Coronavirus deals a blow to Ethiopia’s elections

On March 31, the government of Ethiopia indefinitely postponed historic elections that were scheduled to take place in August.

The postponement of these elections is noteworthy for many reasons. To start, Ethiopia is the first African nation in what is likely to be a wave of countries—including Burundi, Malawi, Tanzania, and possibly Côte d’Ivoire—that will be forced to set back highly contentious political contests in response to the novel coronavirus pandemic, with significant implications for the outcome.

Ethiopians have been waiting for the August elections with bated breath, as they were expected to produce the first competitive polls since election results in 2005 were violently overturned by Ethiopia’s ruling party (a minority-led cabal that had held power since 1991, and was finally overthrown in February 2018 after years of national uprising). Much hinges on the outcome of these first elections since Ethiopia’s popular revolt: the winning party or coalition will set the terms of a national reconciliation process, oversee the drafting of a new constitution, and further the privatization of Ethiopia’s industries. The new leadership will also determine the fate of Ethiopia’s controversial system of ethnic federalism—which was ostensibly designed to protect the autonomy of Ethiopia’s many different “nationalities,” but has been in practice a system of ethnic segregation and the means through which the few have ruled the many. The next election is also expected to serve as a critically-important referendum on the ethnic federalist system, with voters choosing between “nationalist” parties that have been organized on ethnic lines and want to preserve the federalist structure, and a new set of pan-Ethiopian parties (including Prime Minister Abiy’s Prosperity Party and Berhanu Nega’s Ethiopia Citizens for Social Justice) that promote a unitary social system.

Since the fall of the old order, the security situation in much of Ethiopia, especially in the southern Oromia region, has markedly deteriorated. Inter-ethnic competition has surged, as communities attempt both to settle old scores and to seek new power within the emerging political order. Even before the elections were postponed due to coronavirus, it was unclear whether they would take place without significant violence accompanying the polls. For that reason, some Ethiopians may well be breathing a sigh of relief over the delay. Indeed, most of the opposition groups—including the National Movement of Amhara (NaMA) and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), both leading rivals to Abiy’s party—were quick to signal their support. This is not only because they recognize that campaign rallies, voter registration, and other electoral processes would speed the spread of the virus; many opposition leaders had already feared that the timeline to elections was too short to produce a level playing field.

If anything, the postponement of elections is likely to undermine Dr. Abiy’s odds of retaining his office. Like the American president Donald Trump, he will be forced to confront elections in the midst of whatever suffering and economic wreckage the pandemic has caused, and he will be judged on his administration’s response. How successful will he be in facing down this pandemic?

On the plus side, Ethiopia is one of the better-developed nations in Africa. It has for decades been a top recipient of foreign aid; in consequence, it has disciplined security services that can be mobilized to assist the pandemic response, and it boasts a relatively well-developed health system. Though only major cities have hospitals staffed by full-time doctors, there are health centers and clinics distributed throughout the country (though far fewer than needed in rural areas). These clinics will not be able to provide respirators or intensive care to those worst-afflicted by the coronavirus, but they should be capable of performing diagnostic tests and distributing medicines and vital health information on preventing the spread of COVID-19. Ethiopia will also benefit from a mature cadre of politicians who can be relied upon to put public health above their personal political ambitions—Abiy’s decision to postpone the election, and the opposition’s embrace of that move, are both proof of that. Abiy’s international star power, though often regarded as a mixed blessing at home, may also prove to be a vital asset during this crisis, if it enables him to drum up more support from the G20 for Ethiopia and other African nations. Africa faces a critical shortage of personal protective gear, respirators, and other vital medical supplies, and the only place to get them is abroad; so Abiy’s stature in the international community may make the difference between life and death for many.

On the downside, Abiy’s administration has a poor track record of managing humanitarian crises. One of Abiy’s earliest stumbles was his inadequate response to a displacement crisis in the early months of 2019, when more than two million Ethiopians were driven from their homes by ethnic conflict and the general breakdown in law and order that accompanied the dismantling of the old, iron-fisted security apparatus. Abiy was widely panned for ignoring the plight of those internally displaced persons.

