept difficult adjustments when they believe the system listens to their concerns and shares risk fairly. Today, too much downside is borne by households, which face rising prices and policy-shaped asset risks while being told that government largesse through periodic non-entitlement transfers will cushion the blow. Such discretionary transfers—conditional, temporary, inadequate, and uncertain—are inferior to market wages that rise with productivity and distort political preferences by making the citizenry beholden to the governing party.

The path forward

Singapore will not succeed in the next decade by doing more of what worked in the last half-century. The world has changed. Globalization is retrenching, the international tolerance for mercantilist policies is narrowing, and great-power rivalry is intensifying with increased willingness to use economic pressure to exact political concessions. Regional competitors—from China to Vietnam and Indonesia—combine improving infrastructure and skills with labor costs Singapore cannot match. Subsidy races in major economies are reshaping value chains and contesting investment decisions with tools Singapore cannot or should not emulate at scale. The uncertain impact of technological disruption by artificial intelligence makes investment decisions difficult and complicates long-term planning. In this environment, doubling down on a model optimized for inflows of foreign labor and capital will yield diminishing returns and increasing vulnerabilities, while wasting scarce resources.

The first imperative is to move decisively from extensive to intensive growth. That means closely linking firm survival to productivity improvement. A credible path would temper reliance on lower-wage foreign labor in ways that raise the payoff from automation, process innovation, and job redesign—especially in service sectors where productivity lags and resident employment is concentrated. It will close some firms and raise costs for others in the short run, but without this shift, wages at the base will remain thin and inequality will worsen, no matter how many transfers the government can deploy. Complementary reforms should ensure that inflows of higher-skilled foreigners are aligned with building domestic capability rather than simply satisfying short-term demand and bidding up urban resource costs.

The political-legal setting must evolve in tandem with the economy.

Second, the scale and use of surpluses and reserves should be revisited, especially as the sovereign wealth funds which invest reserves have underperformed. A stronger exchange rate and slower reserve accumulation would lower imported inflation and relieve cost-of-living pressures. A larger share of fiscal resources can be redirected from broad corporate inducements and opaque industrial bets toward social spending that reduces household risk without dulling work and investment incentives. None of this implies fiscal profligacy or acting imprudently. It reflects a recognition that the opportunity cost of very large buffers, in a rich and aging society, includes foregone domestic investment in human capital, diffusion of capability, and life-cycle security.

Third, land and housing policy must be reoriented to lower systemic costs and reduce dependence on asset inflation. More retirement savings should be decoupled from housing, the long-term treatment of aging leases clarified, and the state’s control of land used to dampen, not amplify, economy-wide price pressures. Greater transparency around land pricing and HDB cost structures would improve trust and policy effectiveness, and enable better planning of investment decisions by households and businesses. Lower land costs would cascade through wages and prices, reduce the attraction of rent-seeking, and shift capital toward productive enterprise. It would also promote family formation by lowering the cost and uncertainty associated with housing, childcare, and eldercare.

Fourth, the growth playbook should move from picking winners at scale to catalyzing broad-based experimentation by private actors. Singapore has spent heavily, over decades, on research parks and sectoral “bets” that delivered mixed results. In a world where value is increasingly created in ideas, services, and intangibles, the priority should be to lower entry barriers, democratize access to data and infrastructure, and crowd in private risk-taking outside state-linked incumbents. Public capital can be powerful when it is allocated with discipline: to back competitive markets, not sustained rents; to fund diffusion of capability, not trophy projects; and to hold itself accountable to transparent criteria and sunset clauses.

Fifth, the political-legal setting must evolve in tandem with the economy. Removing the conflation of government and ruling party interest with the public interest, strengthening checks and balances on the executive’s exercise of powers, normalizing robust debate, and making distributional data routinely available would lower the implicit tax on civic initiative and improve policy through better feedback. Complex societies govern better when they listen widely and when the rules are clear and contestable—as evidenced by other Asian countries that have shown that political liberalization can coexist with order and strengthen legitimacy. Confidence in performance should reduce, not increase, the state’s reliance on ambiguity and speed in controlling speech and association.

