At the end of 2025, the White House released a comprehensive National Security Strategy (NSS) that reflects the strategic worldview of US President Donald Trump’s current administration. Like the 2017 NSS issued during Trump’s first term, this new document is branded as “America First,” but it goes further in its clarity, prioritization, and ideological framing. The 2017 NSS already emphasized border security, economic nationalism, sovereign decision-making, and a renewed focus on great-power competition, yet the newly issued NSS formalizes these instincts more sharply. It treats sovereignty, industrial revival, the end of mass migration, tight border control, and burden-shifting to regional partners as core national objectives rather than rhetorical elements of diplomacy. The subsequently released National Defense Strategy (NDS) reinforces this hierarchy by translating these political priorities into concrete force-planning choices, especially around Iran, Israel, and the role of Gulf partners as frontline regional security providers.

At the same time, Trump’s current NSS is more explicit than its 2017 predecessor in delineating a hierarchy of regions and interests. Whereas earlier versions still treated the Middle East as a central theater of policy execution, the new strategy bluntly states that not all regions matter equally at all times—and that the Western Hemisphere and the Indo-Pacific should receive the lion’s share of strategic attention. The NSS also reinforces the notion that economic security, energy dominance, and revival of the defense industrial base are fundamental to national security, not peripheral to it. Although the NSS is a statutory planning document and therefore binding on departments for implementation, Trump’s foreign policy style has always been adaptive, personalized, and operationally flexible. Thus, the NSS should be treated as a reliable directional guide, one that shapes expectations, alliances, budgeting, and bureaucratic activity, while leaving room for Trump’s preference for personal diplomacy and transactional deal-making where needed.

It is in this context that the Middle East—and particularly the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)—emerges not as a downgraded region, but as a strategically redefined one: less central to day-to-day US force planning, yet still pivotal to the administration’s concepts of burden-sharing, deterrence, and regional stabilization.

The Middle East: Enduring interest, but no longer central

Among the most striking elements of the new NSS is its recalibration of the Middle East’s place in US foreign policy. For decades, the region consumed disproportionate diplomatic attention, military deployments, and crisis-management resources because it supplied vital energy, served as a Cold War battleground, and generated conflicts with global spillover potential. Today, those foundations have weakened: the United States is a net energy exporter with greater resilience to supply shocks, and great-power competition now plays out far more in the Indo-Pacific and in technological and economic domains than through Middle Eastern proxy wars.

However, the fact that the Middle East no longer dominates US strategic planning does not imply disengagement or irrelevance. The NSS is careful to define the Middle East as a region of enduring interests that must not be relegated to instability or hostile domination. The United States retains core objectives: preventing any adversarial power from controlling Gulf hydrocarbons or the chokepoints through which they transit, ensuring freedom of navigation of waterways such as the Red Sea and the Strait of Hormuz, countering terrorism and radical movements, supporting Israel’s security, and expanding the normalization dynamic of the Abraham Accords.

The regional focus is therefore shifting from militarized management toward political stabilization, strategic deterrence, investment collaborations, and cost-efficient conflict management. The NSS frames the Middle East increasingly as a zone of partnership, innovation, and capital exchange rather than as the site of long, resource-intensive wars. The NDS adds an important nuance: while confirming that the Middle East is no longer the central theater for US force planning, it explicitly commits to retaining the capability for “focused, decisive action” in the region, illustrated by operations such as Midnight Hammer against Iran’s nuclear infrastructure and Rough Rider against the Houthis, while expecting regional actors to manage most of the security workload between such interventions.

Burden-shifting: The GCC as regional security providers

One of the clearest implications for GCC states is the NSS’s burden-shifting logic. Washington does not intend to underwrite regional security in the same way it once did. Instead, the White House expects capable regional actors, particularly Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and to a lesser extent Qatar, to assume leadership in securing maritime routes, deterring hostile adventurism, stabilizing proximate conflict zones, and countering terrorist networks. The United States will remain a strategic backstop, especially at the high end of military power, but the NSS encourages a division of labor where Washington leverages diplomatic influence, advanced deterrent capabilities, and intelligence, while expecting Gulf capitals to provide financial, logistical, and regional operational support. The NDS makes this division of labor more explicit by directing the Department of Defense to “empower regional allies and partners to take primary responsibility for deterring and defending against Iran and its proxies,” while the United States concentrates on high-end enablers, surge operations, and global priorities such as homeland defense and the Indo-Pacific.

