Mauritania’s presidential election on June 22 stands to mark the country’s first democratic transfer of power since independence in 1960. This comes as Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, who assumed control in a 2008 coup d’état, has agreed to step down, abiding by term limits. Aziz’s ruling Union for the Republic (UPR) party maintains a strong grip on power, but there have been signs of pushback since Aziz directed the abolition of the country’s senate in 2017. The opposition has returned to participate in the current election after largely boycotting in 2014, and the polls will serve as a test for the Muslim Brotherhood party, Tawassoul, which currently heads the opposition.

Mauritania is one of West Africa’s most resource-rich countries, and investment interest is on the rise. Development has started on its Greater Tortue Ahmeyim deep-water gas field, one of the region’s largest discoveries to date with an estimated fifteen trillion cubic feet of gas, and major mining companies continue to invest in the country’s substantial gold and iron ore deposits. Mauritania is also an important security partner in the Sahel, as a member of the US Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership and the G5 Sahel Joint Force. This article previews the country’s coming election, underscoring key trends and what to watch for.

Who are the major players?

Mohamed Ould Ghazouani is Aziz’s chosen successor and the UPR’s flagbearer. He is a military general, Aziz’s defense minister, and a longtime ally of the president. There are five other candidates, of whom three are significant. Sidi Mohamed Ould Boubacar, an independent candidate endorsed by Tawassoul, led the country’s transitional government between 2005 and 2007 and served as ambassador to the United Nations. Biram Dah Abeid is known for his activism against slavery, which remains a human rights issue in Mauritania. Finally, Mohamed Ould Maouloud is the leader of the opposition Union of the Forces of Progress (UFP) party.

What can we expect in terms of turnout?

Historically, turnout for Mauritania’s presidential elections has been around 55-65 percent, with legislative elections pulling in 70-75 percent of registered voters. This discrepancy, which runs counter to global trends, may suggest that Mauritanians feel closer affinity to local politicians or believe that presidential races are less competitive. Low turnout may also be a symptom of fatigue with Aziz and the UPR. Turnout will thus be an indicator of political mobilization and perceptions of openness.

How successful will the ruling party be under its new flagbearer?

The UPR will likely win with a large plurality. For reference, Aziz won in the first round in both 2009 and 2014 with 53 and 82 percent respectively (the opposition boycotted in 2014). However, studies show that a party’s incumbency advantage declines in an open election, so one might expect Ghazouani to fair slightly worse than Aziz. The 50 percent mark, which would preclude a runoff, will therefore be a useful measuring stick in the coming polls. Ghazouani’s vote share will inform the UPR’s popular mandate moving forward.

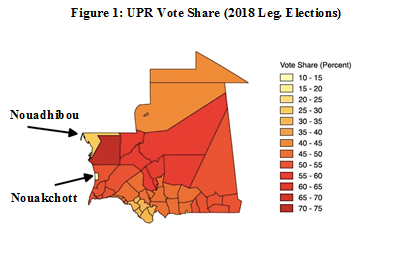

Regional voting patterns are also something to watch for. UPR support varies across the country, per Figure 1, with higher opposition support in the major cities and in the south of the country, where many Afro-Mauritanians feel disenfranchised.

What is the implication of null votes?

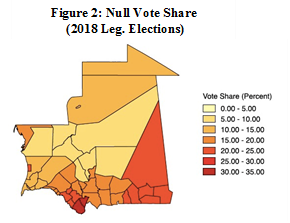

The last legislative polls produced over 185,000 null votes, or about 18 percent of total votes cast. Mapped in Figure 2, high null vote shares correspond to areas of lower UPR support, seen in Figure 1. Comparing vote totals from 2018’s municipal and legislative elections, there is evidence that the null votes may serve as protest votes against the UPR. As such, the ruling party’s support is substantial but overstated. Parliamentary aggregation procedures also favor the UPR, which won almost 60 percent of the seats with just about 40 percent of the vote.

How will the Islamists fair?

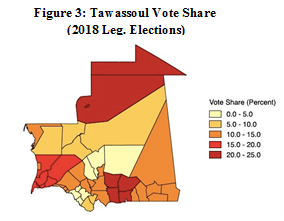

Tawassoul currently heads the opposition, having received between eleven and thirteen percent of the vote across the different lists in 2018. Tawassoul’s leader has repeatedly branded the party as moderate, yet the government denounces Tawassoul as radical and extremist, holding a strong anti-Islamist line, which has gained the favor of Saudi Arabia. Government pressure helps explain Tawassoul’s caution, endorsing Boubacar instead of putting forth its own candidate. The party has performed best at the municipal level in the past and only offered up its own presidential candidate in 2009, receiving 4.76 percent of the vote. The level of national mobilization for Boubacar will advise Tawassoul’s ability to scale up in the future.

What can campaigning tell us?

The campaign period is between June 7 and June 20, and the candidates are on parallel tracks to visit each of the country’s thirteen regions. Of note, Aziz spoke at the opening of Ghazouani’s campaign, and Ghazouani’s schedule indicates that his penultimate stop will be an extended visit to Aziz’s hometown. Clearly, the UPR is still counting on Aziz’s pull. While Ghazouani has had each region to himself on the campaign, Boubacar and Abeid overlapped on five of their first six days. In terms of rallying supporters, this clearly favors Ghazouani and speaks to the fragmented state of the opposition.

Can we expect a credible election?

Opposition warnings of an electoral “hold-up” perpetrated by the government likely foreshadow claims of fraud. No international observers have been permitted, and opposition candidate Biram Dah Abeid was imprisoned for five months in 2018. The opposition has garnered some concessions, though, and its mere participation is a positive signal after several boycotts. Notably, opposition appointees were added to the election commission in May, and the government agreed that the military would no longer vote on a separate day, increasing transparency. It will likely be difficult to find independent assessments of the election, meaning that opposition claims will have to be weighed against those of journalists, civil society, and any data released by the election commission.

Will there be protests or violence?

Prior elections have avoided violence, though protests against the abolition of the senate in 2017 were “actively dispersed.” If tension were to arise, cities and the southern regions would be the expected flashpoints.

Final Takeaways

Though the outcome may seem preset, the June 22 election will provide valuable insight into the state of Mauritanian politics. The UPR will be looking to maintain its authoritarian status quo despite a change in leadership, similar to the unfolding transitions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, and Zimbabwe. While the election is thus more a referendum on the UPR than a true opportunity for a pluralistic opening, the opposition’s vote share does matter. A stronger opposition showing would signal an erosion of UPR authority and could limit the range of options for the ruling party moving forward, with one such option rumored to be an Aziz comeback in 2024. Above all, the election will set the tone for the next five years, which will be critical in determining the extent of authoritarian entrenchment in Mauritania.

Luke Tyburski is a project assistant with the Africa Center.

Image: President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz has been the face of Mauritanian politics since 2008 but has agreed to step down. (Photo Credit: Flickr/Medou Mido)