Abiy’s administration has likewise come under criticism for what many consider a belated response to the threat of the coronavirus. To be fair, Ethiopia was quick to adopt protocols for dealing with coronavirus: it quickly adopted airport screening measures, it was one of the first African countries to obtain the capacity to test for COVID-19 (Ethiopia started testing on February 7, long before the United States brought testing online), and it had established a hundred-bed quarantine facility and 24-hour information hotline by mid-February. Ethiopia also closed its schools and prohibited large gatherings at about the same time New York and Washington, DC did, in mid-March. (A good timeline of Ethiopia’s prevention measures can be found here.) Authorities in Addis Ababa have also provided handwashing stations across the city.

Ethiopia did not, however, join the vast majority of other nations—both in Africa and across the West—in banning flights to and from mainland China as the coronavirus began to spread across the world. The decision to keep operating the flights was based partially on sheer economic necessity—even with the continued flights to China, CEO Tewolde Gebremariam claims that the airline has sustained losses of $190 million due to the coronavirus travel slowdown. (Tewolde also recently pointed out that the ongoing flights permitted Chinese billionaire Jack Ma to make a $3.6 million contribution of needed medical supplies, including one hundred thousand N95 masks, to Ethiopia.) But the decision to continue flights to mainland China also hinted at Beijing’s outsized influence in Addis Ababa and sparked outrage across the continent—given Ethiopia’s role as a transit and economic hub, it was reasonably feared that Addis Ababa could turn into a vector for spreading the virus across East Africa and beyond. Abiy’s government later came under fire for continuing flights to Europe, even as Italy and Spain became new epicenters for the coronavirus. It was not until late March (on the 20th and 29th) that Ethiopian Airlines suspended flights to 110 countries affected by coronavirus, including Italy, Spain, and parts of China. (It continues to fly to Beijing—the list of suspended flights is here.) At the time of the flight suspensions, Ethiopia had recorded twenty-six cases of COVID-19; all of them originated abroad, but none of the infected individuals, surprisingly—very surprisingly—was reported to have traveled in China.

As he attempts to delay the onset of the coronavirus epidemic in Ethiopia, Prime Minister Abiy is walking a tightrope. His country has been on the verge of breakdown since the national uprisings two years ago, and the coronavirus crisis is likely to prove deeply destabilizing. Pandemics breed death, poverty, suffering, and paranoia everywhere, and Ethiopia will be no exception. Dr. Abiy has already been lambasted, even in the immediate wake of winning the Nobel Prize, for his extended shut-downs of the Internet, and for his harsh crackdowns on rebels in his native Oromia region. Jawar Mohammed, an influential Oromo political rival, has already claimed that the Internet shutdown has dangerously limited access to information about COVID-19. Those who suspect Dr. Abiy of authoritarian tendencies are likely to be alarmed—justly or otherwise—by the restrictive measures required to combat COVID-19. As in the United States, tribal tensions will be inflamed by the perception that some districts have better access to federal resources than others. And the heated atmosphere of misinformation in Ethiopia’s social media space is also likely to be a serious impediment to stability and to the health response.

Perhaps most worryingly, the novel coronavirus is poised to strike Ethiopia at a time when the nation’s political survival rests on the government’s ability to enlarge and redistribute the country’s economic pie. Under the old regime, the vast majority of Ethiopians felt starved of economic opportunity. New revenue is desperately needed to employ and appease the many millions of youths who feel that their futures have been short-changed by the previous regime, and who have the power to re-take the streets at any moment. No political transition will succeed without their consent, and their consent depends upon having more to eat than they had before. So a crippling global recession could not have hit Ethiopia at a more deadly time.

The specter of a collapsing Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa is almost as frightening a prospect as the novel coronavirus itself—and Abiy’s economic trade-offs, including his questionable decision to continue flights to China amidst the spreading pandemic, need to be viewed in that light.

Bronwyn Bruton is the director of programs and studies of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. Follow her on Twitter @BronwynBruton.

Questions? Tweet them to our experts @ACAfricaCenter.

For more content, go to our Coronavirus: Africa page.

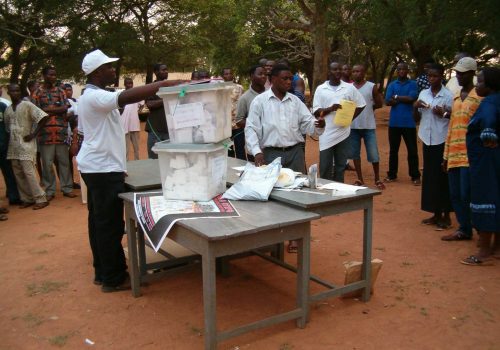

Image: A voting queue in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia during the 2010 polls. (Flickr/BBC World Service)