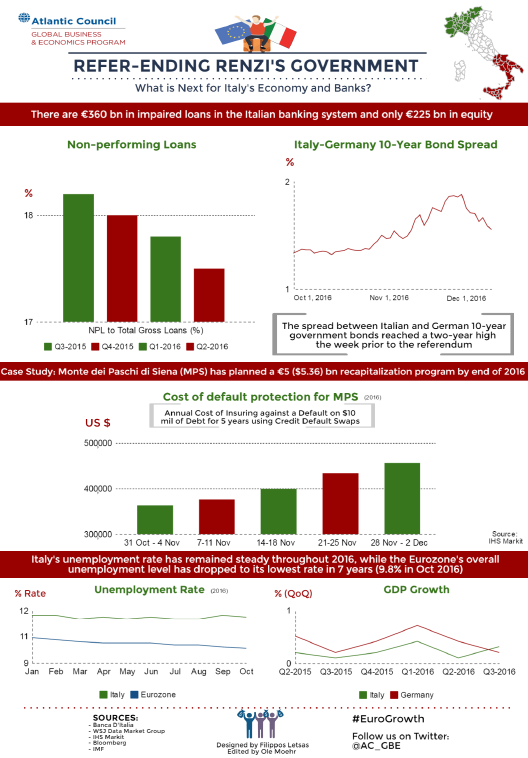

On December 4, Italian voters rejected former Prime Minister Renzi’s constitutional reform referendum. The result of the referendum renewed concerns about the economic recovery in Italy, stability of the Euro, broader European economic integration, and rising populism across Europe. In the week following the referendum, global markets have focused their attention on the ailing Italian banking sector. The Italian banking system is undergoing a serious restructuring in an effort to raise capital and increase profits. The €360 billion in non-performing loans (NPL) on Italian banks’ books – about one-third of the Eurozone’s total – underscore why shares of Italian banks have declined by ca. 50 percent since the beginning of 2016.

Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Italy’s oldest and third-largest bank, put forward a restructuring plan to raise €5 billion by the end of 2016 to reduce the percentage of NPLs on its balance sheet from 44 to 16 percent. However, the growing political uncertainty is contributing to investors’ increasing doubts whether Monte dei Paschi can raise the necessary capital despite having €20 billion in non-performing loans on its books. If Monte dei Paschi fails to raise €5 billion by the end of the year, the Italian government would likely be forced to bail it out. It remains unclear whether the European Union’s bail-in rules would affect Monte dei Paschi’s retail investors who hold €2 billion in subordinated bonds.

On Thursday, December 8, European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi calmed markets’ nerves by announcing that the ECB would continue its quantitative easing program until December 2017. The bond-buying scheme by the ECB supports Italian banks in their efforts to reduce their NPL ratio and boost profitability. The next day, however, Monte dei Paschi’s shares plummeted more than 10 percent after the ECB rejected its request to extend the recapitalization period past the December 31 deadline.

In our view, growth is at the core of Italy’s economic and banking problems. Without higher and more inclusive growth, future Italian governments will find it significantly harder to control the national debt – accounting for 133 percent of Italy’s GDP, reduce unemployment, and contain the spread of populism and anti-establishment sentiment. The next administration must continue Renzi’s reform efforts and push through further structural reforms to restore investors’ confidence and allow banks to access much-needed fresh capital.