This is not a sudden change, but rather a deeper institutionalization of trends that have been emerging for a decade. The GCC has long demonstrated an increased appetite for autonomous security roles, whether through counter-piracy patrols, Yemen interventions, Red Sea stabilization efforts, or investments in Central African and Horn of Africa equilibria. Trump’s NSS validates these ambitions and situates them within a US strategic architecture, rather than treating them as ad hoc regional experiments. For Gulf capitals, this recognition is beneficial: their regional activism is not only tolerated, it is encouraged as a core element of maintaining regional stability in lieu of direct US military domination.

From conflict theater to economic and technological platform

Another significant shift in the NSS narrative is the re-casting of the Middle East as an economic, technological, and financial platform, rather than a theater for perpetual conflict. The NSS recognizes that regional leaders have embraced diversification, industrial development, and sovereign wealth strategies that expand beyond hydrocarbons. It also emphasizes US opportunities in nuclear energy, artificial intelligence (AI), defense industrial cooperation, logistics networks, and supply chain localization. The Middle East is treated as an increasingly strategic geography for future economic corridors, especially those linking Africa, South Asia, and the Mediterranean.

This framing aligns neatly with GCC trajectories. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar have long sought to position themselves as global logistics hubs, aviation nodes, sovereign wealth investors, and technology accelerators. With the NSS emphasizing US economic security, energy dominance, and domestic manufacturing revival, Gulf states can leverage bilateral partnerships to show how investment projects, whether in nuclear energy, AI, aerospace, or critical minerals, support American jobs, reindustrialization needs, and technological gains. If packaged correctly, a Gulf-US economic deal now has political value in Washington that goes far beyond foreign direct investment: it can be framed as contributing to domestic industrial revival and strategic supply chain safety. The NDS reinforces this economic-security linkage by treating arms sales and defense industrial cooperation with GCC states as part of a broader effort to “supercharge” the US defense industrial base, making Gulf procurement and potential co-production not only a regional stabilizer but also a mechanism for sustaining US military capacity.

From deterrence to decisive operations: The NSS–NDS approach to Iran

The NSS conveys a strong view that Iran’s disruptive influence has weakened due to Israeli military pressure and to targeted US actions designed to degrade Iran’s nuclear potential. However, the situation has shifted dramatically in recent weeks. Widespread protests across Iran, triggered by deep socioeconomic grievances and political repression, have created an atmosphere of internal volatility not fully captured in the NSS released in late 2025. The Trump administration has responded with forceful rhetoric, warning Tehran that further repression or attempted regional escalation could trigger additional US military strikes. These warnings, coupled with reports that Washington is actively considering another limited, targeted strike on Iranian military infrastructure, have generated both reassurance and unease in GCC capitals. Here, the NDS adds two revealing elements: first, it publicly frames Operation Midnight Hammer as having “obliterated” Iran’s nuclear program and weakened the regime and its Axis of Resistance. Second, it explicitly states that Gulf partners and Israel are now expected to carry primary responsibility for containing Iran’s conventional and proxy capabilities, with the United States stepping in episodically when decisive force is required.

The ongoing instability in Iran introduces a new variable into the regional equation. While the NSS presents Iran as strategically weakened, current developments demonstrate that internal unrest can make the regime simultaneously vulnerable and unpredictable. The possibility of US kinetic action raises concerns about Iranian retaliation across the Gulf, whether through drones, cyberattacks, missile strikes, or activation of regional proxies. GCC leaders therefore view current tensions through a dual lens: understanding that US pressure aligns with long-standing Gulf concerns about Iran’s nuclear ambitions, yet also wary of the escalation risks that accompany any US–Iran confrontation.

The NSS balances deterrence with an emphasis on pursuing peace deals and post-conflict stabilization, including in Gaza and Syria. Trump’s political style is highly confident about presidential diplomacy and conflict resolution, and the NSS treats mediation as a strategic tool to bring difficult bilateral environments into a more stable architecture. This dynamic underscores that while the NSS prioritizes stability and “realignment through peace,” the Trump administration remains fully prepared to use force when it believes core US and allied interests are threatened, a stance entirely consistent with the NSS’s emphasis on “peace through strength.”

