Coronavirus comes to Sudan

As the COVID-19 virus rips through the developed world, less well-off countries are beginning to prepare for the worst within a strained resource environment. In this respect, Sudan is no different from dozens of other African countries. But the stakes somehow feel higher.

Not yet one year into a historic political transition and in the midst of an economic collapse, Sudan’s future was already hanging in the balance. The addition of a national and global public health crisis now has the potential for a ‘make or break’ impact on the country. If the government doesn’t respond effectively, the pandemic could call into question the case for long-term civilian rule and the prospects for economic stabilization—which may in turn undermine the international community’s commitment to backing the revolution.

Taking action

Sudan’s transitional government should be applauded for many of its early efforts to deploy its limited resources wisely. Recognizing the potentially devastating health and economic effects of the virus, the government has focused on educating the public on prevention and mitigation efforts—demonstrating once again just how much has changed for the better in a post-Bashir Sudan.

A high-level ministerial committee was stood up early on to coordinate efforts, and it declared a nationwide health emergency weeks ago, on March 16. Co-chaired by the ministers of health, information, and interior (the last of which is a military appointee), the committee has helped bridge many of the operational divides that Sudan’s transitional constitution created between civilian and military leaders. The group moved early to close Sudan’s land borders with Egypt, when an early cluster of cases emerged there, and started requiring health checks and quarantines at the Port Sudan sea border as many Sudanese started returning from Gulf countries earlier this month. The restriction on air travel to and from highly-infected countries has now turned into a global travel ban with all of Sudan’s airports closed to international traffic.

At home, the government is taking social distancing seriously, making every possible effort to limit the kinds of large social gatherings that, ironically, had become the symbol of the Sudanese people’s strength and resilience as they took to the streets for ten months last year in pursuit of “Freedom, Peace, and Justice.” In the past two weeks, a nationwide curfew has been imposed from 8pm to 6am every day; a prohibition on large-scale political, social, cultural, and sports gatherings is in effect; schools and universities have once again been shuttered for the remainder of the academic year; and this week, even Sudan’s prisons were emptied of more than four thousand non-violent offenders to reduce overcrowding and blunt the spread of the disease there. The government is now also said to be considering a two-week shelter in place requirement, following South Africa’s lead, which would see the social and economic life of the country ground to a halt.

With a level of transparency rare for the country, Sudan’s civilian health minister is now holding daily press conferences to update the country on best practices for prevention and to highlight the ever-expanding list of government efforts to fight the disease. The ministry has further teamed with the country’s mobile phone operators to push out daily reminders of best practices for social distancing.

But will it be enough? Sudan currently reports only five confirmed cases nationwide, with one fatality. All are being attributed to Sudanese returning home from abroad and carrying the infection with them. However, given the almost total lack of testing and near-absent health care system, that figure is most assuredly grossly underestimated. Last week alone, more than three hundred Sudanese suspected by health officials as having the virus escaped from government-administered quarantine facilities, while one hundred Sudanese nationals returning from Egypt were reportedly able to evade health screenings at the border.

From prevention to response

Despite the government’s worthwhile prevention efforts, when the virus takes hold—and all indications are that it will—Sudan is in perhaps one of the worst situations anywhere in the world to mobilize an effective national response. The same conditions that plague many other parts of Africa, and that will make the disease so difficult to prevent from spreading there, also haunt Sudan, namely: grinding poverty, lack of household savings to offset lost income, and lack of access to clean water, proper sanitation, and health supplies. And while it may not have the teeming urban slums of mega-cities like Nairobi or Lagos, Sudan still has millions living in displaced persons camps across Darfur and the Two Areas where COVID-19 could rip through with devastating effect.

