Stalled growth in the UK, Germany, and Japan darken global economic outlook

In 1960 Harold Macmillan was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Konrad Adenauer was Chancellor of West Germany, and Nobusuke Kishi (Shinzo Abe’s grandfather) was Prime Minister of Japan. All three leaders visited Washington that spring just as a recession was starting in the United States.

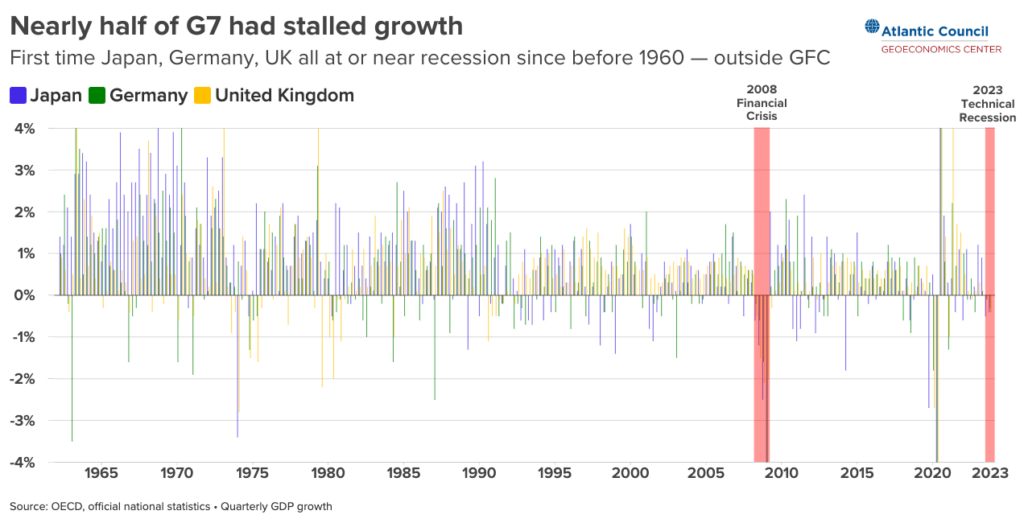

In the sixty-four years since, those three major economies have never all faced a recession at the same time (outside of the Global Financial Crisis). But as of last week all three were in technical recessions—until updated GDP numbers on Monday showed Japan very narrowly avoiding one.

What’s particularly concerning is that nearly half of the G7 experienced stalled growth at the end of 2023 and none of these slowdowns are alike. In Germany, the manufacturing sector is going through a painful transition as weak demand, competition on electric vehicles, and the aftershocks of Putin’s invasion have slowed growth to a standstill.

In the UK, the post-Brexit labor shortage and sluggish productivity growth have created an economic cycle that still hasn’t curbed high prices. In fact, the government has signaled that this recession might be the only way to break the back of inflation.

Then there’s the most interesting case, Japan, where an aging population is consuming less and less. In fact, Japan is on pace for a 15 percent contraction in its population between now and 2050. With an average age of forty-nine, Japan has one of the highest proportions of elderly citizens in the world. When the disappointing GDP data came out last month, Japan lost its spot as the third-largest economy in the world.

The good news is that each of these recessions is expected to be short-lived. The latest data out of Japan on Monday shows 0.4 percent GDP growth in Q4, (meaning it avoided two straight negative quarters of growth). Even before the new data, the Nikkei has been surging due to expectations that the Bank of Japan (BOJ) may finally be ending the era of negative interest rates. In the UK, Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey may finally be able to start cutting rates this summer. And in Germany, new manufacturing orders unexpectedly jumped 10 percent at the end of year—prompting hope that the spring will truly be a season of revival.

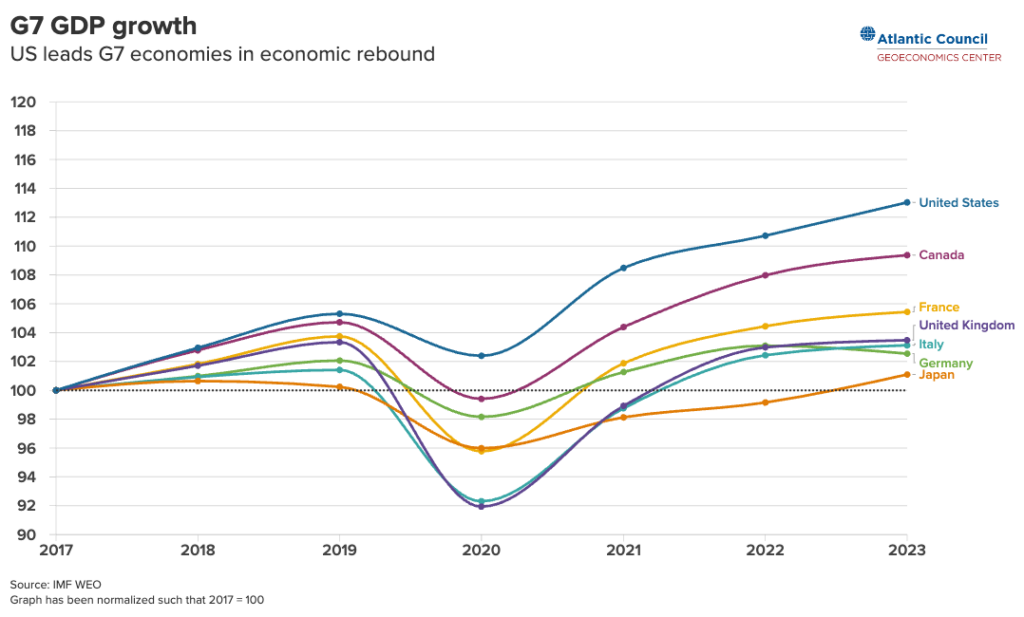

But here’s the key difference between now and then. When the United States turned the corner in 1961, the import demands from its booming middle class helped pull up countries around the world. But in 2023, the United States was already the fastest growing G7 country. In 2024, US GDP growth will likely slow, not surge.

Combine the US situation with China’s deepening economic problems and the picture becomes clear. The world’s two largest economies won’t be able to generate enough growth for the UK, Germany, and Japan—it is going to have to happen from within.

And that’s a scenario unlike 2008, unlike the 1960s, and in some ways, different from nearly any time since World War II.

Josh Lipsky is the senior director of the Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center and a former adviser to the International Monetary Fund.

Alisha Chhangani is a program assistant for the Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center where she supports the center’s future of money work

This post is adapted from the GeoEconomics Center’s weekly Guide to the Global Economy newsletter. If you are interested in getting the newsletter, email SBusch@atlanticcouncil.org

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.

Further reading

Mon, May 8, 2023

Japan’s monetary trilemma is a warning to the world

Econographics By

High inflation, high levels of debt, and uncertain financial stability - Washington, London, Brussels, Frankfurt and beyond have much to learn from Tokyo's experience.

Wed, Feb 14, 2024

Brazil aims to advance its bid for leadership of the Global South through food security

Econographics By Josh Lipsky, Mrugank Bhusari

If Brazil delivers tangible benefits on food security through its Presidency of the G20 and COP30, it will cement its position as a key leader of the Global South.

Wed, Jan 24, 2024

The advanced consumer economy driving India’s ascent

Econographics By Josh Lipsky, Sophia Busch

By 2030, India could become the world's third-largest economy. Here's how the rise of powerful consumers within the country is creating a massive new domestic and international market.

Image: Lucca, Italy - April 09, 2017: The facade of the Ducal Palace in Lucca with the flags of the nations that take part at the G7 Foreign Affairs Ministers 2017