Building institutions that allow competition in markets and ideas and that trust and empower ordinary citizens … is the surest way to keep Singapore exceptional.

Geopolitics adds urgency. Singapore cannot count indefinitely on frictionless access to foreign capital, technology, and markets. Practices once tolerated may be penalized. If the country continues to rely primarily on incentive-led FDI and imported labor in a city with high costs and rising environmental constraints, it will confront sharper trade-offs: either slower growth with rising inequality and social tension, or continued growth with greater external exposure and domestic fragility. Neither is an optimal strategy for the future.

The better alternative is a new “social compact” that matches the high-income status Singapore has achieved. It would place productivity and diffusion of capability at the center of economic strategy; align immigration and industrial policy with those goals; share risk more fairly with households; and widen the channels through which citizens can speak, organize, and help solve problems. It would move society from discretionary benevolence toward institutionalized confidence that rules are predictable and fair. It would sustain high income without leaning on ever-rising asset prices, grow wages at the base faster than the cost of essentials, and ease the pressures that make everyday life feel precarious to many in one of the world’s richest cities.

Singapore possesses the administrative capacity, fiscal resources, and human talent to make this transition. The PAP government, which has ruled for 66 years, faces no short- or even medium-term threat to its overwhelming hegemony. It recognizes the external and domestic challenges the economy faces, expresses concern about social mobility and social cohesion amid a “foreign-local divide,” and is attempting to “listen more” (albeit through channels and processes it controls). The government has even acknowledged that the model that got the country to where it is today is not the model that will take it further, because the world will not arrange itself to suit the old playbook. What it has not done is change the playbook. Instead, it is ratcheting up growth acceleration by placing bigger bets on “industries of the future” while holding on to established ones as a hub for “leading global firms.” Recognizing that “not everything will succeed,” the government argues that “if just one or two do, they can transform our economy and carry Singapore to the next level.” It is not moving toward political and intellectual liberalization, insisting instead that maintaining “social harmony”—given economic openness, racial and religious diversity, divisive social media and geopolitical tensions—requires holding fast to the tight rules of the past.

If Singapore changes its playbook, its freedom profile will become less lopsided—still strong on commercial rule of law and execution but balanced by more open contestation and clearer legal protections for speech. Its prosperity will be more inclusive and sustainable. Without the change, the headline numbers may stay impressive for a while, but the trade-offs will sharpen, and the miracle will appear less as a model to emulate and more as a cautionary warning. In the long run, a city-state’s greatest asset is the capability and confidence of its people. Building institutions that allow competition in markets and ideas and that trust and empower ordinary citizens, rather than domestic and foreign elites, is the surest way to keep Singapore exceptional.

about the author

Linda Y.C. Lim, professor emerita of corporate strategy and international business at the Stephen M. Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, has studied the Singapore economy for 50 years, and published other research on international trade and investment, women in the labor force, and overseas Chinese business in Southeast Asia. She co-edits AcademiaSG, an academic blog promoting scholarship “of/for/by Singapore.”

Explore the data

The Indexes rank 164 countries around the world. Use our site to explore thirty years of data, compare countries and regions, and examine the subindexes and indicators that comprise our Indexes.

Stay Updated

Get the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s latest reports, research, and events.

Stay connected

Read all editions

2026 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Against a global backdrop of uncertainty, fragmentation, and shifting priorities, we invited leading economists and scholars to dive deep into the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries around the world. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

2025 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists, scholars, and diplomats analyze the state of freedom and prosperity in eighteen countries around the world, looking back not only on a consequential year but across twenty-nine years of data on markets, rights, and the rule of law.

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: Tourists visit shops and street food vendors near Chinatown MRT station in Singapore in 2019. Source: Shutterstock

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media