Although this is broadly reassuring for the GCC, residual anxiety remains. If Washington chooses to secure regional stability through big-ticket diplomatic bargains, especially where Russia or Israel are involved, Gulf capitals will expect assurances that their security will not be traded for conflict de-escalation. However, many Gulf leaders now possess significant diplomatic capacity and mediation credibility of their own. The NSS creates an opening for GCC states to position themselves as mediators or stabilizers rather than as passive recipients of US decisions. The Gulf’s growing diplomatic centrality, from Gaza cease-fire talks to Sudan, Libya, or the Horn of Africa, fits well with an NSS that prefers localized responsibility and regional realignment rather than direct US intervention. Still, the current crisis underscores a critical reality: any US–Iran confrontation, even a limited one, will have immediate consequences for Gulf security, energy markets, and maritime stability, reinforcing the importance of GCC preparedness, joint air and missile defense integration, and sustained coordination with Washington as the situation continues to evolve. In this sense, the NDS largely confirms the NSS’s direction of travel but narrows the margin for ambiguity: it signals that future Iran-related crises will be handled through short, sharp US operations nested within a regional architecture in which the GCC and Israel shoulder greater routine responsibility.

Will GCC capitals be surprised or concerned?

Little in the NSS will shock senior decision-makers in the GCC. Most regional governments have already experienced Trump’s approach firsthand, benefitted from strong bilateral ties, and understand that Washington’s foreign policy has permanently moved away from nation-building, democracy promotion, and open-ended security commitments. The more consequential shift in recent weeks has been the intensification of US–Iran tensions, which has temporarily elevated the Gulf within Washington’s strategic focus despite the NSS’s assertion that the region is no longer central. GCC capitals now find themselves preparing for multiple scenarios, ranging from a calibrated US strike on Iran to potential Iranian retaliation, even as they recognize that none of this contradicts the NSS’s underlying logic of deterrence, burden-shifting, and threat-management rather than long-term occupation or nation-building.

Overall, the NSS is more likely to produce re-calibration than alarm. The strategy is consistent with Gulf countries’ expectations that they will be treated as indispensable pillars of regional stability and as partners in defense technology, energy investment, and maritime security. The NDS largely reinforces this assessment: it does not downgrade GCC importance, but instead clarifies the price of being central—greater spending, deeper integration with Israeli and US forces, and a willingness to absorb more day-to-day risk in managing Iran and regional crises.

How the NSS will guide GCC responses

The NSS will provide Gulf policymakers with an actionable framework for deepening relations with Washington. First, Gulf capitals can present themselves as regional security providers, offering maritime patrols, counter-terrorism support, Red Sea and Bab al-Mandab stabilization, and specialized capacity-building. Second, GCC countries can frame investment deals as US industrial wins, emphasizing how AI, aerospace, nuclear, and defense co-production create US jobs and secure American supply chains. Third, Gulf states can symbolically align with Washington on sovereignty narratives, emphasizing secure borders, state authority, and skepticism toward external ideological intervention, areas where their domestic priorities already converge.

Finally, GCC states will possibly manage their relationship with China more carefully, offering Washington assurances that high-sensitivity sectors will remain insulated from Chinese involvement while still leveraging Chinese trade and capital where appropriate. In doing so, Gulf leaders can demonstrate that multi-vectorism increases stability and economic growth without jeopardizing strategic trust.

A strategically manageable landscape

The Trump administration’s NSS is a sophisticated refinement of “America First.” It sets clear priorities, clarifies regional hierarchies, and emphasizes economic and technological competition as the foundation of power. For the GCC, the implications are significant, but manageable. Rather than being marginalized, Gulf partners are now expected to assume greater security responsibility, serve as stabilizers, and act as premium platforms for bilateral economic and technological exchange. The NSS ultimately positions GCC countries not as passive dependents of US security guarantees, but as mature strategic actors capable of shaping their region while deepening mutually beneficial ties to Washington.

Read together with the NDS, the picture becomes sharper: the GCC is central to a burden-sharing model in which the Middle East is no longer the main theater of US strategy, but remains a crucial test case for how America First can combine limited, decisive US force with empowered regional allies to deliver “peace through strength” without returning to the era of open-ended wars.

