This week Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu became the first sitting Israeli head of government to travel to Africa since Yitzhak Rabin went to see Morocco’s King Hassan II in 1993. Netanyahu made stops in Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, and Ethiopia; while in Uganda, he also met with leaders from South Sudan, Tanzania, and Zambia. Although much of the media coverage of the trip has focused on the ceremony at Entebbe, where Netanyahu unveiled a modest monument commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the daring rescue by Israeli commandos of hijacked airline passengers—a raid commanded by the prime minister’s older brother Yonatan, who lost his life during the mission—the real story is the significant return of Israel in recent years to a continent that had been virtually closed to it for a long time.

This week Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu became the first sitting Israeli head of government to travel to Africa since Yitzhak Rabin went to see Morocco’s King Hassan II in 1993. Netanyahu made stops in Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, and Ethiopia; while in Uganda, he also met with leaders from South Sudan, Tanzania, and Zambia. Although much of the media coverage of the trip has focused on the ceremony at Entebbe, where Netanyahu unveiled a modest monument commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the daring rescue by Israeli commandos of hijacked airline passengers—a raid commanded by the prime minister’s older brother Yonatan, who lost his life during the mission—the real story is the significant return of Israel in recent years to a continent that had been virtually closed to it for a long time.

In the 1960s, when many African states achieved independence, Israel was one of the first countries to establish diplomatic relations with them and to offer them assistance. Israeli ambassadors operated in thirty-three countries and the country was, for a period, a major aid donor. As longtime Foreign Minister (and later Prime Minister) Golda Meir acknowledged in her memoirs: “Did we go into Africa because we wanted votes at the United Nations? Yes, of course that was one of our motives—and a perfectly honorable one—which I never, at any time, concealed either from myself or from the Africans. But it was far from being the most important motive, though it certainly wasn’t trivial. The main reason for our African ‘adventure’ was that we had something we wanted to pass on to nations that were even younger and less experienced than ourselves.”

However, following the Israeli victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, seven African countries severed their ties with the Jewish State; twenty-three more broke off relations after the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the Israeli occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, territory belonging to Egypt, a member of the Organization of African Unity. Subsequently, among African states, only Malawi, Lesotho, and Swaziland kept full diplomatic relations with Israel. In November 1975, the nadir in Israeli-African relations came when nineteen African countries voted in favor of the infamous United Nations General Assembly resolution identifying Zionism with racism, although the measure’s sponsors failed to achieve an African consensus when five African countries—Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Malawi, Swaziland, and the Central African Republic—voted against the draft and sixteen other African countries abstained.

Following the 1978 Camp David Accords, which brought peace with Egypt, Israel has slowly reestablished or established ties with nearly all Sub-Saharan African countries, the exceptions currently being Djibouti, Comoros, Guinea, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad, Somalia, and Sudan (although Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud and several of his ministers recently met with Netanyahu in a visit to Tel Aviv that was not reported until this week, and delegations from Mali and Niger have also come calling).