A collapsed health care system hollowed out by thirty years of corrupt rule has also left the country with as many as only eighty ventilators and two hundred intensive care hospital beds. Even government-run containment facilities lack the ability to care for the sick for the necessary fourteen-day quarantines. Perhaps most disturbing is a growing popular sentiment that Sudan’s high daily temperature and young population will stave off the worst effects of the disease, causing many young people to feel impervious to the malady—a not uncommon response globally, but a potentially devasting one in a country like Sudan where many generations live under one roof.

Beyond the basics of a functioning health care system or the compliance of a willing public, Sudan lacks the economic resilience required to withstand the near-term effects of the pandemic. The country is already suffering from a balance of payments crisis, an exchange rate crisis, and a massive debt and arrears burden that has seen the country unable to pay for basic commodities like wheat in recent weeks. Simply put, Sudan has virtually no fiscal or monetary policy tools left to deploy to cushion the inevitable blow that will come from a further loss of productivity, revenue earnings, and foreign exchange.

Adding to Sudan’s economic burden, the national-level economic conference intended to enlist broad-based public support for the government’s economic reform agenda (namely, the cutting of subsidies for commodities like fuel and wheat), has been postponed from this past week and has not been rescheduled. And an international donor conference intended to bring in fresh pledges of international financial support still lacks a host and also appears destined to be pushed back from its hoped-for June date.

More broadly, as both Arab Gulf and Western governments turn their political attention to domestic response efforts, they are likely at the same time to revisit development budgets in the face of their own economies and societies being ravaged by the disease. In the face of this pull-back, profoundly aid-dependent countries like Sudan have to reconcile themselves to the likelihood that even pledged assistance funds might not materialize this year, and a go-it-alone approach may have to be contemplated.

Political costs

While the likely prospect of simultaneous health and economic crises should incite serious soul searching in Sudan, perhaps most worrying of all are the potential political and social costs that these dual crises could exact on the country. After all, Sudan, in the midst of an extraordinary political transition period, lacks a unitary command structure, and the transitional arrangement requires the civilian authorities and military to share power and duties in ways that are not always clear under Sudan’s transitional constitution. Thus far, in the prevention phase of the pandemic, that coordination has seemingly gone well, with military forces acting in line with civil authorities to close borders and limit public gatherings to enforce social distancing.

But will that coordination continue as the crisis deepens? Some in Sudan’s international “Friends Group” are already quietly identifying a timid response from the prime minister himself, who they have never credited with forceful or decisive leadership, as a potential concern. At a time of national crisis, fears are real that the military, as the country’s only functioning national institution, will step forward in ways that make civilian authorities look weak or feckless, and just at the moment when civilian rule should be becoming more entrenched, not less.

Going forward, all eyes will be assessing Prime Minister Hamdok’s ability to reassure a worried public, the skeptical donor community, and an unreformed security sector that he can rally a national response to the crises the country faces. If any of those audiences loses faith in his, or the civilian cabinet’s, ability to take decisive action to lead the country through the crisis without reverting to military rule, Sudan’s transition risks stalling out and reverting to the old power centers that held sway in the country for the past three decades.

Cameron Hudson is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. Previously he served as the chief of staff to the special envoy for Sudan and as director for African Affairs on the National Security Council in the George W. Bush administration. Follow him on Twitter @_hudsonc.

Questions? Tweet them to our experts @ACAfricaCenter.

For more content, go to our Coronavirus: Africa page.

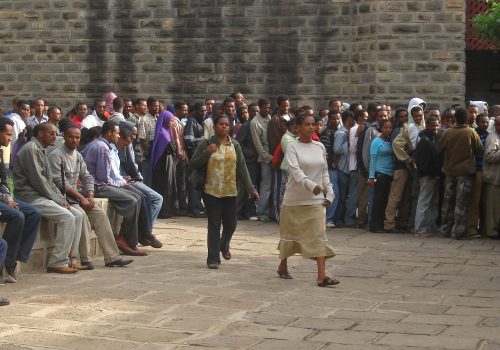

Image: A view of Khartoum, Sudan. (Flickr/Christopher Michel)