Africa Embraces the Promise of Free Trade

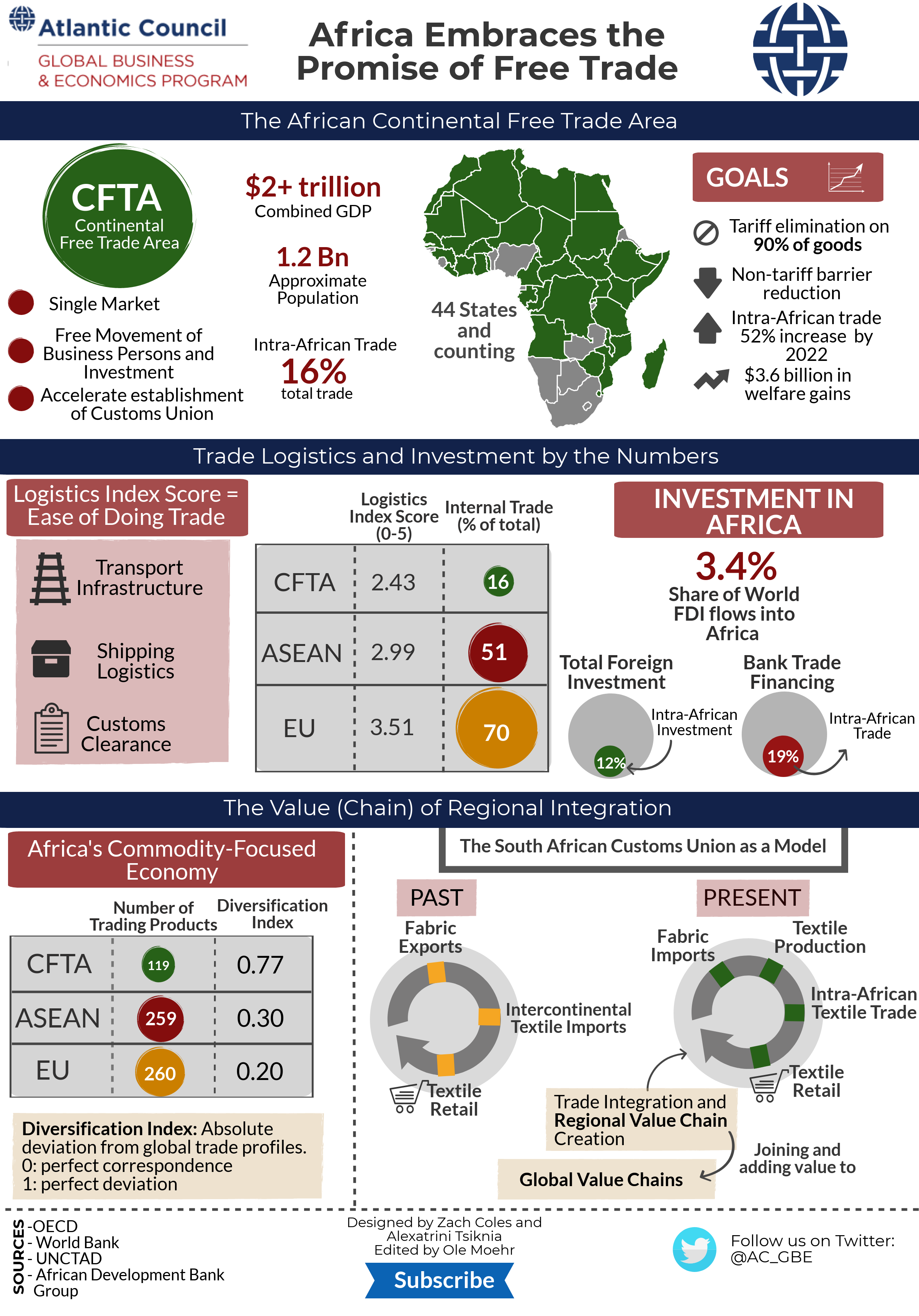

Overshadowed by news about tit-for-tat trade wars and rising protectionism, on March 21, forty-four African states signed an agreement to launch the African Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) at an African Union (AU) summit in Kigali, Rwanda. Eleven African countries, including the continent’s two largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, did not sign the agreement largely due to concerns of their respective domestic industries and labor organizations. The CFTA is a far-reaching free trade agreement that aims to not only eliminate most tariff barriers on goods and services, but also harmonize investment policies, intellectual property rights, rules of origin, and product standards. Ultimately, the CFTA’s goal is to create a continent-wide customs union that promotes Africa’s economic transformation. This edition of the EconoGraphic provides an overview of the CFTA’s scope, assesses the conditions for boosting intra-African trade, and outlines the importance of developing regional value chains to foster sustainable economic growth across Africa.

One of the CFTA’s key objectives is to significantly increase intra-African trade. The continent’s commodity-focused economies are currently sending 82 percent of their exports to non-African countries. To bolster intra-African trade, the CFTA member states will have to go beyond their commitment to eliminate tariffs on 90 percent of goods. Without addressing excessive non-tariff barriers, such as unduly bureaucratic customs processes and onerous sanitary and phytosanitary regulations, and improving the underdeveloped road and rail infrastructure, the CFTA will not reach its target of increasing intra-African trade by 52 percent by 2022 from its level in 2010. For instance, according to the World Bank, Congolese customs typically take almost a month to clear a container with automobile parts. In particular, exporters of perishable agri-food products suffer as a result of costly delays in the customs process. To make intra-African trade an engine for growth, it is vital to reduce non-tariff barriers and goods’ transport times across the continent. Nonetheless, the CFTA will be able to build upon positive momentum in intra-African trade. For one, manufactured goods now make up more than 50 percent of all intra-African exports. This underscores the growing industrialization in African economies. The CFTA is also expected to foster intra-African trade by better coordinating the “spaghetti bowl” of different trade facilitation regimes between the continent’s different Regional Economic Communities (REC). In addition, many of the CFTA’s forty-four signatories have already ratified the World Trade Organization’s Trade Facilitation Agreement, which aims to “expedite the movement, release and clearance of goods”.

Developing regional value chains (RVCs) is essential for fostering intra-African trade and transforming Africa’s economy. By leveraging existing competitive advantages of neighboring African countries, RVCs have the potential to reduce the continent’s dependence on commodity exports and diversify economic output. RVCs facilitate economies of scale and attract investment. This in turn promotes competition, more innovation, and finally higher productivity. To achieve the CFTA’s ultimate goal of changing Africa’s economic structure, African workers must climb-up the value chain “from lower to higher productivity sectors” to add more value to each product and service they produce or render. Manufacturing goods and agri-foods account for the majority of intra-African trade, which offers RVCs room to grow across the continent. Strong RVCs would help African regions and companies to not only take part in (i.e. export commodities), but more importantly contribute significant value to global value chains (GVCs). Meaningful participation in GVCs will bring cutting-edge knowledge and technology, and, in turn, higher productivity to African regions and companies. A more productive private sector will stimulate economic growth and increase household income. As explained above, the CFTA’s aim to reduce tariff and non-tariff barriers is vital to allow RVCs and GVCs to develop.

To make the CFTA a reality, the forty-four signatory countries must first follow through on their commitment to ratify the agreement. The Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA), set-up to combine three of the continent’s RECs, offers a cautionary tale. Launched with much fanfare in 2015, only two countries have ratified the TFTA thus far. Fifteen countries must ratify the CFTA for it to enter into force. Finally, to facilitate Africa’s economic transformation, the CFTA’s signatories must assuage fears in Nigeria and South Africa to convince the continent’s two largest economies to join the agreement.