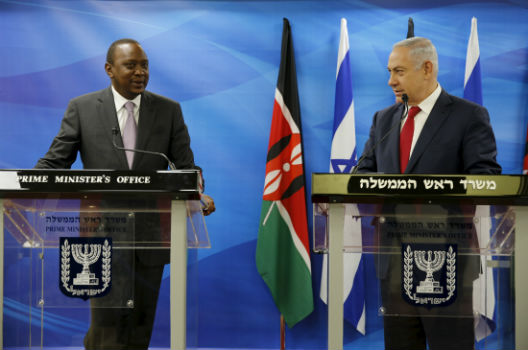

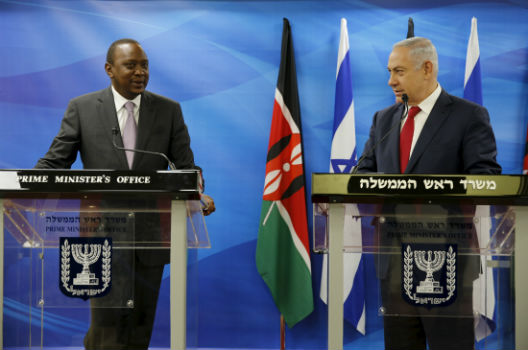

Setting off on his visit to East Africa, Netanyahu told his cabinet that “Israel intends to return to Africa” because the diplomatic links have “has very important implications vis-à-vis varying our international alliances and international relations, which are expanding to the major powers in Asia, to Russia, to Latin America and—of course—to the African continent.” One of the goals of the five-day trip was to rally support for restoring Israel’s observer status at the African Union, which was revoked in 2002 at the behest of the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. The proposal that garnered support from several of Netanyahu’s hosts, including Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta who described it as “not just good for Kenya,” but also “good for Africa” and “good for global peace.” The Kenyan leader cited the common interest that his country and its neighbors had with Israel in combatting Islamist terrorism. In fact, Israel will be helping Kenya build a 440-mile wall along its border with Somalia to prevent al-Shabaab and other militants from crossing that frontier. Kenyatta also announced an agreement between the two countries to share intelligence.

On a similar vein, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn of Ethiopia not only promised to work to upgrade Israel’s position at the African Union, declared that “the East African corridor has the huge potential for cooperation with Israel, and we need to engage Israel,” adding that those African countries which disagree with Israel on certain issues had no right to veto the rest of the continent’s cooperation with the Jewish State. The Ethiopian leader also publicly thanked Israel for its support in securing for Africa’s second most populous country a rotating seat on the UN Security Council beginning next year and promised to reciprocate by helping Israel in international forums.

In fact, although it has gone largely unremarked, better relations with African countries have contributed concretely to Israeli diplomatic successes like the failure in September 2015 of the proposed the International Atomic Energy Agency resolution that would have mandated inspections of Israeli nuclear facilities. Four African countries—Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, and Togo—voted against the measure, seventeen others abstained, eight were absent, and only seven Sub-Saharan African countries voted against Israel.

Beyond the political stakes, there are also increasing economic and commercial ties between Israel and its African partners, as underscored by the representatives of more than fifty Israeli firms who accompanied Netanyahu on the trip. In fact, in many cases, the investments made by Israeli business, especially in the water, agriculture, energy, and information technology sectors of several of Africa’s emerging economies helped pave the way for the renewal of diplomatic cooperation. In Rwanda, for example, an Israeli-American company, Gigawatt Global, is behind a year-old solar power plant that boosted the country’s generation capacity by 6 percent, providing efficient renewable energy to some 15,000 homes. The plant, East Africa’s first utility-scale photovoltaic facility, was a finalist for 2015 US Secretary of State’s Award for Corporate Excellence in the category of environmental sustainability.

Israeli official development agencies as well as private charities have also ramped up their activities in Africa. Since it was founded eight years ago, the Israeli nonprofit Innovation: Africa has used Israeli solar and water technologies to deliver clean water to nearly one million rural villagers in seven African countries (the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Malawi, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda). In 2012, a unique partnership was launched between the Ethiopian Ministry of Agriculture, the US Agency for International Development (USAID), and Israel’s Agency for International Cooperation (MASHAV) to promote economic growth in rural areas by strengthening smallholders’ production of fruits and vegetables with market potential; in May 2016, this tripartite development program, built on an earlier bilateral Israeli-Ethiopian initiative, was extended for another three years.

Following his meeting with Netanyahu, Rwandan President Paul Kagame, whose country has had, since 2014, a partnership agreement with Israel establishing a forum for regular consultations between the two countries and boosting investment, mentioned several areas which were ripe for future cooperation: “There are new areas as we go forward such as water management. Israel has a lot of capacity that not only Rwanda but the rest of Africa can benefit from. Israel manages scarcity of water resources better than anyone in this world… Israel has made huge advancements in areas of technology of agriculture that has multiplied the productivity better than you see anywhere else. We are very keen on tapping into this and other areas of capacity building such as areas of infrastructure, energy and other aspects.”

After wrapping up his week with an address to the Ethiopian parliament in which he invoked King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, Netanyahu tweeted, “Israel is coming back to Africa; Africa is coming back to Israel.” Whether the romance will be sustained this time remains to be seen, but what is certain is that an exciting new chapter in a very old story is being written.

J. Peter Pham is Director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. Follow the Africa Center on Twitter @ACAfricaCenter.

Image: Kenya's President Uhuru Kenyatta (L) stands next to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as they deliver joint statements in Jerusalem February 23, 2016. REUTERS/Amir Cohen