Kristian Alexander is a senior fellow and lead researcher at the Rabdan Security & Defense Institute (RSDI) in Abu Dhabi.

Further reading

Wed, Jan 21, 2026

Why US markets are betting on Saudi Arabia

MENASource By Khalid Azim

Saudi Arabia’s long-term strategy is coherent, ambitious, and increasingly credible. US debt capital markets, for now, appear to agree.

Tue, Dec 16, 2025

What will 2026 bring for the Middle East and North Africa?

MENASource By

As 2025 comes to a close, our senior analysts unpack the most prominent trends and topics they are tracking for the new year.

Tue, Nov 18, 2025

The Trump-MBS meeting comes at a pivotal moment for Vision 2030

MENASource By Frank Talbot

Saudi Arabia is looking to attract more international investors, keep supply chains running, and maintain a consistent stream of visitors.

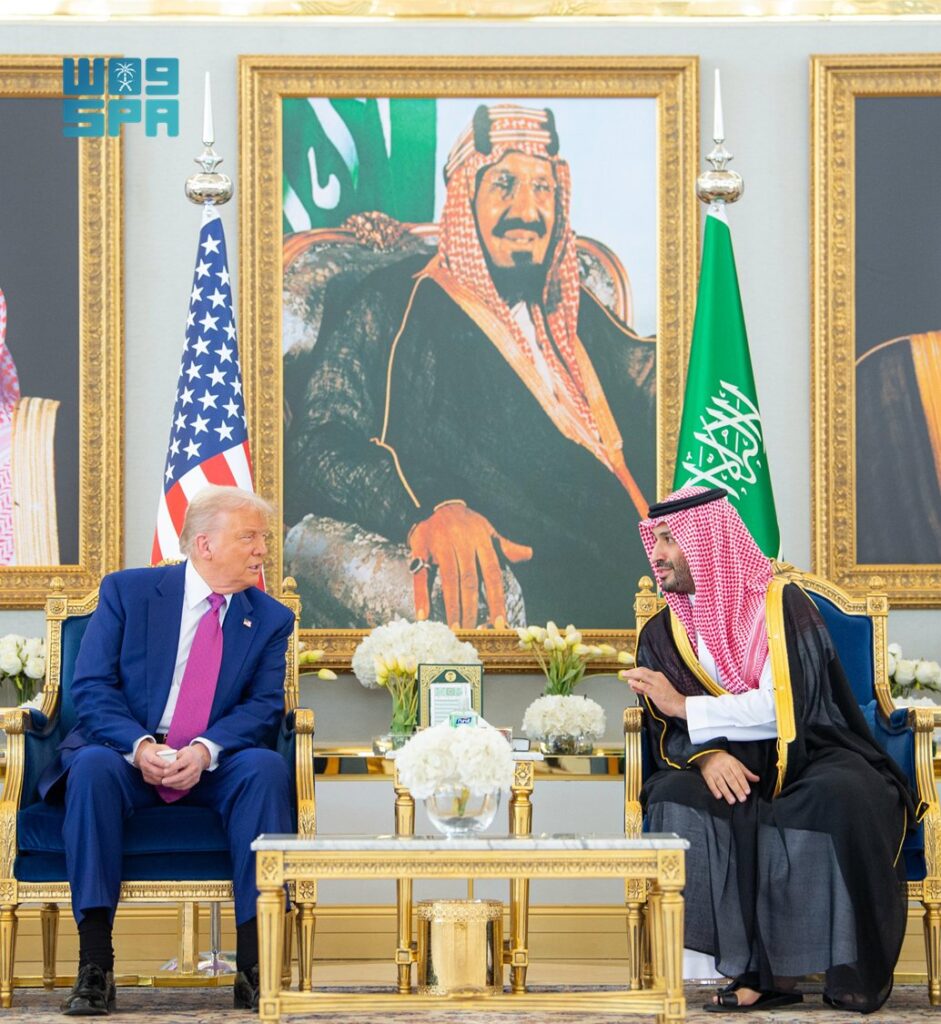

Image: U.S President Donald Trump arrives in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on Tuesday May 13, 2025 and is greeted by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, kicking off a four-day swing through the Gulf region. Trump has also said he may travel on Thursday to Turkey for potential face-to-face talks between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on Russia's war in Ukraine. (Saudi Press Agency handout via EYEPRESS)